Dirichlet distribution

Probability density function  | |

| Parameters | K≥2{displaystyle Kgeq 2}  number of categories (integer) number of categories (integer)α1,…,αK{displaystyle alpha _{1},ldots ,alpha _{K}}  concentration parameters, where αi>0{displaystyle alpha _{i}>0} concentration parameters, where αi>0{displaystyle alpha _{i}>0} |

|---|---|

| Support | x1,…,xK{displaystyle x_{1},ldots ,x_{K}}  where xi∈(0,1){displaystyle x_{i}in (0,1)} where xi∈(0,1){displaystyle x_{i}in (0,1)} and ∑i=1Kxi=1{displaystyle sum _{i=1}^{K}x_{i}=1} and ∑i=1Kxi=1{displaystyle sum _{i=1}^{K}x_{i}=1} |

1B(α)∏i=1Kxiαi−1{displaystyle {frac {1}{mathrm {B} ({boldsymbol {alpha }})}}prod _{i=1}^{K}x_{i}^{alpha _{i}-1}}  where B(α)=∏i=1KΓ(αi)Γ(∑i=1Kαi){displaystyle mathrm {B} ({boldsymbol {alpha }})={frac {prod _{i=1}^{K}Gamma (alpha _{i})}{Gamma {bigl (}sum _{i=1}^{K}alpha _{i}{bigr )}}}}  where α=(α1,…,αK){displaystyle {boldsymbol {alpha }}=(alpha _{1},ldots ,alpha _{K})}  | |

| Mean | E[Xi]=αi∑kαk{displaystyle operatorname {E} [X_{i}]={frac {alpha _{i}}{sum _{k}alpha _{k}}}} ![operatorname {E} [X_{i}]={frac {alpha _{i}}{sum _{k}alpha _{k}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fba3f45d2d1945a428884b57067ac66a7481ad10) E[lnXi]=ψ(αi)−ψ(∑kαk){displaystyle operatorname {E} [ln X_{i}]=psi (alpha _{i})-psi (textstyle sum _{k}alpha _{k})} ![operatorname {E} [ln X_{i}]=psi (alpha _{i})-psi (textstyle sum _{k}alpha _{k})](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/af11020481980cb1aa891045a0f07ebb172ccd3d) (see digamma function) |

| Mode | xi=αi−1∑k=1Kαk−K,αi>1.{displaystyle x_{i}={frac {alpha _{i}-1}{sum _{k=1}^{K}alpha _{k}-K}},quad alpha _{i}>1.} |

| Variance | Var[Xi]=αi(α0−αi)α02(α0+1),{displaystyle operatorname {Var} [X_{i}]={frac {alpha _{i}(alpha _{0}-alpha _{i})}{alpha _{0}^{2}(alpha _{0}+1)}},} ![{displaystyle operatorname {Var} [X_{i}]={frac {alpha _{i}(alpha _{0}-alpha _{i})}{alpha _{0}^{2}(alpha _{0}+1)}},}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2d43f3f3ff4d55f4230f421123324cb1d74b921e) where α0=∑i=1Kαi{displaystyle alpha _{0}=sum _{i=1}^{K}alpha _{i}}  Cov[Xi,Xj]=−αiαjα02(α0+1) (i≠j){displaystyle operatorname {Cov} [X_{i},X_{j}]={frac {-alpha _{i}alpha _{j}}{alpha _{0}^{2}(alpha _{0}+1)}}~~(ineq j)} ![{displaystyle operatorname {Cov} [X_{i},X_{j}]={frac {-alpha _{i}alpha _{j}}{alpha _{0}^{2}(alpha _{0}+1)}}~~(ineq j)}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a993229c4fc95eb568b971f89ba9a6ac33975e92) |

| Entropy | H(X)=logB(α)+(α0−K)ψ(α0)−∑j=1K(αj−1)ψ(αj){displaystyle H(X)=log mathrm {B} (alpha )+(alpha _{0}-K)psi (alpha _{0})-sum _{j=1}^{K}(alpha _{j}-1)psi (alpha _{j})}  with α0{displaystyle alpha _{0}}  defined as for variance, above. defined as for variance, above. |

In probability and statistics, the Dirichlet distribution (after Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet), often denoted Dir(α){displaystyle operatorname {Dir} ({boldsymbol {alpha }})}

The infinite-dimensional generalization of the Dirichlet distribution is the Dirichlet process.

Contents

1 Probability density function

1.1 Support

1.2 Special cases

2 Properties

2.1 Moments

2.2 Mode

2.3 Marginal distributions

2.4 Conjugate to categorical/multinomial

2.5 Relation to Dirichlet-multinomial distribution

2.6 Entropy

2.7 Aggregation

2.8 Neutrality

2.9 Characteristic function

2.10 Inequality

3 Related distributions

3.1 Conjugate prior of the Dirichlet distribution

4 Applications

5 Random number generation

5.1 Gamma distribution

5.1.1 Proof

5.2 Marginal beta distributions

6 Intuitive interpretations of the parameters

6.1 The concentration parameter

6.2 String cutting

6.3 Pólya's urn

7 See also

8 References

9 External links

Probability density function

Illustrating how the log of the density function changes when K = 3 as we change the vector α from α = (0.3, 0.3, 0.3) to (2.0, 2.0, 2.0), keeping all the individual αi{displaystyle alpha _{i}}

's equal to each other.

