Palestine (region)

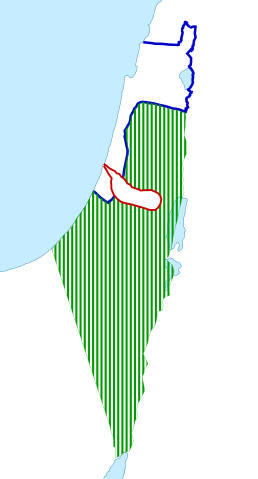

Boundaries of the Roman province Syria Palaestina, where dashed green line shows the boundary between Byzantine Palaestina Prima (later Jund Filastin) and Palaestina Secunda (later Jund al-Urdunn), as well as Palaestina Salutaris (later Jebel et-Tih and the Jifar)

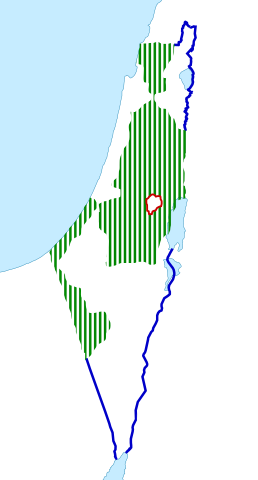

Borders of Mandatory Palestine

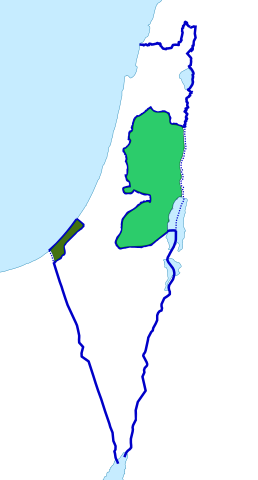

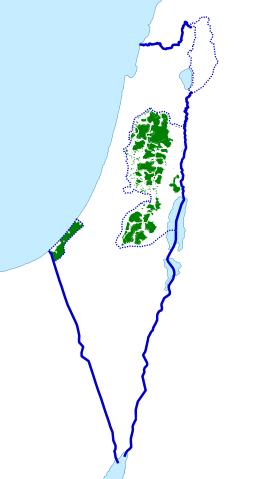

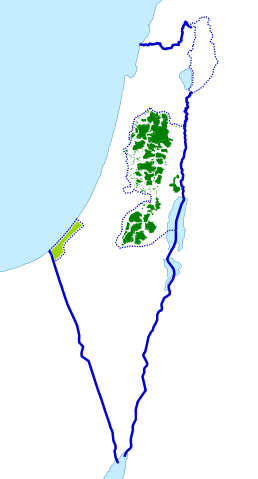

Borders of the Palestinian territories (West Bank and Gaza Strip) which are claimed by the State of Palestine as its borders

Palestine (Arabic: فلسطين Filasṭīn, Falasṭīn, Filisṭīn; Greek: Παλαιστίνη, Palaistinē; Latin: Palaestina; Hebrew: פלשתינה Palestina) is a geographic region in Western Asia usually considered to include Israel, the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, and in some definitions, some parts of western Jordan.

The name was used by ancient Greek writers, and it was later used for the Roman province Syria Palaestina, the Byzantine Palaestina Prima, and the Islamic provincial district of Jund Filastin. The region comprises most of the territory claimed for the biblical regions known as the Land of Israel (Hebrew: ארץ־ישראל Eretz-Yisra'el), the Holy Land or Promised Land. Historically, it has been known as the southern portion of wider regional designations such as Canaan, Syria, ash-Sham, and the Levant.

Situated at a strategic location between Egypt, Syria and Arabia, and the birthplace of Judaism and Christianity, the region has a long and tumultuous history as a crossroads for religion, culture, commerce, and politics. The region has been controlled by numerous peoples, including Ancient Egyptians, Canaanites, Israelites and Judeans, Assyrians, Babylonians, Achaemenids, ancient Greeks, the Jewish Hasmonean Kingdom, Romans, Parthians, Sasanians, Byzantines, the Arab Rashidun, Umayyad, Abbasid and Fatimid caliphates, Crusaders, Ayyubids, Mamluks, Mongols, Ottomans, the British, and modern Israelis, Jordanians, Egyptians and Palestinians.

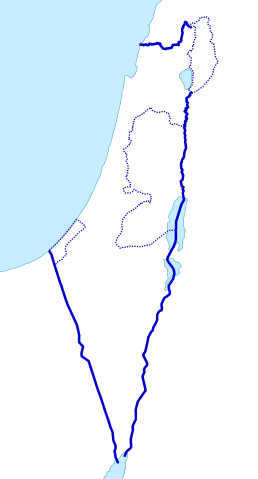

The boundaries of the region have changed throughout history. Today, the region comprises the State of Israel and the Palestinian territories in which the State of Palestine was declared.

Contents

1 History of the name

2 History

2.1 Overview

2.2 Ancient period

2.3 Classical antiquity

2.4 Middle Ages

2.5 Ottoman era

2.6 British mandate and partition

2.7 Post–1948

3 Boundaries

3.1 Ancient and Medieval

3.2 Modern period

3.3 Current usage

4 Demographics

4.1 Early demographics

4.2 Late Ottoman and British Mandate periods

4.3 Current demographics

5 Flora and fauna

5.1 Flora distribution

5.2 Birds

6 See also

7 Notes

8 References

9 Bibliography

History of the name

@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinner{width:100%!important;max-width:none!important}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{float:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center}}

Modern archaeology has identified 12 ancient inscriptions from Egyptian and Assyrian records recording likely cognates of Hebrew Pelesheth. The term "Peleset" (transliterated from hieroglyphs as P-r-s-t) is found in five inscriptions referring to a neighboring people or land starting from c. 1150 BCE during the Twentieth dynasty of Egypt. The first known mention is at the temple at Medinet Habu which refers to the Peleset among those who fought with Egypt in Ramesses III's reign,[1][2] and the last known is 300 years later on Padiiset's Statue. Seven known Assyrian inscriptions refer to the region of "Palashtu" or "Pilistu", beginning with Adad-nirari III in the Nimrud Slab in c. 800 BCE through to a treaty made by Esarhaddon more than a century later.[3][4] Neither the Egyptian nor the Assyrian sources provided clear regional boundaries for the term.[i]

The first clear use of the term Palestine to refer to the entire area between Phoenicia and Egypt was in 5th century BCE Ancient Greece,[7][8] when Herodotus wrote of a "district of Syria, called Palaistinê" (Ancient Greek: Συρίη ἡ Παλαιστίνη καλεομένη)[9] in The Histories, which included the Judean mountains and the Jordan Rift Valley.[10][ii] Approximately a century later, Aristotle used a similar definition for the region in Meteorology, in which he included the Dead Sea.[12] Later Greek writers such as Polemon and Pausanias also used the term to refer to the same region, which was followed by Roman writers such as Ovid, Tibullus, Pomponius Mela, Pliny the Elder, Dio Chrysostom, Statius, Plutarch as well as Roman Judean writers Philo of Alexandria and Josephus.[13][14] The term was first used to denote an official province in c. 135 CE, when the Roman authorities, following the suppression of the Bar Kokhba Revolt, combined Iudaea Province with Galilee and the Paralia to form "Syria Palaestina". There is circumstantial evidence linking Hadrian with the name change,[15] but the precise date is not certain[15] and the assertion of some scholars that the name change was intended "to complete the dissociation with Judaea"[16] is disputed.[17]

The term is generally accepted to be a translation of the Biblical name Peleshet (פלשת Pəlésheth, usually transliterated as Philistia). The term and its derivates are used more than 250 times in Masoretic-derived versions of the Hebrew Bible, of which 10 uses are in the Torah, with undefined boundaries, and almost 200 of the remaining references are in the Book of Judges and the Books of Samuel.[3][4][13][18] The term is rarely used in the Septuagint, which used a transliteration Land of Phylistieim (Γῆ τῶν Φυλιστιείμ) different from the contemporary Greek place name Palaistínē (Παλαιστίνη).[17]

The Septuagint instead used the term "allophuloi" (άλλόφυλοι, "other nations") throughout the Books of Judges and Samuel,[19][20] such that the term "Philistines" has been interpreted to mean "non-Israelites of the Promised Land" when used in the context of Samson, Saul and David,[21] and Rabbinic sources explain that these peoples were different from the Philistines of the Book of Genesis.[22]

During the Byzantine period, the region of Palestine within Syria Palaestina was subdivided into Palaestina Prima and Secunda,[23] and an area of land including the Negev and Sinai became Palaestina Salutaris.[23] Following the Muslim conquest, place names that were in use by the Byzantine administration generally continued to be used in Arabic.[3][24] The use of the name "Palestine" became common in Early Modern English,[25] was used in English and Arabic during the Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem[26][27][iii] and was revived as an official place name with the British Mandate for Palestine.

Some other terms that have been used to refer to all or part of this land include Canaan, Land of Israel (Eretz Yisrael or Ha'aretz),[29][iv] the Promised Land, Greater Syria, the Holy Land, Iudaea Province, Judea, Coele-Syria,[v] "Israel HaShlema", Kingdom of Israel, Kingdom of Jerusalem, Zion, Retenu (Ancient Egyptian), Southern Syria, Southern Levant and Syria Palaestina.

