Neo-Babylonian Empire

Neo-Babylonian Empire | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 626 BC–539 BC | |||||||||

The Neo-Babylonian Empire at its greatest extent of power | |||||||||

| Capital | Babylon, Tayma (it was the de facto capital of Neo-Babylon under Nabonidus)[1] | ||||||||

| Common languages | Akkadian, Aramaic | ||||||||

| Religion | Babylonian religion | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

• 626–605 BC | Nabopolassar (first) | ||||||||

• 556–539 BC | Nabonidus (last) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Babylonian Revolt | 626 BC | ||||||||

• Battle of Opis | 539 BC | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Iraq |

|

Prehistory |

|

Bronze Age |

|

Iron Age |

|

Middle Ages |

|

Early modern period |

|

Modern Iraq |

|

The Neo-Babylonian Empire (also Second Babylonian Empire) was a period of Mesopotamian history which began in 626 BC and ended in 539 BC.[2] During the preceding three centuries, Babylonia had been ruled by their fellow Akkadian speakers and northern neighbours, Assyria. A year after the death of the last strong Assyrian ruler, Ashurbanipal, in 627 BC, the Assyrian empire spiralled into a series of brutal civil wars. Babylonia rebelled under Nabopolassar. In alliance with the Medes, Persians, Scythians and Cimmerians, they sacked the city of Nineveh in 612 BC,[3] and the seat of empire was transferred to Babylonia for the first time since the death of Hammurabi in the mid-18th century BC. This period witnessed a general improvement in economic life and agricultural production, and a great flourishing of architectural projects, the arts and science.

The Neo-Babylonian period ended with the reign of Nabonidus in 539 BC. To the east, the Persians had been growing in strength, and eventually Cyrus the Great conquered the empire.

Contents

1 Historical background

1.1 Revival of old traditions

1.2 Cultural and economic life

2 Neo-Babylonian dynasty

2.1 Nabopolassar 626–605 BC

2.2 Nebuchadnezzar II 605–562 BC

2.3 Amel-Marduk 562–560 BC

2.4 Neriglissar 560–556 BC

2.5 Labashi-Marduk 556 BC

2.6 Nabonidus 556–539 BC

3 Fall of Babylon

4 See also

5 References

Historical background

Babylonia was subject to and dominated by Assyria during the Neo-Assyrian period (911–626 BC), as it had often been during the Middle Assyrian Empire (1365–1020 BC). The Assyrians of Upper Mesopotamia had usually been able to pacify their southern relations through military might, installing puppet kings, or granting increased privileges.

Revival of old traditions

After Babylonia regained its independence, Neo-Babylonian rulers were deeply conscious of the antiquity of their kingdom and pursued an archtraditionalist policy, reviving much of the ancient Sumero-Akkadian culture. Even though Aramaic had become the everyday tongue, Akkadian was retained as the language of administration and culture. Archaic expressions from 1500 years earlier were reintroduced in Akkadian inscriptions, along with words in the long-unspoken Sumerian language. Neo-Babylonian cuneiform script was also modified to make it look like the old 3rd-millennium BC script of Akkad.

Ancient artworks from the heyday of Babylonia's imperial glory were treated with near-religious reverence and were painstakingly preserved. For example, when a statue of Sargon the Great was found during construction work, a temple was built for it, and it was given offerings. The story is told of how Nebuchadnezzar II, in his efforts to restore the Temple at Sippar, had to make repeated excavations until he found the foundation deposit of Naram-Sin of Akkad. The discovery then allowed him to rebuild the temple properly. Neo-Babylonians also revived the ancient Sargonid practice of appointing a royal daughter to serve as priestess of the moon-god Sîn.

Cultural and economic life

Much more is known about Mesopotamian culture and economic life under the Neo-Babylonians than about the structure and mechanics of imperial administration. It is clear that for southern Mesopotamia, the Neo-Babylonian period was a renaissance. Large tracts of land were opened to cultivation. Peace and imperial power made resources available to expand the irrigation systems and to build an extensive canal system. The Babylonian countryside was dominated by large estates, which were given to government officials as a form of pay. The estates were usually managed by local entrepreneurs, who took a cut of the profits. Rural folk were bound to these estates, providing both labour and rents to their landowners.

Urban life flourished under the Neo-Babylonians. Cities had local autonomy and received special privileges from the kings. Centered on their temples, the cities had their own law courts, and cases were often decided in assemblies. Temples dominated urban social structure, just as they did the legal system, and a person's social status and political rights were determined by where they stood in relation to the religious hierarchy. Free laborers like craftsmen enjoyed high status and a sort of guild system came into existence, which gave them collective bargaining power. The period witnessed a general improvement in economic life, agricultural production, and a significant increase in architectural projects, the arts and science.