's equal to each other.The Dirichlet distribution of order K ≥ 2 with parameters α1, ..., αK > 0 has a probability density function with respect to Lebesgue measure on the Euclidean space RK−1 given by

- f(x1,…,xK;α1,…,αK)=1B(α)∏i=1Kxiαi−1{displaystyle fleft(x_{1},ldots ,x_{K};alpha _{1},ldots ,alpha _{K}right)={frac {1}{mathrm {B} ({boldsymbol {alpha }})}}prod _{i=1}^{K}x_{i}^{alpha _{i}-1}}

- where {xk}k=1k=K{displaystyle {x_{k}}_{k=1}^{k=K}}

belong to the standard K−1{displaystyle K-1}

simplex, or in other words: ∑i=1Kxi=1 and xi≥0 for all i∈[1,K]{displaystyle sum _{i=1}^{K}x_{i}=1{mbox{ and }}x_{i}geq 0{mbox{ for all }}iin [1,K]}

The normalizing constant is the multivariate Beta function, which can be expressed in terms of the gamma function:

- B(α)=∏i=1KΓ(αi)Γ(∑i=1Kαi),α=(α1,…,αK).{displaystyle mathrm {B} ({boldsymbol {alpha }})={frac {prod _{i=1}^{K}Gamma (alpha _{i})}{Gamma left(sum _{i=1}^{K}alpha _{i}right)}},qquad {boldsymbol {alpha }}=(alpha _{1},ldots ,alpha _{K}).}

Support

The support of the Dirichlet distribution is the set of K-dimensional vectors x{displaystyle {boldsymbol {x}}}

Special cases

A common special case is the symmetric Dirichlet distribution, where all of the elements making up the parameter vector α{displaystyle {boldsymbol {alpha }}}

- f(x1,…,xK−1;α)=Γ(αK)Γ(α)K∏i=1Kxiα−1.{displaystyle f(x_{1},dots ,x_{K-1};alpha )={frac {Gamma (alpha K)}{Gamma (alpha )^{K}}}prod _{i=1}^{K}x_{i}^{alpha -1}.}

When α=1[3], the symmetric Dirichlet distribution is equivalent to a uniform distribution over the open standard (K − 1)-simplex, i.e. it is uniform over all points in its support. This particular distribution is known as the flat Dirichlet distribution. Values of the concentration parameter above 1 prefer variates that are dense, evenly distributed distributions, i.e. all the values within a single sample are similar to each other. Values of the concentration parameter below 1 prefer sparse distributions, i.e. most of the values within a single sample will be close to 0, and the vast majority of the mass will be concentrated in a few of the values.

More generally, the parameter vector is sometimes written as the product αn{displaystyle alpha {boldsymbol {n}}}

^ If we define the concentration parameter as the sum of the Dirichlet parameters for each dimension, the Dirichlet distribution with concentration parameter K, the dimension of the distribution, is the uniform distribution on the (K − 1)-simplex.

Properties

Moments

Let X=(X1,…,XK)∼Dir(α){displaystyle X=(X_{1},ldots ,X_{K})sim operatorname {Dir} (alpha )}

Let

- α0=∑i=1Kαi.{displaystyle alpha _{0}=sum _{i=1}^{K}alpha _{i}.}

Then[4][5]

- E[Xi]=αiα0,{displaystyle operatorname {E} [X_{i}]={frac {alpha _{i}}{alpha _{0}}},}

- Var[Xi]=αi(α0−αi)α02(α0+1).{displaystyle operatorname {Var} [X_{i}]={frac {alpha _{i}(alpha _{0}-alpha _{i})}{alpha _{0}^{2}(alpha _{0}+1)}}.}

Furthermore, if i≠j{displaystyle ineq j}

- Cov[Xi,Xj]=−αiαjα02(α0+1).{displaystyle operatorname {Cov} [X_{i},X_{j}]={frac {-alpha _{i}alpha _{j}}{alpha _{0}^{2}(alpha _{0}+1)}}.}

Note that the matrix so defined is singular.

