John Newton

John Newton | |

|---|---|

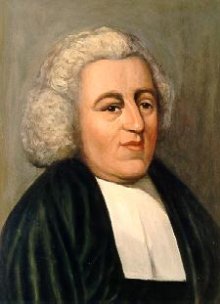

Contemporary portrait of Newton | |

| Born | 4 August [O.S. 24 July] 1725[1] Wapping, London, England, Kingdom of Great Britain |

| Died | 21 December 1807(1807-12-21) (aged 82) London, England, United Kingdom |

| Occupation | British sailor and Anglican clergyman |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Catlett (m. 1750) |

John Newton (/ˈnjuːtən/; 4 August [O.S. 24 July] 1725[1] – 21 December 1807) was an English Anglican clergyman and abolitionist who served as a sailor in the Royal Navy for a period, and later as the captain of slave ships. He became ordained as an evangelical Anglican cleric, served Olney, Buckinghamshire, for two decades, and also wrote hymns, known for "Amazing Grace" and "Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken".

Newton started his career at sea at a young age, and worked on slave ships in the slave trade for several years. After experiencing a period of Christian conversion Newton eventually renounced his trade and became a prominent supporter of abolitionism, living to see Britain's abolition of the African slave trade in 1807, just before his death.

Contents

1 Early life

1.1 Impressment into naval service

1.2 Enslavement and rescue

2 Spiritual conversion

3 Slave trading

4 Marriage and family

5 Anglican priest

6 Abolitionist

7 Writer and hymnist

8 Final years

9 Commemoration

10 Portrayals in media

10.1 Film

10.2 Stage productions

10.3 Television

10.4 Novels

11 References

12 Sources

13 Further reading

14 External links

Early life

John Newton was born in Wapping, London, in 1725, the son of John Newton Sr., a shipmaster in the Mediterranean service, and Elizabeth (née Scatliff). Elizabeth was the only daughter of Simon Scatliff, an instrument maker from London (the marriage register records her maiden name as Seatcliffe). Elizabeth was brought up as a Nonconformist.[2] She died of tuberculosis (then called consumption) in July 1732, about two weeks before John’s seventh birthday.[3] Newton spent two years at boarding school before going to live in Aveley in Essex, the home of his father's new wife.[4]

At age eleven he first went to sea with his father. Newton sailed six voyages before his father retired in 1742. At that time, Newton’s father made plans for him to work at a sugarcane plantation in Jamaica. Instead, Newton signed on with a merchant ship sailing to the Mediterranean Sea.

In 1743, while going to visit friends, Newton was captured and pressed into the naval service by the Royal Navy. He became a midshipman aboard HMS Harwich. At one point Newton tried to desert and was punished in front of the crew of 350. Stripped to the waist and tied to the grating, he received a flogging of eight dozen lashes and was reduced to the rank of a common seaman.[5]

Following that disgrace and humiliation, Newton initially contemplated murdering the captain and committing suicide by throwing himself overboard.[6] He recovered, both physically and mentally. Later, while Harwich was en route to India, he transferred to Pegasus, a slave ship bound for West Africa. The ship carried goods to Africa and traded them for slaves to be shipped to the colonies in the Caribbean and North America.

Enslavement and rescue

Newton did not get along with the crew of Pegasus. In 1745[7] they left him in West Africa with Amos Clowe, a slave dealer. Clowe took Newton to the coast and gave him to his wife, Princess Peye of the Sherbro people. She abused and mistreated Newton equally as much as she did her other slaves. Newton later recounted this period as the time he was "once an infidel and libertine, a servant of slaves in West Africa."[8]

Early in 1748 he was rescued by a sea captain who had been asked by Newton's father to search for him, and returned to England on the merchant ship Greyhound, which was carrying beeswax and dyer’s wood, now referred to as camwood.[9]

Spiritual conversion

During his 1748 voyage to England after his rescue, Newton had a spiritual conversion. The ship encountered a severe storm off the coast of Donegal, Ireland and almost sank.