History

Overview

Situated at a strategic location between Egypt, Syria and Arabia, and the birthplace of Judaism and Christianity, the region has a long and tumultuous history as a crossroads for religion, culture, commerce, and politics. The region has been controlled by numerous peoples, including Ancient Egyptians, Canaanites, Israelites, Assyrians, Babylonians, Achaemenids, Ancient Greeks, Romans, Parthians, Sasanians, Byzantines, the Arab Rashidun, Umayyad, Abbasid and Fatimid caliphates, Crusaders, Ayyubids, Mamluks, Mongols, Ottomans, the British, and modern Israelis and Palestinians. Modern archaeologists and historians of the region refer to their field of study as Levantine archaeology.

Ancient period

Depiction of Biblical Palestine in c. 1020 BCE according to George Adam Smith's 1915 Atlas of the Historical Geography of the Holy Land. Smith's book was used as a reference by Lloyd George during the negotiations for the British Mandate for Palestine.[35]

The region was among the earliest in the world to see human habitation, agricultural communities and civilization.[36] During the Bronze Age, independent Canaanite city-states were established, and were influenced by the surrounding civilizations of ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Phoenicia, Minoan Crete, and Syria. Between 1550 and 1400 BCE, the Canaanite cities became vassals to the Egyptian New Kingdom who held power until the 1178 BCE Battle of Djahy (Canaan) during the wider Bronze Age collapse.[37] The Israelites emerged from a dramatic social transformation that took place in the people of the central hill country of Canaan around 1200 BCE, with no signs of violent invasion or even of peaceful infiltration of a clearly defined ethnic group from elsewhere.[38][39]

During the Iron Age the Israelites established two related kingdoms, Israel and Judah. The Kingdom of Israel emerged as an important local power by the 10th century BCE before falling to the Neo-Assyrian Empire in 722 BCE. Israel's southern neighbor, the Kingdom of Judah, emerged in the 8th or 9th century BCE and later became a client state of first the Neo-Assyrian and then the Neo-Babylonian Empire before a revolt against the latter led to its destruction in 586 BCE.

The region became part of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from c. 740 BCE,[40] which was itself replaced by the Neo-Babylonian Empire in c. 627 BCE.[41] According to the Bible, a war with Egypt culminated in 586 BCE when Jerusalem was destroyed by the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II and the king and upper class of the Kingdom of Judah were deported to Babylon. In 539 BCE, the Babylonian empire was replaced by the Achaemenid Empire. According to the Bible and implications from the Cyrus Cylinder, the exiled population of Judah was allowed to return to Jerusalem.[42] Southern Palestine became a province of the Achaemenid Empire, called Idumea, and the evidence from ostraca suggests that a Nabataean-type society, since the Idumeans appear to be connected to the Nabataeans, took shape in southern Palestine in the 4th century B.C.E., and that the Qedarite Arab kingdom penetrated throughout this area through the period of Persian and Hellenistic dominion.[43]

Classical antiquity

Herod's Temple in Jerusalem functioned as the spiritual center of the various sects of Second Temple Judaism until it was destroyed in 70 CE. This picture shows the temple as imagined in 1966 in the Holyland Model of Jerusalem.

In the 330s BCE, Macedonian ruler Alexander the Great conquered the region, which changed hands several times during the wars of the Diadochi and later Syrian Wars. It ultimately fell to the Seleucid Empire between 219–200 BCE. In 116 BCE, a Seleucid civil war resulted in the independence of certain regions including the Hasmonean principality in the Judaean Mountains.[44] From 110 BCE, the Hasmoneans extended their authority over much of Palestine, creating a Judaean–Samaritan–Idumaean–Ituraean–Galilean alliance.[45] The Judaean (Jewish, see Ioudaioi) control over the wider region resulted in it also becoming known as Judaea, a term that had previously only referred to the smaller region of the Judaean Mountains.[46][47] Between 73–63 BCE, the Roman Republic extended its influence into the region in the Third Mithridatic War, conquering Judea in 63 BCE, and splitting the former Hasmonean Kingdom into five districts. In around 40 BCE, the Parthians conquered Palestine, deposed the Roman ally Hyrcanus II, and installed a puppet ruler of the Hasmonean line known as Antigonus II.[48][49] By 37 BCE, the Parthians withdrew from Palestine.[48] The three-year Ministry of Jesus, culminating in his crucifixion, is estimated to have occurred from 28–30 CE, although the historicity of Jesus is disputed by a minority of scholars.[vi] In 70 CE, Titus sacked Jerusalem, resulting in the dispersal of the city's Jews and Christians to Yavne and Pella. In 132 CE, Hadrian joined the province of Iudaea with Galilee and the Paralia to form new province of Syria Palaestina, and Jerusalem was renamed "Aelia Capitolina". Between 259–272, the region fell under the rule of Odaenathus as King of the Palmyrene Empire. Following the victory of Christian emperor Constantine in the Civil wars of the Tetrarchy, the Christianization of the Roman Empire began, and in 326, Constantine's mother Saint Helena visited Jerusalem and began the construction of churches and shrines. Palestine became a center of Christianity, attracting numerous monks and religious scholars. The Samaritan Revolts during this period caused their near extinction. In 614 CE, Palestine was annexed by another Persian dynasty; the Sassanids, until returning to Byzantine control in 628 CE.[51]

Middle Ages

Palestine was conquered by the Islamic Caliphate, beginning in 634 CE.[52] In 636, the Battle of Yarmouk during the Muslim conquest of the Levant marked the start of Muslim hegemony over the region, which became known as Jund Filastin within the province of Bilâd al-Shâm (Greater Syria).[53] In 661, with the Assassination of Ali, Muawiyah I became the Caliph of the Islamic world after being crowned in Jerusalem.[54] The Dome of the Rock, completed in 691, was the world's first great work of Islamic architecture.[55]

The majority of the population was Christian and was to remain so until the conquest of Saladin in 1187. The Muslim conquest apparently had little impact on social and administrative continuities for several decades.[56][57][58][vii] The word 'Arab' at the time referred predominantly to Bedouin nomads, though Arab settlement is attested in the Judean highlands and near Jerusalem by the 5th century, and some tribes had converted to Christianity.[60] The local population engaged in farming, which was considered demeaning, and were called Nabaț, referring to Aramaic-speaking villagers. A ḥadīth, brought in the name of a Muslim freedman who settled in Palestine, ordered the Muslim Arabs not to settle in the villages, "for he who abides in villages it is as if he abides in graves".[61]

The Crusader fortress in Acre, also known as the Hospitaller Fortress, was built during the 12th century.

The Umayyads, who had spurred a strong economic resurgence in the area,[62] were replaced by the Abbasids in 750. Ramla became the administrative centre for the following centuries, while Tiberias became a thriving centre of Muslim scholarship.[63] From 878, Palestine was ruled from Egypt by semi-autonomous rulers for almost a century, beginning with the Turkish freeman Ahmad ibn Tulun, for whom both Jews and Christians prayed when he lay dying[64] and ending with the Ikhshidid rulers. Reverence for Jerusalem increased during this period, with many of the Egyptian rulers choosing to be buried there.[65] However, the later period became characterized by persecution of Christians as the threat from Byzantium grew.[66] The Fatimids, with a predominantly Berber army, conquered the region in 970, a date that marks the beginning of a period of unceasing warfare between numerous enemies, which destroyed Palestine, and in particular devastating its Jewish population.[67] Between 1071 and 1073, Palestine was captured by the Great Seljuq Empire,[68] only to be recaptured by the Fatimids in 1098,[69] who then lost the region to the Crusaders in 1099. The latter set up[70] the Kingdom of Jerusalem (1099-1291).[71] Their control of Jerusalem and most of Palestine lasted almost a century until their defeat by Saladin's forces in 1187,[72] after which most of Palestine was controlled by the Ayyubids,[72] except for the years 1229-1244 when Jerusalem and other areas were retaken[73] during the Sixth Crusade. A rump crusader state in the northern coastal cities survived until the end of the thirteenth century, but, despite seven further crusades, the Crusaders were no longer a significant power in the region.[74] The Fourth Crusade, which did not reach Palestine, led directly to the decline of the Byzantine Empire, dramatically reducing Christian influence throughout the region.[75]

The Mamluk Sultanate was indirectly created in Egypt as a result of the Seventh Crusade.[76] The Mongol Empire reached Palestine for the first time in 1260, beginning with the Mongol raids into Palestine under Nestorian Christian general Kitbuqa, and reaching an apex at the pivotal Battle of Ain Jalut, where they were routed by the Mamluks.[77]

Ottoman era

In 1486, hostilities broke out between the Mamluks and the Ottoman Empire in a battle for control over western Asia, and the Ottomans conquered Palestine in 1516.[78] Between the mid-16th and 17th centuries, a close-knit alliance of three local dynasties, the Ridwans of Gaza, the Turabays of al-Lajjun and the Farrukhs of Nablus, governed Palestine on behalf of the Porte (imperial Ottoman government).[79]

The Khan al-Umdan, constructed in Acre in 1784, is the largest and best preserved caravanserai in the region.

