Density functional theory

Electronic structure methods |

|---|

Valence bond theory |

Coulson–Fischer theory Generalized valence bond Modern valence bond |

Molecular orbital theory |

Hartree–Fock method Density functional theory Semi-empirical quantum chemistry methods Møller–Plesset perturbation theory Configuration interaction Coupled cluster Multi-configurational self-consistent field Quantum chemistry composite methods Quantum Monte Carlo |

Electronic band structure |

Nearly free electron model Tight binding Muffin-tin approximation k·p perturbation theory Empty lattice approximation |

Density functional theory (DFT) is a computational quantum mechanical modelling method used in physics, chemistry and materials science to investigate the electronic structure (or nuclear structure) (principally the ground state) of many-body systems, in particular atoms, molecules, and the condensed phases. Using this theory, the properties of a many-electron system can be determined by using functionals, i.e. functions of another function, which in this case is the spatially dependent electron density. Hence the name density functional theory comes from the use of functionals of the electron density. DFT is among the most popular and versatile methods available in condensed-matter physics, computational physics, and computational chemistry.

DFT has been very popular for calculations in solid-state physics since the 1970s. However, DFT was not considered accurate enough for calculations in quantum chemistry until the 1990s, when the approximations used in the theory were greatly refined to better model the exchange and correlation interactions. Computational costs are relatively low when compared to traditional methods, such as exchange only Hartree–Fock theory and its descendants that include electron correlation.

Despite recent improvements, there are still difficulties in using density functional theory to properly describe: intermolecular interactions (of critical importance to understanding chemical reactions), especially van der Waals forces (dispersion); charge transfer excitations; transition states, global potential energy surfaces, dopant interactions and some strongly correlated systems; and in calculations of the band gap and ferromagnetism in semiconductors.[1] The incomplete treatment of dispersion can adversely affect the accuracy of DFT (at least when used alone and uncorrected) in the treatment of systems which are dominated by dispersion (e.g. interacting noble gas atoms)[2] or where dispersion competes significantly with other effects (e.g. in biomolecules).[3] The development of new DFT methods designed to overcome this problem, by alterations to the functional[4] or by the inclusion of additive terms,[5][6][7][8] is a current research topic.

Contents

1 Overview of method

1.1 Origins

2 Derivation and formalism

3 Relativistic density functional theory (explicit functional forms)

4 Approximations (exchange–correlation functionals)

5 Generalizations to include magnetic fields

6 Applications

7 Thomas–Fermi model

8 Hohenberg–Kohn theorems

9 Pseudo-potentials

9.1 Ab initio pseudo-potentials

10 Electron smearing

11 Software supporting DFT

12 See also

13 Lists

14 References

15 Key papers

16 External links

Overview of method

In the context of computational materials science, ab initio (from first principles) DFT calculations allow the prediction and calculation of material behaviour on the basis of quantum mechanical considerations, without requiring higher order parameters such as fundamental material properties. In contemporary DFT techniques the electronic structure is evaluated using a potential acting on the system’s electrons. This DFT potential is constructed as the sum of external potentials Vext, which is determined solely by the structure and the elemental composition of the system, and an effective potential Veff, which represents interelectronic interactions. Thus, a problem for a representative supercell of a material with n electrons can be studied as a set of n one-electron Schrödinger-like equations, which are also known as Kohn–Sham equations.[9]

Origins

Although density functional theory has its roots in the Thomas–Fermi model for the electronic structure of materials, DFT was first put on a firm theoretical footing by Walter Kohn and Pierre Hohenberg in the framework of the two Hohenberg–Kohn theorems (H–K).[10] The original H–K theorems held only for non-degenerate ground states in the absence of a magnetic field, although they have since been generalized to encompass these.[11][12]

The first H–K theorem demonstrates that the ground state properties of a many-electron system are uniquely determined by an electron density that depends on only three spatial coordinates. It set down the groundwork for reducing the many-body problem of N electrons with 3N spatial coordinates to three spatial coordinates, through the use of functionals of the electron density. This theorem has since been extended to the time-dependent domain to develop time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT), which can be used to describe excited states.

The second H–K theorem defines an energy functional for the system and proves that the correct ground state electron density minimizes this energy functional.

In work that later won them the Nobel prize in chemistry, The H–K theorem was further developed by Walter Kohn and Lu Jeu Sham to produce Kohn–Sham DFT (KS DFT). Within this framework, the intractable many-body problem of interacting electrons in a static external potential is reduced to a tractable problem of noninteracting electrons moving in an effective potential. The effective potential includes the external potential and the effects of the Coulomb interactions between the electrons, e.g., the exchange and correlation interactions. Modeling the latter two interactions becomes the difficulty within KS DFT. The simplest approximation is the local-density approximation (LDA), which is based upon exact exchange energy for a uniform electron gas, which can be obtained from the Thomas–Fermi model, and from fits to the correlation energy for a uniform electron gas. Non-interacting systems are relatively easy to solve as the wavefunction can be represented as a Slater determinant of orbitals. Further, the kinetic energy functional of such a system is known exactly. The exchange–correlation part of the total energy functional remains unknown and must be approximated.

Another approach, less popular than KS DFT but arguably more closely related to the spirit of the original H–K theorems, is orbital-free density functional theory (OFDFT), in which approximate functionals are also used for the kinetic energy of the noninteracting system.

Derivation and formalism

As usual in many-body electronic structure calculations, the nuclei of the treated molecules or clusters are seen as fixed (the Born–Oppenheimer approximation), generating a static external potential V in which the electrons are moving. A stationary electronic state is then described by a wavefunction Ψ(r1→,…,rN→) satisfying the many-electron time-independent Schrödinger equation

- H^Ψ=[T^+V^+U^]Ψ=[∑iN(−ℏ22mi∇i2)+∑iNV(r→i)+∑i<jNU(r→i,r→j)]Ψ=EΨ{displaystyle {hat {H}}Psi =left[{hat {T}}+{hat {V}}+{hat {U}}right]Psi =left[sum _{i}^{N}left(-{frac {hbar ^{2}}{2m_{i}}}nabla _{i}^{2}right)+sum _{i}^{N}Vleft({vec {r}}_{i}right)+sum _{i<j}^{N}Uleft({vec {r}}_{i},{vec {r}}_{j}right)right]Psi =EPsi }

where, for the N-electron system, Ĥ is the Hamiltonian, E is the total energy, T̂ is the kinetic energy, V̂ is the potential energy from the external field due to positively charged nuclei, and Û is the electron–electron interaction energy. The operators T̂ and Û are called universal operators as they are the same for any N-electron system, while V̂ is system-dependent. This complicated many-particle equation is not separable into simpler single-particle equations because of the interaction term Û.