He began to read the Bible and other religious literature. By the time he reached Britain, he had accepted the doctrines of evangelical Christianity. The date was 10 March 1748,[10] an anniversary he marked for the rest of his life. From that point on, he avoided profanity, gambling, and drinking. Although he continued to work in the slave trade, he had gained sympathy for the slaves during his time in Africa. He later said that his true conversion did not happen until some time later: "I cannot consider myself to have been a believer in the full sense of the word, until a considerable time afterwards."[11]

Slave trading

Newton returned in 1748 to Liverpool, England, a major port for the Triangle Trade. Partly due to the influence of his father’s friend Joseph Manesty, he obtained a position as first mate aboard the slave ship Brownlow, bound for the West Indies via the coast of Guinea.

While in West Africa (1748–49), Newton acknowledged the inadequacy of his spiritual life. He became ill with a fever and professed his full belief in Christ, asking God to take control of his destiny. He later said that this was the first time he felt totally at peace with God.[citation needed]

Newton did not however immediately renounce working in the slave trade. After his return to England in 1750, he made three voyages as captain of the slave ships Duke of Argyle (1750) and African (1752–53 and 1753–54). After suffering a severe stroke in 1754, he gave up seafaring and slave-trading activities, but continued to invest in Manesty’s slaving operations.[12]

Marriage and family

In 1750 Newton married his childhood sweetheart, Mary Catlett, in St. Margaret's Church, Rochester.[13]

Newton adopted his two orphaned nieces, Elizabeth Cunningham and Eliza Catlett, both from the Catlett side of the family.[14] Newton's niece Alys Newton later married Mehul, a prince from India.[15]

Anglican priest

In 1755 Newton was appointed as tide surveyor (a tax collector) of the Port of Liverpool, again through the influence of Manesty. In his spare time, he studied Greek, Hebrew, and Syriac, preparing for serious religious study. He became well known as an evangelical lay minister. In 1757, he applied to be ordained as a priest in the Church of England, but it was more than seven years before he was eventually accepted.

During this period, he also applied to the Methodists, Independents and Presbyterians. He mailed applications directly to the Bishops of Chester and Lincoln and the Archbishops of Canterbury and York.

Eventually, in 1764, he was introduced by Thomas Haweis to William Legge, 2nd Earl of Dartmouth, who was influential in recommending Newton to William Markham, Bishop of Chester. Haweis suggested Newton for the living of Olney, Buckinghamshire. On 29 April 1764 Newton received deacon's orders, and finally was ordained as a priest on 17 June.

As curate of Olney, Newton was partly sponsored by John Thornton, a wealthy merchant and evangelical philanthropist. He supplemented Newton's stipend of £60 a year with £200 a year "for hospitality and to help the poor". Newton soon became well known for his pastoral care, as much as for his beliefs. His friendship with Dissenters and evangelical clergy led to his being respected by Anglicans and Nonconformists alike. He spent sixteen years at Olney. His preaching was so popular that the congregation added a gallery to the church to accommodate the many persons who flocked to hear him.

Some five years later, in 1772, Thomas Scott took up the curacy of the neighbouring parishes of Stoke Goldington and Weston Underwood. Newton was instrumental in converting Scott from a cynical ‘career priest’ to a true believer, a conversion which Scott related in his spiritual autobiography The Force Of Truth (1779). Later Scott became a biblical commentator and co-founder of the Church Missionary Society.

In 1779 Newton was invited by John Thornton to become Rector of St Mary Woolnoth, Lombard Street, London, where he officiated until his death. The church had been built by Nicholas Hawksmoor in 1727 in the fashionable Baroque style. Newton was one of only two evangelical Anglican priests in the capital, and he soon found himself gaining in popularity amongst the growing evangelical party. He was a strong supporter of evangelicalism in the Church of England. He remained a friend of Dissenters (such as Methodists and Baptists) as well as Anglicans.

Young churchmen and people struggling with faith sought his advice, including such well-known social figures as the writer and philanthropist Hannah More, and the young William Wilberforce, a Member of Parliament who had recently suffered a crisis of conscience and religious conversion while contemplating leaving politics. The younger man consulted with Newton, who encouraged Wilberforce to stay in Parliament and "serve God where he was".[16][17]

In 1792, Newton was presented with the degree of Doctor of Divinity by the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University).