Neo-Babylonian dynasty

Dynasty XI of Babylon (Neo-Babylonian)

Nabu-apla-usur 626–605 BC

Nabu-kudurri-usur II 605–562 BC

Amel-Marduk 562–560 BC

Neriglissar 560–556 BC

Labaši- Marduk 556 BC

Nabonidus 556–539 BC

Nabopolassar 626–605 BC

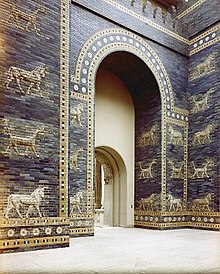

The Ishtar Gate of Babylon as reconstructed in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin

After the death of Ashurbanipal in 627 BC, the Assyrian Empire began to disintegrate, riven by internal strife. Ashur-etil-ilani co-ruled with Ashurbanipal from 630 BC, while an Assyrian governor named Kandalanu sat on the throne of Babylon on behalf of his king. Babylonia seemed secure until both Ashurbanipal and Kandalanu died in 627 BC, and Assyria spiralled into a series of internal civil wars which would ultimately lead to its destruction. An Assyrian general, Sin-shumu-lishir, revolted in 626 BC and declared himself king of Assyria and Babylon, but was promptly ousted by the Assyrian Army loyal to king Ashur-etil-ilani in 625 BC. Babylon was then taken by another son of Ashurbanipal Sin-shar-ishkun, who proclaimed himself king. His rule did not last long, however, and the Babylonians revolted. Nabopolassar seized the throne amid the confusion, and the Neo-Babylonian dynasty was born. Babylonia as a whole then became a battleground between king Ashur-etil-ilani and his brother Sin-shar-ishkun who fought to and fro over the region. This anarchic situation allowed Nabopolassar to stay on the throne of the city of Babylon itself, spending the next three years undisturbed, consolidating his position in the city.[4]

However, in 623 BC, Sin-shar-ishkun killed his brother the king in battle at Nippur in Babylonia, seized the throne of Assyria, and then set about retaking Babylon from Nabopolassar. Nabopolassar was forced to endure Assyrian armies encamped in Babylonia over the next seven years. However, he resisted, aided by the continuing civil war in Assyria itself, which greatly hampered Sin-shar-ishkun's attempts to retake the parts of Babylonia held by Nabopolassar. Nabopolassar took Nippur in 619 BC, a key centre of pro-Assyrianism in Babylonia, and by 616 BC, he was still in control of much of southern Mesopotamia. Assyria, still riven with internal strife, had by this time lost control of its colonies, who had taken advantage of the various upheavals to free themselves. The empire had stretched from Cyprus to Persia and the Caucasus to Egypt at its height.

Nabopolassar attempted a counterattack; he marched his army into Assyria proper in 616 BC and tried to besiege Assur and Arrapha (Kirkuk), but was defeated by Sin-shar-ishkun and driven back into Babylonia. A stalemate seemed to have ensued, with Nabopolassar unable to make any inroads into Assyria despite its greatly weakened state, and Sin-shar-ishkun unable to eject Nabopolassar from Babylon due to the unremitting civil war in Assyria itself.

However the balance of power was decisively tipped when Cyaxares, ruler of the Iranian peoples (the Medes, Persians and Parthians), and technically a vassal of Assyria, attacked a war-weary Assyria without warning in late 615 BC, sacking Arrapha and Kalhu (the biblical Nimrud). Then in 614 BC Cyaxares, in alliance with the Scythians and Cimmerians, besieged and took Assur, with Nabopolassar remaining uninvolved in these successes.[5]

Nabopolassar too then made active alliances with other former subjects of Assyria; the Medes, Persians, Scythians and Cimmerians.

During 613 BC the Assyrian army seems to have rallied and successfully repelled Babylonian, Median and Scythian attacks. However, in 612 BC Nabopolassar and the Median king Cyaxares led a concentrated coalition of forces including Babylonians, Chaldeans, Medes, Persians, Scythians and Cimmerians in an attack on Nineveh. The size of the forces ranged against Assyria in its weakened state proved too much, and, after a bitter three-month siege, followed by house-to-house fighting, Nineveh finally fell, with Sin-shar-ishkun being killed defending his capital.

An Assyrian general, Ashur-uballit II, became king of Assyria amid the fighting. According to the Babylonian Chronicle, he was offered the chance to bow in vassalage to the rulers of the alliance. However, he refused, and managed to fight his way free of Nineveh to set up a new capital at Harran. Nabopolassar, Cyaxares, and their allies, then fought Ashur-uballit II for a further five years, until Harran fell in 608 BC; after a failed attempt to retake the city, Ashur-uballit II disappeared from the pages of history.