More generally, moments of Dirichlet-distributed random variables can be expressed as[6]

- E[∏i=1Kxiβi]=B(α+β)B(α)=Γ(∑i=1Kαi)Γ[∑i=1K(αi+βi)]×∏i=1KΓ(αi+βi)Γ(αi).{displaystyle operatorname {E} left[prod _{i=1}^{K}x_{i}^{beta _{i}}right]={frac {Bleft({boldsymbol {alpha }}+{boldsymbol {beta }}right)}{Bleft({boldsymbol {alpha }}right)}}={frac {Gamma left(sum limits _{i=1}^{K}alpha _{i}right)}{Gamma left[sum limits _{i=1}^{K}(alpha _{i}+beta _{i})right]}}times prod _{i=1}^{K}{frac {Gamma (alpha _{i}+beta _{i})}{Gamma (alpha _{i})}}.}

Mode

The mode of the distribution is[7] the vector (x1, ..., xK) with

- xi=αi−1α0−K,αi>1.{displaystyle x_{i}={frac {alpha _{i}-1}{alpha _{0}-K}},qquad alpha _{i}>1.}

Marginal distributions

The marginal distributions are beta distributions:[8]

- Xi∼Beta(αi,α0−αi).{displaystyle X_{i}sim operatorname {Beta} (alpha _{i},alpha _{0}-alpha _{i}).}

Conjugate to categorical/multinomial

The Dirichlet distribution is the conjugate prior distribution of the categorical distribution (a generic discrete probability distribution with a given number of possible outcomes) and multinomial distribution (the distribution over observed counts of each possible category in a set of categorically distributed observations). This means that if a data point has either a categorical or multinomial distribution, and the prior distribution of the distribution's parameter (the vector of probabilities that generates the data point) is distributed as a Dirichlet, then the posterior distribution of the parameter is also a Dirichlet. Intuitively, in such a case, starting from what we know about the parameter prior to observing the data point, we then can update our knowledge based on the data point and end up with a new distribution of the same form as the old one. This means that we can successively update our knowledge of a parameter by incorporating new observations one at a time, without running into mathematical difficulties.

Formally, this can be expressed as follows. Given a model

- α=(α1,…,αK)=concentration hyperparameterp∣α=(p1,…,pK)∼Dir(K,α)X∣p=(x1,…,xK)∼Cat(K,p){displaystyle {begin{array}{rcccl}{boldsymbol {alpha }}&=&left(alpha _{1},ldots ,alpha _{K}right)&=&{text{concentration hyperparameter}}\mathbf {p} mid {boldsymbol {alpha }}&=&left(p_{1},ldots ,p_{K}right)&sim &operatorname {Dir} (K,{boldsymbol {alpha }})\mathbb {X} mid mathbf {p} &=&left(mathbf {x} _{1},ldots ,mathbf {x} _{K}right)&sim &operatorname {Cat} (K,mathbf {p} )end{array}}}

then the following holds:

- c=(c1,…,cK)=number of occurrences of category ip∣X,α∼Dir(K,c+α)=Dir(K,c1+α1,…,cK+αK){displaystyle {begin{array}{rcccl}mathbf {c} &=&left(c_{1},ldots ,c_{K}right)&=&{text{number of occurrences of category }}i\mathbf {p} mid mathbb {X} ,{boldsymbol {alpha }}&sim &operatorname {Dir} (K,mathbf {c} +{boldsymbol {alpha }})&=&operatorname {Dir} left(K,c_{1}+alpha _{1},ldots ,c_{K}+alpha _{K}right)end{array}}}

This relationship is used in Bayesian statistics to estimate the underlying parameter p of a categorical distribution given a collection of N samples. Intuitively, we can view the hyperprior vector α as pseudocounts, i.e. as representing the number of observations in each category that we have already seen. Then we simply add in the counts for all the new observations (the vector c) in order to derive the posterior distribution.

In Bayesian mixture models and other hierarchical Bayesian models with mixture components, Dirichlet distributions are commonly used as the prior distributions for the categorical variables appearing in the models. See the section on applications below for more information.

Relation to Dirichlet-multinomial distribution

In a model where a Dirichlet prior distribution is placed over a set of categorical-valued observations, the marginal joint distribution of the observations (i.e. the joint distribution of the observations, with the prior parameter marginalized out) is a Dirichlet-multinomial distribution. This distribution plays an important role in hierarchical Bayesian models, because when doing inference over such models using methods such as Gibbs sampling or variational Bayes, Dirichlet prior distributions are often marginalized out. See the article on this distribution for more details.

Entropy

If X is a Dir(α) random variable, the information entropy of X:[9] is

- H(X)=logB(α)+(α0−K)ψ(α0)−∑j=1K(αj−1)ψ(αj){displaystyle H(X)=log operatorname {B} ({boldsymbol {alpha }})+(alpha _{0}-K)psi (alpha _{0})-sum _{j=1}^{K}(alpha _{j}-1)psi (alpha _{j})}

here ψ{displaystyle psi }

The following formula for E[log(Xi)]{displaystyle operatorname {E} [log(X_{i})]}![operatorname {E} [log(X_{i})]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a6fbfec78bf1fad00459b724f09b31c9245b1ba3)