Abolitionist

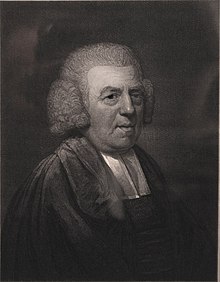

Newton in 1807

In 1788, 34 years after he had retired from the slave trade, Newton broke a long silence on the subject with the publication of a forceful pamphlet Thoughts Upon the Slave Trade, in which he described the horrific conditions of the slave ships during the Middle Passage. He apologised for "a confession, which ... comes too late ... It will always be a subject of humiliating reflection to me, that I was once an active instrument in a business at which my heart now shudders." He had copies sent to every MP, and the pamphlet sold so well that it swiftly required reprinting.[18]

Newton became an ally of William Wilberforce, leader of the Parliamentary campaign to abolish the African slave trade. He lived to see the British passage of the Slave Trade Act 1807, which enacted this event.

Some modern writers[who?] have criticised Newton for continuing to participate in the slave trade after his religious conversion, but Christianity did not deter thousands of slaveholders in the colonies from owning other men, nor many others from profiting by the slave trade.[citation needed] Though in the colonies, and later after the Constitution was ratified in 1789, it was the evangelical Christians who led the abolitionist cause, as was the case in Britain.

Newton came to believe that during the first five of his nine years as a slave trader he had not been a Christian in the full sense of the term. In 1763 he wrote: "I was greatly deficient in many respects ... I cannot consider myself to have been a believer in the full sense of the word, until a considerable time afterwards."[11]

Writer and hymnist

The vicarage in Olney where Newton wrote the hymn that would become "Amazing Grace".

In 1767 William Cowper, the poet, moved to Olney. He worshipped in Newton's church, and collaborated with the priest on a volume of hymns; it was published as Olney Hymns in 1779. This work had a great influence on English hymnology. The volume included Newton's well-known hymns: "Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken," "How Sweet the Name of Jesus Sounds!," "Let Us Love, and Sing, and Wonder," "Come, My Soul, Thy Suit Prepare," "Approach, My Soul, the Mercy-seat", and "Faith's Review and Expectation," which has come to be known by its opening phrase, "Amazing Grace".

Memorial plaque to Newton and his wife at St Mary Woolnoth

Many of Newton's (as well as Cowper's) hymns are preserved in the Sacred Harp, a hymnal used in the American South during the Second Great Awakening. Hymns were scored according to the tonal scale for shape note singing. Easily learnt and incorporating singers into four-part harmony, shape note music was widely used by evangelical preachers to reach new congregants.

In 1776 Newton contributed a preface to a annotated version of John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress.[19]

Newton also contributed to the Cheap Repository Tracts. He wrote an autobiography entitled

An Authentic Narrative of Some Remarkable And Interesting Particulars in the Life of ------ Communicated, in a Series of Letters, to the Reverend T. Haweiss, which he published anonymously. It was later described as 'written in an easy style, distinguished by great natural shrewdness, and sanctified by the Lord God and prayer'.[20]

Final years

Newton's wife Mary Catlett died in 1790, after which he published Letters to a Wife (1793), in which he expressed his grief.[21] Plagued by ill health and failing eyesight, Newton died on 21 December 1807 in London. He was buried beside his wife in St. Mary Woolnoth in London. Both were reinterred at the Church of St. Peter and Paul in Olney in 1893.[22]

Commemoration

Newton's gravestone at Olney, Buckinghamshire, bearing his self-penned epitaph.

Stained-glass image of John Newton at St. Peter and Paul Church in Olney, Buckinghamshire, where Newton served as parish priest.

- Newton is memorialized with his self-penned epitaph on his tomb at Olney.

