Properties of water

| |||

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

IUPAC name water, oxidane | |||

| Other names Hydrogen hydroxide (HH or HOH), hydrogen oxide, dihydrogen monoxide (DHMO) (systematic name[1]), hydrogen monoxide, dihydrogen oxide, hydric acid, hydrohydroxic acid, hydroxic acid, hydrol,[2] μ-oxido dihydrogen, κ1-hydroxyl hydrogen(0) | |||

| Identifiers | |||

CAS Number |

| ||

3D model (JSmol) |

| ||

Beilstein Reference | 3587155 | ||

ChEBI |

| ||

ChEMBL |

| ||

ChemSpider |

| ||

Gmelin Reference | 117 | ||

PubChem CID |

| ||

RTECS number | ZC0110000 | ||

UNII |

| ||

InChI

| |||

SMILES

| |||

| Properties | |||

Chemical formula | H 2O | ||

Molar mass | 18.01528(33) g/mol | ||

| Appearance | White crystalline solid, almost colorless liquid with a hint of blue, colorless gas[3] | ||

Odor | None | ||

Density | Liquid:[4] 0.9998396 g/mL at 0 °C 0.9970474 g/mL at 25 °C 0.961893 g/mL at 95 °C Solid:[5] 0.9167 g/ml at 0 °C | ||

Melting point | 0.00 °C (32.00 °F; 273.15 K) [a] | ||

Boiling point | 99.98 °C (211.96 °F; 373.13 K) [6][a] | ||

Solubility in water | N/A | ||

Solubility | Poorly soluble in haloalkanes, aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons, ethers.[7] Improved solubility in carboxylates, alcohols, ketones, amines. Miscible with methanol, ethanol, propanol, isopropanol, acetone, glycerol, 1,4-dioxane, tetrahydrofuran, sulfolane, acetaldehyde, dimethylformamide, dimethoxyethane, dimethyl sulfoxide, acetonitrile. Partially miscible with Diethyl ether, Methyl Ethyl Ketone, Dichloromethane, Ethyl Acetate, Bromine. | ||

Vapor pressure | 3.1690 kilopascals or 0.031276 atm[8] | ||

Acidity (pKa) | 13.995[9][10][b] | ||

Basicity (pKb) | 13.995 | ||

Conjugate acid | Hydronium | ||

Conjugate base | Hydroxide | ||

Thermal conductivity | 0.6065 W/(m·K)[13] | ||

Refractive index (nD) | 1.3330 (20 °C)[14] | ||

Viscosity | 0.890 cP[15] | ||

| Structure | |||

Crystal structure | Hexagonal | ||

Point group | C2v | ||

Molecular shape | Bent | ||

Dipole moment | 1.8546 D[16] | ||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Heat capacity (C) | 75.385 ± 0.05 J/(mol·K)[17] | ||

Std molar entropy (S | 69.95 ± 0.03 J/(mol·K)[17] | ||

Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH | −285.83 ± 0.04 kJ/mol[7][17] | ||

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG˚) | −237.24 kJ/mol[7] | ||

| Hazards | |||

| Main hazards | Drowning Avalanche (as snow)

| ||

NFPA 704 |  0 0 0 | ||

Flash point | Non-flammable | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Other cations | Hydrogen sulfide Hydrogen selenide Hydrogen telluride Hydrogen polonide Hydrogen peroxide | ||

Related solvents | Acetone Methanol | ||

Supplementary data page | |||

Structure and properties | Refractive index (n), Dielectric constant (εr), etc. | ||

Thermodynamic data | Phase behaviour solid–liquid–gas | ||

Spectral data | UV, IR, NMR, MS | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

Infobox references | |||

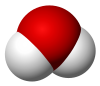

Water (H

2O) is a polar inorganic compound that is at room temperature a tasteless and odorless liquid, which is nearly colorless apart from an inherent hint of blue. It is by far the most studied chemical compound and is described as the "universal solvent" [18][19] and the "solvent of life".[20] It is the most abundant substance on Earth[21] and the only common substance to exist as a solid, liquid, and gas on Earth's surface.[22] It is also the third most abundant molecule in the universe.[21]

Water molecules form hydrogen bonds with each other and are strongly polar. This polarity allows it to dissociate ions in salts and bond to other polar substances such as alcohols and acids, thus dissolving them. Its hydrogen bonding causes its many unique properties, such as having a solid form less dense than its liquid form,[c] a relatively high boiling point of 100 °C for its molar mass, and a high heat capacity.

Water is amphoteric, meaning that it can exhibit properties of an acid or a base, depending on the pH of the solution that it is in; it readily produces both H+

and OH−

ions.[c] Related to its amphoteric character, it undergoes self-ionization. The product of the activities, or approximately, the concentrations of H+

and OH−

is a constant, so their respective concentrations are inversely proportional to each other.[23]

Contents

1 Physical properties

1.1 Water, ice, and vapor

1.1.1 Heat capacity and heats of vaporization and fusion

1.1.2 Density of water and ice

1.1.3 Density of saltwater and ice

1.1.4 Miscibility and condensation

1.1.5 Vapor pressure

1.1.6 Compressibility

1.1.7 Triple point

1.1.8 Melting point

1.2 Electrical properties

1.2.1 Electrical conductivity

1.3 Polarity and hydrogen bonding

1.3.1 Cohesion and adhesion

1.3.2 Surface tension

1.3.3 Capillary action

1.3.4 Water as a solvent

1.3.5 Quantum tunneling

1.4 Electromagnetic absorption

2 Structure

3 Chemical properties

3.1 Geochemistry

3.2 Acidity in nature

4 Isotopologues

5 Occurrence

6 Reactions

6.1 Acid-base reactions

6.2 Ligand chemistry

6.3 Organic chemistry

6.4 Water in redox reactions

6.5 Electrolysis

7 History

8 Nomenclature

9 See also

10 Footnotes

11 References

11.1 Notes

11.2 Bibliography

12 Further reading

13 External links

Physical properties

Water is the chemical substance with chemical formula H

2O; one molecule of water has two hydrogen atoms covalently bonded to a single oxygen atom.[24]

Water is a tasteless, odorless liquid at ambient temperature and pressure. Liquid water has weak absorption bands at wavelengths of around 750 nm which cause it to appear to have a blue colour.[3] This can easily be observed in a water-filled bath or wash-basin whose lining is white. Large ice crystals, as in glaciers, also appear blue.

Unlike other analogous hydrides of the oxygen family, water is primarily a liquid under standard conditions due to hydrogen bonding. The molecules of water are constantly moving in relation to each other, and the hydrogen bonds are continually breaking and reforming at timescales faster than 200 femtoseconds (2×10−13 seconds).[25]

However, these bonds are strong enough to create many of the peculiar properties of water, some of which make it integral to life.