- E[log(Xi)]=ψ(αi)−ψ(α0){displaystyle operatorname {E} [log(X_{i})]=psi (alpha _{i})-psi (alpha _{0})}

and

- Cov[log(Xi),log(Xj)]=ψ′(αi)δij−ψ′(α0){displaystyle operatorname {Cov} [log(X_{i}),log(X_{j})]=psi '(alpha _{i})delta _{ij}-psi '(alpha _{0})}

where ψ{displaystyle psi }

The spectrum of Rényi information for values other than λ=1{displaystyle lambda =1}

- FR(λ)=(1−λ)−1(−λlogB(α)+∑j=1KlogΓ(λ(αi−1)+1)−logΓ(λ(α0−d)+d)){displaystyle F_{R}(lambda )=(1-lambda )^{-1}left(-lambda log mathrm {B} (alpha )+sum _{j=1}^{K}log Gamma (lambda (alpha _{i}-1)+1)-log Gamma (lambda (alpha _{0}-d)+d)right)}

and the information entropy is the limit as λ{displaystyle lambda }

Aggregation

If

- X=(X1,…,XK)∼Dir(α1,…,αK){displaystyle X=(X_{1},ldots ,X_{K})sim operatorname {Dir} (alpha _{1},ldots ,alpha _{K})}

then, if the random variables with subscripts i and j are dropped from the vector and replaced by their sum,

- X′=(X1,…,Xi+Xj,…,XK)∼Dir(α1,…,αi+αj,…,αK).{displaystyle X'=(X_{1},ldots ,X_{i}+X_{j},ldots ,X_{K})sim operatorname {Dir} (alpha _{1},ldots ,alpha _{i}+alpha _{j},ldots ,alpha _{K}).}

This aggregation property may be used to derive the marginal distribution of Xi{displaystyle X_{i}}

Neutrality

If X=(X1,…,XK)∼Dir(α){displaystyle X=(X_{1},ldots ,X_{K})sim operatorname {Dir} (alpha )}

- X(−K)=(X11−XK,X21−XK,…,XK−11−XK),{displaystyle X^{(-K)}=left({frac {X_{1}}{1-X_{K}}},{frac {X_{2}}{1-X_{K}}},ldots ,{frac {X_{K-1}}{1-X_{K}}}right),}

and similarly for removing any of X2,…,XK−1{displaystyle X_{2},ldots ,X_{K-1}}

Combining this with the property of aggregation it follows that Xj + ... + XK is independent of (X1X1+…+Xj−1,X2X1+…+Xj−1,…,Xj−1X1+…+Xj−1){displaystyle left({frac {X_{1}}{X_{1}+ldots +X_{j-1}}},{frac {X_{2}}{X_{1}+ldots +X_{j-1}}},ldots ,{frac {X_{j-1}}{X_{1}+ldots +X_{j-1}}}right)}

Characteristic function

The characteristic function of the Dirichlet distribution is a confluent form of the Lauricella hypergeometric series. It is given by Phillips[13] as

- CF(s1,…,sK−1)=E(ei(s1X1+⋯+sK−1XK−1))=Ψ[K−1](α1,…,αK−1;α;is1,…,isK−1){displaystyle CFleft(s_{1},ldots ,s_{K-1}right)=operatorname {E} left(e^{ileft(s_{1}X_{1}+cdots +s_{K-1}X_{K-1}right)}right)=Psi ^{left[K-1right]}(alpha _{1},ldots ,alpha _{K-1};alpha ;is_{1},ldots ,is_{K-1})}

where α=α1+⋯+αK{displaystyle alpha =alpha _{1}+cdots +alpha _{K}}

- Ψ[m](a1,…,am;c;z1,…zm)=∑(a1)k1⋯(am)kmz1k1⋯zmkm(c)kk1!⋯km!.{displaystyle Psi ^{[m]}(a_{1},ldots ,a_{m};c;z_{1},ldots z_{m})=sum {frac {(a_{1})_{k_{1}}cdots (a_{m})_{k_{m}},z_{1}^{k_{1}}cdots z_{m}^{k_{m}}}{(c)_{k},k_{1}!cdots k_{m}!}}.}

The sum is over non-negative integers k1,…,km{displaystyle k_{1},ldots ,k_{m}}

- Ψ[m]=Γ(c)2πi∫Letta1+⋯+am−c∏j=1m(t−zj)−ajdt{displaystyle Psi ^{[m]}={frac {Gamma (c)}{2pi i}}int _{L}e^{t},t^{a_{1}+cdots +a_{m}-c},prod _{j=1}^{m}(t-z_{j})^{-a_{j}},dt}

where L denotes any path in the complex plane originating at −∞{displaystyle -infty }

Inequality

Probability density function f(x1,…,xK−1;α1,…,αK){displaystyle fleft(x_{1},ldots ,x_{K-1};alpha _{1},ldots ,alpha _{K}right)}

[14].