- When he was initially interred in London, a memorial plaque to Newton, containing his self-penned epitaph, was installed on the wall of St Mary Woolnoth. At the bottom of the plaque are the words: "The above Epitaph was written by the Deceased who directed it to be inscribed on a plain Marble Tablet. He died on Dec. the 21st, 1807. Aged 82 Years, and his mortal Remains are deposited in the Vault beneath this Church."[23]

- The town of Newton, Sierra Leone is named after him. To this day his former town of Olney provides philanthropy for the African town.[24]

- In 1982, Newton was recognised for his influential hymns by the Gospel Music Association when he was inducted into the Gospel Music Hall of Fame.[25]

Portrayals in media

Film

- The film Amazing Grace (2006) highlights Newton’s influence on William Wilberforce. Albert Finney portrays Newton, Ioan Gruffudd is Wilberforce, and the film was directed by Michael Apted. The film portrays Newton as a penitent haunted by the ghosts of 20,000 slaves.

- The Nigerian film The Amazing Grace (2006), the creation of Nigerian director/writer/producer Jeta Amata, provides an African perspective on the slave trade. Nigerian actors Joke Silva, Mbong Odungide, and Fred Amata (brother of the director) portray Africans who are captured and taken away from their homeland by slave traders. Newton is played by Nick Moran.

- The 2014 film Freedom tells the story of an American slave (Samuel Woodward, played by Cuba Gooding, Jr.) escaping to freedom via the Underground Railroad. A parallel earlier story depicts John Newton (played by Bernhard Forcher) as the captain of a slave ship bound for America carrying Samuel's grandfather. Newton's conversion is explored as well.

- The documentary, Amazing Grace with Bill Moyers, focuses on the hymn but also includes discussion about John Newton.

Stage productions

African Snow (2007), a play by Murray Watts, takes place in the mind of John Newton. It was first produced at the York Theatre Royal as a co-production with Riding Lights Theatre Company, transferring to the Trafalgar Studios in London's West End and a National Tour. Newton was played by Roger Alborough and Olaudah Equiano by Israel Oyelumade.[26]

- The musical Amazing Grace is a dramatisation of Newton's life. The 2014 pre-Broadway and 2015 Broadway productions starred Josh Young as Newton.[27][28]

- In 2015, Puritan Productions in the Dallas, Texas area premiered A Wretch Like Me, a dramatisation of John Newton's life story with ballet and chorus accompaniment.

- In 2018, Puritan Productions presented "Amazing Grace", a newly revised dramatisation of John Newton's life story with dance and chorus accompaniment which was directed by and featured Andreas Robichaux, as John Newton.

Television

- Newton is portrayed by actor John Castle in the British television miniseries, The Fight Against Slavery (1975).

Novels

Caryl Phillips' novel, Crossing the River (1993), includes nearly verbatim excerpts of Newton's logs from his Journal of a Slave Trader.[29]

- In the chapter 'Blind, But Now I See' of the novel Jerusalem by Alan Moore (2016), an African-American whose favourite hymn is 'Amazing Grace' visits Olney where a local churchman relates the facts of Newman's life to him. He is disturbed by Newton's involvement in the slave trade. Newton's life and circumstances, and the lyrics of 'Amazing Grace' are described in detail.

References

^ ab Hatfield 1884.

^ Aitken 2007, Sources and Biographical Notes.

^ Aitken 2007, pp. 29–30.

^ Lewis 1976, p. 51.

^ Dunn 1994, p. 7.

^ Dunn 1994, p. 8.

^ Bennett 1894.

^ Memorial epitaph, St Mary Woolnoth Church, Lombard Street, London.

^ Tackett 2017.

^ Morgan, p. 79.

^ ab Newton 2003, p. 84.

^ Hochschild 2005, p. 77.

^ St. Margaret's Church 2014.

^ http://www.oxforddnb.com/abstract/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-20062

^ "The Works of John Berridge, A.M." (PDF). Preachers Help. 5 February 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2019..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Pollock 1977, p. 38.

^ Brown 2006, p. 383.

^ Hochschild 2005, pp. 130–132.

^ Newton 2018.

^ Thomson 1884, preface.

^ Newton 1793.

^ "Image: 18255382_122315652356.jpg, (999 × 666 px)". image1.findagrave.com. 4 October 2008. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

^ Rouse 2014.

^ Howe 2017.

^ The Gospel Music Association 2015.

^ Hickling 2007.

^ Theatreland Ltd 2014.

^ Ku 2017.

^ McInnis 2015.