There are many sophisticated methods for solving the many-body Schrödinger equation based on the expansion of the wavefunction in Slater determinants. While the simplest one is the Hartree–Fock method, more sophisticated approaches are usually categorized as post-Hartree–Fock methods. However, the problem with these methods is the huge computational effort, which makes it virtually impossible to apply them efficiently to larger, more complex systems.

Here DFT provides an appealing alternative, being much more versatile as it provides a way to systematically map the many-body problem, with Û, onto a single-body problem without Û. In DFT the key variable is the electron density n(r→), which for a normalized Ψ is given by

- n(r→)=N∫d3r2⋯∫d3rNΨ∗(r→,r→2,…,r→N)Ψ(r→,r→2,…,r→N).{displaystyle nleft({vec {r}}right)=Nint {mathrm {d} }^{3}r_{2}cdots int {mathrm {d} }^{3}r_{N},Psi ^{*}left({vec {r}},{vec {r}}_{2},dots ,{vec {r}}_{N}right)Psi left({vec {r}},{vec {r}}_{2},dots ,{vec {r}}_{N}right).}

This relation can be reversed, i.e., for a given ground-state density n0(r→) it is possible, in principle, to calculate the corresponding ground-state wavefunction Ψ0(r1→,…,rN→). In other words, Ψ is a unique functional of n0,[10]

- Ψ0=Ψ[n0]{displaystyle Psi _{0}=Psi [n_{0}]}

and consequently the ground-state expectation value of an observable Ô is also a functional of n0

- O[n0]=⟨Ψ[n0]|O^|Ψ[n0]⟩.{displaystyle O[n_{0}]=leftlangle Psi [n_{0}]left|{hat {O}}right|Psi [n_{0}]rightrangle .}

In particular, the ground-state energy is a functional of n0

- E0=E[n0]=⟨Ψ[n0]|T^+V^+U^|Ψ[n0]⟩{displaystyle E_{0}=E[n_{0}]=leftlangle Psi [n_{0}]left|{hat {T}}+{hat {V}}+{hat {U}}right|Psi [n_{0}]rightrangle }

where the contribution of the external potential ⟨ Ψ[n0] | V̂ | Ψ[n0] ⟩ can be written explicitly in terms of the ground-state density n0

- V[n0]=∫V(r→)n0(r→)d3r.{displaystyle V[n_{0}]=int Vleft({vec {r}}right)n_{0}left({vec {r}}right),{mathrm {d} }^{3}r.}

More generally, the contribution of the external potential ⟨ Ψ | V̂ | Ψ ⟩ can be written explicitly in terms of the density n,

- V[n]=∫V(r→)n(r→)d3r.{displaystyle V[n]=int V({vec {r}})n({vec {r}}),{mathrm {d} }^{3}r.}

The functionals T[n] and U[n] are called universal functionals, while V[n] is called a non-universal functional, as it depends on the system under study. Having specified a system, i.e., having specified V̂, one then has to minimize the functional

- E[n]=T[n]+U[n]+∫V(r→)n(r→)d3r{displaystyle E[n]=T[n]+U[n]+int V({vec {r}})n({vec {r}}),{mathrm {d} }^{3}r}

with respect to n(r→), assuming one has reliable expressions for T[n] and U[n]. A successful minimization of the energy functional will yield the ground-state density n0 and thus all other ground-state observables.

The variational problems of minimizing the energy functional E[n] can be solved by applying the Lagrangian method of undetermined multipliers.[13] First, one considers an energy functional that does not explicitly have an electron–electron interaction energy term,

- Es[n]=⟨Ψs[n]|T^+V^s|Ψs[n]⟩{displaystyle E_{s}[n]=leftlangle Psi _{mathrm {s} }[n]left|{hat {T}}+{hat {V}}_{mathrm {s} }right|Psi _{mathrm {s} }[n]rightrangle }

where T̂ denotes the kinetic energy operator and V̂s is an external effective potential in which the particles are moving, so that ns(r→) ≝ n(r→).

Thus, one can solve the so-called Kohn–Sham equations of this auxiliary noninteracting system,

- [−ℏ22m∇2+Vs(r→)]φi(r→)=εiφi(r→){displaystyle left[-{frac {hbar ^{2}}{2m}}nabla ^{2}+V_{mathrm {s} }({vec {r}})right]varphi _{i}({vec {r}})=varepsilon _{i}varphi _{i}({vec {r}})}

which yields the orbitals φi that reproduce the density n(r→) of the original many-body system

- n(r→) =def ns(r→)=∑iN|φi(r→)|2.{displaystyle n({vec {r}}) {stackrel {mathrm {def} }{=}} n_{mathrm {s} }({vec {r}})=sum _{i}^{N}left|varphi _{i}({vec {r}})right|^{2}.}

The effective single-particle potential can be written in more detail as

- Vs(r→)=V(r→)+∫e2ns(r→′)|r→−r→′|d3r′+VXC[ns(r→)]{displaystyle V_{mathrm {s} }({vec {r}})=V({vec {r}})+int {frac {e^{2}n_{mathrm {s} }left({vec {r}}'right)}{left|{vec {r}}-{vec {r}}'right|}},{mathrm {d} }^{3}r'+V_{mathrm {XC} }[n_{mathrm {s} }({vec {r}})]}

where the second term denotes the so-called Hartree term describing the electron–electron Coulomb repulsion, while the last term VXC is called the exchange–correlation potential. Here, VXC includes all the many-particle interactions. Since the Hartree term and VXC depend on n(r→), which depends on the φi, which in turn depend on Vs, the problem of solving the Kohn–Sham equation has to be done in a self-consistent (i.e., iterative) way. Usually one starts with an initial guess for n(r→), then calculates the corresponding Vs and solves the Kohn–Sham equations for the φi. From these one calculates a new density and starts again. This procedure is then repeated until convergence is reached. A non-iterative approximate formulation called Harris functional DFT is an alternative approach to this.