Related distributions

For K independently distributed Gamma distributions:

- Y1∼Gamma(α1,θ),…,YK∼Gamma(αK,θ){displaystyle Y_{1}sim operatorname {Gamma} (alpha _{1},theta ),ldots ,Y_{K}sim operatorname {Gamma} (alpha _{K},theta )}

we have:[15]:402

- V=∑i=1KYi∼Gamma(∑i=1Kαi,θ),{displaystyle V=sum _{i=1}^{K}Y_{i}sim operatorname {Gamma} left(sum _{i=1}^{K}alpha _{i},theta right),}

- X=(X1,…,XK)=(Y1V,…,YKV)∼Dir(α1,…,αK).{displaystyle X=(X_{1},ldots ,X_{K})=left({frac {Y_{1}}{V}},ldots ,{frac {Y_{K}}{V}}right)sim operatorname {Dir} left(alpha _{1},ldots ,alpha _{K}right).}

Although the Xis are not independent from one another, they can be seen to be generated from a set of K independent gamma random variable.[15]:594 Unfortunately, since the sum V is lost in forming X (in fact it can be shown that V is stochastically independent of X), it is not possible to recover the original gamma random variables from these values alone. Nevertheless, because independent random variables are simpler to work with, this reparametrization can still be useful for proofs about properties of the Dirichlet distribution.

Conjugate prior of the Dirichlet distribution

Because the Dirichlet distribution is an exponential family distribution it has a conjugate prior.

The conjugate prior is of the form:[16]

- CD(α∣v,η)∝(1B(α))ηexp(−∑kvkαk).{displaystyle operatorname {CD} ({boldsymbol {alpha }}mid {boldsymbol {v}},eta )propto left({frac {1}{operatorname {B} ({boldsymbol {alpha }})}}right)^{eta }exp left(-sum _{k}v_{k}alpha _{k}right).}

Here v{displaystyle {boldsymbol {v}}}

- ∀kvk>0 and η>−1 and (η≤0 or ∑kexp−vkη<1){displaystyle forall k;;v_{k}>0;;;;{text{ and }};;;;eta >-1;;;;{text{ and }};;;;(eta leq 0;;;;{text{ or }};;;;sum _{k}exp -{frac {v_{k}}{eta }}<1)}

Given a single observed Dirichlet observation α{displaystyle {boldsymbol {alpha }}}

- CD(⋅∣v−logα,η+1).{displaystyle operatorname {CD} (cdot mid {boldsymbol {v}}-log {boldsymbol {alpha }},eta +1).}

In the published literature there is no practical algorithm to efficiently generate samples from CD(α∣v,η){displaystyle operatorname {CD} ({boldsymbol {alpha }}mid {boldsymbol {v}},eta )}

Applications

Dirichlet distributions are most commonly used as the prior distribution of categorical variables or multinomial variables in Bayesian mixture models and other hierarchical Bayesian models. (Note that in many fields, such as in natural language processing, categorical variables are often imprecisely called "multinomial variables". Such a usage is unlikely to cause confusion, just as when Bernoulli distributions and binomial distributions are commonly conflated.)

Inference over hierarchical Bayesian models is often done using Gibbs sampling, and in such a case, instances of the Dirichlet distribution are typically marginalized out of the model by integrating out the Dirichlet random variable. This causes the various categorical variables drawn from the same Dirichlet random variable to become correlated, and the joint distribution over them assumes a Dirichlet-multinomial distribution, conditioned on the hyperparameters of the Dirichlet distribution (the concentration parameters). One of the reasons for doing this is that Gibbs sampling of the Dirichlet-multinomial distribution is extremely easy; see that article for more information.

Random number generation

Gamma distribution

With a source of Gamma-distributed random variates, one can easily sample a random vector x=(x1,…,xK){displaystyle x=(x_{1},ldots ,x_{K})}

- Gamma(αi,1)=yiαi−1e−yiΓ(αi),{displaystyle operatorname {Gamma} (alpha _{i},1)={frac {y_{i}^{alpha _{i}-1};e^{-y_{i}}}{Gamma (alpha _{i})}},!}

and then set

- xi=yi∑j=1Kyj.{displaystyle x_{i}={frac {y_{i}}{sum _{j=1}^{K}y_{j}}}.}

Proof

The joint distribution of {yi}{displaystyle {y_{i}}}

- e−∑iyi∏i=1Kyiαi−1Γ(αi){displaystyle e^{-sum _{i}y_{i}}prod _{i=1}^{K}{frac {y_{i}^{alpha _{i}-1}}{Gamma (alpha _{i})}}}

Next, one uses a change of variables, parametrising {yi}{displaystyle {y_{i}}}

One must then use the change of variables formula, P(x)=P(y(x))|∂y∂x|{displaystyle P(x)=P(y(x)){bigg |}{frac {partial y}{partial x}}{bigg |}}

Writing y explicitly as a function of x, one obtains y1=xKx1,y2=xKx2…yK−1=xK−1xK,yK=xK(1−∑i=1K−1xi){displaystyle y_{1}=x_{K}x_{1},y_{2}=x_{K}x_{2}ldots y_{K-1}=x_{K-1}x_{K},y_{K}=x_{K}(1-sum _{i=1}^{K-1}x_{i})}

