Gamma distribution

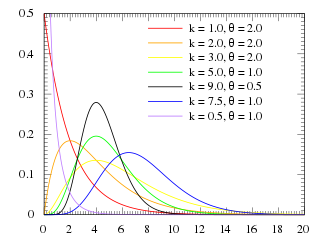

Probability density function | ||

Cumulative distribution function | ||

| Parameters |

|

|

|---|---|---|

Support | x∈(0,∞){displaystyle xin (0,infty )}  | x∈(0,∞){displaystyle xin (0,infty )}  |

1Γ(k)θkxk−1e−xθ{displaystyle {frac {1}{Gamma (k)theta ^{k}}}x^{k-1}e^{-{frac {x}{theta }}}}  | βαΓ(α)xα−1e−βx{displaystyle {frac {beta ^{alpha }}{Gamma (alpha )}}x^{alpha -1}e^{-beta x}}  | |

CDF | 1Γ(k)γ(k,xθ){displaystyle {frac {1}{Gamma (k)}}gamma left(k,{frac {x}{theta }}right)}  | 1Γ(α)γ(α,βx){displaystyle {frac {1}{Gamma (alpha )}}gamma (alpha ,beta x)}  |

Mean | E[X]=kθ{displaystyle operatorname {E} [X]=ktheta } ![{displaystyle operatorname {E} [X]=ktheta }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1de278e52334689991d93625f47897bf0b508601) | E[X]=αβ{displaystyle operatorname {E} [X]={frac {alpha }{beta }}} ![{displaystyle operatorname {E} [X]={frac {alpha }{beta }}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6f99b7dbc2927cef4a361495ba94743c51723c22) |

Median | No simple closed form | No simple closed form |

Mode | (k−1)θ for k≥1{displaystyle (k-1)theta {text{ for }}kgeq 1}  | α−1β for α≥1{displaystyle {frac {alpha -1}{beta }}{text{ for }}alpha geq 1}  |

Variance | Var(X)=kθ2{displaystyle operatorname {Var} (X)=ktheta ^{2}}  | Var(X)=αβ2{displaystyle operatorname {Var} (X)={frac {alpha }{beta ^{2}}}}  |

Skewness | 2k{displaystyle {frac {2}{sqrt {k}}}}  | 2α{displaystyle {frac {2}{sqrt {alpha }}}}  |

| Excess kurtosis | 6k{displaystyle {frac {6}{k}}}  | 6α{displaystyle {frac {6}{alpha }}}  |

Entropy | k+lnθ+lnΓ(k)+(1−k)ψ(k){displaystyle {begin{aligned}k&+ln theta +ln Gamma (k)\&+(1-k)psi (k)end{aligned}}}  | α−lnβ+lnΓ(α)+(1−α)ψ(α){displaystyle {begin{aligned}alpha &-ln beta +ln Gamma (alpha )\&+(1-alpha )psi (alpha )end{aligned}}}  |

MGF | (1−θt)−k for t<1θ{displaystyle (1-theta t)^{-k}{text{ for }}t<{frac {1}{theta }}}  | (1−tβ)−α for t<β{displaystyle left(1-{frac {t}{beta }}right)^{-alpha }{text{ for }}t<beta }  |

CF | (1−θit)−k{displaystyle (1-theta it)^{-k}}  | (1−itβ)−α{displaystyle left(1-{frac {it}{beta }}right)^{-alpha }}  |

In probability theory and statistics, the gamma distribution is a two-parameter family of continuous probability distributions. The exponential distribution, Erlang distribution, and chi-squared distribution are special cases of the gamma distribution. There are three different parametrizations in common use:

- With a shape parameter k and a scale parameter θ.

- With a shape parameter α = k and an inverse scale parameter β = 1/θ, called a rate parameter.

- With a shape parameter k and a mean parameter μ = kθ = α/β.

In each of these three forms, both parameters are positive real numbers.

The gamma distribution is the maximum entropy probability distribution (both with respect to a uniform base measure and with respect to a 1/x base measure) for a random variable X for which E[X] = kθ = α/β is fixed and greater than zero, and E[ln(X)] = ψ(k) + ln(θ) = ψ(α) − ln(β) is fixed (ψ is the digamma function).[1]

Contents

1 Parameterizations

1.1 Characterization using shape α and rate β

1.2 Characterization using shape k and scale θ

2 Properties

2.1 Skewness

2.2 Median calculation

2.3 Summation

2.4 Scaling

2.5 Exponential family

2.6 Logarithmic expectation and variance

2.7 Information entropy

2.8 Kullback–Leibler divergence

2.9 Laplace transform

3 Parameter estimation

3.1 Maximum likelihood estimation

3.2 Bayesian minimum mean squared error

4 Generating gamma-distributed random variables

5 Applications

6 Related distributions

6.1 Special cases

6.2 Conjugate prior

6.3 Compound gamma

7 Related distributions and properties

8 Notes

9 References

10 External links

Parameterizations

The parameterization with k and θ appears to be more common in econometrics and certain other applied fields, where for example the gamma distribution is frequently used to model waiting times. For instance, in life testing, the waiting time until death is a random variable that is frequently modeled with a gamma distribution.[2]