Notes

- The one-to-one correspondence between electron density and single-particle potential is not so smooth. It contains kinds of non-analytic structure. Es[n] contains kinds of singularities, cuts and branches. This may indicate a limitation of our hope for representing exchange–correlation functional in a simple analytic form.

- It is possible to extend the DFT idea to the case of the Green function G instead of the density n. It is called as Luttinger–Ward functional (or kinds of similar functionals), written as E[G]. However, G is determined not as its minimum, but as its extremum. Thus we may have some theoretical and practical difficulties.

- There is no one-to-one correspondence between one-body density matrix n(r→,r′→) and the one-body potential V(r→,r′→). (Remember that all the eigenvalues of n(r→,r′→) are 1.) In other words, it ends up with a theory similar to the Hartree–Fock (or hybrid) theory.

Relativistic density functional theory (explicit functional forms)

The same theorems can be proven in the case of relativistic electrons, thereby providing generalization of DFT for the relativistic case. Unlike the nonrelativistic theory, in the relativistic case it is possible to derive a few exact and explicit formulas for the relativistic density functional.

Let one consider an electron in a hydrogen-like ion obeying the relativistic Dirac equation. The Hamiltonian H for a relativistic electron moving in the Coulomb potential can be chosen in the following form (atomic units are used):

- H=c(α→⋅p→)+eV+mc2β,{displaystyle H=c({vec {alpha }}cdot {vec {p}})+eV+mc^{2}beta ,}

where V = −eZ/r is the Coulomb potential of a pointlike nucleus, p→ is a momentum operator of the electron, and e, m and c are the elementary charge, electron mass and the speed of light respectively, and finally α→ and β are a set of Dirac 2 × 2 matrices:

- α→=(0σ→σ→0),β=(I00−I).{displaystyle {begin{aligned}{vec {alpha }}&={begin{pmatrix}0&{vec {sigma }}\{vec {sigma }}&0end{pmatrix}},\beta &={begin{pmatrix}I&0\0&-Iend{pmatrix}}.end{aligned}}}

To find out the eigenfunctions and corresponding energies, one solves the eigenfunction equation

- HΨ=EΨ,{displaystyle HPsi =EPsi ,}

where Ψ = (Ψ(1), Ψ(2), Ψ(3), Ψ(4))T is a four-component wavefunction and E is the associated eigenenergy. It is demonstrated in Brack (1983)[14] that application of the virial theorem to the eigenfunction equation produces the following formula for the eigenenergy of any bound state:

- E=mc2⟨Ψ|β|Ψ⟩=mc2∫|Ψ(1)|2+|Ψ(2)|2−|Ψ(3)|2−|Ψ(4)|2dτ,{displaystyle E=mc^{2}leftlangle Psi left|beta right|Psi rightrangle =mc^{2}int left|Psi (1)right|^{2}+left|Psi (2)right|^{2}-left|Psi (3)right|^{2}-left|Psi (4)right|^{2},mathrm {d} tau ,}

and analogously, the virial theorem applied to the eigenfunction equation with the square of the Hamiltonian[15] yields

E2=m2c4+emc2⟨Ψ|Vβ|Ψ⟩{displaystyle E^{2}=m^{2}c^{4}+emc^{2}leftlangle Psi left|Vbeta right|Psi rightrangle }.

It is easy to see that both of the above formulae represent density functionals. The former formula can be easily generalized for the multi-electron case.[16]

Approximations (exchange–correlation functionals)

The major problem with DFT is that the exact functionals for exchange and correlation are not known except for the free electron gas. However, approximations exist which permit the calculation of certain physical quantities quite accurately.[17] In physics the most widely used approximation is the local-density approximation (LDA), where the functional depends only on the density at the coordinate where the functional is evaluated:

- EXCLDA[n]=∫εXC(n)n(r→)d3r.{displaystyle E_{mathrm {XC} }^{mathrm {LDA} }[n]=int varepsilon _{mathrm {XC} }(n)n({vec {r}}),{mathrm {d} }^{3}r.}

The local spin-density approximation (LSDA) is a straightforward generalization of the LDA to include electron spin:

- EXCLSDA[n↑,n↓]=∫εXC(n↑,n↓)n(r→)d3r.{displaystyle E_{mathrm {XC} }^{mathrm {LSDA} }left[n_{uparrow },n_{downarrow }right]=int varepsilon _{mathrm {XC} }left(n_{uparrow },n_{downarrow }right)n({vec {r}}),{mathrm {d} }^{3}r.}

In LDA, the exchange–correlation energy is typically separated into the exchange part and the correlation part: εXC = εX + εC. The exchange part is called the Dirac (or sometimes Slater) exchange which takes the form εX ∝ n1⁄3. There are, however, many mathematical forms for the correlation part. Highly accurate formulae for the correlation energy density εC(n↑,n↓) have been constructed from quantum Monte Carlo simulations of jellium.[18] A simple first-principles correlation functional has been recently proposed as well.[19][20] Although unrelated to the Monte Carlo simulation, the two variants provide comparable accuracy.[21]

The LDA assumes that the density is the same everywhere. Because of this, the LDA has a tendency to underestimate the exchange energy and over-estimate the correlation energy.[22] The errors due to the exchange and correlation parts tend to compensate each other to a certain degree. To correct for this tendency, it is common to expand in terms of the gradient of the density in order to account for the non-homogeneity of the true electron density. This allows for corrections based on the changes in density away from the coordinate. These expansions are referred to as generalized gradient approximations (GGA)[23][24][25] and have the following form:

- EXCGGA[n↑,n↓]=∫εXC(n↑,n↓,∇n↑,∇n↓)n(r→)d3r.{displaystyle E_{mathrm {XC} }^{mathrm {GGA} }left[n_{uparrow },n_{downarrow }right]=int varepsilon _{mathrm {XC} }left(n_{uparrow },n_{downarrow },nabla n_{uparrow },nabla n_{downarrow }right)n({vec {r}}),{mathrm {d} }^{3}r.}

Using the latter (GGA), very good results for molecular geometries and ground-state energies have been achieved.

