North River (Hudson River)

North River in red, if defined as portion between New Jersey and Manhattan.

Looking south from atop the Hudson Palisades

North River is an alternative name for the southernmost portion of the Hudson River in the vicinity of New York City and northeastern New Jersey in the United States.[1][2][3][4][5][6] The colonial name for the entire Hudson was given to it by the Dutch in the early seventeenth century; the term fell out of general use for most of the river's 300+ mile course during the early 1900s.[7] However it still retains currency as an alternate or additional name among local mariners and others[8][9][10] as well as appearing on some nautical charts[11] and maps. The term is used for infrastructure on and under the river, such as the North River piers, North River Tunnels, and the North River Wastewater Treatment Plant.

Flight 1549 landing on the waters of the North River

At different times "North River" has referred to

- the entire Hudson

- the approximate 160-mile portion of the Hudson below its confluence with the Mohawk River, which is under tidal influence

- the portion of it running between Manhattan and New Jersey[12]

- the length flowing between Lower Manhattan and Hudson County, New Jersey.

Its history is strongly connected to shipping industry in the Port of New York and New Jersey, which shifted primarily to Port Newark in the mid-20th century due to the construction of the Holland Tunnel and other river crossings and the advent of containerization.[13]

The names for the lower portion of the river appear to have remained interchangeable for centuries. In 1909, two tunnels were under construction: one was called the North River Tunnels, the other, the Hudson Tubes. That year the Hudson–Fulton Celebration was held, commemorating Henry Hudson, the first European to record navigating the river, and Robert Fulton, the first man to use a paddle steamer in America, named the North River Steamboat, to sail up it, leading to controversy over what the waterway should be called.[14][15][16]

Much of the shoreline previously used for maritime, rail, and industrial activities has given way to recreational promenades and piers. On the Hudson Waterfront in New Jersey, the Hudson River Waterfront Walkway runs for about 18 miles. In Manhattan, the Hudson River Park runs from Battery Park to 59th Street.

Contents

1 Origin of the name and early usage

1.1 "North River" on maps

2 North River piers

2.1 Historical and current use

3 Railroads and ferries

4 Fixed crossings

5 See also

6 References

7 Further reading

Origin of the name and early usage

Revolutionary-era map using both names

The origin of the name North River is generally attributed to the Dutch.[17] In describing the major rivers in the New Netherland colony, they called what is now the Hudson the North River, the Connecticut the Fresh River, and the Delaware the South River.[18] Another theory is that the "North" River and "East" River were so named for the direction of travel they permitted once having entered the Upper New York Bay.[19]

In 1808 the Secretary of the Treasury, Albert Gallatin, issued his report of proposed locations for transportation and communication internal improvements of national importance. The North River figures prominently among his proposals as the best route toward western and northern lands; similar routes were chosen for the Erie Canal and other early canals built by the state of New York. He notes the following in reference to the North and Hudson Rivers:[20]

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

What is called the North River is a narrow and long bay, which in its northwardly course from the harbor of New York breaks through or turns all the mountains, affording a tide navigation for vessels of eighty tons to Albany and Troy, one hundred and sixty miles above New York. This peculiarity distinguishes the North River from all the other bays and rivers of the United States. The tide in no other ascends higher than the granite ridge or comes within thirty miles of the Blue Ridge or eastern chain of mountains. In the North River it breaks through the Blue Ridge at West Point and ascends above the eastern termination of the Catskill or great western chain.

A few miles above Troy, and the head of the tide, the Hudson from the north and the Mohawk from the west unite their waters and form the North River. The Hudson in its course upwards approaches the waters of Lake Champlain, and the Mohawk those of Lake Ontario.

"North River" on maps

North River on a 1997 Hagstrom Map of Manhattan, sited between Hudson County, New Jersey and Lower Manhattan

Hagstrom Maps, formerly the leading mapmaker in the New York metropolitan area, has labeled all or part of the Hudson adjacent to Manhattan as "North River" on several of its maps. For instance, on a 1997 Hagstrom Map of Manhattan, the stretch of river between Hudson County, New Jersey and Lower Manhattan (roughly corresponding to the location of the North River piers) was labeled "North River", with the label "Hudson River" used above Midtown Manhattan.

On a 2000 map of "Northern Approaches to New York City" (part of Hagstrom's New York [State] Road Map), the entire river adjacent to Manhattan was labeled "Hudson River (North River)", with just "Hudson River" (no parenthetical) appearing further north at Tappan Zee. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's current charts call the lower river the "Hudson",[21] and the United States Geological Survey lists "North River" as an alternative name of the Hudson River without qualifying it as any particular portion of the river.[22]

North River piers

Lower Manhattan circa 1931. East River piers are in the foreground; the North River and North River piers stretch off into the background.