In the 18th century, the Zaydani clan under the leadership of Zahir al-Umar ruled large parts of Palestine autonomously[80] until the Ottomans were able to defeat them in their Galilee strongholds in 1775-76.[81] Zahir had turned the port city of Acre into a major regional power, partly fueled by his monopolization of the cotton and olive oil trade from Palestine to Europe. Acre's regional dominance was further elevated under Zahir's successor Ahmad Pasha al-Jazzar at the expense of Damascus.[82]

In 1830, on the eve of Muhammad Ali's invasion,[83] the Porte transferred control of the sanjaks of Jerusalem and Nablus to Abdullah Pasha, the governor of Acre. According to Silverburg, in regional and cultural terms this move was important for creating an Arab Palestine detached from greater Syria (bilad al-Sham).[84] According to Pappe, it was an attempt to reinforce the Syrian front in face of Muhammad Ali's invasion.[85] Two years later, Palestine was conquered by Muhammad Ali's Egypt,[83] but Egyptian rule was challenged in 1834 by a countrywide popular uprising against conscription and other measures considered intrusive by the population.[86] Its suppression devastated many of Palestine's villages and major towns.[87]

In 1840, Britain intervened and returned control of the Levant to the Ottomans in return for further capitulations.[88] The death of Aqil Agha marked the last local challenge to Ottoman centralization in Palestine,[89] and beginning in the 1860s, Palestine underwent an acceleration in its socio-economic development, due to its incorporation into the global, and particularly European, economic pattern of growth. The beneficiaries of this process were Arabic-speaking Muslims and Christians who emerged as a new layer within the Arab elite.[90] From 1880 large-scale Jewish immigration began, almost entirely from Europe, based on an explicitly Zionist ideology.[91] There was also a revival of the Hebrew language and culture.[92]

Christian Zionism in the United Kingdom preceded its spread within the Jewish community.[93] The government of Great Britain publicly supported it during World War I with the Balfour Declaration of 1917.[94]

British mandate and partition

Palestine passport and Palestine coin. The Mandatory authorities agreed a compromise position regarding the Hebrew name: in English and Arabic the name was simply "Palestine" ("فلسطين"), but the Hebrew version "(פלשתינה)" also included the acronym "(א״י)" for Eretz Yisrael (Land of Israel).

The new era in Palestine. The arrival of Herbert Samuel as the first High Commissioner for Palestine in 1920. Samuel had promoted Zionism within the British Cabinet, beginning with his 1915 memorandum entitled The Future of Palestine. Beside him are Lawrence of Arabia, Emir Abdullah, Air Marshal Salmond and Wyndham Deedes.

The British began their Sinai and Palestine Campaign in 1915.[95] The war reached southern Palestine in 1917, progressing to Gaza and around Jerusalem by the end of the year.[95] The British secured Jerusalem in December 1917.[96] They moved into the Jordan valley in 1918 and a campaign by the Entente into northern Palestine led to victory at Megiddo in September.[96]

The British were formally awarded the mandate to govern the region in 1922.[97] The non-Jewish Palestinians revolted in 1920, 1929, and 1936.[98] In 1947, following World War II and The Holocaust, the British Government announced its desire to terminate the Mandate, and the United Nations General Assembly adopted in November 1947 a Resolution 181(II) recommending partition into an Arab state, a Jewish state and the Special International Regime for the City of Jerusalem.[99] The Jewish leadership accepted the proposal, but the Arab Higher Committee rejected it; a civil war began immediately after the Resolution's adoption. The State of Israel was declared in May 1948.[100]

Post–1948

In the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, Israel captured and incorporated a further 26% of the Mandate territory, Jordan captured the region of Judea and Samaria,[101][102][103] renaming it the "West Bank", while the Gaza Strip was captured by Egypt.[104][105] Following the 1948 Palestinian exodus, also known as al-Nakba, the 700,000 Palestinians who fled or were driven from their homes were not allowed to return following the Lausanne Conference of 1949.[106]

In the course of the Six-Day War in June 1967, Israel captured the rest of Mandate Palestine from Jordan and Egypt, and began a policy of establishing Jewish settlements in those territories. From 1987 to 1993, the First Palestinian Intifada against Israel took place, which included the Declaration of the State of Palestine in 1988 and ended with the 1993 Oslo Peace Accords and the creation of the Palestinian National Authority.

In 2000, the Second Intifada (also called al-Aqsa Intifada) began, and Israel built a separation barrier. In the 2005 Israeli disengagement from Gaza, Israel withdrew all settlers and military presence from the Gaza Strip, but maintained military control of numerous aspects of the territory including its borders, air space and coast. Israel's ongoing military occupation of the Gaza Strip, the West Bank and East Jerusalem continues to be the world's longest military occupation in modern times.[viii][ix]

In November 2012, the status of Palestinian delegation in the United Nations was upgraded to non-member observer state as the State of Palestine.[117][x]

Boundaries

Satellite image of the region of Palestine, 2003.

Ancient and Medieval

The boundaries of Palestine have varied throughout history.[xi][xii] The Jordan Rift Valley (comprising Wadi Arabah, the Dead Sea and River Jordan) has at times formed a political and administrative frontier, even within empires that have controlled both territories.[120] At other times, such as during certain periods during the Hasmonean and Crusader states for example, as well as during the biblical period, territories on both sides of the river formed part of the same administrative unit. During the Arab Caliphate period, parts of southern Lebanon and the northern highland areas of Palestine and Jordan were administered as Jund al-Urdun, while the southern parts of the latter two formed part of Jund Dimashq, which during the 9th century was attached to the administrative unit of Jund Filastin.[121]

The boundaries of the area and the ethnic nature of the people referred to by Herodotus in the 5th century BCE as Palaestina vary according to context. Sometimes, he uses it to refer to the coast north of Mount Carmel. Elsewhere, distinguishing the Syrians in Palestine from the Phoenicians, he refers to their land as extending down all the coast from Phoenicia to Egypt.[122]Pliny, writing in Latin in the 1st century CE, describes a region of Syria that was "formerly called Palaestina" among the areas of the Eastern Mediterranean.[123]

Since the Byzantine Period, the Byzantine borders of Palaestina (I and II, also known as Palaestina Prima, "First Palestine", and Palaestina Secunda, "Second Palestine"), have served as a name for the geographic area between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea. Under Arab rule, Filastin (or Jund Filastin) was used administratively to refer to what was under the Byzantines Palaestina Secunda (comprising Judaea and Samaria), while Palaestina Prima (comprising the Galilee region) was renamed Urdunn ("Jordan" or Jund al-Urdunn).[3]

Modern period

Nineteenth-century sources refer to Palestine as extending from the sea to the caravan route, presumably the Hejaz-Damascus route east of the Jordan River valley.[124] Others refer to it as extending from the sea to the desert.[124] Prior to the Allied Powers victory in World War I and the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire, which created the British mandate in the Levant, most of the northern area of what is today Jordan formed part of the Ottoman Vilayet of Damascus (Syria), while the southern part of Jordan was part of the Vilayet of Hejaz.[125] What later became Mandatory Palestine was in late Ottoman times divided between the Vilayet of Beirut (Lebanon) and the Sanjak of Jerusalem.[28] The Zionist Organization provided its definition of the boundaries of Palestine in a statement to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919.[126][127]

The British administered Mandatory Palestine after World War I, having promised to establish a homeland for the Jewish people. The modern definition of the region follows the boundaries of that entity, which were fixed in the North and East in 1920-23 by the British Mandate for Palestine (including the Transjordan memorandum) and the Paulet–Newcombe Agreement,[29] and on the South by following the 1906 Turco-Egyptian boundary agreement.[128][129]

1916–1922 proposals: Three proposals for the post World War I administration of Palestine. The red line is the "International Administration" proposed in the 1916 Sykes–Picot Agreement, the dashed blue line is the 1919 Zionist Organization proposal at the Paris Peace Conference, and the thin blue line refers to the final borders of the 1923–48 Mandatory Palestine.

1937 proposal: The first official proposal for partition, published in 1937 by the Peel Commission. An ongoing British Mandate was proposed to keep "the sanctity of Jerusalem and Bethlehem", in the form of an enclave from Jerusalem to Jaffa, including Lydda and Ramle.

1947 (proposal): Proposal per the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine (UN General Assembly Resolution 181 (II), 1947), prior to the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. The proposal included a Corpus Separatum for Jerusalem, extraterritorial crossroads between the non-contiguous areas, and Jaffa as an Arab exclave.

1947 (actual): Mandatory Palestine, showing Jewish-owned regions in Palestine as of 1947 in blue, constituting 6% of the total land area, of which more than half was held by the JNF and PICA. The Jewish population had increased from 83,790 in 1922 to 608,000 in 1946.

1948–1967 (actual): The Jordanian-annexed West Bank (light green) and Egyptian-occupied Gaza Strip (dark green), after the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, showing 1949 armistice lines.

1967–1994: During the Six-Day War, Israel captured the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, and the Golan Heights, together with the Sinai Peninsula (later traded for peace after the Yom Kippur War). In 1980–81 Israel annexed East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights.

Neither Israel's annexation nor Palestine's claim over East Jerusalem has been internationally recognized.

1994–2006: Under the Oslo Accords, the Palestinian National Authority was created to provide civil government in certain urban areas of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

2006–present: After the Israeli disengagement from Gaza and clashes between the two main Palestinian parties following the Hamas electoral victory, two separate executive governments took control in Gaza and the West Bank.