Water, ice, and vapor

Within the Earth's atmosphere and surface, the liquid phase is the most common and is the form that is generally denoted by the word "water". The solid phase of water is known as ice and commonly takes the structure of hard, amalgamated crystals, such as ice cubes, or loosely accumulated granular crystals, like snow. Aside from common hexagonal crystalline ice, other crystalline and amorphous phases of ice are known. The gaseous phase of water is known as water vapor (or steam). Visible steam and clouds are formed from minute droplets of water suspended in the air.

Water also forms a supercritical fluid. The critical temperature is 647 K and the critical pressure is 22.064 MPa. In nature this only rarely occurs in extremely hostile conditions. A likely example of naturally occurring supercritical water is in the hottest parts of deep water hydrothermal vents, in which water is heated to the critical temperature by volcanic plumes and the critical pressure is caused by the weight of the ocean at the extreme depths where the vents are located. This pressure is reached at a depth of about 2200 meters: much less than the mean depth of the ocean (3800 meters).[26]

Heat capacity and heats of vaporization and fusion

Heat of vaporization of water from melting to critical temperature

Water has a very high specific heat capacity of 4.1814 J/(g·K) at 25 °C – the second highest among all the heteroatomic species (after ammonia), as well as a high heat of vaporization (40.65 kJ/mol or 2257 kJ/kg at the normal boiling point), both of which are a result of the extensive hydrogen bonding between its molecules. These two unusual properties allow water to moderate Earth's climate by buffering large fluctuations in temperature. Most of the additional energy stored in the climate system since 1970 has accumulated in the oceans.[27]

The specific enthalpy of fusion (more commonly known as latent heat) of water is 333.55 kJ/kg at 0 °C: the same amount of energy is required to melt ice as to warm ice from −160 °C up to its melting point or to heat the same amount of water by about 80 °C. Of common substances, only that of ammonia is higher. This property confers resistance to melting on the ice of glaciers and drift ice. Before and since the advent of mechanical refrigeration, ice was and still is in common use for retarding food spoilage.

The specific heat capacity of ice at −10 °C is 2.03 J/(g·K)[28]

and the heat capacity of steam at 100 °C is 2.08 J/(g·K).[29]

Density of water and ice

Density of ice and water as a function of temperature

The density of water is about 1 gram per cubic centimetre (62 lb/cu ft): this relationship was originally used to define the gram.[30] The density varies with temperature, but not linearly: as the temperature increases, the density rises to a peak at 3.98 °C (39.16 °F) and then decreases.[31] This unusual negative thermal expansion below 4 °C (39 °F) is also observed in molten silica.[32] Regular, hexagonal ice is also less dense than liquid water—upon freezing, the density of water decreases by about 9%.[33] Other substances that expand on freezing are silicon (melting point of 1,687 K (1,414 °C; 2,577 °F)), gallium (melting point of 303 K (30 °C; 86 °F)|, germanium (melting point of 1,211 K (938 °C; 1,720 °F)), antimony (melting point of 904 K (631 °C; 1,168 °F)), and bismuth (melting point of 545 K (272 °C; 521 °F)). Also, fairly pure silicon has a negative coefficient of thermal expansion for temperatures between about 18 and 120 kelvins.[34]

These effects are due to the reduction of thermal motion with cooling, which allows water molecules to form more hydrogen bonds that prevent the molecules from coming close to each other.[31] While below 4 °C the breakage of hydrogen bonds due to freezing allows water molecules to pack closer despite the increase in the thermal motion (which tends to expand a liquid), above 4 °C water expands as the temperature increases.[31] Water near the boiling point is about 4% less dense than water at 4 °C (39 °F).[33][d]

Under increasing pressure, ice undergoes a number of transitions to other polymorphs with higher density than liquid water, such as ice II, ice III, high-density amorphous ice (HDA), and very-high-density amorphous ice (VHDA).[35][36]

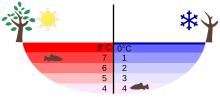

Temperature distribution in a lake in summer and winter

The unusual density curve and lower density of ice than of water is vital to life—if water were most dense at the freezing point, then in winter the very cold water at the surface of lakes and other water bodies would sink, the lake could freeze from the bottom up, and all life in them would be killed.[33] Furthermore, given that water is a good thermal insulator (due to its heat capacity), some frozen lakes might not completely thaw in summer.[33] The layer of ice that floats on top insulates the water below.[37] Water at about 4 °C (39 °F) also sinks to the bottom, thus keeping the temperature of the water at the bottom constant (see diagram).[33]

Density of saltwater and ice

WOA surface density

The density of salt water depends on the dissolved salt content as well as the temperature. Ice still floats in the oceans, otherwise they would freeze from the bottom up. However, the salt content of oceans lowers the freezing point by about 1.9 °C[38] (see here for explanation) and lowers the temperature of the density maximum of water to the former freezing point at 0 °C. This is why, in ocean water, the downward convection of colder water is not blocked by an expansion of water as it becomes colder near the freezing point. The oceans' cold water near the freezing point continues to sink. So creatures that live at the bottom of cold oceans like the Arctic Ocean generally live in water 4 °C colder than at the bottom of frozen-over fresh water lakes and rivers.

As the surface of salt water begins to freeze (at −1.9 °C[38] for normal salinity seawater, 3.5%) the ice that forms is essentially salt-free, with about the same density as freshwater ice. This ice floats on the surface, and the salt that is "frozen out" adds to the salinity and density of the sea water just below it, in a process known as brine rejection. This denser salt water sinks by convection and the replacing seawater is subject to the same process. This produces essentially freshwater ice at −1.9 °C[38] on the surface. The increased density of the sea water beneath the forming ice causes it to sink towards the bottom. On a large scale, the process of brine rejection and sinking cold salty water results in ocean currents forming to transport such water away from the Poles, leading to a global system of currents called the thermohaline circulation.

Miscibility and condensation

Red line shows saturation

Water is miscible with many liquids, including ethanol in all proportions. Water and most oils are immiscible usually forming layers according to increasing density from the top. This can be predicted by comparing the polarity. Water being a relatively polar compound will tend to be miscible with liquids of high polarity such as ethanol and acetone, whereas compounds with low polarity will tend to be immiscible and poorly soluble such as with hydrocarbons.

As a gas, water vapor is completely miscible with air. On the other hand, the maximum water vapor pressure that is thermodynamically stable with the liquid (or solid) at a given temperature is relatively low compared with total atmospheric pressure.

For example, if the vapor's partial pressure is 2% of atmospheric pressure and the air is cooled from 25 °C, starting at about 22 °C water will start to condense, defining the dew point, and creating fog or dew. The reverse process accounts for the fog burning off in the morning. If the humidity is increased at room temperature, for example, by running a hot shower or a bath, and the temperature stays about the same, the vapor soon reaches the pressure for phase change, and then condenses out as minute water droplets, commonly referred to as steam.