Piers along the Hudson shore of Manhattan were formerly used for shipping and berthing ocean-going ships.[23] In shipping notices, they were designated as, for example, "Pier 14, North River". As with the river, the name "North River piers" has largely been supplanted by "Hudson River piers", or just by a pier and number, e.g., "Pier 54". Piers above Pier 40 have addresses approximately that of Manhattan's numbered streets plus 40 – thus, for example, North River Pier 86 is at West 46th Street.

Most of the piers that once existed in lower Manhattan fell into disuse or were destroyed in the last half of the 20th century. The remaining piers are Pier A at the Battery and piers ranging from Pier 25 at North Moore Street to Pier 99 at 59th Street. Many of these piers and the waterfront between them are part of the Hudson River Park which stretches from 59th Street to the Battery. The park, a joint project between New York City and New York State commenced in 1998, consists of several non-contiguous parcels of land and piers totaling 125 acres (0.51 km2), plus another 400 acres (1.6 km2) of the river itself.[24] Several piers were rebuilt for adaptive re-use as part of the park project, with approximately 70% of the planned work complete by 2011.[25]

Historical and current use

Chelsea Piers, with the Lusitania docked, circa 1910

Rebuilding of Pier 97

Javits Center, behind which is located New York Waterway's Midtown Ferry Terminal at Pier 79. The Weehawken Yards were at the base of the Hudson Palisades.

Pier A is a designated national and New York City landmark. The building on the pier dates to 1886, and was used by the city's Department of Docks, Harbor Police, and was later a fireboat station. The pier was closed and renovated from 1992 to November 2014, after which it reopened.- What little remained of Piers 1 through 21 were buried under landfill from the World Trade Center construction project in 1973 and turned into Battery Park City.

- Pier 25 is a sports and docking facility at the foot of North Moore Street and part of Hudson River Park.[26]

- Pier 26 was rebuilt over 2008-2009 and a new park designed by OLIN and Rafael Viñoly is currently under construction, set to open in fall 2020.[27]

- Pier 34 is a pair of narrow piers which connect to a ventilation building for the Holland Tunnel.

Pier 40 contains various playing fields, long-term parking spaces and the Trapeze School of New York on the roof (during the summer).

Christopher Street Pier is part of Hudson River Park.- Pier 51 houses water-themed playgrounds, part of Hudson River Park.[28]

- Pier 52 and 53, opposite Gansevoort Street, form the "Gansevoort Peninsula", created with landfill. This peninsula is home to the last vestige of what was once Thirteenth Avenue in Manhattan. The peninsula is currently a Sanitation Department storage and parking facility. At the end of Pier 53 is the FDNY's Marine 1 fireboat facility. The facility occupies a new building completed in 2011.[29][30]

- Pier 55 is not in use. Plans arose in November 2014 for a new park designed by Heatherwick Studio, with estimates of the 2.3 acres (0.93 ha) park between $130 million[31] and $160 million.[32] Major backers included Barry Diller and Diane von Fürstenberg's joint foundation, which contributed $100 million to the project[31] with plans to give up to $130 million.[33] The city and state vowed to give $17 million and $18 million, respectively.[32] The park, a partnership between Diller and von Furstenberg's foundation, the city and state, and Hudson River Park Trust, was to float above the water on 300 concrete pillars.[33] In September 2017, plans for the park were scrapped after legal challenges and rising cost estimates.[34] In October 2017, the proposal was revived in exchange for Governor Andrew Cuomo agreeing to complete the remaining 30% of the incomplete Hudson River Park.[35]

Pier 57 was built to a unique concrete design in 1952 to replace a burned wooden structure. It has served as a shipping terminal and a bus depot, but has been vacant since 2003. It is currently under development as a commercial and retail complex anticipated to re-open in 2018.- The Chelsea Piers entertainment complex is located at piers 59 through 62, from West 17th to West 22nd Street. In the early 1900s, Chelsea Piers was used by the Cunard and White Star lines, and was the intended destination of the Titanic as well as the final berth of the Lusitania.

Pier 63 was the location of a barge formerly serving the Erie-Lackawanna Railroad, now situated at Pier 66a.