The Egyptians under Pharaoh Necho II had invaded the near east in 609 BC in a belated attempt to help their former Assyrian rulers. Nabopolassar (with the help of his son and future successor Nebuchadnezzar II) spent the last years of his reign dislodging the Egyptians (who were supported by Greek mercenaries and the remnants of the Assyrian army) from Syria, Asia Minor, northern Arabia and Israel. Nebuchadnezzar proved to be a capable and energetic military leader, and the Egyptians, Assyrians and their mercenary allies were finally defeated by the Babylonians, Medes and Scythians at the Battle of Carchemish in 605 BC.

The Babylonians were now left in possession of much of Assyria, with the northern reaches being held by the Medes. However, they appear to have made no attempt to occupy it, preferring to concentrate on rebuilding southern Mesopotamia.

Nebuchadnezzar II 605–562 BC

An engraving on an eye stone of onyx with an inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II

Nebuchadnezzar II became king after the death of his father.

Nebuchadnezzar was a patron of the cities and a spectacular builder. He rebuilt all of Babylonia's major cities on a lavish scale. His building activity at Babylon was what turned it into the immense and beautiful city of legend. His city of Babylon covered more than three square miles, surrounded by moats and ringed by a double circuit of walls. The Euphrates flowed through the center of the city, spanned by a beautiful stone bridge. At the center of the city rose the giant ziggurat called Etemenanki, "House of the Frontier Between Heaven and Earth," which lay next to the Temple of Marduk.

Nebuchadnezzar II conducted successful military campaigns in Syria and Phoenicia, forcing tribute from Damascus, Tyre and Sidon. He conducted numerous campaigns in Asia Minor, in the "land of the Hatti". Like the Assyrians, the Babylonians had to campaign yearly in order to control their colonies.

In 601 BC, Nebuchadnezzar II was involved in a major, but inconclusive, battle against the Egyptians. In 599 BC, he invaded Arabia and routed the Arabs at Qedar. In 597 BC, he invaded Judah and captured Jerusalem and deposed its king Jehoiachin. Egyptian and Babylonian armies fought each other for control of the near east throughout much of Nebuchadnezzar's reign, and this encouraged king Zedekiah of Judah to revolt. After an 18-month siege, Jerusalem was captured in 587 BC, and thousands of Jews were deported to Babylon, and Solomon's Temple was razed to the ground.

By 572 Nebuchadnezzar was in full control of Babylonia, Assyria, Phoenicia, Israel, Philistinia, northern Arabia, and parts of Asia Minor. Nebuchadnezzar fought the Pharaohs Psammetichus II and Apries throughout his reign, and in 568 BC during the reign of Pharaoh Amasis II, invaded Egypt itself.[6]

Amel-Marduk 562–560 BC

Amel-Marduk was the son and successor of Nebuchadnezzar II. He reigned only two years (562–560 BC). According to the Biblical Book of Kings, he pardoned and released Jehoiachin, king of Judah, who had been a prisoner in Babylon for thirty-seven years. Allegedly, because Amel-Marduk tried to modify his father's policies, he was murdered by Neriglissar, his brother-in-law.

Neriglissar 560–556 BC

Babylonian wall relief in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin

Neriglissar appears to have been a more stable ruler, conducting a number of public works, restoring temples etc.

He conducted successful military campaigns against Cilicia, which had threatened Babylonian interests. Neriglissar however reigned for only four years, being succeeded by the young Labashi-Marduk.

It is unclear if Neriglissar was himself a member of the Chaldean tribe, or a native of the city of Babylon.

Labashi-Marduk 556 BC

Labashi-Marduk was a king of Babylon (556 BC), and son of Neriglissar. Labashi-Marduk succeeded his father when still only a boy, after the latter's four-year reign. He was murdered in a conspiracy only nine months after his inauguration.[citation needed] Nabonidus was consequently chosen as the new king.

Nabonidus 556–539 BC

Nabonidus' (Nabû-na'id in Babylonian) noble credentials are not clear, although he was not a Chaldean but from Assyria, in the city of Harran. He says himself in his inscriptions that he is of unimportant origins.[7] Similarly, his mother, Adda-Guppi,[8] who lived to high age and may have been connected to the temple of the Akkadian moon-god Sîn in Harran; in her inscriptions does not mention her descent. His father was Nabû-balatsu-iqbi, a commoner.[9]

For long periods he entrusted rule to his son, Prince Belshazzar. He was a capable soldier but poor politician. All of this left him somewhat unpopular with many of his subjects, particularly the priesthood and the military class.[10]

The Marduk priesthood hated Nabonidus because of his suppression of Marduk's cult and his elevation of the cult of the moon-god Sin.[11][12] When Cyrus the Great conquered Babylonia, he portrayed himself as the savior chosen by Marduk to restore order and justice.[13]

To the east, the Persians had been growing in strength, and Cyrus the Great was very popular in Babylon itself.[14][15] A sense of Nabonidus' religiously-based negative image survives in Jewish literature, such as the works of Josephus,[16] and the Jews initially greeted the Persians as liberators.[17]

Fall of Babylon

In 549 BC Cyrus the Great, the Achaemenid king of Persia, revolted against his suzerain Astyages, king of Media, at Ecbatana. Astyages' army betrayed him to his enemy, and Cyrus established himself as ruler of all the Iranic peoples, as well as the pre-Iranian Elamites and Gutians.