The parameterization with α and β is more common in Bayesian statistics, where the gamma distribution is used as a conjugate prior distribution for various types of inverse scale (aka rate) parameters, such as the λ of an exponential distribution or a Poisson distribution[3] – or for that matter, the β of the gamma distribution itself. (The closely related inverse gamma distribution is used as a conjugate prior for scale parameters, such as the variance of a normal distribution.)

If k is a positive integer, then the distribution represents an Erlang distribution; i.e., the sum of k independent exponentially distributed random variables, each of which has a mean of θ.

Characterization using shape α and rate β

The gamma distribution can be parameterized in terms of a shape parameter α = k and an inverse scale parameter β = 1/θ, called a rate parameter. A random variable X that is gamma-distributed with shape α and rate β is denoted

- X∼Γ(α,β)≡Gamma(α,β){displaystyle Xsim Gamma (alpha ,beta )equiv operatorname {Gamma} (alpha ,beta )}

The corresponding probability density function in the shape-rate parametrization is

- f(x;α,β)=βαxα−1e−βxΓ(α) for x>0 and α,β>0,{displaystyle f(x;alpha ,beta )={frac {beta ^{alpha }x^{alpha -1}e^{-beta x}}{Gamma (alpha )}}quad {text{ for }}x>0{text{ and }}alpha ,beta >0,}

where Γ(α){displaystyle Gamma (alpha )}

Both parametrizations are common because either can be more convenient depending on the situation.

The cumulative distribution function is the regularized gamma function:

- F(x;α,β)=∫0xf(u;α,β)du=γ(α,βx)Γ(α),{displaystyle F(x;alpha ,beta )=int _{0}^{x}f(u;alpha ,beta ),du={frac {gamma (alpha ,beta x)}{Gamma (alpha )}},}

where γ(α,βx){displaystyle gamma (alpha ,beta x)}

If α is a positive integer (i.e., the distribution is an Erlang distribution), the cumulative distribution function has the following series expansion:[4]

- F(x;α,β)=1−∑i=0α−1(βx)ii!e−βx=e−βx∑i=α∞(βx)ii!.{displaystyle F(x;alpha ,beta )=1-sum _{i=0}^{alpha -1}{frac {(beta x)^{i}}{i!}}e^{-beta x}=e^{-beta x}sum _{i=alpha }^{infty }{frac {(beta x)^{i}}{i!}}.}

Characterization using shape k and scale θ

A random variable X that is gamma-distributed with shape k and scale θ is denoted by

- X∼Γ(k,θ)≡Gamma(k,θ){displaystyle Xsim Gamma (k,theta )equiv operatorname {Gamma} (k,theta )}

Illustration of the gamma PDF for parameter values over k and x with θ set to 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6. One can see each θ layer by itself here [2] as well as by k [3] and x. [4].

The probability density function using the shape-scale parametrization is

- f(x;k,θ)=xk−1e−xθθkΓ(k) for x>0 and k,θ>0.{displaystyle f(x;k,theta )={frac {x^{k-1}e^{-{frac {x}{theta }}}}{theta ^{k}Gamma (k)}}quad {text{ for }}x>0{text{ and }}k,theta >0.}

Here Γ(k) is the gamma function evaluated at k.

The cumulative distribution function is the regularized gamma function:

- F(x;k,θ)=∫0xf(u;k,θ)du=γ(k,xθ)Γ(k),{displaystyle F(x;k,theta )=int _{0}^{x}f(u;k,theta ),du={frac {gamma left(k,{frac {x}{theta }}right)}{Gamma (k)}},}

where γ(k,xθ){displaystyle gamma left(k,{frac {x}{theta }}right)}

It can also be expressed as follows, if k is a positive integer (i.e., the distribution is an Erlang distribution):[4]

- F(x;k,θ)=1−∑i=0k−11i!(xθ)ie−x/θ=e−x/θ∑i=k∞1i!(xθ)i.{displaystyle F(x;k,theta )=1-sum _{i=0}^{k-1}{frac {1}{i!}}left({frac {x}{theta }}right)^{i}e^{-x/theta }=e^{-x/theta }sum _{i=k}^{infty }{frac {1}{i!}}left({frac {x}{theta }}right)^{i}.}

Properties

Skewness

The skewness of the gamma distribution only depends on its shape parameter, k, and it is equal to 2/k.{displaystyle 2/{sqrt {k}}.}