Pier 66 has a public boathouse and is also the home of Pier 66 Maritime.- Pier 76 is home to New York City car tow pound for Manhattan.[36]

- Pier 78 is used by NY Waterway.[37]

- Pier 79 is the West Midtown Ferry Terminal, used by NY Waterway. Pier 79 connects to a Lincoln Tunnel vent shaft.

- Pier 83 is used by Circle Line Sightseeing Cruises.

- Pier 84 is a stop for New York Water Taxi and has a bicycle rental shop and other businesses serving primarily tourists as well as a playground.[38]

- Pier 86 is home to the Intrepid Sea-Air-Space Museum, the centerpiece of which is the USS Intrepid, an aircraft carrier that served from World War II to the Vietnam War. This pier once served as the passenger ship terminal for the United States Lines.

- Piers 88 through 90 are part of the New York Passenger Ship Terminal, where a number of modern cruise ships and ocean liners dock. In 1942, the USS Lafayette (formerly SS Normandie) caught fire at Pier 88, remaining capsized there for a year.

- Piers 92 and 94 were formerly part of the Passenger Ship Terminal and now house a convention center, currently the second-largest exhibition hall in New York City.[39]

- Piers 96 and 97 are part of Hudson River Park.

- Pier 98 is used for Con Edison employee car parking, a training facility and delivery by barge and storage of fuel oil.

- Pier 99 houses the West 59th Street Marine Transfer Station, used by the New York City Sanitation Department.

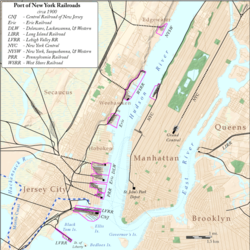

Railroads and ferries

Railroad and ferry terminals along the North River circa 1900

Prior to the opening of the North River Tunnels and the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad tubes in the early 1900s,[40] passengers and freight were required to cross the river for travel to points east. This led to an extensive network of intermodal terminals, railyards, ferry slips, docks, barges, and carfloats. The west shore of the river from the mid 19th to the mid 20th century was home to expansive facilities operated by competing railroads.[41] Most are now gone, allowing for public access to the waterfront at piers, parks, promenades and marinas along the Hudson River Waterfront Walkway. New ferry slips and terminals exclusively for pedestrian use have been built.

Communipaw Terminal was in operation from 1864 to 1967. It was owned by the Central Railroad of New Jersey and also hosted trains of the Baltimore and Ohio and the Reading Company. The CRRNJ's main ferry ran to pier 11 at Liberty Street. The historic landmark is now a major feature of Liberty State Park and ferry terminal for service to Ellis Island and Liberty Island. The terminal is adjacent to the Big Basin of the Morris Canal (used to ship anthracite from the mines of Pennsylvania) which entered the harbor at the river's mouth.

Pennsylvania Railroad Station was the location of the first waterfront terminal in 1834, and its larger successor was used until 1961. Regular ferry service from Paulus Hook had begun in the early Dutch colonial period. The original station was built by the New Jersey Railroad to meet the world's first steam ferry service which had been initiated in 1812 by Robert Fulton and Robert Livingston. During the Pennsylvania Railroad era in the 20th century the station was called Exchange Place, local nomenclature for the streetcar terminus and Hudson and Manhattan Railroad tube station. The main ferry ran to Cortlandt Street. The district is now sometimes known as Wall Street West due to the concentration of financial concerns and skyscrapers located there. Today ferry service travel to Battery Park City Ferry Terminal, Pier 11 at Wall Street, and the West Midtown Ferry Terminal.

Pavonia Terminal operated from 1861 to 1958. The terminal, completed in 1889 by the Erie Railroad, was at the end of the Long Dock which extended into the partially landfilled Harsimus Cove. The Jersey City Terminal was also used by the New York, Susquehanna and Western Railway, but was called by the name given to the seventeenth century New Netherland settlement of Pavonia. Ferry service began in the 1840s. The main Pavonia Ferry later ran to Chambers Street and 23rd Street. Pavonia's Erie trains were moved to Hoboken Terminal between 1956 and 1958, and the ferries and terminal abandoned. The terminal and yards have now been developed into the residential and commercial district of Pavonia-Newport.

Hoboken Terminal is the last of the Hudson River terminals still in use and is now operated by New Jersey Transit. Regular ferry service was started in 1834 by John Stevens. Train service began in 1863 by the Morris and Essex Railroad and was taken over by Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad, which built the terminal in 1908. The DL&W later consolidated with the Erie to create the Erie Lackawanna Railway which, after becoming part of Conrail, operated until the state takeover in the 1970s. The main routes of the Hoboken Ferry ran to Barclay Street, Christopher Street and 23rd Street; these ferries operated until 1967. Today New York Waterway ferries travel to the Battery Park City Ferry Terminal, Pier 11 at Wall Street and the West Midtown Ferry Terminal.

