Siphonophorae

This article includes a list of references, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations. (September 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

| Siphonophorae | |

|---|---|

| |

Portuguese man o' war (Physalia physalis) | |

Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Cnidaria |

| Class: | Hydrozoa |

| Subclass: | Hydroidolina |

| Order: | Siphonophorae Eschscholtz, 1829 |

Synonyms | |

| |

@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinner{width:100%!important;max-width:none!important}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{float:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center}}

Apolemia uvaria[1]

The Siphonophorae or Siphonophora, the siphonophores, are an order of the hydrozoans, a class of marine animals belonging to the phylum Cnidaria. According to the World Register of Marine Species, the order contains 188 species.[2] Although a siphonophore may appear to be a single organism, each specimen is in fact a colonial organism composed of small individual animals called zooids that have their own special function for survival. Most colonies are long, thin, transparent floaters living in the pelagic zone. Some siphonophores, such as the venomous Portuguese man o' war and the Indo-Pacific man o' war, superficially resemble jellyfish.

Another species of siphonophore, Praya dubia, is one of the longest animals in the world, with a body length of 40–50 m (130–160 ft).[3] The term originates from the Greek siphōn "tube" + pherein "to bear".[4]

Contents

1 Description

2 Systematics

3 Haeckel's siphonophores

4 References

5 Further reading

6 External links

Description

Siphonophores are of special scientific interest because they are composed of medusoid and polypoid zooids that are morphologically and functionally specialized. Each zooid is an individual organism, but its integration with others is so strong that the colony attains the function of a larger organism. Indeed, most of the zooids are so specialized, they lack the ability to survive on their own. This is somewhat analogous to the construction and function of multicellular organisms; because multicellular organisms have organs which, like zooids, are specialized and interdependent, siphonophores may provide clues regarding the evolution of more complex bodies.[3]

Like other hydrozoans, certain siphonophores can emit light. A siphonophore of the genus Erenna has been discovered at a depth of around 1,600 m (5,200 ft) off the coast of Monterey, California. The individuals from these colonies are strung together like a feather boa. They prey on small animals using stinging cells. Among the stinging cells are stalks with red glowing ends. The tips twitch back and forth, creating a twinkling effect. Twinkling red lights are thought to attract the small fish eaten by these siphonophores.

While many sea animals produce blue and green bioluminescence, this siphonophore was only the second lifeform found to produce a red light (the first being the scaleless dragonfish Chirostomias pliopterus).[5]

Systematics

Due to their highly specialized colonies, siphonophores have long misled scientists. They were for a long time believed to be a highly distinct group, but now are known to have evolved from simpler colonial hydrozoans similar to those in the orders Anthoathecata and Leptothecata.[6] Consequently, they are now united with these in the subclass Hydroidolina.

The Siphonophorae have long fascinated scientists due to their dramatic appearance, as well as the large size and dangerous sting of several species. Compared to their relatives, their systematics are relatively straightforward:[7]

- Suborder Calycophorae

Abylidae Agassiz, 1862

Clausophyidae Totton, 1965

Diphyidae Quoy & Gaimard, 1827

Hippopodiidae Kölliker, 1853

Prayidae Kölliker, 1853

Sphaeronectidae Huxley, 1859

Tottonophyidae Pugh, Dunn & Haddock, 2018

- Suborder Cystonectae

Physaliidae Brandt, 1835

Rhizophysidae Brandt, 1835

- Suborder Physonectae

Agalmatidae Brandt, 1834

Apolemiidae Huxley, 1859

Cordagalmatidae Pugh, 2016

Erennidae Pugh, 2001

Forskaliidae Haeckel, 1888

Physophoridae Eschscholtz, 1829

Pyrostephidae Moser, 1925

Resomiidae Pugh, 2006

Rhodaliidae Haeckel, 1888

Stephanomiidae Huxley, 1859

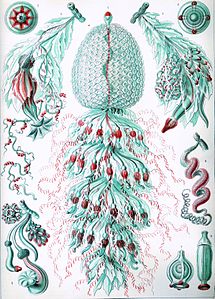

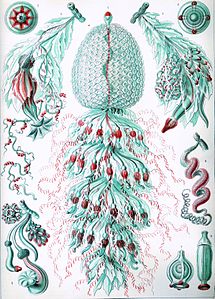

Haeckel's siphonophores

Play media

Play mediaNanomia bijuga

Ernst Haeckel described a number of siphonophores, and several plates from his Kunstformen der Natur (1904) depict members of the taxon:

Plate 7

Plate 37

Plate 59

Plate 77

References

^ Cnidaria – the nettle animals Te Ara, The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Updated: 13 July 2012. Accessed 31 March 2015.

^ Siphonophorae (2018):

Siphonophorae World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

^ ab Dunn, Casey (2005): Siphonophores. Retrieved 2008-JUL-08.

^ Siphonophora Oxford dictionary. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

^ Haddock SH, Dunn CW, Pugh PR, Schnitzler CE (July 2005). "Bioluminescent and red-fluorescent lures in a deep-sea siphonophore". Science. 309 (5732): 263. doi:10.1126/science.1110441. PMID 16002609..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Collins, Allen G. (30 April 2002). "Phylogeny of Medusozoa and the evolution of cnidarian life cycles". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 15 (3): 432. doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2002.00403.x. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

^ MarineSpecies.org (2008): Anthomedusae. Retrieved 2008-JUL-08.

Further reading

Mapstone, Gillian M. (2009). Siphonophora (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa) of Canadian Pacific waters. Ottawa: NRC Research Press. ISBN 978-0-660-19843-9.

- PinkTentacle.com (2008): Siphonophore: Deep-sea superorganism (video). Retrieved 2009-MAY-23.

External links

Dunn, Casey (n.d.). "Siphonophores". Siphonophores. n/a. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

scubamedia.de (30 August 2013). "Tauchen in Norwegen - Kvasefjord". YouTube. scubamedia.de. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

pinktentacle3 (22 December 2008). "Siphonophore". YouTube. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

"Stunning Siphonophore Sighting". Nautilus Live: Explore the ocean LIVE with Dr. Robert Ballard and the Corps of Exploration. Ocean Exploration Trust. 27 June 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

''Deep sea siphonophore'' (10 April 2017) YouTube. Imaged by the NOAA Okeanos Explorer on March 14, 2017 at 1,560 meters west of Winslow Reef complex. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

Comments

Post a Comment