Median calculation

Unlike the mode and the mean which have readily calculable formulas based on the parameters, the median does not have an easy closed form equation. The median for this distribution is defined as the value ν such that

- 1Γ(k)θk∫0νxk−1e−x/θdx=12.{displaystyle {frac {1}{Gamma (k)theta ^{k}}}int _{0}^{nu }x^{k-1}e^{-x/theta }dx={frac {1}{2}}.}

A formula for approximating the median for any gamma distribution, when the mean is known, has been derived based on the fact that the ratio μ/(μ − ν) is approximately a linear function of k when k ≥ 1.[5] The approximation formula is

- ν≈μ3k−0.83k+0.2,{displaystyle nu approx mu {frac {3k-0.8}{3k+0.2}},}

where μ=kθ{displaystyle mu =ktheta }

A rigorous treatment of the problem of determining an asymptotic expansion and bounds for the median of the Gamma Distribution was handled first by Chen and Rubin, who proved

- m−13<λ(m)<m,{displaystyle m-{frac {1}{3}}<lambda (m)<m,}

where λ(m){displaystyle lambda (m)}

K. P. Choi later showed that the first five terms in the asymptotic expansion of the median are

- λ(m)=m−13+8405m+18425515m2+22483444525m3−⋯{displaystyle lambda (m)=m-{frac {1}{3}}+{frac {8}{405m}}+{frac {184}{25515m^{2}}}+{frac {2248}{3444525m^{3}}}-cdots }

by comparing the median to Ramanujan's θ{displaystyle theta }

Later, it was shown that λ(m){displaystyle lambda (m)}

Summation

If Xi has a Gamma(ki, θ) distribution for i = 1, 2, ..., N (i.e., all distributions have the same scale parameter θ), then

- ∑i=1NXi∼Gamma(∑i=1Nki,θ){displaystyle sum _{i=1}^{N}X_{i}sim mathrm {Gamma} left(sum _{i=1}^{N}k_{i},theta right)}

provided all Xi are independent.

For the cases where the Xi are independent but have different scale parameters see Mathai (1982) and Moschopoulos (1984).

The gamma distribution exhibits infinite divisibility.

Scaling

If

- X∼Gamma(k,θ),{displaystyle Xsim mathrm {Gamma} (k,theta ),}

then, for any c > 0,

cX∼Gamma(k,cθ),{displaystyle cXsim mathrm {Gamma} (k,c,theta ),}by moment generating functions,

or equivalently

- cX∼Gamma(α,βc),{displaystyle cXsim mathrm {Gamma} left(alpha ,{frac {beta }{c}}right),}

Indeed, we know that if X is an exponential r.v. with rate λ then cX is an exponential r.v. with rate λ/c; the same thing is valid with Gamma variates (and this can be checked using the moment-generating function, see, e.g.,these notes, 10.4-(ii)): multiplication by a positive constant c divides the rate (or, equivalently, multiplies the scale).

Exponential family

The gamma distribution is a two-parameter exponential family with natural parameters k − 1 and −1/θ (equivalently, α − 1 and −β), and natural statistics X and ln(X).

If the shape parameter k is held fixed, the resulting one-parameter family of distributions is a natural exponential family.

Logarithmic expectation and variance

One can show that

- E[ln(X)]=ψ(α)−ln(β){displaystyle operatorname {E} [ln(X)]=psi (alpha )-ln(beta )}

or equivalently,

- E[ln(X)]=ψ(k)+ln(θ){displaystyle operatorname {E} [ln(X)]=psi (k)+ln(theta )}

where ψ is the digamma function. Likewise,

- var[ln(X)]=ψ(1)(α)=ψ(1)(k){displaystyle operatorname {var} [ln(X)]=psi ^{(1)}(alpha )=psi ^{(1)}(k)}

where ψ(1){displaystyle psi ^{(1)}}

This can be derived using the exponential family formula for the moment generating function of the sufficient statistic, because one of the sufficient statistics of the gamma distribution is ln(x).

Information entropy

The information entropy is

- H(X)=E[−ln(p(X))]=E[−αln(β)+ln(Γ(α))−(α−1)ln(X)+βX]=α−ln(β)+ln(Γ(α))+(1−α)ψ(α).{displaystyle {begin{aligned}operatorname {H} (X)&=operatorname {E} [-ln(p(X))]\&=operatorname {E} [-alpha ln(beta )+ln(Gamma (alpha ))-(alpha -1)ln(X)+beta X]\&=alpha -ln(beta )+ln(Gamma (alpha ))+(1-alpha )psi (alpha ).end{aligned}}}

In the k, θ parameterization, the information entropy is given by

- H(X)=k+ln(θ)+ln(Γ(k))+(1−k)ψ(k).{displaystyle operatorname {H} (X)=k+ln(theta )+ln(Gamma (k))+(1-k)psi (k).}

Kullback–Leibler divergence

Illustration of the Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence for two gamma PDFs. Here β = β0 + 1 which are set to 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6. The typical asymmetry for the KL divergence is clearly visible.