Potentially more accurate than the GGA functionals are the meta-GGA functionals, a natural development after the GGA (generalized gradient approximation). Meta-GGA DFT functional in its original form includes the second derivative of the electron density (the Laplacian) whereas GGA includes only the density and its first derivative in the exchange–correlation potential.

Functionals of this type are, for example, TPSS and the Minnesota Functionals. These functionals include a further term in the expansion, depending on the density, the gradient of the density and the Laplacian (second derivative) of the density.

Difficulties in expressing the exchange part of the energy can be relieved by including a component of the exact exchange energy calculated from Hartree–Fock theory. Functionals of this type are known as hybrid functionals.

Generalizations to include magnetic fields

The DFT formalism described above breaks down, to various degrees, in the presence of a vector potential, i.e. a magnetic field. In such a situation, the one-to-one mapping between the ground-state electron density and wavefunction is lost. Generalizations to include the effects of magnetic fields have led to two different theories: current density functional theory (CDFT) and magnetic field density functional theory (BDFT). In both these theories, the functional used for the exchange and correlation must be generalized to include more than just the electron density. In current density functional theory, developed by Vignale and Rasolt,[12] the functionals become dependent on both the electron density and the paramagnetic current density. In magnetic field density functional theory, developed by Salsbury, Grayce and Harris,[26] the functionals depend on the electron density and the magnetic field, and the functional form can depend on the form of the magnetic field. In both of these theories it has been difficult to develop functionals beyond their equivalent to LDA, which are also readily implementable computationally.

Recently an extension by Pan and Sahni[27] extended the Hohenberg–Kohn theorem for varying magnetic fields using the density and the current density as fundamental variables.

Applications

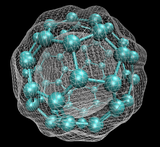

C60 with isosurface of ground-state electron density as calculated with DFT.

In general, density functional theory finds increasingly broad application in chemistry and materials science for the interpretation and prediction of complex system behavior at an atomic scale. Specifically, DFT computational methods are applied for synthesis-related systems and processing parameters. In such systems, experimental studies are often encumbered by inconsistent results and non-equilibrium conditions. Examples of contemporary DFT applications include studying the effects of dopants on phase transformation behavior in oxides, magnetic behavior in dilute magnetic semiconductor materials, and the study of magnetic and electronic behavior in ferroelectrics and dilute magnetic semiconductors.[1][28] It has also been shown that DFT gives good results in the prediction of sensitivity of some nanostructures to environmental pollutants like sulfur dioxide[29] or acrolein[30] as well as prediction of mechanical properties.[31]

In practice, Kohn–Sham theory can be applied in several distinct ways depending on what is being investigated. In solid state calculations, the local density approximations are still commonly used along with plane wave basis sets, as an electron gas approach is more appropriate for electrons which are delocalised through an infinite solid. In molecular calculations, however, more sophisticated functionals are needed, and a huge variety of exchange–correlation functionals have been developed for chemical applications. Some of these are inconsistent with the uniform electron gas approximation; however, they must reduce to LDA in the electron gas limit. Among physicists, one of the most widely used functionals is the revised Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof exchange model (a direct generalized gradient parameterization of the free electron gas with no free parameters); however, this is not sufficiently calorimetrically accurate for gas-phase molecular calculations. In the chemistry community, one popular functional is known as BLYP (from the name Becke for the exchange part and Lee, Yang and Parr for the correlation part). Even more widely used is B3LYP, which is a hybrid functional in which the exchange energy, in this case from Becke's exchange functional, is combined with the exact energy from Hartree–Fock theory. Along with the component exchange and correlation funсtionals, three parameters define the hybrid functional, specifying how much of the exact exchange is mixed in. The adjustable parameters in hybrid functionals are generally fitted to a 'training set' of molecules. Although the results obtained with these functionals are usually sufficiently accurate for most applications, there is no systematic way of improving them (in contrast to some of the traditional wavefunction-based methods like configuration interaction or coupled cluster theory). In the current DFT approach it is not possible to estimate the error of the calculations without comparing them to other methods or experiments.

Thomas–Fermi model

The predecessor to density functional theory was the Thomas–Fermi model, developed independently by both Thomas and Fermi in 1927. They used a statistical model to approximate the distribution of electrons in an atom. The mathematical basis postulated that electrons are distributed uniformly in phase space with two electrons in every h3 of volume.[32] For each element of coordinate space volume d3r we can fill out a sphere of momentum space up to the Fermi momentum pf[33]

- 43πpf3(r→).{displaystyle {tfrac {4}{3}}pi p_{mathrm {f} }^{3}({vec {r}}).}

Equating the number of electrons in coordinate space to that in phase space gives:

- n(r→)=8π3h3pf3(r→).{displaystyle n({vec {r}})={frac {8pi }{3h^{3}}}p_{mathrm {f} }^{3}({vec {r}}).}

Solving for pf and substituting into the classical kinetic energy formula then leads directly to a kinetic energy represented as a functional of the electron density:

- tTF[n]=p22me∝(n13)22me∝n23(r→),TTF[n]=CF∫n(r→)n23(r→)d3r=CF∫n53(r→)d3r,{displaystyle {begin{aligned}t_{mathrm {TF} }[n]&={frac {p^{2}}{2m_{mathrm {e} }}}propto {frac {left(n^{frac {1}{3}}right)^{2}}{2m_{mathrm {e} }}}propto n^{frac {2}{3}}({vec {r}}),\[6pt]T_{mathrm {TF} }[n]&=C_{mathrm {F} }int n({vec {r}})n^{frac {2}{3}}({vec {r}}),mathrm {d} ^{3}r=C_{mathrm {F} }int n^{frac {5}{3}}({vec {r}}),mathrm {d} ^{3}r,end{aligned}}}

where

- CF=3h210me(38π)23.{displaystyle C_{mathrm {F} }={frac {3h^{2}}{10m_{mathrm {e} }}}left({frac {3}{8pi }}right)^{frac {2}{3}}.}

As such, they were able to calculate the energy of an atom using this kinetic energy functional combined with the classical expressions for the nucleus–electron and electron–electron interactions (which can both also be represented in terms of the electron density).

Although this was an important first step, the Thomas–Fermi equation's accuracy is limited because the resulting kinetic energy functional is only approximate, and because the method does not attempt to represent the exchange energy of an atom as a conclusion of the Pauli principle. An exchange energy functional was added by Dirac in 1928.