The Jacobian now looks like

- |xK0…x10xK…x2⋮⋮⋱⋮−xK−xK…1−∑i=1K−1xi|{displaystyle {begin{vmatrix}x_{K}&0&ldots &x_{1}\0&x_{K}&ldots &x_{2}\vdots &vdots &ddots &vdots \-x_{K}&-x_{K}&ldots &1-sum _{i=1}^{K-1}x_{i}end{vmatrix}}}

The determinant can be evaluated by noting that it remains unchanged if multiples of a row are added to another row, and adding each of the first K-1 rows to the bottom row to obtain

- |xK0…x10xK…x2⋮⋮⋱⋮00…1|{displaystyle {begin{vmatrix}x_{K}&0&ldots &x_{1}\0&x_{K}&ldots &x_{2}\vdots &vdots &ddots &vdots \0&0&ldots &1end{vmatrix}}}

which can be expanded about the bottom row to obtain xKK−1{displaystyle x_{K}^{K-1}}

Substituting for x in the joint pdf and including the Jacobian, one obtains:

- [∏i=1K−1(xixK)αi−1][xK(1−∑i=1K−1xi)]αK−1∏i=1KΓ(αi)xKK−1e−xK{displaystyle {frac {left[prod _{i=1}^{K-1}(x_{i}x_{K})^{alpha _{i}-1}right]left[x_{K}(1-sum _{i=1}^{K-1}x_{i})right]^{alpha _{K}-1}}{prod _{i=1}^{K}Gamma (alpha _{i})}}x_{K}^{K-1}e^{-x_{K}}}

Note that each of the variables 0≤x1,x2,…,xk−1≤1{displaystyle 0leq x_{1},x_{2},ldots ,x_{k-1}leq 1}

Finally, integrate out the extra degree of freedom xK{displaystyle x_{K}}

- x1,x2,…,xK−1∼(1−∑i=1K−1xi)αK−1∏i=1K−1xiαi−1B(α_){displaystyle x_{1},x_{2},ldots ,x_{K-1}sim {frac {(1-sum _{i=1}^{K-1}x_{i})^{alpha _{K}-1}prod _{i=1}^{K-1}x_{i}^{alpha _{i}-1}}{B({underline {alpha }})}}}

Which is equivalent to

∏i=1Kxiαi−1B(α_){displaystyle {frac {prod _{i=1}^{K}x_{i}^{alpha _{i}-1}}{B({underline {alpha }})}}}with support ∑i=1Kxi=1{displaystyle sum _{i=1}^{K}x_{i}=1}

Below is example Python code to draw the sample:

params = [a1, a2, ..., ak]

sample = [random.gammavariate(a,1) for a in params]

sample = [v/sum(sample) for v in sample]

This formulation is correct regardless of how the Gamma distributions are parameterized (shape/scale vs. shape/rate) because they are equivalent when scale and rate equal 1.0.

Marginal beta distributions

A less efficient algorithm[18] relies on the univariate marginal and conditional distributions being beta and proceeds as follows. Simulate x1{displaystyle x_{1}}

- Beta(α1,∑i=2Kαi){displaystyle {textrm {Beta}}left(alpha _{1},sum _{i=2}^{K}alpha _{i}right)}

Then simulate x2,…,xK−1{displaystyle x_{2},ldots ,x_{K-1}}

- Beta(αj,∑i=j+1Kαi),{displaystyle {textrm {Beta}}left(alpha _{j},sum _{i=j+1}^{K}alpha _{i}right),}

and let

- xj=(1−∑i=1j−1xi)ϕj.{displaystyle x_{j}=left(1-sum _{i=1}^{j-1}x_{i}right)phi _{j}.}

Finally, set

- xK=1−∑i=1K−1xi.{displaystyle x_{K}=1-sum _{i=1}^{K-1}x_{i}.}

This iterative procedure corresponds closely to the "string cutting" intuition described below.

Below is example Python code to draw the sample:

params = [a1, a2, ..., ak]

xs = [random.betavariate(params[0], sum(params[1:]))]

for j in range(1,len(params)-1):

phi = random.betavariate(params[j], sum(params[j+1:]))

xs.append((1-sum(xs)) * phi)

xs.append(1-sum(xs))

Intuitive interpretations of the parameters

The concentration parameter

Dirichlet distributions are very often used as prior distributions in Bayesian inference. The simplest and perhaps most common type of Dirichlet prior is the symmetric Dirichlet distribution, where all parameters are equal. This corresponds to the case where you have no prior information to favor one component over any other. As described above, the single value α to which all parameters are set is called the concentration parameter. If the sample space of the Dirichlet distribution is interpreted as a discrete probability distribution, then intuitively the concentration parameter can be thought of as determining how "concentrated" the probability mass of a sample from a Dirichlet distribution is likely to be. With a value much less than 1, the mass will be highly concentrated in a few components, and all the rest will have almost no mass. With a value much greater than 1, the mass will be dispersed almost equally among all the components. See the article on the concentration parameter for further discussion.