The Kullback–Leibler divergence (KL-divergence), of Gamma(αp, βp) ("true" distribution) from Gamma(αq, βq) ("approximating" distribution) is given by[9]

- DKL(αp,βp;αq,βq)=(αp−αq)ψ(αp)−logΓ(αp)+logΓ(αq)+αq(logβp−logβq)+αpβq−βpβp.{displaystyle {begin{aligned}D_{mathrm {KL} }(alpha _{p},beta _{p};alpha _{q},beta _{q})={}&(alpha _{p}-alpha _{q})psi (alpha _{p})-log Gamma (alpha _{p})+log Gamma (alpha _{q})\&{}+alpha _{q}(log beta _{p}-log beta _{q})+alpha _{p}{frac {beta _{q}-beta _{p}}{beta _{p}}}.end{aligned}}}

Written using the k, θ parameterization, the KL-divergence of Gamma(kp, θp) from Gamma(kq, θq) is given by

- DKL(kp,θp;kq,θq)=(kp−kq)ψ(kp)−logΓ(kp)+logΓ(kq)+kq(logθq−logθp)+kpθp−θqθq.{displaystyle {begin{aligned}D_{mathrm {KL} }(k_{p},theta _{p};k_{q},theta _{q})={}&(k_{p}-k_{q})psi (k_{p})-log Gamma (k_{p})+log Gamma (k_{q})\&{}+k_{q}(log theta _{q}-log theta _{p})+k_{p}{frac {theta _{p}-theta _{q}}{theta _{q}}}.end{aligned}}}

Laplace transform

The Laplace transform of the gamma PDF is

- F(s)=(1+θs)−k=βα(s+β)α.{displaystyle F(s)=(1+theta s)^{-k}={frac {beta ^{alpha }}{(s+beta )^{alpha }}}.}

Parameter estimation

Maximum likelihood estimation

The likelihood function for N iid observations (x1, ..., xN) is

- L(k,θ)=∏i=1Nf(xi;k,θ){displaystyle L(k,theta )=prod _{i=1}^{N}f(x_{i};k,theta )}

from which we calculate the log-likelihood function

- ℓ(k,θ)=(k−1)∑i=1Nln(xi)−∑i=1Nxiθ−Nkln(θ)−Nln(Γ(k)){displaystyle ell (k,theta )=(k-1)sum _{i=1}^{N}ln {(x_{i})}-sum _{i=1}^{N}{frac {x_{i}}{theta }}-Nkln(theta )-Nln(Gamma (k))}

Finding the maximum with respect to θ by taking the derivative and setting it equal to zero yields the maximum likelihood estimator of the θ parameter:

- θ^=1kN∑i=1Nxi{displaystyle {hat {theta }}={frac {1}{kN}}sum _{i=1}^{N}x_{i}}

Substituting this into the log-likelihood function gives

- ℓ=(k−1)∑i=1Nln(xi)−Nk−Nkln(∑xikN)−Nln(Γ(k)){displaystyle ell =(k-1)sum _{i=1}^{N}ln {(x_{i})}-Nk-Nkln {left({frac {sum x_{i}}{kN}}right)}-Nln(Gamma (k))}

Finding the maximum with respect to k by taking the derivative and setting it equal to zero yields

- ln(k)−ψ(k)=ln(1N∑i=1Nxi)−1N∑i=1Nln(xi){displaystyle ln(k)-psi (k)=ln left({frac {1}{N}}sum _{i=1}^{N}x_{i}right)-{frac {1}{N}}sum _{i=1}^{N}ln(x_{i})}

There is no closed-form solution for k. The function is numerically very well behaved, so if a numerical solution is desired, it can be found using, for example, Newton's method. An initial value of k can be found either using the method of moments, or using the approximation

- ln(k)−ψ(k)≈12k(1+16k+1){displaystyle ln(k)-psi (k)approx {frac {1}{2k}}left(1+{frac {1}{6k+1}}right)}

If we let

- s=ln(1N∑i=1Nxi)−1N∑i=1Nln(xi){displaystyle s=ln left({frac {1}{N}}sum _{i=1}^{N}x_{i}right)-{frac {1}{N}}sum _{i=1}^{N}ln(x_{i})}

then k is approximately

- k≈3−s+(s−3)2+24s12s{displaystyle kapprox {frac {3-s+{sqrt {(s-3)^{2}+24s}}}{12s}}}

which is within 1.5% of the correct value.[10] An explicit form for the Newton–Raphson update of this initial guess is:[11]