In 539 BC, Cyrus invaded Babylon. Nabonidus sent his son Belshazzar to head off the huge Persian army; however, already massively outnumbered, Belshazzar was betrayed by Gobryas, governor of Assyria, who switched his forces over to the Persian side. The Babylonian forces were overwhelmed at the battle of Opis. Nabonidus fled to Borsippa, and on 12 October, after Cyrus' engineers had diverted the waters of the Euphrates, "the soldiers of Cyrus entered Babylon without fighting." Belshazzar in Xenophon is reported to have been killed, but his account is not held to be reliable here.[18] Nabonidus surrendered and was deported. Gutian guards were placed at the gates of the great temple of Bel, where the services continued without interruption. Cyrus arrived in Babylon on 3 October, Gobryas having acted for him in his absence. Gobryas was then made governor of the province of Babylon.

Cyrus claimed to be the legitimate successor of the ancient Babylonian kings and the avenger of Bel-Marduk, who was assumed to be wrathful at the impiety of Nabonidus in removing the images of the local gods from their ancestral shrines, to his capital Babylon. Nabonidus, in fact, had excited a strong feeling against himself by attempting to centralize the religion of Babylonia in the temple of Marduk at Babylon, and while he had thus alienated the local priesthoods, the military party despised him on account of his antiquarian tastes. He seems to have left the defense of his kingdom to others, occupying himself with the more congenial work of excavating the foundation records of the temples and determining the dates of their builders.

The invasion of Babylonia by Cyrus was doubtless facilitated by the existence of a disaffected party in the state, as well and the presence of foreign exiles like the Jews. Accordingly, one of Cyrus' first acts was to allow these exiles to return to their homelands, carrying with them the images of their gods and their sacred vessels. The permission to do so was embodied in a proclamation, whereby the conqueror endeavored to justify his claim to the Babylonian throne. The feeling was still strong that none had a right to rule over western Asia until he had been consecrated to the office by Bel and his priests; and accordingly, Cyrus henceforth assumed the imperial title of "King of Babylon."

Babylon, like Assyria, became a colony of Achaemenid Persia.

See also

- List of Kings of Babylon

- Cylinder of Nabonidus

- Timeline of the Assyrian Empire

References

^ John F. A. Sawyer; David J. A. Clines (1 April 1983). Midian, Moab and Edom: The History and Archaeology of Late Bronze and Iron Age Jordan and North-West Arabia. A&C Black. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-567-17445-1..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Talley Ornan, The Triumph of the Symbol: Pictorial Representation of Deities in Mesopotamia and the Biblical Image Ban (Göttingen: Academic Press Fribourg, 2005), 4 n. 6

^ A Companion to Assyria : page 192

^ Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq, 3rd ed., Penguin Books, London, 1991 pp. 373–74

^ Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq, 3rd ed., Penguin Books, London, 1991 p. 375

^ "Nebuchadnezzar." Encyclopedia of World Biography. 2004. Encyclopedia.com.

^ M. Heinz and M.H. Feldman (eds.), Representations of political power: Case histories from times of change and dissolving order in the ancient Near East (Winona Lake IN: Eisenbrauns 2007), 137–66.

^ Joan Oates, Babylon, revised ed., Thames & Hudson, 1986, p. 132

^ Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq, 3rd ed., Penguin Books, London, 1991, p. 381

^ John Haywood, The Penguin Historical Atlas of Ancient Civilizations, Penguin Books Ltd. London, 2005, p. 49

^ A.T. Olmstead, History of the Persian Empire, Univ. of Chicago Press, 1948, p. 38

^ Joan Oates, Babylon, revised ed., Thames & Hudson, 1986, p. 133

^ Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq, 3rd ed., Penguin Books, London, 1991, p. 382

^ Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq, 3rd ed., Penguin Books, London, 1991, pp. 381–82

^ Joan Oates, Babylon, revised ed., Thames & Hudson, 1986, pp. 134–35

^ Josephus, The New Complete Works, translated by William Whiston, Kregel Publications, 1999, "Antiquites" Book 10:11, p. 354

^ Isaiah 45 | Biblegateway.com

^ Harper's Bible Dictionary, ed. by Achtemeier, etc., Harper & Row, San Francisco, 1985, p. 103

Comments

Post a Comment