A saturated gas or one with 100% relative humidity is when the vapor pressure of water in the air is at equilibrium with vapor pressure due to (liquid) water; water (or ice, if cool enough) will fail to lose mass through evaporation when exposed to saturated air. Because the amount of water vapor in air is small, relative humidity, the ratio of the partial pressure due to the water vapor to the saturated partial vapor pressure, is much more useful.

Vapor pressure above 100% relative humidity is called super-saturated and can occur if air is rapidly cooled, for example, by rising suddenly in an updraft.[e]

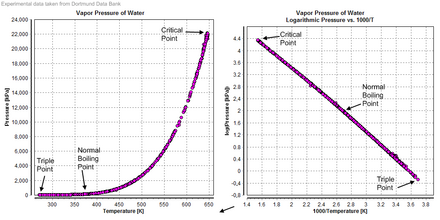

Vapor pressure

Vapor pressure diagrams of water

Compressibility

The compressibility of water is a function of pressure and temperature. At 0 °C, at the limit of zero pressure, the compressibility is 6990510000000000000♠5.1×10−10 Pa−1. At the zero-pressure limit, the compressibility reaches a minimum of 6990440000000000000♠4.4×10−10 Pa−1 around 45 °C before increasing again with increasing temperature. As the pressure is increased, the compressibility decreases, being 6990390000000000000♠3.9×10−10 Pa−1 at 0 °C and 100 megapascals (1,000 bar).[39]

The bulk modulus of water is about 2.2 GPa.[40] The low compressibility of non-gases, and of water in particular, leads to their often being assumed as incompressible. The low compressibility of water means that even in the deep oceans at 4 km depth, where pressures are 40 MPa, there is only a 1.8% decrease in volume.[40]

Triple point

The Solid/Liquid/Vapour triple point of liquid water, ice Ih and water vapor in the lower left portion of a water phase diagram.

The temperature and pressure at which ordinary solid, liquid, and gaseous water coexist in equilibrium is a triple point of water. Since 1954, this point had been used to define the base unit of temperature, the kelvin[41][42] but, starting in 2019, the kelvin will be defined using the Boltzmann constant, rather than the triple point of water.[43]

Due to the existence of many polymorphs (forms) of ice, water has other triple points, which have either three polymorphs of ice or two polymorphs of ice and liquid in equilibrium.[42]Gustav Heinrich Johann Apollon Tammann in Göttingen produced data on several other triple points in the early 20th century. Kamb and others documented further triple points in the 1960s.[44][45][46]

| Phases in stable equilibrium | Pressure | Temperature |

|---|---|---|

| liquid water, ice Ih, and water vapor | 611.657 Pa[47] | 273.16 K (0.01 °C) |

| liquid water, ice Ih, and ice III | 209.9 MPa | 251 K (−22 °C) |

| liquid water, ice III, and ice V | 350.1 MPa | −17.0 °C |

| liquid water, ice V, and ice VI | 632.4 MPa | 0.16 °C |

| ice Ih, Ice II, and ice III | 213 MPa | −35 °C |

| ice II, ice III, and ice V | 344 MPa | −24 °C |

| ice II, ice V, and ice VI | 626 MPa | −70 °C |

Melting point

The melting point of ice is 0 °C (32 °F; 273 K) at standard pressure; however, pure liquid water can be supercooled well below that temperature without freezing if the liquid is not mechanically disturbed. It can remain in a fluid state down to its homogeneous nucleation point of about 231 K (−42 °C; −44 °F).[48] The melting point of ordinary hexagonal ice falls slightly under moderately high pressures, by 0.0073 °C (0.0131 °F)/atm[f] or about 0.5 °C (0.90 °F)/70 atm[g][49] as the stabilization energy of hydrogen bonding is exceeded by intermolecular repulsion, but as ice transforms into its allotropes (see crystalline states of ice) above 209.9 MPa (2,072 atm), the melting point increases markedly with pressure, i.e., reaching 355 K (82 °C) at 2.216 GPa (21,870 atm) (triple point of Ice VII[50]).

Electrical properties

Electrical conductivity

Pure water containing no exogenous ions is an excellent insulator, but not even "deionized" water is completely free of ions. Water undergoes auto-ionization in the liquid state, when two water molecules form one hydroxide anion (OH−

) and one hydronium cation (H

3O+

).

Because water is such a good solvent, it almost always has some solute dissolved in it, often a salt. If water has even a tiny amount of such an impurity, then the ions can carry charges back and forth, allowing the water to conduct electricity far more readily.

It is known that the theoretical maximum electrical resistivity for water is approximately 18.2 MΩ·cm (182 kΩ·m) at 25 °C.[51] This figure agrees well with what is typically seen on reverse osmosis, ultra-filtered and deionized ultra-pure water systems used, for instance, in semiconductor manufacturing plants. A salt or acid contaminant level exceeding even 100 parts per trillion (ppt) in otherwise ultra-pure water begins to noticeably lower its resistivity by up to several kΩ·m.[citation needed]

In pure water, sensitive equipment can detect a very slight electrical conductivity of 0.05501 ± 0.0001 µS/cm at 25.00 °C.[51] Water can also be electrolyzed into oxygen and hydrogen gases but in the absence of dissolved ions this is a very slow process, as very little current is conducted. In ice, the primary charge carriers are protons (see proton conductor).[52] Ice was previously thought to have a small but measurable conductivity of 1×10−10 S/cm, but this conductivity is now thought to be almost entirely from surface defects, and without those, ice is an insulator with an immeasurably small conductivity.[31]

Polarity and hydrogen bonding

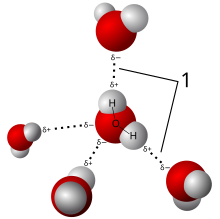

A diagram showing the partial charges on the atoms in a water molecule

An important feature of water is its polar nature. The structure has a bent molecular geometry for the two hydrogens from the oxygen vertex. The oxygen atom also has two lone pairs of electrons. One effect usually ascribed to the lone pairs is that the H–O–H gas phase bend angle is 104.48°,[53] which is smaller than the typical tetrahedral angle of 109.47°. The lone pairs are closer to the oxygen atom than the electrons sigma bonded to the hydrogens, so they require more space. The increased repulsion of the lone pairs forces the O–H bonds closer to each other.[54]

Another consequence of its structure is that water is a polar molecule. Due to the difference in electronegativity, a bond dipole moment points from each H to the O, making the oxygen partially negative and each hydrogen partially positive. A large molecular dipole, points from a region between the two hydrogen atoms to the oxygen atom. The charge differences cause water molecules to aggregate (the relatively positive areas being attracted to the relatively negative areas). This attraction, hydrogen bonding, explains many of the properties of water, such as its solvent properties.[55]

Although hydrogen bonding is a relatively weak attraction compared to the covalent bonds within the water molecule itself, it is responsible for a number of water's physical properties. These properties include its relatively high melting and boiling point temperatures: more energy is required to break the hydrogen bonds between water molecules. In contrast, hydrogen sulfide (H

2S), has much weaker hydrogen bonding due to sulfur's lower electronegativity. H

2S is a gas at room temperature, in spite of hydrogen sulfide having nearly twice the molar mass of water. The extra bonding between water molecules also gives liquid water a large specific heat capacity. This high heat capacity makes water a good heat storage medium (coolant) and heat shield.