- k←k−ln(k)−ψ(k)−s1k−ψ′(k).{displaystyle kleftarrow k-{frac {ln(k)-psi (k)-s}{{frac {1}{k}}-psi ^{prime }(k)}}.}

Bayesian minimum mean squared error

With known k and unknown θ, the posterior density function for theta (using the standard scale-invariant prior for θ) is

- P(θ∣k,x1,…,xN)∝1θ∏i=1Nf(xi;k,θ){displaystyle P(theta mid k,x_{1},dots ,x_{N})propto {frac {1}{theta }}prod _{i=1}^{N}f(x_{i};k,theta )}

Denoting

- y≡∑i=1Nxi,P(θ∣k,x1,…,xN)=C(xi)θ−Nk−1e−y/θ{displaystyle yequiv sum _{i=1}^{N}x_{i},qquad P(theta mid k,x_{1},dots ,x_{N})=C(x_{i})theta ^{-Nk-1}e^{-y/theta }}

Integration with respect to θ can be carried out using a change of variables, revealing that 1/θ is gamma-distributed with parameters α = Nk, β = y.

- ∫0∞θ−Nk−1+me−y/θdθ=∫0∞xNk−1−me−xydx=y−(Nk−m)Γ(Nk−m){displaystyle int _{0}^{infty }theta ^{-Nk-1+m}e^{-y/theta },dtheta =int _{0}^{infty }x^{Nk-1-m}e^{-xy},dx=y^{-(Nk-m)}Gamma (Nk-m)!}

The moments can be computed by taking the ratio (m by m = 0)

- E[xm]=Γ(Nk−m)Γ(Nk)ym{displaystyle operatorname {E} [x^{m}]={frac {Gamma (Nk-m)}{Gamma (Nk)}}y^{m}}

which shows that the mean ± standard deviation estimate of the posterior distribution for θ is

- yNk−1±y2(Nk−1)2(Nk−2).{displaystyle {frac {y}{Nk-1}}pm {frac {y^{2}}{(Nk-1)^{2}(Nk-2)}}.}

Generating gamma-distributed random variables

Given the scaling property above, it is enough to generate gamma variables with θ = 1 as we can later convert to any value of β with simple division.

Suppose we wish to generate random variables from Gamma(n + δ, 1), where n is a non-negative integer and 0 < δ < 1. Using the fact that a Gamma(1, 1) distribution is the same as an Exp(1) distribution, and noting the method of generating exponential variables, we conclude that if U is uniformly distributed on (0, 1], then −ln(U) is distributed Gamma(1, 1). Now, using the "α-addition" property of gamma distribution, we expand this result:

- −∑k=1nlnUk∼Γ(n,1){displaystyle -sum _{k=1}^{n}ln U_{k}sim Gamma (n,1)}

where Uk are all uniformly distributed on (0, 1] and independent. All that is left now is to generate a variable distributed as Gamma(δ, 1) for 0 < δ < 1 and apply the "α-addition" property once more. This is the most difficult part.

Random generation of gamma variates is discussed in detail by Devroye,[12]:401–428 noting that none are uniformly fast for all shape parameters. For small values of the shape parameter, the algorithms are often not valid.[12]:406 For arbitrary values of the shape parameter, one can apply the Ahrens and Dieter[13] modified acceptance–rejection method Algorithm GD (shape k ≥ 1), or transformation method[14] when 0 < k < 1. Also see Cheng and Feast Algorithm GKM 3[15] or Marsaglia's squeeze method.[16]

The following is a version of the Ahrens-Dieter acceptance–rejection method:[13]

- Generate U, V and W as iid uniform (0, 1] variates.

- If U≤ee+δ{displaystyle Uleq {frac {e}{e+delta }}}

then ξ=V1/δ{displaystyle xi =V^{1/delta }}

and η=Wξδ−1{displaystyle eta =Wxi ^{delta -1}}

. Otherwise, ξ=1−lnV{displaystyle xi =1-ln V}

and η=We−ξ{displaystyle eta =We^{-xi }}

.

- If η>ξδ−1e−ξ{displaystyle eta >xi ^{delta -1}e^{-xi }}

then go to step 1.

- ξ is distributed as Γ(δ, 1).

A summary of this is

- θ(ξ−∑i=1⌊k⌋ln(Ui))∼Γ(k,θ){displaystyle theta left(xi -sum _{i=1}^{lfloor krfloor }ln(U_{i})right)sim Gamma (k,theta )}

where ⌊k⌋{displaystyle scriptstyle lfloor krfloor }

While the above approach is technically correct, Devroye notes that it is linear in the value of k and in general is not a good choice. Instead he recommends using either rejection-based or table-based methods, depending on context.[12]:401–428

For example, Marsaglia's simple transformation-rejection method relying on a one normal and one uniform random number:[17]

- Setup: d = a - 1/3, c = 1/sqrt(9d).