Current usage

The region of Palestine is the eponym for the Palestinian people and the culture of Palestine, both of which are defined as relating to the whole historical region, usually defined as the localities within the border of Mandatory Palestine. The 1968 Palestinian National Covenant described Palestine as the "homeland of the Arab Palestinian people", with "the boundaries it had during the British Mandate".[130]

However, since the 1988 Palestinian Declaration of Independence, the term State of Palestine refers only to the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. This discrepancy was described by the Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas as a negotiated concession in a September 2011 speech to the United Nations: "... we agreed to establish the State of Palestine on only 22% of the territory of historical Palestine - on all the Palestinian Territory occupied by Israel in 1967."[131]

The term Palestine is also sometimes used in a limited sense to refer to the parts of the Palestinian territories currently under the administrative control of the Palestinian National Authority, a quasi-governmental entity which governs parts of the State of Palestine under the terms of the Oslo Accords.[xiii]

Demographics

Early demographics

| Year | Jews | Christians | Muslims | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First half 1st century CE | Majority | – | – | ~2,500 | ||

| 5th century | Minority | Majority | – | >1st C | ||

| End 12th century | Minority | Minority | Majority | >225 | ||

| 14th century before Black Death | Minority | Minority | Majority | 225 | ||

| 14th century after Black Death | Minority | Minority | Majority | 150 | ||

| Historical population table compiled by Sergio DellaPergola.[133] Figures in thousands. | ||||||

Estimating the population of Palestine in antiquity relies on two methods – censuses and writings made at the times, and the scientific method based on excavations and statistical methods that consider the number of settlements at the particular age, area of each settlement, density factor for each settlement.

The Bar Kokhba revolt in the 2nd century CE saw a major shift in the population of Palestine. The sheer scale and scope of the overall destruction has been described by Dio Cassius in his Roman History, where he notes that Roman war operations in the country had left some 580,000 Jews dead, with many more dying of hunger and disease, while 50 of their most important outposts and 985 of their most famous villages were razed to the ground. "Thus," writes Dio Cassius, "nearly the whole of Judaea was made desolate."[134][135]

According to Israeli archaeologists Magen Broshi and Yigal Shiloh, the population of ancient Palestine did not exceed one million.[136][137] By 300 CE, Christianity had spread so significantly that Jews comprised only a quarter of the population.[72]

Late Ottoman and British Mandate periods

In a study of Ottoman registers of the early Ottoman rule of Palestine, Bernard Lewis reports:

[T]he first half century of Ottoman rule brought a sharp increase in population. The towns grew rapidly, villages became larger and more numerous, and there was an extensive development of agriculture, industry, and trade. The two last were certamly helped to no small extent by the influx of Spanish and other Western Jews.

From the mass of detail in the registers, it is possible to extract something like a general picture of the economic life of the country in that period. Out of a total population of about 300,000 souls, between a fifth and a quarter lived in the six towns of Jerusalem, Gaza, Safed, Nablus, Ramle, and Hebron. The remainder consisted mainly of peasants, living in villages of varying size, and engaged in agriculture. Their main food-crops were wheat and barley in that order, supplemented by leguminous pulses, olives, fruit, and vegetables. In and around most of the towns there was a considerable number of vineyards, orchards, and vegetable gardens.[138]:487

| Year | Jews | Christians | Muslims | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1533–1539 | 5 | 6 | 145 | 157 | ||

| 1690–1691 | 2 | 11 | 219 | 232 | ||

| 1800 | 7 | 22 | 246 | 275 | ||

| 1890 | 43 | 57 | 432 | 532 | ||

| 1914 | 94 | 70 | 525 | 689 | ||

| 1922 | 84 | 71 | 589 | 752 | ||

| 1931 | 175 | 89 | 760 | 1,033 | ||

| 1947 | 630 | 143 | 1,181 | 1,970 | ||

| Historical population table compiled by Sergio DellaPergola.[133] Figures in thousands. | ||||||

According to Alexander Scholch, the population of Palestine in 1850 was about 350,000 inhabitants, 30% of whom lived in 13 towns; roughly 85% were Muslims, 11% were Christians and 4% Jews.[139]

According to Ottoman statistics studied by Justin McCarthy, the population of Palestine in the early 19th century was 350,000, in 1860 it was 411,000 and in 1900 about 600,000 of whom 94% were Arabs.[140] In 1914 Palestine had a population of 657,000 Muslim Arabs, 81,000 Christian Arabs, and 59,000 Jews.[141] McCarthy estimates the non-Jewish population of Palestine at 452,789 in 1882; 737,389 in 1914; 725,507 in 1922; 880,746 in 1931; and 1,339,763 in 1946.[142]

In 1920, the League of Nations' Interim Report on the Civil Administration of Palestine described the 700,000 people living in Palestine as follows:[143]

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

Of these, 235,000 live in the larger towns, 465,000 in the smaller towns and villages. Four-fifths of the whole population are Moslems. A small proportion of these are Bedouin Arabs; the remainder, although they speak Arabic and are termed Arabs, are largely of mixed race. Some 77,000 of the population are Christians, in large majority belonging to the Orthodox Church, and speaking Arabic. The minority are members of the Latin or of the Uniate Greek Catholic Church, or—a small number—are Protestants.

The Jewish element of the population numbers 76,000. Almost all have entered Palestine during the last 40 years. Prior to 1850, there were in the country only a handful of Jews. In the following 30 years, a few hundreds came to Palestine. Most of them were animated by religious motives; they came to pray and to die in the Holy Land, and to be buried in its soil. After the persecutions in Russia forty years ago, the movement of the Jews to Palestine assumed larger proportions.

Current demographics

According to the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, as of 2015[update], the total population of Israel was 8.5 million people, of which 75% were Jews, 21% Arabs, and 4% "others."[144] Of the Jewish group, 76% were Sabras (born in Israel); the rest were olim (immigrants)—16% from Europe, the former Soviet republics, and the Americas, and 8% from Asia and Africa, including the Arab countries.[145]

According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics evaluations, in 2015 the Palestinian population of the West Bank was approximately 2.9 million and that of the Gaza Strip was 1.8 million.[146] Gaza's population is expected to increase to 2.1 million people in 2020, leading to a density of more than 5,800 people per square kilometre.[147]

Both Israeli and Palestinian statistics include Arab residents of East Jerusalem in their reports.[148] According to these estimates the total population in the region of Palestine, as defined as Israel and the Palestinian territories, stands approximately 12.8 million.

Flora and fauna

Flora distribution

The World Geographical Scheme for Recording Plant Distributions is widely used in recording the distribution of plants. The scheme uses the code "PAL" to refer to the region of Palestine – a Level 3 area. The WGSRPD's Palestine is further divided into Israel (PAL-IS), including the Palestinian territories, and Jordan (PAL-JO), so is larger than some other definitions of "Palestine".[149]

Birds

See also

- Palestine Exploration Fund

- Place names of Palestine

Levantine archaeology (a.k.a. Palestinian archaeology)

Notes

^ Eberhard Schrader wrote in his seminal "Keilinschriften und Geschichtsforschung" ("KGF", in English "Cuneiform inscriptions and Historical Research") that the Assyrian tern "Palashtu" or "Pilistu" referred to the wider Palestine or "the East" in general, instead of "Philistia".[5][6]

^ In The Histories, Herodotus referred to the practice of male circumcision associated with the Hebrew people: "the Colchians, the Egyptians, and the Ethiopians, are the only nations who have practised circumcision from the earliest times. The Phoenicians and the Syrians of Palestine themselves confess that they learnt the custom of the Egyptians.... Now these are the only nations who use circumcision."[11]

^ For example, the 1915 Filastin Risalesi ("Palestine Document"), an Ottoman army (VIII Corps (Ottoman Empire)) country survey which formally identified Palestine as including the sanjaqs of Akka (the Galilee), the Sanjaq of Nablus, and the Sanjaq of Jerusalem (Kudus Sherif)[28]

^ The New Testament, taking up a term used once in the Tanakh (1 Samuel 13:19),[30][31] speaks of a larger theologically-defined area, of which Palestine is a part, as the "land of Israel"[32] (γῆ Ἰσραήλ) (Matthew 2:20–21), in a narrative paralleling that of the Book of Exodus.[33]

^ Other writers, such as Strabo, referred to the region as Coele-Syria ("all Syria") around 10–20 CE.[34]

^ For example, in a 2011 review of the state of modern scholarship, Bart Ehrman (a secular agnostic) described the dispute, whilst concluding: "He certainly existed, as virtually every competent scholar of antiquity, Christian or non-Christian, agrees"[50]

^ The earlier view, exemplifed by the writings of Moshe Gil, argued for a Jewish-Samaritan majority at the time of conquest: "We may reasonably state that at the time if the Muslim conquest, a large Jewish population still lived in Palestine. We do not know whether they formed the majority but we may assume with some certainly that they did so when grouped together with the Samaritans."[59]