However, the Thomas–Fermi–Dirac theory remained rather inaccurate for most applications. The largest source of error was in the representation of the kinetic energy, followed by the errors in the exchange energy, and due to the complete neglect of electron correlation.

Teller (1962) showed that Thomas–Fermi theory cannot describe molecular bonding. This can be overcome by improving the kinetic energy functional.

The kinetic energy functional can be improved by adding the Weizsäcker (1935) correction:[34][35]

- TW[n]=ℏ28m∫|∇n(r→)|2n(r→)d3r.{displaystyle T_{mathrm {W} }[n]={frac {hbar ^{2}}{8m}}int {frac {|nabla n({vec {r}})|^{2}}{n({vec {r}})}},mathrm {d} ^{3}r.}

Hohenberg–Kohn theorems

The Hohenberg–Kohn theorems relate to any system consisting of electrons moving under the influence of an external potential.

Theorem 1. The external potential (and hence the total energy), is a unique functional of the electron density.

- If two systems of electrons, one trapped in a potential v1(r→) and the other in v2(r→), have the same ground-state density n(r→) then v1(r→) − v2(r→) is necessarily a constant.

Corollary: the ground state density uniquely determines the potential and thus all properties of the system, including the many-body wavefunction. In particular, the H–K functional, defined as F[n] = T[n] + U[n], is a universal functional of the density (not depending explicitly on the external potential).

Theorem 2. The functional that delivers the ground state energy of the system gives the lowest energy if and only if the input density is the true ground state density.

- For any positive integer N and potential v(r→), a density functional F[n] exists such that

- E(v,N)[n]=F[n]+∫v(r→)n(r→)d3r{displaystyle E_{(v,N)}[n]=F[n]+int v({vec {r}})n({vec {r}}),mathrm {d} ^{3}r}

- E(v,N)[n]=F[n]+∫v(r→)n(r→)d3r{displaystyle E_{(v,N)}[n]=F[n]+int v({vec {r}})n({vec {r}}),mathrm {d} ^{3}r}

- obtains its minimal value at the ground-state density of N electrons in the potential v(r)→. The minimal value of E(v,N)[n] is then the ground state energy of this system.

- For any positive integer N and potential v(r→), a density functional F[n] exists such that

Pseudo-potentials

The many-electron Schrödinger equation can be very much simplified if electrons are divided in two groups: valence electrons and inner core electrons. The electrons in the inner shells are strongly bound and do not play a significant role in the chemical binding of atoms; they also partially screen the nucleus, thus forming with the nucleus an almost inert core. Binding properties are almost completely due to the valence electrons, especially in metals and semiconductors. This separation suggests that inner electrons can be ignored in a large number of cases, thereby reducing the atom to an ionic core that interacts with the valence electrons. The use of an effective interaction, a pseudopotential, that approximates the potential felt by the valence electrons, was first proposed by Fermi in 1934 and Hellmann in 1935. In spite of the simplification pseudo-potentials introduce in calculations, they remained forgotten until the late 1950s.

Ab initio pseudo-potentials

A crucial step toward more realistic pseudo-potentials was given by Topp and Hopfield[36] and more recently Cronin, who suggested that the pseudo-potential should be adjusted such that they describe the valence charge density accurately. Based on that idea, modern pseudo-potentials are obtained inverting the free atom Schrödinger equation for a given reference electronic configuration and forcing the pseudo-wavefunctions to coincide with the true valence wave functions beyond a certain distance rl. The pseudo-wavefunctions are also forced to have the same norm as the true valence wavefunctions and can be written as

- RlPP(r)=RnlAE(r),∫0rl|RlPP(r)|2r2dr=∫0rl|RnlAE(r)|2r2dr,{displaystyle {begin{aligned}R_{l}^{mathrm {PP} }(r)&=R_{nl}^{mathrm {AE} }(r),\[6pt]int _{0}^{rl}left|R_{l}^{mathrm {PP} }(r)right|^{2}r^{2},mathrm {d} r&=int _{0}^{rl}left|R_{nl}^{mathrm {AE} }(r)right|^{2}r^{2},mathrm {d} r,end{aligned}}}

where Rl(r) is the radial part of the wavefunction with angular momentum l; and PP and AE denote, respectively, the pseudo-wavefunction and the true (all-electron) wavefunction. The index n in the true wavefunctions denotes the valence level. The distance beyond which the true and the pseudo-wavefunctions are equal, rl, is also dependent on l.

Electron smearing

The electrons of a system will occupy the lowest Kohn–Sham eigenstates up to a given energy level according to the Aufbau principle. This corresponds to the steplike Fermi–Dirac distribution at absolute zero. If there are several degenerate or close to degenerate eigenstates at the Fermi level, it is possible to get convergence problems, since very small perturbations may change the electron occupation. One way of damping these oscillations is to smear the electrons, i.e. allowing fractional occupancies.[37] One approach of doing this is to assign a finite temperature to the electron Fermi–Dirac distribution. Other ways is to assign a cumulative Gaussian distribution of the electrons or using a Methfessel–Paxton method.[38][39]

Software supporting DFT

DFT is supported by many quantum chemistry and solid state physics software packages, often along with other methods.

See also

- Basis set (chemistry)

- Dynamical mean field theory

- Gas in a box

- Harris functional

- Helium atom

- Kohn–Sham equations

- Local density approximation

- Molecule

- Molecular design software

- Molecular modelling

- Quantum chemistry

- Thomas–Fermi model

- Time-dependent density functional theory

- Car–Parrinello molecular dynamics

Lists

- List of quantum chemistry and solid state physics software

- List of software for molecular mechanics modeling

References

^ ab Assadi, M. H. N.; et al. (2013). "Theoretical study on copper's energetics and magnetism in TiO2 polymorphs". Journal of Applied Physics. 113 (23): 233913–233913–5. arXiv:1304.1854. Bibcode:2013JAP...113w3913A. doi:10.1063/1.4811539..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Van Mourik, Tanja; Gdanitz, Robert J. (2002). "A critical note on density functional theory studies on rare-gas dimers". Journal of Chemical Physics. 116 (22): 9620–9623. Bibcode:2002JChPh.116.9620V. doi:10.1063/1.1476010.