- Generate: v=(1+c*x)ˆ3, with x standard normal.

- if v > 0 and log(UNI) < 0.5 · xˆ2 + d − dv + d log(v) return dv.

- go back to step 2.

With 1≤a=α=k{displaystyle 1leq a=alpha =k}

Applications

The gamma distribution has been used to model the size of insurance claims[18] and rainfalls.[19] This means that aggregate insurance claims and the amount of rainfall accumulated in a reservoir are modelled by a gamma process – much like the exponential distribution generates a Poisson process.

The gamma distribution is also used to model errors in multi-level Poisson regression models, because the combination of the Poisson distribution and a gamma distribution is a negative binomial distribution.[clarification needed]

In wireless communication, the gamma distribution is used to model the multi-path fading of signal power.

In oncology, the age distribution of cancer incidence often follows the gamma distribution, whereas the shape and scale parameters predict, respectively, the number of driver events and the time interval between them [20].

In neuroscience, the gamma distribution is often used to describe the distribution of inter-spike intervals.[21][22]

In bacterial gene expression, the copy number of a constitutively expressed protein often follows the gamma distribution, where the scale and shape parameter are, respectively, the mean number of bursts per cell cycle and the mean number of protein molecules produced by a single mRNA during its lifetime.[23]

In genomics, the gamma distribution was applied in peak calling step (i.e. in recognition of signal) in ChIP-chip[24] and ChIP-seq[25] data analysis.

The gamma distribution is widely used as a conjugate prior in Bayesian statistics. It is the conjugate prior for the precision (i.e. inverse of the variance) of a normal distribution. It is also the conjugate prior for the exponential distribution.

Related distributions

Special cases

Conjugate prior

In Bayesian inference, the gamma distribution is the conjugate prior to many likelihood distributions: the Poisson, exponential, normal (with known mean), Pareto, gamma with known shape σ, inverse gamma with known shape parameter, and Gompertz with known scale parameter.

The gamma distribution's conjugate prior is:[26]

- p(k,θ∣p,q,r,s)=1Zpk−1e−θ−1qΓ(k)rθks,{displaystyle p(k,theta mid p,q,r,s)={frac {1}{Z}}{frac {p^{k-1}e^{-theta ^{-1}q}}{Gamma (k)^{r}theta ^{ks}}},}

where Z is the normalizing constant, which has no closed-form solution.

The posterior distribution can be found by updating the parameters as follows:

- p′=p∏ixi,q′=q+∑ixi,r′=r+n,s′=s+n,{displaystyle {begin{aligned}p'&=pprod nolimits _{i}x_{i},\q'&=q+sum nolimits _{i}x_{i},\r'&=r+n,\s'&=s+n,end{aligned}}}

where n is the number of observations, and xi is the ith observation.

Compound gamma

If the shape parameter of the gamma distribution is known, but the inverse-scale parameter is unknown, then a gamma distribution for the inverse-scale forms a conjugate prior. The compound distribution, which results from integrating out the inverse-scale, has a closed form solution, known as the compound gamma distribution.[27]

If instead the shape parameter is known but the mean is unknown, with the prior of the mean being given by another gamma distribution, then it results in K-distribution.

Related distributions and properties

- If X ~ Gamma(1, 1/λ) (shape -scale parametrization), then X has an exponential distribution with rate parameter λ.

- If X ~ Gamma(ν/2, 2)(shape -scale parametrization), then X is identical to χ2(ν), the chi-squared distribution with ν degrees of freedom. Conversely, if Q ~ χ2(ν) and c is a positive constant, then cQ ~ Gamma(ν/2, 2c).

- If k is an integer, the gamma distribution is an Erlang distribution and is the probability distribution of the waiting time until the kth "arrival" in a one-dimensional Poisson process with intensity 1/θ. If

- X∼Γ(k∈Z,θ),Y∼Pois(xθ),{displaystyle Xsim Gamma (kin mathbf {Z} ,theta ),qquad Ysim mathrm {Pois} left({frac {x}{theta }}right),}

- X∼Γ(k∈Z,θ),Y∼Pois(xθ),{displaystyle Xsim Gamma (kin mathbf {Z} ,theta ),qquad Ysim mathrm {Pois} left({frac {x}{theta }}right),}

- then

- P(X>x)=P(Y<k).{displaystyle P(X>x)=P(Y<k).}

- P(X>x)=P(Y<k).{displaystyle P(X>x)=P(Y<k).}

- If X has a Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution with parameter a, then

X2∼Γ(32,2a2){displaystyle X^{2}sim Gamma left({tfrac {3}{2}},2a^{2}right)}.