^ The majority of the international community (including the UN General Assembly, the United Nations Security Council, the European Union, the International Criminal Court, and the vast majority of human rights organizations) considers Israel to be continuing to occupying Gaza, the West Bank and East Jerusalem. The government of Israel and some supporters have, at times, disputed this position of the international community. In 2011, Andrew Sanger explained the situation as follows: "Israel claims it no longer occupies the Gaza Strip, maintaining that it is neither a Stale nor a territory occupied or controlled by Israel, but rather it has 'sui generis' status. Pursuant to the Disengagement Plan, Israel dismantled all military institutions and settlements in Gaza and there is no longer a permanent Israeli military or civilian presence in the territory. However the Plan also provided that Israel will guard and monitor the external land perimeter of the Gaza Strip, will continue to maintain exclusive authority in Gaza air space, and will continue to exercise security activity in the sea off the coast of the Gaza Strip as well as maintaining an Israeli military presence on the Egyptian-Gaza border. and reserving the right to reenter Gaza at will. Israel continues to control six of Gaza's seven land crossings, its maritime borders and airspace and the movement of goods and persons in and out of the territory. Egypt controls one of Gaza's land crossings. Troops from the Israeli Defence Force regularly enter pans of the territory and/or deploy missile attacks, drones and sonic bombs into Gaza. Israel has declared a no-go buffer zone that stretches deep into Gaza: if Gazans enter this zone they are shot on sight. Gaza is also dependent on israel for inter alia electricity, currency, telephone networks, issuing IDs, and permits to enter and leave the territory. Israel also has sole control of the Palestinian Population Registry through which the Israeli Army regulates who is classified as a Palestinian and who is a Gazan or West Banker. Since 2000 aside from a limited number of exceptions Israel has refused to add people to the Palestinian Population Registry. It is this direct external control over Gaza and indirect control over life within Gaza that has led the United Nations, the UN General Assembly, the UN Fact Finding Mission to Gaza, International human rights organisations, US Government websites, the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office and a significant number of legal commentators, to reject the argument that Gaza is no longer occupied.",[107] and in 2012 Iain Scobbie explained: "Even after the accession to power of Hamas, Israel's claim that it no longer occupies Gaza has not been accepted by UN bodies, most States, nor the majority of academic commentators because of its exclusive control of its border with Gaza and crossing points including the effective control it exerted over the Rafah crossing until at least May 2011, its control of Gaza's maritime zones and airspace which constitute what Aronson terms the 'security envelope' around Gaza, as well as its ability to intervene forcibly at will in Gaza"[108] and Michelle Gawerc wrote in the same year: "While Israel withdrew from the immediate territory, Israel still controlled all access to and from Gaza through the border crossings, as well as through the coastline and the airspace. ln addition, Gaza was dependent upon Israel for water electricity sewage communication networks and for its trade (Gisha 2007. Dowty 2008). ln other words, while Israel maintained that its occupation of Gaza ended with its unilateral disengagement Palestinians - as well as many human right organizations and international bodies - argued that Gaza was by all intents and purposes still occupied."[109]

For more details of this terminology dispute, including with respect to the current status of the Gaza Strip, see International views on the Israeli-occupied territories and Status of territories captured by Israel.

^ For an explanation of the differences between an annexed but disputed territory (e.g. Tibet) and a militarily occupied territory, please see the article Military occupation. The "longest military occupation" description has been described in a number of ways, including: "The Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza is the longest military occupation in modern times,"[110] "...longest official military occupation of modern history—currently entering its thirty-fifth year,"[111] "...longest-lasting military occupation of the modern age, "[112] "This is probably the longest occupation in modern international relations, and it holds a central place in all literature on the law of belligerent occupation since the early 1970s,"[113] "These are settlements and a military occupation that is the longest in the twentieth and twenty-first century, the longest formerly being the Japanese occupation of Korea from 1910 to 1945. So this is thirty-three years old [in 2000], pushing the record,"[114] "Israel is the only modern state that has held territories under military occupation for over four decades."[115] In 2014 Sharon Weill provided further context, writing: "Although the basic philosophy behind the law of military occupation is that it is a temporary situation modem occupations have well demonstrated that rien ne dure comme le provisoire A significant number of post-1945 occupations have lasted more than two decades such as the occupations of Namibia by South Africa and of East Timor by Indonesia as well as the ongoing occupations of Northern Cyprus by Turkey and of Western Sahara by Morocco. The Israeli occupation of the Palestinian territories, which is the longest in all occupation's history has already entered its fifth decade."[116]

^ See United Nations General Assembly resolution 67/19 for further details

^ According to the Jewish Encyclopedia published between 1901 and 1906:[118] "Palestine extends, from 31° to 33° 20′ N. latitude. Its southwest point (at Raphia, Tell Rifaḥ, southwest of Gaza) is about 34° 15′ E. longitude, and its northwest point (mouth of the Liṭani) is at 35° 15′ E. longitude, while the course of the Jordan reaches 35° 35′ to the east. The west-Jordan country has, consequently, a length of about 150 English miles from north to south, and a breadth of about 23 miles (37 km) at the north and 80 miles (129 km) at the south. The area of this region, as measured by the surveyors of the English Palestine Exploration Fund, is about 6,040 square miles (15,644 km2). The east-Jordan district is now being surveyed by the German Palästina-Verein, and although the work is not yet completed, its area may be estimated at 4,000 square miles (10,360 km2). This entire region, as stated above, was not occupied exclusively by the Israelites, for the plain along the coast in the south belonged to the Philistines, and that in the north to the Phoenicians, while in the east-Jordan country, the Israelitic possessions never extended farther than the Arnon (Wadi al-Mujib) in the south, nor did the Israelites ever settle in the most northerly and easterly portions of the plain of Bashan. To-day the number of inhabitants does not exceed 650,000. Palestine, and especially the Israelitic state, covered, therefore, a very small area, approximating that of the state of Vermont." From the Jewish Encyclopedia

^ According to the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition (1911), Palestine is:[119] "[A] geographical name of rather loose application. Etymological strictness would require it to denote exclusively the narrow strip of coast-land once occupied by the Philistines, from whose name it is derived. It is, however, conventionally used as a name for the territory which, in the Old Testament, is claimed as the inheritance of the pre-exilic Hebrews; thus it may be said generally to denote the southern third of the province of Syria. Except in the west, where the country is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea, the limit of this territory cannot be laid down on the map as a definite line. The modern subdivisions under the jurisdiction of the Ottoman Empire are in no sense conterminous with those of antiquity, and hence do not afford a boundary by which Palestine can be separated exactly from the rest of Syria in the north, or from the Sinaitic and Arabian deserts in the south and east; nor are the records of ancient boundaries sufficiently full and definite to make possible the complete demarcation of the country. Even the convention above referred to is inexact: it includes the Philistine territory, claimed but never settled by the Hebrews, and excludes the outlying parts of the large area claimed in Num. xxxiv. as the Hebrew possession (from the " River of Egypt " to Hamath). However, the Hebrews themselves have preserved, in the proverbial expression " from Dan to Beersheba " (Judg. xx.i, &c.), an indication of the normal north-and-south limits of their land; and in defining the area of the country under discussion it is this indication which is generally followed. Taking as a guide the natural features most nearly corresponding to these outlying points, we may describe Palestine as the strip of land extending along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea from the mouth of the Litany or Kasimiya River (33° 20' N.) southward to the mouth of the Wadi Ghuzza; the latter joins the sea in 31° 28' N., a short distance south of Gaza, and runs thence in a south-easterly direction so as to include on its northern side the site of Beersheba. Eastward there is no such definite border. The River Jordan, it is true, marks a line of delimitation between Western and Eastern Palestine; but it is practically impossible to say where the latter ends and the Arabian desert begins. Perhaps the line of the pilgrim road from Damascus to Mecca is the most convenient possible boundary. The total length of the region is about 140 m (459.32 ft); its breadth west of the Jordan ranges from about 23 m (75.46 ft) in the north to about 80 m (262.47 ft) in the south."

^ See for example, Palestinian school textbooks[132]

References

^ Fahlbusch et al. 2005, p. 185.

^ Breasted 2001, p. 24.

^ abcd Sharon 1988, p. 4.

^ ab Room 2006, p. 285

^ Schrader 1878, p. 123-124.

^ Anspacher 1912, p. 48.

^ Jacobson 1999: "The earliest occurrence of this name in a Greek text is in the mid-fifth century b.c., Histories of Herodotus, where it is applied to the area of the Levant between Phoenicia and Egypt."..."The first known occurrence of the Greek word Palaistine is in the Histories of Herodotus, written near the mid-fifth century B.C. Palaistine Syria, or simply Palaistine, is applied to what may be identified as the southern part of Syria, comprising the region between Phoenicia and Egypt. Although some of Herodotus' references to Palestine are compatible with a narrow definition of the coastal strip of the Land of Israel, it is clear that Herodotus does call the "whole land by the name of the coastal strip."..."It is believed that Herodotus visited Palestine in the fifth decade of the fifth century B.C."..."In the earliest Classical literature references to Palestine generally applied to the Land of Israel in the wider sense."

^ Jacobson 2001: "As early as the Histories of Herodotus, written in the second half of the fifth century B.C.E., the term Palaistinê is used to describe not just the geographical area where the Philistines lived, but the entire area between Phoenicia and Egypt—in other words, the Land of Israel. Herodotus, who had traveled through the area, would have had firsthand knowledge of the land and its people. Yet he used Palaistinê to refer not to the Land of the Philistines, but to the Land of Israel"

^ Herodotus- Histories Book 3 Chapter 91

^ Jacobson 1999, p. 65.