Weehawken Terminal operated from 1884 to 1959 as the terminus for New York Central Railroad's West Shore Railroad division as well as for the New York, Ontario and Western Railway. The extensive Weehawken Yards also handle freight for the Erie Railroad with the New Jersey Junction Railroad. The New York Central Railroad 69th Street Transfer Bridge is now a historic site. The main Weehawken Ferry travelled directly across the river to 42nd Street and for a time was part of route of the Lincoln Highway. Other ferries included those to 14th Street and Cortland Street. The original tunnel under Bergen Hill is now used by the Hudson Bergen Light Rail. Ferry service is now provided from Weehawken Port Imperial to West Midtown Ferry Terminal, BPC Ferry Terminal, and Wall Street.- The New York, Susquehanna and Western Railway terminus in Shadyside, Edgewater was opened in 1894 for the shipment of coal and other products. This led to extensive landfilling and industrial growth including plants of Hess Oil and Chemical, Lever Brothers, Alcoa, and the Ford Motor Company. Many workers from Manhattan used the ferry from 125th Street to reach their jobs. The factories of Edgewater have been demolished, the brownfields redeveloped for residential, retail, and recreational uses. The ferry now travels from Edgewater Landing to West Midtown Ferry Terminal.

Fixed crossings

| Crossing | Carries | Location | Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|

Downtown Hudson Tubes | PATH | Exchange Place and World Trade Center | |

Holland Tunnel | Jersey City and Lower Manhattan | 40°43′39″N 74°01′16″W / 40.72750°N 74.02111°W / 40.72750; -74.02111 | |

Uptown Hudson Tubes | PATH | Jersey City and Midtown Manhattan | |

North River Tunnels | Amtrak New Jersey Transit | Weehawken and Midtown Manhattan | 40°45′32″N 74°00′46″W / 40.75889°N 74.01278°W / 40.75889; -74.01278 |

| (part of New York Tunnel Extension between North Bergen and Long Island City) | |||

Lincoln Tunnel | Weehawken and Midtown Manhattan | 40°45′47″N 74°00′36″W / 40.76306°N 74.01000°W / 40.76306; -74.01000 | |

George Washington Bridge | Fort Lee and Upper Manhattan | 40°51′05″N 73°57′09″W / 40.85139°N 73.95250°W / 40.85139; -73.95250 | |

The last crossing to be built was the south tube of the Lincoln Tunnel in 1957, but in 1962, another deck was added to the George Washington Bridge.[42] Since 2003, various proposals have been made to add a new train line. This includes an extension of the nearly-completed 7 Subway Extension, the canceled Access to the Region's Core, and the proposed Gateway Project.

See also

- List of ferries across the Hudson River to New York City

- Timeline of Jersey City area railroads

- New York Harbor

- Geography of New York Harbor

- List of New Jersey rivers

- List of New York rivers

- List of bridges, tunnels, and cuts in Hudson County, New Jersey

References

^ The Random House Dictionary (2009) ("Part of the Hudson River between NE New Jersey and SE New York.")

^ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language,'Fourth Edition (2006) ("An estuary of the Hudson River between New Jersey and New York City flowing into Upper New York Bay.")

^ Webster's New World College Dictionary (2005) ("The lower course of the Hudson River, between New York City & NE N.J.")

^ The Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary (2009) Archived May 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine ("An estuary of Hudson River between SE New York & NE New Jersey" )

^ Joint Report With Comprehensive Plan and Recommendations New York, New Jersey Port and Harbor Development Commission (1926)

^ McCarten, John (July 4, 1959). "Harbor Display". The New Yorker. Retrieved January 27, 2011..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Steinhauer, Jennifer."F.Y.I",The New York Times, May 15, 1994. Accessed January 17, 2008. "The North River was the colonial name for the entire Hudson River, just as the Delaware was known as the South River. These names went out of use sometime early in the century, said Norman Brouwer, a historian at the South Street Seaport Museum."