Cohesion and adhesion

Dew drops adhering to a spider web

Water molecules stay close to each other (cohesion), due to the collective action of hydrogen bonds between water molecules. These hydrogen bonds are constantly breaking, with new bonds being formed with different water molecules; but at any given time in a sample of liquid water, a large portion of the molecules are held together by such bonds.[56]

Water also has high adhesion properties because of its polar nature. On extremely clean/smooth glass the water may form a thin film because the molecular forces between glass and water molecules (adhesive forces) are stronger than the cohesive forces.

In biological cells and organelles, water is in contact with membrane and protein surfaces that are hydrophilic; that is, surfaces that have a strong attraction to water. Irving Langmuir observed a strong repulsive force between hydrophilic surfaces. To dehydrate hydrophilic surfaces—to remove the strongly held layers of water of hydration—requires doing substantial work against these forces, called hydration forces. These forces are very large but decrease rapidly over a nanometer or less.[57] They are important in biology, particularly when cells are dehydrated by exposure to dry atmospheres or to extracellular freezing.[58]

Surface tension

This paper clip is under the water level, which has risen gently and smoothly. Surface tension prevents the clip from submerging and the water from overflowing the glass edges.

Temperature dependence of the surface tension of pure water

Water has an unusually high surface tension of 71.99 mN/m at 25 °C[59] which is caused by the strength of the hydrogen bonding between water molecules.[60] This allows insects to walk on water.[60]

Capillary action

Because water has strong cohesive and adhesive forces, it exhibits capillary action.[61] Strong cohesion from hydrogen bonding and adhesion allows trees to transport water more than 100 m upward.[60]

Water as a solvent

Presence of colloidal calcium carbonate from high concentrations of dissolved lime turns the water of Havasu Falls turquoise.

Water is an excellent solvent due to its high dielectric constant.[62] Substances that mix well and dissolve in water are known as hydrophilic ("water-loving") substances, while those that do not mix well with water are known as hydrophobic ("water-fearing") substances.[63] The ability of a substance to dissolve in water is determined by whether or not the substance can match or better the strong attractive forces that water molecules generate between other water molecules. If a substance has properties that do not allow it to overcome these strong intermolecular forces, the molecules are precipitated out from the water. Contrary to the common misconception, water and hydrophobic substances do not "repel", and the hydration of a hydrophobic surface is energetically, but not entropically, favorable.

When an ionic or polar compound enters water, it is surrounded by water molecules (hydration). The relatively small size of water molecules (~ 3 angstroms) allows many water molecules to surround one molecule of solute. The partially negative dipole ends of the water are attracted to positively charged components of the solute, and vice versa for the positive dipole ends.

In general, ionic and polar substances such as acids, alcohols, and salts are relatively soluble in water, and non-polar substances such as fats and oils are not. Non-polar molecules stay together in water because it is energetically more favorable for the water molecules to hydrogen bond to each other than to engage in van der Waals interactions with non-polar molecules.

An example of an ionic solute is table salt; the sodium chloride, NaCl, separates into Na+

cations and Cl−

anions, each being surrounded by water molecules. The ions are then easily transported away from their crystalline lattice into solution. An example of a nonionic solute is table sugar. The water dipoles make hydrogen bonds with the polar regions of the sugar molecule (OH groups) and allow it to be carried away into solution.

Quantum tunneling

The quantum tunneling dynamics in water was reported as early as 1992. At that time it was known that there are motions which destroy and regenerate the weak hydrogen bond by internal rotations of the substituent water monomers.[64] On 18 March 2016, it was reported that the hydrogen bond can be broken by quantum tunneling in the water hexamer. Unlike previously reported tunneling motions in water, this involved the concerted breaking of two hydrogen bonds.[65] Later in the same year, the discovery of the quantum tunneling of water molecules was reported.[66]

Electromagnetic absorption

Water is relatively transparent to visible light, near ultraviolet light, and far-red light, but it absorbs most ultraviolet light, infrared light, and microwaves. Most photoreceptors and photosynthetic pigments utilize the portion of the light spectrum that is transmitted well through water. Microwave ovens take advantage of water's opacity to microwave radiation to heat the water inside of foods. Water's light blue colour is caused by weak absorption in the red part of the visible spectrum.[3][67]

Structure

Model of hydrogen bonds (1) between molecules of water

A single water molecule can participate in a maximum of four hydrogen bonds because it can accept two bonds using the lone pairs on oxygen and donate two hydrogen atoms. Other molecules like hydrogen fluoride, ammonia and methanol can also form hydrogen bonds. However, they do not show anomalous thermodynamic, kinetic or structural properties like those observed in water because none of them can form four hydrogen bonds: either they cannot donate or accept hydrogen atoms, or there are steric effects in bulky residues. In water, intermolecular tetrahedral structures form due to the four hydrogen bonds, thereby forming an open structure and a three-dimensional bonding network, resulting in the anomalous decrease in density when cooled below 4 °C. This repeated, constantly reorganizing unit defines a three-dimensional network extending throughout the liquid. This view is based upon neutron scattering studies and computer simulations, and it makes sense in the light of the unambiguously tetrahedral arrangement of water molecules in ice structures.

However, there is an alternative theory for the structure of water. In 2004, a controversial paper from Stockholm University suggested that water molecules in liquid form typically bind not to four but to only two others; thus forming chains and rings. The term "string theory of water" (which is not to be confused with the string theory of physics) was coined. These observations were based upon X-ray absorption spectroscopy that probed the local environment of individual oxygen atoms.[68]

Chemical properties

At standard conditions, water is a polar liquid that slightly dissociates disproportionately into a hydronium ion and hydroxide ion.

- 2 H

2O ⇌ H

3O+

+ OH−

The ionic product of pure water,Kw has a value of about 10−14 at 25 °C; see data page for values at other temperatures. Pure water has a concentration of the hydroxide ion (OH−

) equal to that of the hydrogen ion (H+

), which gives a pH of 7 at 25 °C.[69]

Geochemistry

Action of water on rock over long periods of time typically leads to weathering and water erosion, physical processes that convert solid rocks and minerals into soil and sediment, but under some conditions chemical reactions with water occur as well, resulting in metasomatism or mineral hydration, a type of chemical alteration of a rock which produces clay minerals. It also occurs when Portland cement hardens.

Water ice can form clathrate compounds, known as clathrate hydrates, with a variety of small molecules that can be embedded in its spacious crystal lattice. The most notable of these is methane clathrate, 4 CH

4·23H

2O, naturally found in large quantities on the ocean floor.