- If X ~ Gamma(k, θ), then X{displaystyle {sqrt {X}}}

follows a generalized gamma distribution with parameters p = 2, d = 2k, and a=θ{displaystyle a={sqrt {theta }}}

[citation needed].

- More generally, if X ~ Gamma(k,θ), then Xq{displaystyle X^{q}}

for q>0{displaystyle q>0}

follows a generalized gamma distribution with parameters p = 1/q, d = k/q, and a=θq{displaystyle a=theta ^{q}}

.

- If X ~ Gamma(k, θ), then 1/X ~ Inv-Gamma(k, θ−1) (see Inverse-gamma distribution for derivation).

- Parametrization 1: If Xk∼Γ(αk,θk){displaystyle X_{k}sim Gamma (alpha _{k},theta _{k}),}

are independent, then α2θ2X1α1θ1X2∼F(2α1,2α2){displaystyle {frac {alpha _{2}theta _{2}X_{1}}{alpha _{1}theta _{1}X_{2}}}sim mathrm {F} (2alpha _{1},2alpha _{2})}

, or equivalently, X1X2∼β′(α1,α2,1,θ1θ2){displaystyle {frac {X_{1}}{X_{2}}}sim beta ^{'}(alpha _{1},alpha _{2},1,{frac {theta _{1}}{theta _{2}}})}

- Parametrization 2: If Xk∼Γ(αk,βk){displaystyle X_{k}sim Gamma (alpha _{k},beta _{k}),}

are independent, then α2β1X1α1β2X2∼F(2α1,2α2){displaystyle {frac {alpha _{2}beta _{1}X_{1}}{alpha _{1}beta _{2}X_{2}}}sim mathrm {F} (2alpha _{1},2alpha _{2})}

, or equivalently, X1X2∼β′(α1,α2,1,β2β1){displaystyle {frac {X_{1}}{X_{2}}}sim beta ^{'}(alpha _{1},alpha _{2},1,{frac {beta _{2}}{beta _{1}}})}

- If X ~ Gamma(α, θ) and Y ~ Gamma(β, θ) are independently distributed, then X/(X + Y) has a beta distribution with parameters α and β, and X/(X + Y) is independent of X + Y, which is Gamma(α + β, θ)-distributed.

- If Xi ~ Gamma(αi, 1) are independently distributed, then the vector (X1/S, ..., Xn/S), where S = X1 + ... + Xn, follows a Dirichlet distribution with parameters α1, ..., αn.

- For large k the gamma distribution converges to normal distribution with mean μ = kθ and variance σ2 = kθ2.

- The gamma distribution is the conjugate prior for the precision of the normal distribution with known mean.

- The Wishart distribution is a multivariate generalization of the gamma distribution (samples are positive-definite matrices rather than positive real numbers).

- The gamma distribution is a special case of the generalized gamma distribution, the generalized integer gamma distribution, and the generalized inverse Gaussian distribution.

- Among the discrete distributions, the negative binomial distribution is sometimes considered the discrete analogue of the Gamma distribution.

Tweedie distributions – the gamma distribution is a member of the family of Tweedie exponential dispersion models.

Notes

^ Park, Sung Y.; Bera, Anil K. (2009). "Maximum entropy autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity model" (PDF). Journal of Econometrics. Elsevier: 219–230. doi:10.1016/j.jeconom.2008.12.014. Retrieved 2011-06-02..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ See Hogg and Craig (2005, Remark 3.3.1) for an explicit motivation

^ Scalable Recommendation with Poisson Factorization, Prem Gopalan, Jake M. Hofman, David Blei, arXiv.org 2014

^ ab Papoulis, Pillai, Probability, Random Variables, and Stochastic Processes, Fourth Edition

^ Banneheka BMSG, Ekanayake GEMUPD (2009) "A new point estimator for the median of gamma distribution". Viyodaya J Science, 14:95–103

^ Jeesen Chen, Herman Rubin, Bounds for the difference between median and mean of gamma and poisson distributions, Statistics & Probability Letters, Volume 4, Issue 6, October 1986, Pages 281-283,

ISSN 0167-7152, [1].

^ Choi, K.P. "On the Medians of the Gamma Distributions and an Equation of Ramanujan", Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society, Vol. 121, No. 1 (May, 1994), pp. 245–251.

^ Berg, Christian and Pedersen, Henrik L. "Convexity of the median in the gamma distribution".

^ W.D. Penny, [www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/~wpenny/publications/densities.ps KL-Divergences of Normal, Gamma, Dirichlet, and Wishart densities][full citation needed]

^ Minka, Thomas P. (2002). "Estimating a Gamma distribution" (PDF).

^ Choi, S. C.; Wette, R. (1969). "Maximum Likelihood Estimation of the Parameters of the Gamma Distribution and Their Bias". Technometrics. 11 (4): 683–690. doi:10.1080/00401706.1969.10490731.