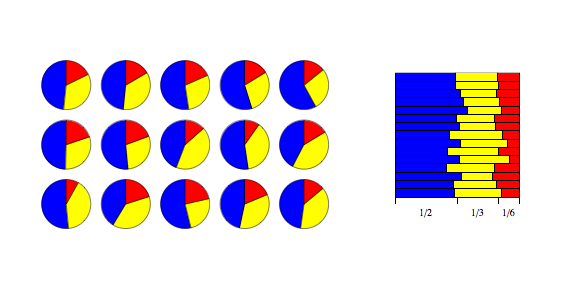

String cutting

One example use of the Dirichlet distribution is if one wanted to cut strings (each of initial length 1.0) into K pieces with different lengths, where each piece had a designated average length, but allowing some variation in the relative sizes of the pieces. The α/α0 values specify the mean lengths of the cut pieces of string resulting from the distribution. The variance around this mean varies inversely with α0.

Pólya's urn

Consider an urn containing balls of K different colors. Initially, the urn contains α1 balls of color 1, α2 balls of color 2, and so on. Now perform N draws from the urn, where after each draw, the ball is placed back into the urn with an additional ball of the same color. In the limit as N approaches infinity, the proportions of different colored balls in the urn will be distributed as Dir(α1,...,αK).[19]

For a formal proof, note that the proportions of the different colored balls form a bounded [0,1]K-valued martingale, hence by the martingale convergence theorem, these proportions converge almost surely and in mean to a limiting random vector. To see that this limiting vector has the above Dirichlet distribution, check that all mixed moments agree.

Note that each draw from the urn modifies the probability of drawing a ball of any one color from the urn in the future. This modification diminishes with the number of draws, since the relative effect of adding a new ball to the urn diminishes as the urn accumulates increasing numbers of balls.

See also

- Generalized Dirichlet distribution

- Grouped Dirichlet distribution

- Inverted Dirichlet distribution

- Latent Dirichlet allocation

- Dirichlet process

- Matrix variate Dirichlet distribution

References

^ S. Kotz; N. Balakrishnan; N. L. Johnson (2000). Continuous Multivariate Distributions. Volume 1: Models and Applications. New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-18387-7..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em} (Chapter 49: Dirichlet and Inverted Dirichlet Distributions)

^ Olkin, Ingram; Rubin, Herman (1964). "Multivariate Beta Distributions and Independence Properties of the Wishart Distribution". The Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 35 (1): 261–269. JSTOR 2238036.

^ ab Bela A. Frigyik; Amol Kapila; Maya R. Gupta (2010). "Introduction to the Dirichlet Distribution and Related Processes" (Technical Report UWEETR-2010-006). University of Washington Department of Electrical Engineering. Retrieved May 2012. Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)

^ Eq. (49.9) on page 488 of Kotz, Balakrishnan & Johnson (2000). Continuous Multivariate Distributions. Volume 1: Models and Applications. New York: Wiley.

^ BalakrishV. B. (2005). ""Chapter 27. Dirichlet Distribution"". A Primer on Statistical Distributions. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 274. ISBN 978-0-471-42798-8.

^ Hoffmann, Till. "Moments of the Dirichlet distribution". Retrieved 13 September 2014.

^ Christopher M. Bishop (17 August 2006). Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-31073-2.

^ Farrow, Malcolm. "MAS3301 Bayesian Statistics" (PDF). Newcastle University. Newcastle University. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

^ Lin, Jiayu (2016). On The Dirichlet Distribution (PDF). Kingston, Canada: Queen's University. pp. § 2.4.9.

^ Song, Kai-Sheng (2001). "Rényi information, loglikelihood, and an intrinsic distribution measure". Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference. Elsevier. 93 (325): 51–69. doi:10.1016/S0378-3758(00)00169-5.

^ Connor, Robert J.; Mosimann, James E (1969). "Concepts of Independence for Proportions with a Generalization of the Dirichlet Distribution". Journal of the American Statistical Association. American Statistical Association. 64 (325): 194–206. doi:10.2307/2283728. JSTOR 2283728.

^ See Kotz, Balakrishnan & Johnson (2000), Section 8.5, "Connor and Mosimann's Generalization", pp. 519–521.

^ P. C. B. Phillips 1988. "The characteristic function of the Dirichlet and multivariate F distribution", Cowles Foundation discussion paper 985

^ Grinshpan, A. Z. (2017). "An inequality for multiple convolutions with respect to Dirichlet probability measure". Advances in Applied Mathematics. 82 (1): 102–119. doi:10.1016/j.aam.2016.08.001.

^ ab Devroye, Luc (1986). Non-Uniform Random Variate Generation. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-96305-7.

