Margaret the Virgin

Saint Margaret of Antioch Saint Marina the Great Martyr | |

|---|---|

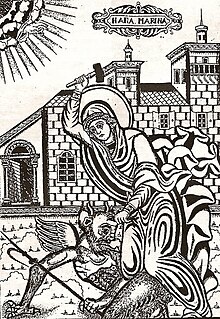

Saint Marina the Great Martyr. An illustration in her hagiography printed in Greece depicting her beating a demon with a hammer. Date on the picture: 1858. | |

| Virgin-Martyr and Vanquisher of Demons | |

| Born | 289 Antioch, Pisidia |

| Died | 304 (aged 15) |

| Feast | July 20 (Roman Catholic Church, Anglican Church,[1]Western Rite Orthodoxy) July 17 (Byzantine Christianity) Hathor 23 (Coptic Christianity) (Consecration of her Church) |

| Attributes | slain dragon (Western depictions); hammer, defeated demon (Eastern Orthodox depictions) |

| Patronage | childbirth, pregnant women, dying people, kidney disease, peasants, exiles, falsely accused people; Lowestoft, England; Queens' College, Cambridge; nurses; Sannat and Bormla, Malta |

Catholic cult suppressed | 1969[2] by Pope Paul VI |

Margaret, known as Margaret of Antioch in the West, and as Saint Marina the Great Martyr (Greek: Ἁγία Μαρίνα) in the East, is celebrated as a saint on July 20 in the Western Rite Orthodox, Roman Catholic and Anglican Churches, on July 17 (Julian calendar) by the Eastern-Rite Orthodox Church and on Epip 23 and Hathor 23 in the Coptic Churches.[3]

Said to have been martyred in 304, she was declared apocryphal by Pope Gelasius I in 494, but devotion to her revived in the West with the Crusades.

She was reputed to have promised very powerful indulgences to those who wrote or read her life, or invoked her intercessions; these no doubt helped the spread of her cultus.[4]

Margaret is one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers, and is one of the saints who spoke to Joan of Arc.

Contents

1 Hagiography

2 Veneration

3 Iconography

4 See also

5 References

5.1 Sources

6 External links

Hagiography

According to the version of the story in Golden Legend, she was a native of Antioch and the daughter of a pagan priest named Aedesius. Her mother having died soon after her birth, Margaret was nursed by a Christian woman five or six leagues (6.9–8.3 miles) from Antioch.

Having embraced Christianity and consecrated her virginity to God, Margaret was disowned by her father, adopted by her nurse, and lived in the country keeping sheep with her foster mother (in what is now Turkey).[5] Olybrius, Governor of the Roman Diocese of the East, asked to marry her, but with the demand that she renounce Christianity. Upon her refusal, she was cruelly tortured, during which various miraculous incidents occurred.

One of these involved being swallowed by Satan in the shape of a dragon, from which she escaped alive when the cross she carried irritated the dragon's innards.

The Golden Legend describes this last incident as "apocryphal and not to be taken seriously" (trans. Ryan, 1.369).

As Saint Marina, she is associated with the sea, which "may in turn point to an older goddess tradition", reflecting the pagan divinity, Aphrodite.[6]

Veneration

The Eastern Orthodox Church knows Margaret as Saint Marina, and celebrates her feast day on July 20th. She has been identified with Saint Pelagia, "Marina" being the Latin equivalent of the Greek "Pelagia" who—according to her hagiography by James, the deacon of Heliopolis—had been known as "Margarita" ("Pearl"). We possess no historical documents on Saint Margaret as distinct from Saint Pelagia. The Greek Marina came from Antioch in Pisidia (as opposed to Antioch of Syria), but this distinction was lost in the West.

The story was summarized in the 9th-century martyrology of Rabanus Maurus, even if it was too fantastic for many clergy (it went too far even for Jacobus de Voragine, who remarks that the part where she is eaten by the dragon is to be considered apocryphal).[7]

In 1222, the Council of Oxford added her to the list of feast days, and so her cult acquired great popularity. Many versions of the story were told in 13th-century England, in Anglo-Norman (including one ascribed to Nicholas Bozon), English, and Latin,[8] and more than 250 churches are dedicated to her in England, most famously, St. Margaret's, Westminster, the parish church[9] of the British Houses of Parliament in London.