^ Herodotus 1858, p. Bk ii, Ch 104.

^ Jacobson 1999, p. 66-67.

^ ab Robinson, 1865, p.15: "Palestine, or Palestina, now the most common name for the Holy Land, occurs three times in the English version of the Old Testament; and is there put for the Hebrew name פלשת, elsewhere rendered Philistia. As thus used, it refers strictly and only to the country of the Philistines, in the southwest corner of the land. So, too, in the Greek form, Παλαςτίνη), it is used by Josephus. But both Josephus and Philo apply the name to the whole land of the Hebrews ; and Greek and Roman writers employed it in the like extent."

^ Louis H. Feldman, whose view differs from that of Robinson, thinks that Josephus, when referring to Palestine, had in mind only the coastal region, writing: "Writers on geography in the first century [CE] clearly differentiate Judaea from Palestine. ...Jewish writers, notably Philo and Josephus, with few exceptions refer to the land as Judaea, reserving the name Palestine for the coastal area occupied [formerly] by the Philistines." (END QUOTE). See: p. 1 in: Feldman, Louis (1990). "Some Observations on the Name of Palestine". Hebrew Union College Annual. 61: 1–23. JSTOR 23508170..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}.

^ ab Feldman 1996, p. 553.

^ Sharon 1988, p. 4a:"Eager to obliterate the name of the rebellious Judaea, the Roman authorities (General Hadrian) renamed it Palaestina or Syria Palaestina."

^ ab Jacobson 1999, p. 72-74.

^ Lewis, 1993, p. 153.

^ Jobling & Rose 1996, p. 404a.

^ Drews 1998, p. 49: "Our names ‘Philistia’ and ‘Philistines’ are unfortunate obfuscations, first introduced by the translators of the LXX and made definitive by Jerome’s Vg. When turning a Hebrew text into Greek, the translators of the LXX might simply—as Josephus was later to do—have Hellenized the Hebrew פְּלִשְׁתִּים as Παλαιστίνοι, and the toponym פְּלִשְׁתִּ as Παλαιστίνη. Instead, they avoided the toponym altogether, turning it into an ethnonym. As for the ethnonym, they chose sometimes to transliterate it (incorrectly aspirating the initial letter, perhaps to compensate for their inability to aspirate the sigma) as φυλιστιιμ, a word that looked exotic rather than familiar, and more often to translate it as άλλόφυλοι. Jerome followed the LXX’s lead in eradicating the names, ‘Palestine’ and ‘Palestinians’, from his Old Testament, a practice adopted in most modern translations of the Bible."

^ Drews 1998, p. 51: "The LXX’s regular translation of פְּלִשְׁתִּים into άλλόφυλοι is significant here. Not a proper name at all, allophyloi is a generic term, meaning something like ‘people of other stock’. If we assume, as I think we must, that with their word allophyloi the translators of the LXX tried to convey in Greek what p'lištîm had conveyed in Hebrew, we must conclude that for the worshippers of Yahweh p'lištîm and b'nê yiśrā'ēl were mutually exclusive terms, p'lištîm (or allophyloi) being tantamount to ‘non-Judaeans of the Promised Land’ when used in a context of the third century BCE, and to ‘non-Israelites of the Promised Land’ when used in a context of Samson, Saul and David. Unlike an ethnonym, the noun פְּלִשְׁתִּים normally appeared without a definite article."

^ Jobling & Rose 1996, p. 404: "Rabbinic sources insist that the Philistines of Judges and Samuel were different people altogether from the Philistines of Genesis. (Midrash Tehillim on Psalm 60 (Braude: vol. 1, 513); the issue here is precisely whether Israel should have been obliged, later, to keep the Genesis treaty.) This parallels a shift in the Septuagint's translation of Hebrew pelistim. Before Judges, it uses the neutral transliteration phulistiim, but beginning with Judges it switches to the pejorative allophuloi. [To be precise, Codex Alexandrinus starts using the new translation at the beginning of Judges and uses it invariably thereafter, Vaticanus likewise switches at the beginning of Judges, but reverts to phulistiim on six occasions later in Judges, the last of which is 14:2.]"

^ ab Kaegi 1995, p. 41.

^ Marshall Cavendish, 2007, p. 559.

^ Krämer 2011, p. 16.

^ Büssow 2011, p. 5.

^ Abu-Manneh 1999, p. 39.

^ ab Tamari 2011, pp. 29–30: "Filastin Risalesi, is the salnameh type military handbook issued for Palestine at the beginning of the Great War... The first is a general map of the country in which the boundaries extend far beyond the frontiers of the Mutasarflik of Jerusalem, which was, until then, the standard delineation of Palestine. The northern borders of this map include the city of Tyre (Sur) and the Litani River, thus encompassing all of the Galilee and parts of southern Lebanon, as well as districts of Nablus, Haifa and Akka—all of which were part of the Wilayat of Beirut until the end of the war."

^ ab Biger 2004, p. 133, 159.

^ Whitelam 1996, p. 40-42.

^ Masalha 2007, p. 32.

^ Saldarini 1994, p. 28-29.

^ Goldberg 2001, p. 147: “The parallels between this narrative and that of Exodus continue to be drawn. Like Pharaoh before him, Herod, having been frustrated in his original efforts, now seeks to achieve his objectives by implementing a program of infanticide. As a result, here - as in Exodus - rescuing the hero’s life from the clutches of the evil king necessitates a sudden flight to another country. And finally, in perhaps the most vivid parallel of all, the present narrative uses virtually the same words of the earlier one to provide the information that the coast is clear for the herds safe return: here, in Matthew 2:20, "go [back]… for those who sought the child's life are dead; there, in Exodus 4:19, go back… for all the men who sought your life are dead.”

^ Feldman 1996, p. 557-8.

^ Grief 2008, p. 33.

^ Ahlström 1993, p. 72-111.

^ Ahlström 1993, p. 282-334.

^ Finkelstein and Silberman, 2001, p 107

^ Krämer 2011, p. 8: "Several scholars hold the revisionist thesis that the Israelites did not move to the area as a distinct and foreign ethnic group at all, bringing with them their god Yahwe and forcibly evicting the indigenous population, but that they gradually evolved out of an amalgam of several ethnic groups, and that the Israelite cult developed on "Palestinian" soil amid the indigenous population. This would make the Israelites "Palestinians" not just in geographical and political terms (under the British Mandate, both Jews and Arabs living in the country were defined as Palestinians), but in ethnic and broader cultural terms as well. While this does not conform to the conventional view, or to the understanding of most Jews (and Arabs, for that matter), it is not easy to either prove or disprove. For although the Bible speaks at length about how the Israelites "took" the land, it is not a history book to draw reliable maps from. There is nothing in the extra-biblical sources, including the extensive Egyptian materials, to document the sojourn in Egypt or the exodus so vividly described in the Bible (and commonly dated to the thirteenth century). Biblical scholar Moshe Weinfeld sees the biblical account of the exodus, and of Moses and Joshua as founding heroes of the "national narration," as a later rendering of a lived experience that was subsequently either "forgotten" or consciously repressed -- a textbook case of the "invented tradition" so familiar to modern students of ethnicity and nationalism."

^ Crouch, C. L. (1 October 2014). Israel and the Assyrians: Deuteronomy, the Succession Treaty of Esarhaddon, and the Nature of Subversion. SBL Press. ISBN 978-1-62837-026-3.Judah's reason(s) for submitting to Assyrian hegemony, at least superficially, require explanation, while at the same time indications of its read-but-disguised resistance to Assyria must be uncovered... The political and military sprawl of the Assyrian empire during the late Iron Age in the southern Levant, especially toward its outer borders, is not quite akin to the single dominating hegemony envisioned by most discussions of hegemony and subversion. In the case of Judah it should be reiterated that Judah was always a vassal state, semi-autonomous and on the periphery of the imperial system, it was never a fully-integrated provincial territory. The implications of this distinction for Judah's relationship with and experience of the Assyrian empire should not be underestimated; studies of the expression of Assyria's cultural and political powers in its provincial territories and vassal states have revealed notable differences in the degree of active involvement in different types of territories. Indeed, the mechanics of the Assyrian empire were hardly designed for direct control over all its vassals' internal activities, provided that a vassal produced the requisite tribute and did not provoke trouble among its neighbors, the level of direct involvement from Assyria remained relatively low. For the entirety of its experience of the Assyrian empire, Judah functioned as a vassal state, rather than a province under direct Assyrian rule, thereby preserving at least a certain degree of autonomy, especially in its internal affairs. Meanwhile, the general atmosphere of Pax Assyriaca in the southern Levant minimized the necessity of (and opportunities for) external conflict. That Assyrians, at least in small numbers, were present in Judah is likely - probably a qipu and his entourage who, if the recent excavators of Ramat Rahel are correct, perhaps resided just outside the capital - but there is far less evidence than is commonly assumed to suggest that these left a direct impression of Assyria on this small vassal state... The point here is that, despite the wider context of Assyria's political and economic power in the ancient Near East in general and the southern Levant in particular, Judah remained a distinguishable and semi-independent southern Levantine state, part of but not subsumed by the Assyrian empire and, indeed, benefitting from it in significant ways.