^ North River Historic Ship Society Archived July 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

^ The Great North River Tugboat Race and Competition Archived December 1, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

^ "North River Sail & Power Squadron (NRSPS)". www.northriversquadron.org. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

^ "Lopez, Doerner, Malloy and friends brave the Hudson to raise autism awareness, SEA PADDLE NYC - SURFLINE.COM". www.surfline.com. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

^ Baxter, Raymond J.; Adams, Arthur G. (1999), Railroad Ferries of the Hudson: And Stories of a Deckhand, Fordham University Press, p. 5, ISBN 9780823219544

^ Glanz, James; Lipton, Eric (November 12, 2003). "City in the Sky: The Rise and Fall of the World Trade Center". Macmillan. Retrieved March 3, 2018 – via Google Books.

^ Pettengill, G. T. (March 2, 1908), "Hudson, Not North River" (PDF), The New York Times, retrieved January 25, 2011

^ Cox, Edwin M. (October 6, 1909), "Hudson or North River" (PDF), The New York Times, retrieved January 25, 2011

^ "Hudson and not North River" (PDF), The New York Times, September 26, 1909, retrieved January 25, 2011

^ "The North River in New Netherland". World Digital Library. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

^ Roberts, Sam. "Brooklyn Murders, Depression Love, a Glamorous Librarian", The New York Times, June 24, 2007. Accessed January 6, 2008. "You may even be directed to the sewage treatment plant in West Harlem, practically the last vestige of the name that, legend has it, the Dutch bestowed on the tidal estuary navigated by Henry Hudson to distinguish it from the South River, now known as the Delaware."

^ Dougherty, Steve. "MY MANHATTAN; Away From the Uproar, Before a Strong Wind", The New York Times, May 31, 2002. Accessed January 17, 2008. "'Because it's the river you sail to go north,' Captain Freitas explained. 'To sail east, to Long Island Sound, you would take the East River.'"

^ Portions of the Gallatin Report, 1808, Included in the Preliminary Report of the Inland Waterways Commission, 1908

^ "Chart 12335". www.charts.noaa.gov. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

^ GNIS Detail - Hudson River

^ "Pier 1". March 29, 1976. Retrieved March 3, 2018 – via www.newyorker.com.

^ Stewart, Barbara (June 1, 2000). "Hudson River Park On Restored Piers Approved By U.S". The New York Times. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

^ "Planning & Construction - Hudson River Park". Retrieved March 3, 2018.

^ "Pier 25 - Hudson River Park". Retrieved March 3, 2018.

^ "New looks at Pier 26's eco-friendly makeover, commencing this summer". Curbed NY. Retrieved 2018-04-30.

^ "Chelsea Waterside Play Area - Hudson River Park". Retrieved March 3, 2018.

^ "MARINE 1 F.D.N.Y." marine1fdny.com. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

^ "New York Architecture Images- Hell's Kitchen History". www.nyc-architecture.com. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

^ ab West, Melanie G. (November 17, 2014). "Hudson River Park Gets $100 Million Launch". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved November 17, 2014.

^ ab "Here's The Spectacular $165 Million Park Planned For The Hudson River". Gothamist. November 17, 2014. Archived from the original on November 20, 2014. Retrieved November 17, 2014.

^ ab "With Bold Park Plan, Mogul Hopes to Leave Mark on New York's West Side". The New York Times. November 17, 2014. Retrieved November 17, 2014.

^ Bagli, Charles V. (September 13, 2017). "Billionaire Diller's Plan for Elaborate Pier in the Hudson is Dead". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 19, 2017.

^ Bagli, Charles V. (October 25, 2017). "'Diller Island' Is Back From the Dead". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 31, 2017.

^ "Towed Vehicles - NYPD". www1.nyc.gov. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

^ "Directions". www.nywaterway.com. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

^ "Pier 84 Play Area - Hudson River Park". Retrieved March 3, 2018.

^ Fried, Joseph P. (August 13, 2009). "The City Hopes to Double the Size of Manhattan's No. 2 Convention Center, in the West 50s". New York Times. Retrieved January 30, 2009.

^ Open Pennsylvania Station To-night, The New York Times November 26, 1910 page 5

^ "GREAT RAILROADS AT WAR Fighting to Secure Lands on Jersey Shore" (PDF). New York Times. December 15, 1889. Retrieved November 16, 2010.

^ PANYNJ, "History Across the Hudson", The Star Ledger, archived from the original on July 14, 2011, retrieved March 15, 2011

Further reading

- A Guide to a Hudson River Park Walk from Battery Park to Riverside Park

- Wired New York - Hudson River Piers

- North River Historic Ship Society: Historic Vessels of New York Harbor

Coordinates: 40°47′12″N 73°59′31″W / 40.78667°N 73.99194°W / 40.78667; -73.99194

Comments

Post a Comment