Acidity in nature

Rain is generally mildly acidic, with a pH between 5.2 and 5.8 if not having any acid stronger than carbon dioxide.[70] If high amounts of nitrogen and sulfur oxides are present in the air, they too will dissolve into the cloud and rain drops, producing acid rain.

Isotopologues

Several isotopes of both hydrogen and oxygen exist, giving rise to several known isotopologues of water. Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water is the current international standard for water isotopes. Naturally occurring water is almost completely composed of the neutron-less hydrogen isotope protium. Only 155 ppm include deuterium (2

H or D), a hydrogen isotope with one neutron, and fewer than 20 parts per quintillion include tritium (3

H or T), which has two neutrons. Oxygen also has three stable isotopes, with 16

O present in 99.76%, 17

O in 0.04%, and 18

O in 0.2% of water molecules.[71]

Deuterium oxide, D

2O, is also known as heavy water because of its higher density. It is used in nuclear reactors as a neutron moderator. Tritium is radioactive, decaying with a half-life of 4500 days; THO exists in nature only in minute quantities, being produced primarily via cosmic ray-induced nuclear reactions in the atmosphere. Water with one protium and one deuterium atom HDO occurs naturally in ordinary water in low concentrations (~0.03%) and D

2O in far lower amounts (0.000003%) and any such molecules are temporary as the atoms recombine.

The most notable physical differences between H

2O and D

2O, other than the simple difference in specific mass, involve properties that are affected by hydrogen bonding, such as freezing and boiling, and other kinetic effects. This is because the nucleus of deuterium is twice as heavy as protium, and this causes noticeable differences in bonding energies. The difference in boiling points allows the isotopologues to be separated. The self-diffusion coefficient of H

2O at 25 °C is 23% higher than the value of D

2O.[72] Because water molecules exchange hydrogen atoms with one another, hydrogen deuterium oxide (DOH) is much more common in low-purity heavy water than pure dideuterium monoxide D

2O.

Consumption of pure isolated D

2O may affect biochemical processes – ingestion of large amounts impairs kidney and central nervous system function. Small quantities can be consumed without any ill-effects; humans are generally unaware of taste differences,[73] but sometimes report a burning sensation[74] or sweet flavor.[75] Very large amounts of heavy water must be consumed for any toxicity to become apparent. Rats, however, are able to avoid heavy water by smell, and it is toxic to many animals.[76]

Light water refers to deuterium-depleted water (DDW), water in which the deuterium content has been reduced below the standard 155 ppm level.

Occurrence

It is the most abundant substance on Earth and also the third most abundant molecule in the universe, after H

2 and CO.[21] 0.23 ppm of the earth's mass is water and 97.39% of the global water volume of 1.38×109 km3 is found in the oceans.[77]

Reactions

Acid-base reactions

Water is amphoteric: it has the ability to act as either an acid or a base in chemical reactions.[78] According to the Brønsted-Lowry definition, an acid is a proton (H+

) donor and a base is a proton acceptor.[79] When reacting with a stronger acid, water acts as a base; when reacting with a stronger base, it acts as an acid.[79] For instance, water receives an H+

ion from HCl when hydrochloric acid is formed:

HCl

(acid) + H

2O

(base) ⇌ H

3O+

+ Cl−

In the reaction with ammonia, NH

3, water donates a H+

ion, and is thus acting as an acid:

NH

3

(base) + H

2O

(acid) ⇌ NH+

4 + OH−

Because the oxygen atom in water has two lone pairs, water often acts as a Lewis base, or electron pair donor, in reactions with Lewis acids, although it can also react with Lewis bases, forming hydrogen bonds between the electron pair donors and the hydrogen atoms of water. HSAB theory describes water as both a weak hard acid and a weak hard base, meaning that it reacts preferentially with other hard species:

H+

(Lewis acid) + H

2O

(Lewis base) → H

3O+

Fe3+

(Lewis acid) + H

2O

(Lewis base) → Fe(H

2O)3+

6

Cl−

(Lewis base) + H

2O

(Lewis acid) → Cl(H

2O)−

6

When a salt of a weak acid or of a weak base is dissolved in water, water can partially hydrolyze the salt, producing the corresponding base or acid, which gives aqueous solutions of soap and baking soda their basic pH:

Na

2CO

3 + H

2O ⇌ NaOH + NaHCO

3

Ligand chemistry

Water's Lewis base character makes it a common ligand in transition metal complexes, examples of which include metal aquo complexes such as Fe(H

2O)2+

6 to perrhenic acid, which contains two water molecules coordinated to a rhenium center. In solid hydrates, water can be either a ligand or simply lodged in the framework, or both. Thus, FeSO

4·7H

2O consists of [Fe2(H2O)6]2+ centers and one "lattice water". Water is typically a monodentate ligand, i.e., it forms only one bond with the central atom.[80]

Some hydrogen-bonding contacts in FeSO4.7H2O. This metal aquo complex crystallizes with one molecule of "lattice" water, which interacts with the sulfate and with the [Fe(H2O)6]2+ centers.

Organic chemistry

As a hard base, water reacts readily with organic carbocations; for example in a hydration reaction, a hydroxyl group (OH−

) and an acidic proton are added to the two carbon atoms bonded together in the carbon-carbon double bond, resulting in an alcohol. When addition of water to an organic molecule cleaves the molecule in two, hydrolysis is said to occur. Notable examples of hydrolysis are the saponification of fats and the digestion of proteins and polysaccharides. Water can also be a leaving group in SN2 substitution and E2 elimination reactions; the latter is then known as a dehydration reaction.

Water in redox reactions

Water contains hydrogen in the oxidation state +1 and oxygen in the oxidation state −2.[81] It oxidizes chemicals such as hydrides, alkali metals, and some alkaline earth metals.[82][83] One example of an alkali metal reacting with water is:[84]

- 2 Na + 2 H

2O → H

2 + 2 Na+

+ 2 OH−

Some other reactive metals, such as aluminum and beryllium, are oxidized by water as well, but their oxides adhere to the metal and form a passive protective layer.[85] Note that the rusting of iron is a reaction between iron and oxygen[86] that is dissolved in water, not between iron and water.

Water can be oxidized to emit oxygen gas, but very few oxidants react with water even if their reduction potential is greater than the potential of O

2/H

2O. Almost all such reactions require a catalyst.[87]

An example of the oxidation of water is:

- 4 AgF

2 + 2 H

2O → 4 AgF + 4 HF + O

2

Electrolysis

Water can be split into its constituent elements, hydrogen and oxygen, by passing an electric current through it.[88] This process is called electrolysis.

The cathode half reaction is:

- 2 H+

+ 2

e−

→ H

2

The anode half reaction is:

- 2 H

2O → O

2 + 4 H+

+ 4

e−

The gases produced bubble to the surface, where they can be collected or ignited with a flame above the water if this was the intention. The required potential for the electrolysis of pure water is 1.23 V at 25 °C.[88] The operating potential is actually 1.48 V or higher in practical electrolysis.