^ Lefkimmiatis et al., 2009 [1]. Bayesian Inference on Multiscale Models for Poisson Intensity Estimation: Applications to Photon-Limited Image Denoising. IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON IMAGE PROCESSING, VOL. 18, NO. 8, AUGUST 2009

^ Andreoli, Jean-Marc, 2018 [2]. A conjugate prior for the Dirichlet distribution. Arxiv 1811.05266

^ A. Gelman; J. B. Carlin; H. S. Stern; D. B. Rubin (2003). Bayesian Data Analysis (2nd ed.). p. 582. ISBN 1-58488-388-X.

^ Blackwell, David; MacQueen, James B. (1973). "Ferguson distributions via Polya urn schemes". Ann. Stat. 1 (2): 353–355. doi:10.1214/aos/1176342372.

External links

Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001) [1994], "Dirichlet distribution", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Dirichlet Distribution

- How to estimate the parameters of the compound Dirichlet distribution (Pólya distribution) using expectation-maximization (EM)

Luc Devroye. "Non-Uniform Random Variate Generation". Retrieved May 2012. Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)

- Dirichlet Random Measures, Method of Construction via Compound Poisson Random Variables, and Exchangeability Properties of the resulting Gamma Distribution

SciencesPo: R package that contains functions for simulating parameters of the Dirichlet distribution.

![{displaystyle sum _{i=1}^{K}x_{i}=1{mbox{ and }}x_{i}geq 0{mbox{ for all }}iin [1,K]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/15e9f7b08d8d5bac07e921c61f2b6d5f35335a1f)

![{displaystyle operatorname {E} [X_{i}]={frac {alpha _{i}}{alpha _{0}}},}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/37c9aba7bdae5b779bbb3d3fc2de3e5aeb42d294)

![{displaystyle operatorname {Var} [X_{i}]={frac {alpha _{i}(alpha _{0}-alpha _{i})}{alpha _{0}^{2}(alpha _{0}+1)}}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8c608bbee58907394cddf7cfde0c50e76da86f7a)

![{displaystyle operatorname {Cov} [X_{i},X_{j}]={frac {-alpha _{i}alpha _{j}}{alpha _{0}^{2}(alpha _{0}+1)}}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/879523bb546e76e2cdc7b418517ede223515f6bd)

![{displaystyle operatorname {E} left[prod _{i=1}^{K}x_{i}^{beta _{i}}right]={frac {Bleft({boldsymbol {alpha }}+{boldsymbol {beta }}right)}{Bleft({boldsymbol {alpha }}right)}}={frac {Gamma left(sum limits _{i=1}^{K}alpha _{i}right)}{Gamma left[sum limits _{i=1}^{K}(alpha _{i}+beta _{i})right]}}times prod _{i=1}^{K}{frac {Gamma (alpha _{i}+beta _{i})}{Gamma (alpha _{i})}}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f4936cb169530f4b7afdfa92142b0e9291fbfa9a)

![operatorname {E} [log(X_{i})]=psi (alpha _{i})-psi (alpha _{0})](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/acea912fe4ca84e22cbb8c5e6303d24bf7a0f4fd)

![operatorname {Cov} [log(X_{i}),log(X_{j})]=psi '(alpha _{i})delta _{ij}-psi '(alpha _{0})](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1aea8317bb174f8433722664136d0ccb6619c8f5)

![{displaystyle CFleft(s_{1},ldots ,s_{K-1}right)=operatorname {E} left(e^{ileft(s_{1}X_{1}+cdots +s_{K-1}X_{K-1}right)}right)=Psi ^{left[K-1right]}(alpha _{1},ldots ,alpha _{K-1};alpha ;is_{1},ldots ,is_{K-1})}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/df7c8a54dc3d99a0dd963a0bd6369b1d5fc117ab)

![{displaystyle Psi ^{[m]}(a_{1},ldots ,a_{m};c;z_{1},ldots z_{m})=sum {frac {(a_{1})_{k_{1}}cdots (a_{m})_{k_{m}},z_{1}^{k_{1}}cdots z_{m}^{k_{m}}}{(c)_{k},k_{1}!cdots k_{m}!}}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/842b921fefdc02d65c732267f532a76b231532a9)

![{displaystyle Psi ^{[m]}={frac {Gamma (c)}{2pi i}}int _{L}e^{t},t^{a_{1}+cdots +a_{m}-c},prod _{j=1}^{m}(t-z_{j})^{-a_{j}},dt}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7ea05e80d5aeb9efc0218f02994cb87f35ca7bbc)

![{displaystyle {frac {left[prod _{i=1}^{K-1}(x_{i}x_{K})^{alpha _{i}-1}right]left[x_{K}(1-sum _{i=1}^{K-1}x_{i})right]^{alpha _{K}-1}}{prod _{i=1}^{K}Gamma (alpha _{i})}}x_{K}^{K-1}e^{-x_{K}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/22beb21252592f6326746dfa140e1f838ecc0854)

Comments

Post a Comment