^ abc Devroye, Luc (1986). Non-Uniform Random Variate Generation. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-96305-7. See Chapter 9, Section 3.

^ ab Ahrens, J. H.; Dieter, U (January 1982). "Generating gamma variates by a modified rejection technique". Communications of the ACM. 25 (1): 47–54. doi:10.1145/358315.358390.. See Algorithm GD, p. 53.

^ Ahrens, J. H.; Dieter, U. (1974). "Computer methods for sampling from gamma, beta, Poisson and binomial distributions". Computing. 12: 223–246. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.93.3828. doi:10.1007/BF02293108.

^ Cheng, R.C.H., and Feast, G.M. Some simple gamma variate generators. Appl. Stat. 28 (1979), 290–295.

^ Marsaglia, G. The squeeze method for generating gamma variates. Comput, Math. Appl. 3 (1977), 321–325.

^ Marsaglia, G.; Tsang, W. W. (2000). "A simple method for generating gamma variables". ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software. 26 (3): 363–372. doi:10.1145/358407.358414.

^ p. 43, Philip J. Boland, Statistical and Probabilistic Methods in Actuarial Science, Chapman & Hall CRC 2007

^ Aksoy, H. (2000) "Use of Gamma Distribution in Hydrological Analysis", Turk J. Engin Environ Sci, 24, 419 – 428.

^ Belikov, Aleksey V. (22 September 2017). "The number of key carcinogenic events can be predicted from cancer incidence". Scientific Reports. 7 (1). doi:10.1038/s41598-017-12448-7.

^ J. G. Robson and J. B. Troy, "Nature of the maintained discharge of Q, X, and Y retinal ganglion cells of the cat", J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 4, 2301–2307 (1987)

^ M.C.M. Wright, I.M. Winter, J.J. Forster, S. Bleeck "Response to best-frequency tone bursts in the ventral cochlear nucleus is governed by ordered inter-spike interval statistics", Hearing Research 317 (2014)

^ N. Friedman, L. Cai and X. S. Xie (2006) "Linking stochastic dynamics to population distribution: An analytical framework of gene expression", Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 168302.

^ DJ Reiss, MT Facciotti and NS Baliga (2008) "Model-based deconvolution of genome-wide DNA binding", Bioinformatics, 24, 396–403

^ MA Mendoza-Parra, M Nowicka, W Van Gool, H Gronemeyer (2013) "Characterising ChIP-seq binding patterns by model-based peak shape deconvolution", BMC Genomics, 14:834

^ Fink, D. 1995 A Compendium of Conjugate Priors. In progress report: Extension and enhancement of methods for setting data quality objectives. (DOE contract 95‑831).

^ Dubey, Satya D. (December 1970). "Compound gamma, beta and F distributions". Metrika. 16: 27–31. doi:10.1007/BF02613934.

References

R. V. Hogg and A. T. Craig (1978) Introduction to Mathematical Statistics, 4th edition. New York: Macmillan. (See Section 3.3.)'- P. G. Moschopoulos (1985) The distribution of the sum of independent gamma random variables, Annals of the Institute of Statistical Mathematics, 37, 541–544

- A. M. Mathai (1982) Storage capacity of a dam with gamma type inputs, Annals of the Institute of Statistical Mathematics, 34, 591–597

External links

| The Wikibook Statistics has a page on the topic of: Gamma distribution |

Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001) [1994], "Gamma-distribution", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Gamma distribution". MathWorld.

- ModelAssist (2017) Uses of the Gamma distribution in risk modeling, including applied examples in Excel.

- Engineering Statistics Handbook

![{displaystyle operatorname {E} [ln(X)]=psi (alpha )-ln(beta )}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6da14ff7ed563c7e86154998ef6fd180e79c9bfa)

![{displaystyle operatorname {E} [ln(X)]=psi (k)+ln(theta )}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/186737f3b184bf00519b3a4b1412a560e1216093)

![{displaystyle operatorname {var} [ln(X)]=psi ^{(1)}(alpha )=psi ^{(1)}(k)}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b193ce127d5d0de9a3430b7dc803c092262f7b5c)

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}operatorname {H} (X)&=operatorname {E} [-ln(p(X))]\&=operatorname {E} [-alpha ln(beta )+ln(Gamma (alpha ))-(alpha -1)ln(X)+beta X]\&=alpha -ln(beta )+ln(Gamma (alpha ))+(1-alpha )psi (alpha ).end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/aa6206e45a83fd2e7c91253f46e7b4c7923cd0f9)

![{displaystyle operatorname {E} [x^{m}]={frac {Gamma (Nk-m)}{Gamma (Nk)}}y^{m}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/61ae01ae77aa6c640cbaa1bb2a8863454827916a)

Comments

Post a Comment