History

Henry Cavendish showed that water was composed of oxygen and hydrogen in 1781.[89] The first decomposition of water into hydrogen and oxygen, by electrolysis, was done in 1800 by English chemist William Nicholson and Anthony Carlisle.[89][90] In 1805, Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac and Alexander von Humboldt showed that water is composed of two parts hydrogen and one part oxygen.[91]

Gilbert Newton Lewis isolated the first sample of pure heavy water in 1933.[92]

The properties of water have historically been used to define various temperature scales. Notably, the Kelvin, Celsius, Rankine, and Fahrenheit scales were, or currently are, defined by the freezing and boiling points of water. The less common scales of Delisle, Newton, Réaumur and Rømer were defined similarly. The triple point of water is a more commonly used standard point today.

Nomenclature

The accepted IUPAC name of water is oxidane or simply water,[93] or its equivalent in different languages, although there are other systematic names which can be used to describe the molecule. Oxidane is only intended to be used as the name of the mononuclear parent hydride used for naming derivatives of water by substituent nomenclature.[94] These derivatives commonly have other recommended names. For example, the name hydroxyl is recommended over oxidanyl for the –OH group. The name oxane is explicitly mentioned by the IUPAC as being unsuitable for this purpose, since it is already the name of a cyclic ether also known as tetrahydropyran.[95][96]

The simplest systematic name of water is hydrogen oxide. This is analogous to related compounds such as hydrogen peroxide, hydrogen sulfide, and deuterium oxide (heavy water). Using chemical nomenclature for type I ionic binary compounds, water would take the name hydrogen monoxide ,[97] but this is not among the names published by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC).[93] Another name is dihydrogen monoxide, which is a rarely used name of water, and mostly used in the dihydrogen monoxide hoax.

Other systematic names for water include hydroxic acid, hydroxylic acid, and hydrogen hydroxide, using acid and base names.[h] None of these exotic names are used widely. The polarized form of the water molecule, H+

OH−

, is also called hydron hydroxide by IUPAC nomenclature.[98]

Water substance is a term used for hydrogen oxide (H2O) when one does not wish to specify whether one is speaking of liquid water, steam, some form of ice, or a component in a mixture or mineral.

See also

- Chemical bonding of H2O

- Water (data page)

- Dihydrogen monoxide hoax

- Double distilled water

- Electromagnetic absorption by water

- Water model

- Fluid dynamics

- Optical properties of water and ice

- Superheated water

- Hydrogen polyoxide

- Viscosity of water

- Water cluster

- Water dimer

- Water thread experiment

Footnotes

^ ab Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW), used for calibration, melts at 273.1500089(10) K (0.000089(10) °C, and boils at 373.1339 K (99.9839 °C). Other isotopic compositions melt or boil at slightly different temperatures.

^

A commonly quoted value of 15.7 used mainly in organic chemistry for the pKa of water is incorrect.[11][12]

^ ab H+ represents H

3O+

(H

2O)

n and more complex ions that form.

^ (1-0.95865/1.00000) × 100% = 4.135%

^ Adiabatic cooling resulting from the ideal gas law

^ The source gives it as 0.0072°C/atm. However the author defines an atmosphere as 1,000,000 dynes/cm2 (a bar). Using the standard definition of atmosphere, 1,013,250 dynes/cm2, it works out to 0.0073°C/atm

^

Using the fact that 0.5/0.0073 = 68.5

^ Both acid and base names exist for water because it is amphoteric (able to react both as an acid or an alkali)

References

Notes

^ "naming molecular compounds". www.iun.edu. Retrieved 1 October 2018.Sometimes these compounds have generic or common names (e.g., H2O is "water") and they also have systematic names (e.g., H2O, dihydrogen monoxide).

.mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "Definition of Hydrol". Merriam-Webster. (Subscription required (help)).

^ abc Braun, Charles L.; Smirnov, Sergei N. (1993-08-01). "Why is water blue?" (PDF). Journal of Chemical Education. 70 (8): 612. Bibcode:1993JChEd..70..612B. doi:10.1021/ed070p612. ISSN 0021-9584.

^ Riddick 1970, Table of Physical Properties, Water 0b. pg 67-8.

^ Lide 2003, Properties of Ice and Supercooled Water in Section 6.

^ Water in Linstrom, Peter J.; Mallard, William G. (eds.); NIST Chemistry WebBook, NIST Standard Reference Database Number 69, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg (MD), http://webbook.nist.gov (retrieved 2016-5-27)

^ abc Anatolievich, Kiper Ruslan. "Properties of substance: water".

^ Lide 2003, Vapor Pressure of Water From 0 to 370° C in Sec. 6.

^ Lide 2003, Chapter 8: Dissociation Constants of Inorganic Acids and Bases.

^ Weingärtner et al. 2016, p. 13.

^ "What is the pKa of Water". University of California, Davis. 2015-08-09.

^ Silverstein, Todd P.; Heller, Stephen T. (17 April 2017). "pKa Values in the Undergraduate Curriculum: What Is the Real pKa of Water?". Journal of Chemical Education. 94 (6): 690–695. Bibcode:2017JChEd..94..690S. doi:10.1021/acs.jchemed.6b00623.

^ Ramires, Maria L. V.; Castro, Carlos A. Nieto de; Nagasaka, Yuchi; Nagashima, Akira; Assael, Marc J.; Wakeham, William A. (1995-05-01). "Standard Reference Data for the Thermal Conductivity of Water". Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. 24 (3): 1377–1381. Bibcode:1995JPCRD..24.1377R. doi:10.1063/1.555963. ISSN 0047-2689.

^ Lide 2003, 8—Concentrative Properties of Aqueous Solutions: Density, Refractive Index, Freezing Point Depression, and Viscosity.

^ Lide 2003, 6.186.

^ Lide 2003, 9—Dipole Moments.

^ abc Water in Linstrom, Peter J.; Mallard, William G. (eds.); NIST Chemistry WebBook, NIST Standard Reference Database Number 69, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg (MD), http://webbook.nist.gov (retrieved 2014-06-01)

^ Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997, p. 620.

^ "Water, the Universal Solvent". USGS.

^ Reece et al. 2013, p. 48.

^ abc Weingärtner et al. 2016, p. 2.

^ Reece et al. 2013, p. 44.

^ "Autoprotolysis constant". IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology. IUPAC. 2009. doi:10.1351/goldbook.A00532. ISBN 978-0-9678550-9-7.

^ Campbell, Williamson & Heyden 2006.

^

Smith, Jared D.; Christopher D. Cappa; Kevin R. Wilson; Ronald C. Cohen; Phillip L. Geissler; Richard J. Saykally (2005). "Unified description of temperature-dependent hydrogen bond rearrangements in liquid water" (PDF). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102 (40): 14171–14174. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10214171S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0506899102. PMC 1242322. PMID 16179387.