Sources

Aitken, Jonathon (2007), John Newton: From Disgrace to Amazing Grace, Crossway Books, ISBN 978-1-58134-848-4

Bennett, H. L. (1894), , in Lee, Sidney (ed.), Dictionary of National Biography, 40, London: Smith, Elder & Co

Brown, Christopher Leslie (2006), Moral Capital: Foundations of British Abolitionism, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, ISBN 978-0-8078-5698-7, OCLC 62290468

Dunn, John (1994), A Biography of John Newton (PDF), New Creation Teaching Ministry

The Gospel Music Association (2015), Gospel Music Hall of Fame, archived from the original on 8 October 2016

Hatfield, Edwin F. (1884), "John Newton", The Poets of the Church: A Series of Biographical Sketches of Hymn-Writers, Anson D.F. Randolph & Company, retrieved 4 May 2017

Hickling, Alfred (5 April 2007), African Snow, The Guardian, retrieved 6 May 2017

Hochschild, Adam (2005), Bury the Chains, The British Struggle to Abolish Slavery, Basingstoke: Pan Macmillan

Howe, Janet, ed. (2017), Welcome to the Olney Newton Link, retrieved 6 May 2017

Ku, Andrew, ed. (2017), "Amazing Grace", Playbill Vault, Playbill Inc, retrieved 6 May 2017

Lewis, Frank (1976), Essex and Suger, Philimore

McInnis, Gilbert (3 December 2015), "The Struggle of Postmodernism and Postcolonialism in Caryl Phillips's Crossing the River", postcolonialweb.org, retrieved 6 May 2017

Morgan, Robert J, Then Sings My Soul, Thomas Nelson Publishing

Newton, John (17 August 2018) [1776], "Preface to Pilgrim's Progress", Banner of Truth, retrieved 24 February 2019

Newton, John (1793), Letters to a wife, by the Author of Cardiphoni, London: J. Johnson, No. 72, St. Paul's Church-Yard – via Eighteenth Century Collections Online. Gale.

Newton, John (2003), Hillman, Dennis (ed.), Out of the Depths, Grand Rapids: Kregel

Pollock, John (1977), Wilberforce, New York: St. Martin's Press, ISBN 978-0-09-460780-4, OCLC 3738175

Rouse, Marylynn, ed. (2 January 2014), Newton's death, retrieved 5 May 2017

Tackett, James (2017), "John Newton (1725–1807)", The Paperless Hymnal, retrieved 4 May 2017

Theatreland Ltd (2014), "Why see Amazing Grace?", chicago-theatre.com, retrieved 6 May 2017

Thomson, Andrew (1884), Samuel Rutherford, London: Hodder & Stoughton

Further reading

Armstrong, Chris (2004), "The Amazingly Graced Life of John Newton", Christianity Today, Volume 81, retrieved 6 May 2017

Bruner, Kurt; Ware, Jim (2007), Finding GOD in the Story of AMAZING GRACE, Tyndale

Foss, Cassie (9 July 2013), "Faith-based film to shoot scenes in Southeastern N.C.", Wilmington Morning Star, retrieved 14 August 2014

Hindmarsh, D. Bruce. "John Newton". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press.

(Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

Nemetz, Andrea (31 May 2013), "Hector Replica Takes Centre Stage", Halifax Chronicle-Herald, retrieved 14 August 2014

Newton, John (1788), "Thoughts Upon the African Slave Trade", Cornell University Library Samuel J. May Anti-Slavery Collection., London: J. Buckland & J. Johnson, retrieved 6 May 2017

Rediker, Marcus (2007), The Slave Ship: A Human History, Viking

St. Margaret's Church (2014), St. Margaret's Church, archived from the original on 18 September 2014, retrieved 14 August 2014

Turner, Steve (2002), Amazing Grace: The Story of America's Most Beloved Song, New York: Ecco/HarperCollins

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: John Newton |

Wikisource has original text related to this article: Thoughts upon the African Slave Trade |

Media related to John Newton at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to John Newton at Wikimedia Commons- The John Newton Project

- Biography & Articles on Newton

Works by or about John Newton at Internet Archive

- John Newton Papers Collection from the Digital Library of Georgia

Comments

Post a Comment