^ Vondrášek, Jiří; Bendová, Lada; Klusák, Vojtěch; Hobza, Pavel (2005). "Unexpectedly strong energy stabilization inside the hydrophobic core of small protein rubredoxin mediated by aromatic residues: correlated ab initio quantum chemical calculations". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 127 (8): 2615–2619. doi:10.1021/ja044607h. PMID 15725017.

^ Grimme, Stefan (2006). "Semiempirical hybrid density functional with perturbative second-order correlation". Journal of Chemical Physics. 124 (3): 034108. Bibcode:2006JChPh.124c4108G. doi:10.1063/1.2148954. PMID 16438568.

^ Zimmerli, Urs; Parrinello, Michele; Koumoutsakos, Petros (2004). "Dispersion corrections to density functionals for water aromatic interactions". Journal of Chemical Physics. 120 (6): 2693–2699. Bibcode:2004JChPh.120.2693Z. doi:10.1063/1.1637034. PMID 15268413.

^ Grimme, Stefan (2004). "Accurate description of van der Waals complexes by density functional theory including empirical corrections". Journal of Computational Chemistry. 25 (12): 1463–1473. doi:10.1002/jcc.20078. PMID 15224390.

^ Von Lilienfeld, O. Anatole; Tavernelli, Ivano; Rothlisberger, Ursula; Sebastiani, Daniel (2004). "Optimization of effective atom centered potentials for London dispersion forces in density functional theory" (PDF). Physical Review Letters. 93 (15): 153004. Bibcode:2004PhRvL..93o3004V. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.153004. PMID 15524874.

^ Tkatchenko, Alexandre; Scheffler, Matthias (2009). "Accurate Molecular Van Der Waals Interactions from Ground-State Electron Density and Free-Atom Reference Data". Physical Review Letters. 102 (7): 073005. Bibcode:2009PhRvL.102g3005T. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.073005. PMID 19257665.

^ Hanaor, D. A. H.; Assadi, M. H. N.; Li, S.; Yu, A.; Sorrell, C. C. (2012). "Ab initio study of phase stability in doped TiO2". Computational Mechanics. 50 (2): 185–194. arXiv:1210.7555. Bibcode:2012CompM..50..185H. doi:10.1007/s00466-012-0728-4.

^ ab Hohenberg, Pierre; Walter, Kohn (1964). "Inhomogeneous electron gas". Physical Review. 136 (3B): B864–B871. Bibcode:1964PhRv..136..864H. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.136.B864.

^ Levy, Mel (1979). "Universal variational functionals of electron densities, first-order density matrices, and natural spin-orbitals and solution of the v-representability problem". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 76 (12): 6062–6065. Bibcode:1979PNAS...76.6062L. doi:10.1073/pnas.76.12.6062. PMC 411802. PMID 16592733.

^ ab Vignale, G.; Rasolt, Mark (1987). "Density-functional theory in strong magnetic fields". Physical Review Letters. 59 (20): 2360–2363. Bibcode:1987PhRvL..59.2360V. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.59.2360. PMID 10035523.

^ Kohn, W.; Sham, L. J. (1965). "Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects". Physical Review. 140 (4A): A1133–A1138. Bibcode:1965PhRv..140.1133K. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.140.A1133.

^ Brack, M. (1983). "Virial theorems for relativistic spin-1⁄2 and spin-0 particles" (PDF). Physical Review D. 27 (8): 1950. Bibcode:1983PhRvD..27.1950B. doi:10.1103/physrevd.27.1950.

^ Koshelev, K. (2015). "About density functional theory interpretation". arXiv:0812.2919 [quant-ph].

^ Koshelev, K. (2007). "Alpha variation problem and q-factor definition". arXiv:0707.1146 [physics.atom-ph].

^ Burke, Kieron; Wagner, Lucas O. (2013). "DFT in a nutshell". International Journal of Quantum Chemistry. 113 (2): 96. doi:10.1002/qua.24259.

^ Perdew, John P.; Ruzsinszky, Adrienn; Tao, Jianmin; Staroverov, Viktor N.; Scuseria, Gustavo; Csonka, Gábor I. (2005). "Prescriptions for the design and selection of density functional approximations: More constraint satisfaction with fewer fits". Journal of Chemical Physics. 123 (6): 062201. Bibcode:2005JChPh.123f2201P. doi:10.1063/1.1904565. PMID 16122287.

^ Chachiyo, Teepanis (2016). "Communication: Simple and accurate uniform electron gas correlation energy for the full range of densities". Journal of Chemical Physics. 145 (2): 021101. Bibcode:2016JChPh.145b1101C. doi:10.1063/1.4958669. PMID 27421388.

^ Fitzgerald, Richard J. (2016). "A simpler ingredient for a complex calculation". Physics Today. 69 (9): 20. Bibcode:2016PhT....69i..20F. doi:10.1063/PT.3.3288.

^ Jitropas, Ukrit; Hsu, Chung-Hao (2017). "Study of the first-principles correlation functional in the calculation of silicon phonon dispersion curves". Japanese Journal of Applied Physics. 56 (7): 070313. Bibcode:2017JaJAP..56g0313J. doi:10.7567/JJAP.56.070313.

^ Becke, Axel D. (2014-05-14). "Perspective: Fifty years of density-functional theory in chemical physics". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 140 (18): A301. Bibcode:2014JChPh.140rA301B. doi:10.1063/1.4869598. ISSN 0021-9606. PMID 24832308.

^ Perdew, John P.; Chevary, J. A.; Vosko, S. H.; Jackson, Koblar A.; Pederson, Mark R.; Singh, D. J.; Fiolhais, Carlos (1992). "Atoms, molecules, solids, and surfaces: Applications of the generalized gradient approximation for exchange and correlation". Physical Review B. 46 (11): 6671. Bibcode:1992PhRvB..46.6671P. doi:10.1103/physrevb.46.6671. hdl:10316/2535.

^ Becke, Axel D. (1988). "Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior". Physical Review A. 38 (6): 3098–3100. Bibcode:1988PhRvA..38.3098B. doi:10.1103/physreva.38.3098. PMID 9900728.