In art, she is usually pictured escaping from, or standing above, a dragon.

She is recognized as a saint by the Roman Catholic Church, being listed as such in the Roman Martyrology for July 20.[10]

She was also included from the 12th to the 20th century among the saints to be commemorated wherever the Roman Rite was celebrated,[11] but was then removed from that list because of the entirely fabulous character of the stories told of her.[12]

Every year on Epip 23 the Coptic Orthodox church celebrates her martyrdom day,[3] and on Hathor 23 the Coptic church celebrates the dedication of a church to her name.

Saint Mary church in Cairo still keeps her right hand until now after it was moved from the Angel Michael Church at Alvhadin (nowadays Haret Al Gawayna) following its destruction in the 13th century AD. It is displayed to the public and visitors on her feast days.[citation needed]

Iconography

Saint Margaret and the Dragon, alabaster with traces of gilding, Toulouse (ca 1475). (Metropolitan Museum of Art). |  Reliquary Bust of Saint Margaret of Antioch. Attributed to Nikolaus Gerhaert (active in Germany, 1462 - 73). |  Saint Margaret of Antioch, limestone with paint and gilding, Burgos, (ca. 1275-1325). (Metropolitan Museum of Art). |  Saint Margaret as a shepherdess by Francisco de Zurbarán, (1631). |  Saint Margaret of Antioch by Peter Candid (second half of the 16th century) |  Margaret the Virgin on a painting in the Novacella Abbey, Neustift, South Tyrol, Italy. |  Saint Margaret attracts the attention of the Roman prefect, by Jean Fouquet, (from an illuminated manuscript). |

See also

Saint Marina the Monk and Saint Pelagia, both of whom are sometimes conflated or confused with Margaret

References

^ Book of Common Prayer

^ Mary Clayton; Hugh Magennis (15 September 1994). The Old English Lives of St. Margaret. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-521-43382-2..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab "23 أبيب - اليوم الثالث والعشرين من شهر أبيب - السنكسار". St-takla.org. 2014-10-11. Retrieved 2018-05-02.

[unreliable source?]

^ "Margaret of Antioch". The Oxford Dictionary of Saints. David Hugh Farmer. Oxford University Press, 2003. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. Accessed 16 June 2007

^ MacRory, Joseph. "St. Margaret." The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 1 Mar. 2013

^ Gábor Klaniczay; Éva Pócs; Eszter Csonka-Takacs (2006). Christian Demonology and Popular Mythology. Central European University Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-963-7326-76-9.

^ de Voragine, Jacobus (1993). The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints. 1. Translated by Ryan, William Granger. Princeton UP. pp. 368–70.

^ Jones, Timothy (1994). "Geoffrey of Monmouth, "Fouke le Fitz Waryn," and National Mythology". Studies in Philology. 91 (3): 233–249. JSTOR 4174487.

^ Westminster Abbey. "St. Margaret's, Westminster Parish details". Archived from the original on 2008-03-05. Retrieved 2008-05-03.

^ Martyrologium Romanum (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2001

ISBN 88-209-7210-7)

^ See General Roman Calendar as in 1954

^ Calendarium Romanum (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1969), p. 130

Sources

Acta Sanctorum, July, v. 24–45

Bibliotheca hagiographica. La/ma (Brussels, 1899), n. 5303–53r3- Frances Arnold-Forster, Studies in Church Dedications (London, 1899), i. 131–133 and iii. 19.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 700.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 700.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Saint Margaret of Antioch. |

- Saint Margaret and the Dragon links

Middle English life of St. Margaret of Antioch, edited with notes by Sherry L. Reames

Book of the Passion of Saint Margaret the Virgin, with the Life of Saint Agnes, and Prayers to Jesus Christ and to the Virgin Mary (in English) (in Latin) (in Italian)

- Catholic Online: Saint Margareth of Antioch

- The Life of St. Margaret of Antioch

Comments

Post a Comment