^ Deguchi, Shigeru; Tsujii, Kaoru (2007-06-19). "Supercritical water: a fascinating medium for soft matter". Soft Matter. 3 (7): 797. Bibcode:2007SMat....3..797D. doi:10.1039/b611584e. ISSN 1744-6848.

^ Rhein, M.; Rintoul, S.R. (2013). "3: Observations: Ocean" (PDF). IPCC WGI AR5 (Report). p. 257.Ocean warming dominates the global energy change inventory. Warming of the ocean accounts for about 93% of the increase in the Earth's energy inventory between 1971 and 2010 (high confidence), with warming of the upper (0 to 700 m) ocean accounting for about 64% of the total. Melting ice (including Arctic sea ice, ice sheets and glaciers) and warming of the continents and atmosphere account for the remainder of the change in energy.

^ Lide 2003, Chapter 6: Properties of Ice and Supercooled Water.

^ Lide 2003, 6. Properties of Water and Steam as a Function of Temperature and Pressure.

^ "Decree on weights and measures". April 7, 1795.Gramme, le poids absolu d'un volume d'eau pure égal au cube de la centième partie du mètre, et à la température de la glace fondante.

^ abcd Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997, p. 625.

^ Shell, Scott M.; Debenedetti, Pablo G.; Panagiotopoulos, Athanassios Z. (2002). "Molecular structural order and anomalies in liquid silica" (PDF). Phys. Rev. E. 66 (1): 011202. arXiv:cond-mat/0203383. Bibcode:2002PhRvE..66a1202S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.66.011202. PMID 12241346.

^ abcde Perlman, Howard. "Water Density". The USGS Water Science School. Retrieved 2016-06-03.

^

Bullis, W. Murray (1990). "Chapter 6". In O'Mara, William C.; Herring, Robert B.; Hunt, Lee P. Handbook of semiconductor silicon technology. Park Ridge, New Jersey: Noyes Publications. p. 431. ISBN 0-8155-1237-6. Retrieved 2010-07-11.

^ Loerting, Thomas; Salzmann, Christoph; Kohl, Ingrid; Mayer, Erwin; Hallbrucker, Andreas (2001-01-01). "A second distinct structural "state" of high-density amorphous ice at 77 K and 1 bar". Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 3 (24): 5355–5357. Bibcode:2001PCCP....3.5355L. doi:10.1039/b108676f. ISSN 1463-9084.

^ Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997, p. 624.

^ Zumdahl & Zumdahl 2013, p. 493.

^ abc "Can the ocean freeze?". National Ocean Service. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2016-06-09.

^ Fine, R.A.; Millero, F.J. (1973). "Compressibility of water as a function of temperature and pressure". Journal of Chemical Physics. 59 (10): 5529. Bibcode:1973JChPh..59.5529F. doi:10.1063/1.1679903.

^ "Base unit definitions: Kelvin". National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

^ ab Weingärtner et al. 2016, p. 5.

^ Proceedings of the 106th meeting (PDF). International Committee for Weights and Measures. Sèvres. 16–20 October 2017.

^ Schlüter, Oliver (2003-07-28). "Impact of High Pressure — Low Temperature Processes on Cellular Materials Related to Foods" (PDF). Technischen Universität Berlin. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-03-09.

^ Tammann, Gustav H.J.A (1925). "The States Of Aggregation". Constable And Company.

^ Lewis & Rice 1922.

^ Murphy, D. M. (2005). "Review of the vapour pressures of ice and supercooled water for atmospheric applications". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. 131 (608): 1539–1565. Bibcode:2005QJRMS.131.1539M. doi:10.1256/qj.04.94.

^ Debenedetti, P. G.; Stanley, H. E. (2003). "Supercooled and Glassy Water" (PDF). Physics Today. 56 (6): 40–46. Bibcode:2003PhT....56f..40D. doi:10.1063/1.1595053.

^ Sharp 1988, p. 27.

^ "Revised Release on the Pressure along the Melting and Sublimation Curves of Ordinary Water Substance" (PDF). IAPWS. September 2011. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

^ ab Light, Truman S.; Licht, Stuart; Bevilacqua, Anthony C.; Morash, Kenneth R. (2005-01-01). "The Fundamental Conductivity and Resistivity of Water". Electrochemical and Solid-State Letters. 8 (1): E16–E19. doi:10.1149/1.1836121. ISSN 1099-0062.

^

Crofts, A. (1996). "Lecture 12: Proton Conduction, Stoichiometry". University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

^ Hoy, AR; Bunker, PR (1979). "A precise solution of the rotation bending Schrödinger equation for a triatomic molecule with application to the water molecule". Journal of Molecular Spectroscopy. 74 (1): 1–8. Bibcode:1979JMoSp..74....1H. doi:10.1016/0022-2852(79)90019-5.

^ Zumdahl & Zumdahl 2013, p. 393.

^ Campbell & Farrell 2007, pp. 37–38.

^ Campbell & Reece 2009, p. 47.

^ Chiavazzo, Eliodoro; Fasano, Matteo; Asinari, Pietro; Decuzzi, Paolo (2014). "Scaling behaviour for the water transport in nanoconfined geometries". Nature Communications. 5: 4565. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5E4565C. doi:10.1038/ncomms4565. PMC 3988813. PMID 24699509.

^ "Physical Forces Organizing Biomolecules" (PDF). Biophysical Society. Archived from the original on August 7, 2007.CS1 maint: Unfit url (link)

^ Lide 2003, Surface Tension of Common Liquids.

^ abc Reece et al. 2013, p. 46.

^ Zumdahl & Zumdahl 2013, pp. 458–459.

^ Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997, p. 627.

^ Zumdahl & Zumdahl 2013, p. 518.

^ Pugliano, N. (1992-11-01). "Vibration-Rotation-Tunneling Dynamics in Small Water Clusters". Lawrence Berkeley Lab., CA (United States): 6. doi:10.2172/6642535.

^ Richardson, Jeremy O.; Pérez, Cristóbal; Lobsiger, Simon; Reid, Adam A.; Temelso, Berhane; Shields, George C.; Kisiel, Zbigniew; Wales, David J.; Pate, Brooks H. (2016-03-18). "Concerted hydrogen-bond breaking by quantum tunneling in the water hexamer prism". Science. 351 (6279): 1310–1313. Bibcode:2016Sci...351.1310R. doi:10.1126/science.aae0012. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 26989250.

^ Kolesnikov, Alexander I. (2016-04-22). "Quantum Tunneling of Water in Beryl: A New State of the Water Molecule". Physical Review Letters. 116 (16): 167802. Bibcode:2016PhRvL.116p7802K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.167802. PMID 27152824.

^ Pope; Fry (1996). "Absorption spectrum (380-700nm) of pure water. II. Integrating cavity measurements". Applied Optics. 36 (33): 8710–23. Bibcode:1997ApOpt..36.8710P. doi:10.1364/ao.36.008710. PMID 18264420.