^ Langreth, David C; Mehl, M J (1983). "Beyond the local-density approximation in calculations of ground-state electronic properties". Physical Review B. 28 (4): 1809. Bibcode:1983PhRvB..28.1809L. doi:10.1103/physrevb.28.1809.

^ Grayce, Christopher; Harris, Robert (1994). "Magnetic-field density-functional theory". Physical Review A. 50 (4): 3089–3095. Bibcode:1994PhRvA..50.3089G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.50.3089. PMID 9911249.

^ Viraht, Xiao-Yin (2012). "Hohenberg–Kohn theorem including electron spin". Physical Review A. 86 (4): 042502. Bibcode:2012PhRvA..86d2502P. doi:10.1103/physreva.86.042502.

^ Segall, M. D.; Lindan, P. J. (2002). "First-principles simulation: ideas, illustrations and the CASTEP code". Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 14 (11): 2717. Bibcode:2002JPCM...14.2717S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.467.6857. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/14/11/301.

^ Soleymanabadi, Hamed; Rastegar, Somayeh F. (2014-01-01). "Theoretical investigation on the selective detection of SO2 molecule by AlN nanosheets". Journal of Molecular Modeling. 20 (9): 2439. doi:10.1007/s00894-014-2439-6. PMID 25201451.

^ Soleymanabadi, Hamed; Rastegar, Somayeh F. (2013-01-01). "DFT studies of acrolein molecule adsorption on pristine and Al-doped graphenes". Journal of Molecular Modeling. 19 (9): 3733–3740. doi:10.1007/s00894-013-1898-5. PMID 23793719.

^ Music, D.; Geyer, R. W.; Schneider, J. M. (2016). "Recent progress and new directions in density functional theory based design of hard coatings". Surface & Coatings Technology. 286: 178–190. doi:10.1016/j.surfcoat.2015.12.021.

^ (Parr & Yang 1989, p. 47)

^ March, N. H. (1992). Electron Density Theory of Atoms and Molecules. Academic Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-12-470525-8.

^ Weizsäcker, C. F. v. (1935). "Zur Theorie der Kernmassen" [On the theory of nuclear masses]. Zeitschrift für Physik. 96 (7–8): 431–458. Bibcode:1935ZPhy...96..431W. doi:10.1007/BF01337700.

^ (Parr & Yang 1989, p. 127)

^ Topp, William C.; Hopfield, John J. (1973-02-15). "Chemically Motivated Pseudopotential for Sodium". Physical Review B. 7 (4): 1295–1303. Bibcode:1973PhRvB...7.1295T. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.7.1295.

^ Michelini, M. C.; Pis Diez, R.; Jubert, A. H. (25 June 1998). "A Density Functional Study of Small Nickel Clusters". International Journal of Quantum Chemistry. 70 (4–5): 694. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-461X(1998)70:4/5<693::AID-QUA15>3.0.CO;2-3.

^ "Finite temperature approaches – smearing methods". VASP the GUIDE. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

^ Tong, Lianheng. "Methfessel–Paxton Approximation to Step Function". Metal CONQUEST. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

Key papers

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Parr, R. G.; Yang, W. (1989). Density-Functional Theory of Atoms and Molecules. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-504279-5.

Thomas, L. H. (1927). "The calculation of atomic fields". Proc. Camb. Phil. Soc. 23 (5): 542–548. Bibcode:1927PCPS...23..542T. doi:10.1017/S0305004100011683.

Hohenberg, P.; Kohn, W. (1964). "Inhomogeneous Electron Gas". Physical Review. 136 (3B): B864. Bibcode:1964PhRv..136..864H. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.136.B864.

Kohn, W.; Sham, L. J. (1965). "Self-Consistent Equations Including Exchange and Correlation Effects". Physical Review. 140 (4A): A1133. Bibcode:1965PhRv..140.1133K. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.140.A1133.

Becke, Axel D. (1993). "Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 98 (7): 5648. Bibcode:1993JChPh..98.5648B. doi:10.1063/1.464913.

Lee, Chengteh; Yang, Weitao; Parr, Robert G. (1988). "Development of the Colle–Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density". Physical Review B. 37 (2): 785. Bibcode:1988PhRvB..37..785L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785.

Burke, Kieron; Werschnik, Jan; Gross, E. K. U. (2005). "Time-dependent density functional theory: Past, present, and future". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 123 (6): 062206. arXiv:cond-mat/0410362. Bibcode:2005JChPh.123f2206B. doi:10.1063/1.1904586. PMID 16122292.

Lejaeghere, K.; Bihlmayer, G.; Bjorkman, T.; Blaha, P.; Blugel, S.; Blum, V.; Caliste, D.; Castelli, I. E.; Clark, S. J.; Dal Corso, A.; de Gironcoli, S.; Deutsch, T.; Dewhurst, J. K.; Di Marco, I.; Draxl, C.; Du ak, M.; Eriksson, O.; Flores-Livas, J. A.; Garrity, K. F.; Genovese, L.; Giannozzi, P.; Giantomassi, M.; Goedecker, S.; Gonze, X.; Granas, O.; Gross, E. K. U.; Gulans, A.; Gygi, F.; Hamann, D. R.; Hasnip, P. J.; Holzwarth, N. A. W.; Iu an, D.; Jochym, D. B.; Jollet, F.; Jones, D.; Kresse, G.; Koepernik, K.; Kucukbenli, E.; Kvashnin, Y. O.; Locht, I. L. M.; Lubeck, S.; Marsman, M.; Marzari, N.; Nitzsche, U.; Nordstrom, L.; Ozaki, T.; Paulatto, L.; Pickard, C. J.; Poelmans, W.; Probert, M. I. J.; Refson, K.; Richter, M.; Rignanese, G.-M.; Saha, S.; Scheffler, M.; Schlipf, M.; Schwarz, K.; Sharma, S.; Tavazza, F.; Thunstrom, P.; Tkatchenko, A.; Torrent, M.; Vanderbilt, D.; van Setten, M. J.; Van Speybroeck, V.; Wills, J. M.; Yates, J. R.; Zhang, G.-X.; Cottenier, S. (2016). "Reproducibility in density functional theory calculations of solids". Science. 351 (6280): aad3000. Bibcode:2016Sci...351.....L. doi:10.1126/science.aad3000. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 27013736.