^ Ahlström 1993, p. 655-741, 754-784.

^ Ahlström 1993, p. 804-890.

^ David F. Graf, 'Petra and the Nabataeans in the Early Hellenistic Period: the literary and archaeological evidence,' in Michel Mouton, Stephan G. Schmid (eds.), Men on the Rocks: The Formation of Nabataean Petra, Logos Verlag Berlin GmbH, 2013 pp.35-55 pp.47-48:'the Idumean textgs indicate that a large portion of the community in southern Palestine were Arabs, many of whom have names similar to those in the "Nabataean"onomasticon of later periods.' (p.47).

^ Smith 1999, p. 215.

^ Smith 1999, p. 210.

^ Smith 1999, p. 210a: "In both the Idumaean and the Ituraean alliances, and in the annexation of Samaria, the Judaeans had taken the leading role. They retained it. The whole political–military–religious league that now united the hill country of Palestine from Dan to Beersheba, whatever it called itself, was directed by, and soon came to be called by others, 'the Ioudaioi'"

^ Ben-Sasson, p.226, "The name Judea no longer referred only to...."

^ ab Neusner 1983, p. 911.

^ Vermes 2014, p. 36.

^ Ehrman, 2011, page 285

^ Greatrex-Lieu (2002), II, 196

^ Gil 1997, p. i.

^ Gil 1997, p. 47.

^ Gil 1997, p. 76.

^ Brown, 2011, p. 122: 'the first great Islamic architectural achievement.'

^ Avni 2014, p. 314,336.

^ Flusin 2011, p. 199-226, 215: "The religious situation also evolved under the new masters. Christianity did remain the majority religion, but it lost the privileges it had enjoyed."

^ O'Mahony, 2003, p. 14: ‘Before the Muslim conquest, the population of Palestine was overwhelmingly Christian, albeit with a sizeable Jewish community.’

^ Gil 1997, p. 3.

^ Avni 2014, p. 154-55.

^ Gil 1997, p. 134-136.

^ Walmsley, 2000, pp. 265-343, p. 290

^ Gil 1997, p. 329.

^ Gil 1997, p. 306ff. and p. 307 n. 71; p. 308 n. 73.

^ Bianquis 1998, p. 103: “Under the Tulunids, Syro-Egyptian territory was deeply imbued with the concept of an extraordinary role devolving upon Jerusalem in Islam as al-Quds, Bayt al-Maqdis or Bayt al-Muqaddas, the “House of Holiness”, the seat of the Last Judgment, the Gate to Paradise for Muslims as well as for Jews and Christians. In the popular conscience, this concept established a bond between the three monotheistic religions. If Ahmad ibn Tulun was interred on the slope of the Muqattam, Isa ibn Musa al-Nashari and Takin were laid to rest in Jerusalem in 910 and 933, as were their Ikhshidid successors and Kafir. To honor the great general and governor of Syria Anushtakin al-Dizbiri, who died in 433/1042, the Fatimid Dynasty had his remains solemnly conveyed from Aleppo to Jerusalem in 448/1056-57.”

^ Gil 1997, p. 324.

^ Gil 1997, p. 336.

^ Gil 1997, p. 410.

^ Gil 1997, p. 209, 414.

^ Christopher Tyerman, God's War: A New History of the Crusades (Penguin: 2006), pp. 201-202

^ Gil 1997, p. 826.

^ abc Krämer 2011, p. 15.

^ Adrian J. Boas (2001). Jerusalem in the Time of the Crusades: Society, Landscape and Art in the Holy City Under Frankish Rule. London: Routledge. pp. 19–20. ISBN 9780415230001. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

^ Setton 1969, p. 615-621 (vol. 1).

^ Setton 1969, p. 152-185 (vol. 2).

^ Setton 1969, p. 486-518 (vol. 2).

^ Krämer 2011, p. 35-39.

^ Krämer 2011, p. 40.

^ Zeevi 1996, p. 45.

^ Phillipp 2013, pp. 42-43.

^ Joudah 1987, pp. 115-117.

^ Burns 2005, p. 246.

^ ab Krämer 2011, p. 64.

^ Silverburg, 2009, pp. 9–36, p. 29 n. 32.

^ Pappe 1999, p. 38.

^ Kimmerling & Migdal 2003, pp. 7-8.

^ Kimmerling & Migdal 2003, p. 11.

^ Krämer 2011, p. 71.

^ Yazbak 1998, p. 3.

^ Gilbar 1986, p. 188.

^ "1st Aliyah to Israel". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

^ Krämer 2011, p. 120: "In 1914 about 12,000 Jewish farmers and fieldworkers lived in approximately forty Jewish settlements -- and to repeat it once again, they were by no means all Zionists. The dominant languages were still Yiddish, Russian, Polish, Rumanian, Hungarian, or German in the case of Ashkenazi immigrants from Europe, and Ladino (or "Judeo-Spanish") and Arabic in the case of Sephardic and Oriental Jews. Biblical Hebrew served as the sacred language, while modern Hebrew (Ivrit) remained for the time being the language of a politically committed minority that had devoted itself to a revival of "Hebrew culture."

^ Shapira, Anita (2014). Israel a history, translated from Hebrew by Anthony Berris. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 15. ISBN 9781611683523.

^ Krämer 2011, p. 148.

^ ab Morris 2001, p. 67.

^ ab Morris 2001, p. 67-120.

^ Segev 2001, p. 270-294.

^ Segev 2001, p. 1-13.

^ Segev 2001, p. 468-487.

^ Segev 2001, p. 487-521.

^ Pappé 1994, p. 119 "His (Abdallah) natural choice was the regions of Judea and Samaria...".

^ Spencer C. Tucker, Priscilla Roberts 2008, p. 248—249, 500, 522... "Transjordan, however, controlled large portions of Judea and Samaria, later known as the West Bank".

^ Gerson 2012, p. 93 "Trans-Jordan was also in control of all of Judea and Samaria (the West Bank)".

^ Pappé 1994, p. 102-135.

^ Khalidi 2007, p. 12-36.

^ Pappé 1994, p. 87-101 and 203-243.

^ Sanger 2011, p. 429.

^ Scobbie 2012, p. 295.

^ Gawerc 2012, p. 44.

^ Hajjar 2005, p. 96.

^ Anderson 2001.

^ Makdisi 2010, p. 299.

^ Kretzmer 2012, p. 885.

^ Said 2003, p. 33.

^ Alexandrowicz 2012.

^ Weill 2014, p. 22.

^ "General Assembly Votes Overwhelmingly to Accord Palestine 'Non-Member Observer State' Status in United Nations". United Nations. 2012.

^ JE 1906.

^ EB 1911.

^ Yohanan Aharoni (1 January 1979). The Land of the Bible: A Historical Geography. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-664-24266-4.The desert served as an eastern boundary in times when Transjordan was occupied. But when Transjordan became an unsettled region, a pasturage for desert nomads, then the Jordan Valley and the Dead Sea formed the natural eastern boundary of Western Palestine.

^ Salibi 1993, p. 17-18.

^ Herodotus 1858, p. Bk vii, Ch 89.

^ Pliny, Natural History V.66 and 68.

^ ab Biger 2004, p. 19-20.

^ Biger 2004, p. 13.

^ Tessler 1994, p. 163.

^ Biger 2004, p. 41-80.

^ Biger 2004, p. 80.

^ Kliot 1995, p. 9.

^ Said & Hitchens 2001, p. 199.

^ "Full transcript of Abbas speech at UN General Assembly". Haaretz.com. 23 September 2011.

^ Adwan 2006, p. 242: "The term Palestine in the textbooks refers to Palestinian National Authority."

^ ab DellaPergola 2001, p. 5.

^ Dio's Roman History (trans. Earnest Cary), vol. 8 (books 61–70), Loeb Classical Library: London 1925, pp. 449–451

^ Taylor, Joan E. The Essenes, the Scrolls, and the Dead Sea. Oxford University Press.Up until this date the Bar Kokhba documents indicate that towns, villages and ports where Jews lived were busy with industry and activity. Afterwards there is an eerie silence, and the archaeological record testifies to little Jewish presence until the Byzantine era, in En Gedi. This picture coheres with what we have already determined in Part I of this study, that the crucial date for what can only be described as genocide, and the devastation of Jews and Judaism within central Judea, was 135 CE and not, as usually assumed, 70 CE, despite the siege of Jerusalem and the Temple's destruction

ISBN 978-0-19-955448-5

^ Broshi 1979, p. 7: "... the population of Palestine in antiquity did not exceed a million persons. It can also be shown, moreover, that this was more or less the size of the population in the peak period—the late Byzantine period, around AD 600"

^ Shiloh 1980, p. 33: "... the population of the country in the Roman-Byzantine period greatly exceeded that in the Iron Age... If we accept Broshi's population estimates, which appear to be confirmed by the results of recent research, it follows that the estimates for the population during the Iron Age must be set at a lower figure."

^ Lewis 1954, p. 469-501.

^ Scholch 1985, p. 503.

^ McCarthy 1990, p. 26.