^ Ball, Philip (2008). "Water—an enduring mystery". Nature. 452 (7185): 291–292. Bibcode:2008Natur.452..291B. doi:10.1038/452291a. PMID 18354466.

^ Boyd 2000, p. 105.

^ Boyd 2000, p. 106.

^ "Guideline on the Use of Fundamental Physical Constants and Basic Constants of Water" (PDF). IAPWS. 2001.

^ Hardy, Edme H.; Zygar, Astrid; Zeidler, Manfred D.; Holz, Manfred; Sacher, Frank D. (2001). "Isotope effect on the translational and rotational motion in liquid water and ammonia". J. Chem. Phys. 114 (7): 3174–3181. Bibcode:2001JChPh.114.3174H. doi:10.1063/1.1340584.

^ Urey, Harold C.; et al. (15 Mar 1935). "Concerning the Taste of Heavy Water". Science. 81 (2098). New York: The Science Press. p. 273. Bibcode:1935Sci....81..273U. doi:10.1126/science.81.2098.273-a.

^ "Experimenter Drinks 'Heavy Water' at $5,000 a Quart". Popular Science Monthly. 126 (4). New York: Popular Science Publishing. Apr 1935. p. 17. Retrieved 7 Jan 2011.

^ Müller, Grover C. (June 1937). "Is 'Heavy Water' the Fountain of Youth?". Popular Science Monthly. 130 (6). New York: Popular Science Publishing. pp. 22–23. Retrieved 7 Jan 2011.

^ Miller, Inglis J., Jr.; Mooser, Gregory (Jul 1979). "Taste Responses to Deuterium Oxide". Physiology & Behavior. 23 (1): 69–74. doi:10.1016/0031-9384(79)90124-0.

^ Weingärtner et al. 2016, p. 29.

^ Zumdahl & Zumdahl 2013, p. 659.

^ ab Zumdahl & Zumdahl 2013, p. 654.

^ Zumdahl & Zumdahl 2013, p. 984.

^ Zumdahl & Zumdahl 2013, p. 171.

^ "Hydrides". Chemwiki. UC Davis. Retrieved 2016-06-25.

^ Zumdahl & Zumdahl 2013, pp. 932, 936.

^ Zumdahl & Zumdahl 2013, p. 338.

^ Zumdahl & Zumdahl 2013, p. 862.

^ Zumdahl & Zumdahl 2013, p. 981.

^ Charlot 2007, p. 275.

^ ab Zumdahl & Zumdahl 2013, p. 866.

^ ab Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997, p. 601.

^ "Enterprise and electrolysis..." Royal Society of Chemistry. August 2003. Retrieved 2016-06-24.

^ "Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac, French chemist (1778–1850)". 1902 Encyclopedia. Footnote 122-1. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

^ Lewis, G. N.; MacDonald, R. T. (1933). "Concentration of H2 Isotope". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 1 (6): 341. Bibcode:1933JChPh...1..341L. doi:10.1063/1.1749300.

^ ab Leigh, Favre & Metanomski 1998, p. 34.

^ IUPAC 2005, p. 85.

^ Leigh, Favre & Metanomski 1998, p. 99.

^ "Tetrahydropyran". Pubchem. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2016-07-31.

^ Leigh, Favre & Metanomski 1998, pp. 27–28.

^ "Compound Summary for CID 22247451". Pubchem Compound Database. National Center for Biotechnology Information.

Bibliography

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Boyd, Claude E. (2000). "pH, Carbon Dioxide, and Alkalinity". Water Quality. Boston, Massachusetts: Springer. pp. 105–122. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-4485-2_7. ISBN 9781461544852.

Campbell, Mary K.; Farrell, Shawn O. (2007). Biochemistry (6th ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-495-39041-1.

Campbell, Neil A.; Reece, Jane B. (2009). Biology (8th ed.). Pearson. ISBN 978-0-8053-6844-4.

Campbell, Neil A.; Williamson, Brad; Heyden, Robin J. (2006). Biology: Exploring Life. Boston, Massachusetts: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-250882-7.

Charlot, G. (2007). Qualitative Inorganic Analysis. Read Books. ISBN 978-1-4067-4789-8.

Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (2005-11-22). Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry: IUPAC Recommendations 2005 (PDF). Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 978-0-85404-438-2. Retrieved 2016-07-31.

Leigh, G. J.; Favre, H. A; Metanomski, W. V. (1998). Principles of chemical nomenclature: a guide to IUPAC recommendations (PDF). Oxford: Blackwell Science. ISBN 978-0-86542-685-6. OCLC 37341352. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-26.

Lewis, William C.M.; Rice, James (1922). A System of Physical Chemistry. Longmans, Green and Co.

Lide, David R. (2003-06-19). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 84th Edition. CRC Handbook. CRC Press. ISBN 9780849304842.

Reece, Jane B.; Urry, Lisa A.; Cain, Michael L.; Wasserman, Steven A.; Minorsky, Peter V.; Jackson, Robert B. (2013-11-10). Campbell Biology (10th ed.). Boston, Mass.: Pearson. ISBN 9780321775658.

Riddick, John (1970). Organic Solvents Physical Properties and Methods of Purification. Techniques of Chemistry. Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 978-0471927266.

Sharp, Robert Phillip (1988-11-25). Living Ice: Understanding Glaciers and Glaciation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-33009-1.

Weingärtner, Hermann; Teermann, Ilka; Borchers, Ulrich; Balsaa, Peter; Lutze, Holger V.; Schmidt, Torsten C.; Franck, Ernst Ulrich; Wiegand, Gabriele; Dahmen, Nicolaus; Schwedt, Georg; Frimmel, Fritz H.; Gordalla, Birgit C. (2016). "Water, 1. Properties, Analysis, and Hydrological Cycle". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. doi:10.1002/14356007.a28_001.pub3. ISBN 9783527306732.

Zumdahl, Steven S.; Zumdahl, Susan A. (2013). Chemistry (9th ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-13-361109-7.

Further reading

Ben-Naim, A. (2011), Molecular Theory of Water and Aqueous Solutions, World Scientific

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Water molecule. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Water. |

"Water Properties and Measurements". usgs.gov. United States Geological Survey. May 2, 2016. Retrieved August 31, 2016.

Release on the IAPWS Formulation 1995 for the Thermodynamic Properties of Ordinary Water Substance for General and Scientific Use (simpler formulation)- Online calculator using the IAPWS Supplementary Release on Properties of Liquid Water at 0.1 MPa, September 2008

Chaplin, Martin. "Water Structure and Science". London South Bank University. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- Calculation of vapor pressure, liquid density, dynamic liquid viscosity, surface tension of water

- Water Density Calculator

Why does ice float in my drink?, NASA

![]() Wikiversity has small "student" steam tables suitable for classroom use.

Wikiversity has small "student" steam tables suitable for classroom use.

Comments

Post a Comment