External links

Walter Kohn, Nobel Laureate Freeview video interview with Walter on his work developing density functional theory by the Vega Science Trust.

Capelle, Klaus (2002). "A bird's-eye view of density-functional theory". arXiv:cond-mat/0211443.

- Walter Kohn, Nobel Lecture

- Density functional theory on arxiv.org

- FreeScience Library -> Density Functional Theory

Argaman, Nathan; Makov, Guy (2000). "Density Functional Theory -- an introduction". American Journal of Physics. 68 (2000): 69–79. arXiv:physics/9806013. Bibcode:2000AmJPh..68...69A. doi:10.1119/1.19375.

- Electron Density Functional Theory – Lecture Notes

Density Functional Theory through Legendre Transformationpdf

Burke, Kieron. "The ABC of DFT" (PDF).

- Modeling Materials Continuum, Atomistic and Multiscale Techniques, Book

- NIST Jarvis-DFT

![{displaystyle {hat {H}}Psi =left[{hat {T}}+{hat {V}}+{hat {U}}right]Psi =left[sum _{i}^{N}left(-{frac {hbar ^{2}}{2m_{i}}}nabla _{i}^{2}right)+sum _{i}^{N}Vleft({vec {r}}_{i}right)+sum _{i<j}^{N}Uleft({vec {r}}_{i},{vec {r}}_{j}right)right]Psi =EPsi }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/dae1cf4d9b28b45caac87e9144609728bfb8fbbe)

![{displaystyle Psi _{0}=Psi [n_{0}]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fc26a8d11fb9a7208e1ca3c87ead3d107c361807)

![O[n_0] = leftlangle Psi[n_0] left| hat O right| Psi[n_0] rightrangle.](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/48cdc3fe972d03d3ce0afab8a93f9abbcba03f2e)

![E_0 = E[n_0] = leftlangle Psi[n_0] left| hat T + hat V + hat U right| Psi[n_0] rightrangle](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ee9c80c3d10e99d151916e0f534cdfe4e9db383e)

![{displaystyle V[n_{0}]=int Vleft({vec {r}}right)n_{0}left({vec {r}}right),{mathrm {d} }^{3}r.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/90a4e016cb679e8adb415f3ad301c5335ee681ff)

![{displaystyle V[n]=int V({vec {r}})n({vec {r}}),{mathrm {d} }^{3}r.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d300cc3838bd5ea6c7e9386e251b57d7a6a30677)

![{displaystyle E[n]=T[n]+U[n]+int V({vec {r}})n({vec {r}}),{mathrm {d} }^{3}r}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/98da89d850ac050fcab9794b0faad0fe3d26978b)

![{displaystyle E_{s}[n]=leftlangle Psi _{mathrm {s} }[n]left|{hat {T}}+{hat {V}}_{mathrm {s} }right|Psi _{mathrm {s} }[n]rightrangle }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e19631a5ca412367e9120c4fc00850f0c3402927)

![{displaystyle left[-{frac {hbar ^{2}}{2m}}nabla ^{2}+V_{mathrm {s} }({vec {r}})right]varphi _{i}({vec {r}})=varepsilon _{i}varphi _{i}({vec {r}})}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c806435acbf2ff03382efcb1426c010629926114)

![{displaystyle V_{mathrm {s} }({vec {r}})=V({vec {r}})+int {frac {e^{2}n_{mathrm {s} }left({vec {r}}'right)}{left|{vec {r}}-{vec {r}}'right|}},{mathrm {d} }^{3}r'+V_{mathrm {XC} }[n_{mathrm {s} }({vec {r}})]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d6567fd6ae18b5fec0ee4a2d09c128abd31f129c)

![{displaystyle E_{mathrm {XC} }^{mathrm {LDA} }[n]=int varepsilon _{mathrm {XC} }(n)n({vec {r}}),{mathrm {d} }^{3}r.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b333a8ca5b14701e3abec71a30df75fecc84cece)

![{displaystyle E_{mathrm {XC} }^{mathrm {LSDA} }left[n_{uparrow },n_{downarrow }right]=int varepsilon _{mathrm {XC} }left(n_{uparrow },n_{downarrow }right)n({vec {r}}),{mathrm {d} }^{3}r.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5a87e41be567ddef085347e9b7490554d4a0c942)

![{displaystyle E_{mathrm {XC} }^{mathrm {GGA} }left[n_{uparrow },n_{downarrow }right]=int varepsilon _{mathrm {XC} }left(n_{uparrow },n_{downarrow },nabla n_{uparrow },nabla n_{downarrow }right)n({vec {r}}),{mathrm {d} }^{3}r.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/db12214cac3c719e6658c936879fa90cb2e642ce)

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}t_{mathrm {TF} }[n]&={frac {p^{2}}{2m_{mathrm {e} }}}propto {frac {left(n^{frac {1}{3}}right)^{2}}{2m_{mathrm {e} }}}propto n^{frac {2}{3}}({vec {r}}),\[6pt]T_{mathrm {TF} }[n]&=C_{mathrm {F} }int n({vec {r}})n^{frac {2}{3}}({vec {r}}),mathrm {d} ^{3}r=C_{mathrm {F} }int n^{frac {5}{3}}({vec {r}}),mathrm {d} ^{3}r,end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d034b093167918555d8297e4d01a2d8ebb5a4628)

![{displaystyle T_{mathrm {W} }[n]={frac {hbar ^{2}}{8m}}int {frac {|nabla n({vec {r}})|^{2}}{n({vec {r}})}},mathrm {d} ^{3}r.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fcc9ab59273aa492d51bab26671c27a2be2bd281)

![{displaystyle E_{(v,N)}[n]=F[n]+int v({vec {r}})n({vec {r}}),mathrm {d} ^{3}r}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/39dcf84c92cbd21ac131622a0aa726bbb96a5cf2)

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}R_{l}^{mathrm {PP} }(r)&=R_{nl}^{mathrm {AE} }(r),\[6pt]int _{0}^{rl}left|R_{l}^{mathrm {PP} }(r)right|^{2}r^{2},mathrm {d} r&=int _{0}^{rl}left|R_{nl}^{mathrm {AE} }(r)right|^{2}r^{2},mathrm {d} r,end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c43d2f2fe9f1e02b96f8bdcc72b07316107a1eb4)

Comments

Post a Comment