^ McCarthy 1990, p. 30.

^ McCarthy 1990, p. 37–38.

^ Kirk, 2011, p.46

^ "Population, by Population Group". Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

^ "Jews, by Continent of Origin, Continent of Birth & Period of Immigration". Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

^ "Estimated Population in the Palestinian Territory Mid-Year by Governorate, 1997-2016". Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

^ UN News Centre 2012.

^ Mezzofiore, Gianluca (2 January 2015). "Will Palestinians outnumber Israeli Jews by 2016?". International Business Times. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

^ Brummitt, R.K. (2001). World Geographical Scheme for Recording Plant Distributions: Edition 2 (PDF). International Working Group on Taxonomic Databases For Plant Sciences (TDWG). Archived from the original on 25 January 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2016.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maps of the history of the Middle East. |

Wikisource has original text related to this article: Palestine |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Palestine (region) |

- Abu-Lughod, Ibrahim (1971) (ed.) The Transformation of Palestine. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern Press

Abu-Manneh, Butrus (1999). "The Rise of the Sanjak of Jerusalem in the Late Nineteenth Century". In Ilan Pappé. The Israel/Palestine Question. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-16948-6. Retrieved 2013-06-28.

Adwan, Sami (2006). "Textbooks in the Palestinian National Authority". In Charles W. Greenbaum; Philip E. Veerman; Naomi Bacon-Shnoor. Protection of Children During Armed Political Conflict: A Multidisciplinary Perspective. Intersentia. p. 231–256. ISBN 9789050953412.

Ahlström, Gösta Werner (1993). The history of ancient Palestine. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8006-2770-6.

Alexandrowicz, Ra'anan (2012), The Justice of Occupation, The New York Times

Anderson, Perry (2001). "Editorial: Scurrying Towards Bethlehem". New Left Review. 10.

Anspacher, Abraham Samuel (1912). Tiglath Pileser III.

- Avneri, Arieh (1984) The Claim of Dispossession. Tel Aviv: Hidekel Press

Avni, Gideon (2014). The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199684335.

- Bachi, Roberto (1974) The Population of Israel. Jerusalem: Institute of Contemporary Jewry, Hebrew University

- Belfer-Cohen, Anna & Bar-Yosef, Ofer (2000) "Early Sedentism in the Near East: a bumpy ride to village life". In: Ian Kuijt (Ed.) Life in Neolithic Farming Communities: social organization, identity, and differentiation. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers

ISBN 0-306-46122-6

- Ben-Sasson, Haim Hillel (1976), A History of the Jewish People, Harvard University Press

Biger, Gideon (2004). The Boundaries of Modern Palestine, 1840–1947. RoutledgeCurzon. passim. ISBN 9781135766528.

- Biger, Gideon (1981) "Where was Palestine? pre-World War I perception", in: AREA (journal of the Institute of British Geographers); Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 153–160

Breasted, James Henry (2001). Ancient Records of Egypt: The first through the seventeenth dynasties. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-06990-0.

Broshi, Magen (1979). "The Population of Western Palestine in the Roman-Byzantine Period". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (236).

- Brown, Daniel W. (2011), A New Introduction to Islam, Wiley-Blackwell, 2nd.ed.

Büssow, Johann (2011). Hamidian Palestine: Politics and Society in the District of Jerusalem 1872-1908. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-20569-7. Retrieved 2013-05-17.

Burns, Ross (2005). Damascus: A History. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-27105-3..- Byatt, Anthony (1973) "Josephus and Population Numbers in First-century Palestine", in: Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 105, pp. 51–60.

- Chancey, Mark A. (2005) Greco-Roman Culture and the Galilee of Jesus. Cambridge University Press

ISBN 0-521-84647-1

- Chase, Kenneth (2003) Firearms: a Global History to 1700. Cambridge University Press

ISBN 0-521-82274-2

Bianquis, Thierry (1998). "Autonomous Egypt from Ibn Tulun to Kafur 868-969". In Martin W. Daly; Carl F. Petry. The Cambridge History of Egypt, Volume 2. Cambridge University Press. pp. 86–119. ISBN 9780521471374.

DellaPergola, Sergio (2001), "Demography in Israel/Palestine: Trends, Prospects, Policy Implications" (PDF), IUSSP XXIVth General Population Conference in Salvador de Bahia, Brazil, 18–24 August 2001

- Doumani, Beshara (1995) Rediscovering Palestine: merchants and peasants in Jabal Nablus 1700–1900. Berkeley: University of California Press

ISBN 0-520-20370-4

Drews, Robert (1998), "Canaanites and Philistines", Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, 81: 39–61

- B. Ehrman, 2011 Forged : writing in the name of God

ISBN 978-0-06-207863-6

Ember, Melvin; Peregrine, Peter Neal, eds. (2001). Encyclopedia of Prehistory. 8 : South and Southwest Asia (1 ed.). New York and London: Springer. p. 185. ISBN 0-306-46262-1.

Fahlbusch, Erwin; Lochman, Jan Milic; Bromiley, Geoffrey William; Barrett, David B. (2005). The encyclopedia of Christianity. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 9780802824165.

- Farsoun, Samih K. & Naseer Aruri (2006) Palestine and the Palestinians; 2nd ed. Boulder CO: Westview Press

ISBN 0-8133-4336-4

Feldman, Louis H. (1996) [1990]. "Some Observations on the Name of Palestine". Studies in Hellenistic Judaism. Leiden: Brill. pp. 553–576. ISBN 9789004104181. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- Finkelstein, I., Mazar, A. & Schmidt, B. (2007) The Quest for the Historical Israel. Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature

ISBN 978-1-58983-277-0

- Finkelstein, Israel, and Silberman, Neil Asher, The Bible Unearthed : Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts, Simon & Schuster, 2002.

ISBN 0-684-86912-8

Flusin, Bernard (2011). "Palestinia Hagiography (Fourth-Eighth Centuries)". In Stephanos Efthymiadis. The Ashgate Research Companion to Byzantine Hagiography. 1. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9780754650331.

Gawerc, Michelle (2012). Prefiguring Peace: Israeli-Palestinian Peacebuilding Partnerships. Lexington Books. p. 44. ISBN 9780739166109.

- Gelber, Yoav (1997) Jewish-Transjordanian Relations 1921–48: alliance of bars sinister. London: Routledge

ISBN 0-7146-4675-X

- Gerber, Haim (1998) "Palestine" and Other Territorial Concepts in the 17th Century", in: International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol 30, pp. 563–572.

Gerson, Allan (2012). Israel, the West Bank and International Law. Routledge. p. 285. ISBN 0714630918.

Gil, Moshe (1997). A History of Palestine, 634–1099. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521599849.

Gilbar, Gar G. (1986). "The Growing Economic Involvement of Palestine with the West, 1865–1914". In David Kushner (ed.). Palestine in the Late Ottoman Period: political, social and economic transformation. Brill Academic Publishers. pp. 188–210. ISBN 90-04-07792-8.CS1 maint: Extra text: editors list (link)

- Gilbar, Gar G. (ed.) (1990) Ottoman Palestine: 1800–1914: studies in economic and social history. Leiden: Brill

ISBN 90-04-07785-5

Gilbert, Martin (2005) The Routledge Atlas of the Arab-Israeli Conflict. London: Routledge

ISBN 0-415-35900-7

Goldberg, Michael (2001). Jews and Christians: Getting Our Stories Straight. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 9781579107765.

- Gottheil, Fred M. (2003) "The Smoking Gun: Arab immigration into Palestine, 1922–1931, Middle East Quarterly, X (1)

Grief, Howard (2008). The Legal Foundation and Borders of Israel Under International Law. Mazo Publishers. ISBN 9789657344521. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

Grisanti, Michael A.; Howard, David M. (2003). Giving the Sense: understanding and using Old Testament historical texts (Illustrated ed.). Kregel Publications. ISBN 9780825428920.

Hajjar, Lisa (2005). Courting Conflict: The Israeli Military Court System in the West Bank and Gaza. University of California Press. p. 96. ISBN 0520241940.

- Hansen, Mogens Herman (ed.) (2000) A Comparative Study of Thirty City-state Cultures: an investigation. Copenhagen: Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskab

ISBN 87-7876-177-8

- Harris, David Russell (1996) The Origins and Spread of Agriculture and Pastoralism in Eurasia. London: Routledge.

ISBN 1-85728-537-9

- Hayes, John H. & Mandell, Sara R. (1998) The Jewish People in Classical Antiquity: from Alexander to Bar Kochba. Louisville KY: Westminster John Knox Press

ISBN 0-664-25727-5

Herodotus (1858). George Rawlinson, ed. The Histories, full text of all books (Book I to Book IX).

- Hughes, Mark (1999) Allenby and British Strategy in the Middle East, 1917–1919. London: Routledge

ISBN 0-7146-4920-1

- Ingrams, Doreen (1972) Palestine Papers 1917–1922. London: John Murray

ISBN 0-8076-0648-0

Kaegi, Walter Emil (1995). Byzantium and the Early Islamic Conquests (Reprint, illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521484558.

Jacobson, David (1999). "Palestine and Israel". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. JSTOR 1357617.

Jacobson, David (2001), "When Palestine Meant Israel", Biblical Archaeology Review, 27 (3)