Street organ

Organ-grinder in Vienna

A street organ played by an organ grinder is an automatic mechanical pneumatic organ designed to be mobile enough to play its music in the street. The two most commonly seen types are the smaller German and the larger Dutch street organ.

Contents

1 History

2 Organ grinders

3 Operation

4 Modern usage

5 Varieties

5.1 Dutch street organ

5.2 German street organ

6 See also

7 References

8 External links

History

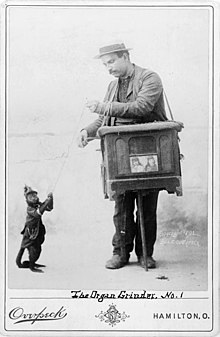

An organ grinder with a monkey, 1892.

The first descriptions of the street organ, at that time always a barrel organ owing to its use of a pinned cylinder (barrel) to operate levers and play notes, can be found in literature as early as the late 18th century.[1] Many were built by Italian organ builders who had settled in France and Germany, creating companies such as Frati, Gavioli, Gasparini and Fassano. These early organs had more pipes than the serinette, could play more than one tune,[1] and were considerably larger, in sizes up to 75 cm (29 in) long and 40 cm (16 in) deep.[2] Wooden bass pipes were placed underneath the organ and on the front were often mounted a set of pan-flutes or piccolo pipes, with decorative finishes.[3]

In many towns in Europe the barrel street organ was not just a solo performer, but used by a group of musicians as part of a story-telling street act, together with brightly coloured posters and sing-along sessions.[3] In New York City, the massive influx of Italian immigrants led to a situation where by 1880 nearly one in 20 Italian men in certain areas were organ grinders.[4]

The barrels used were heavy, held only a limited number of tunes, and could not easily be upgraded to play the latest hits, which greatly limited the musical and practical ability of these instruments.

In New York, where monkeys were commonly used by organ grinders, mayor Fiorello La Guardia banned the instruments from the streets in 1935, citing traffic congestion, the "begging" inherent in the profession, and organized crime's role in renting out the machines.[5][6] An unfortunate consequence was the destruction of hundreds of organs, the barrels of which contained a record of the popular music of the day. Before the invention of the cylinder record player, this was the only permanent recording of these tunes. The law that banned barrel organs in New York was repealed in 1975 but that mode of musical performance had become obsolete by then.

Many cities in the United Kingdom also had ordinances prohibiting organ grinders. The authorities often encouraged policemen to treat the grinders as beggars or public nuisances.

In the Netherlands the street organ was no more popular initially, but thanks to several organ hire companies who took particular pride in the condition, sound and repertoire of their instruments, the public there became more accepting of the orgelman (organ man) and as a result the tradition of playing an organ on the street entered Dutch culture where they remained a common sight until the beginning of the 21st century; they have all but vanished, since.

In Paris there were a limited number of permits for organ grinders, and entry in that reserved circle was based on a waiting list or seniority system.

According to Ord-Hume[7] the disappearance of organ grinders from European streets was in large part due to the early application of national and international copyright laws. At the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century European publishers of sheet music and the holders of copyrights to the most popular operatic tunes of the day often banded together in order to enforce collection of performance duties from any musician playing their property in any venue.

When faced with notaries and the hounding of other legal representatives of the music industry of the time, in addition to the other sources of hostility mentioned above organ grinders soon disappeared.

Organ grinders

An organ grinder in Mexico City

The organ grinder was a musical novelty street performer of the 19th century and the early part of the 20th century, and refers to the operator of a street or barrel organ.

Period literature often represents the grinder as a gentleman of ill repute or as an unfortunate representative of the lower classes.[8] Newspaper reporters would sometimes describe them cynically or jocularly as minor extortionists who were paid to keep silent, given the repetitious nature of the music. Later depictions would stress the romantic or picturesque aspects of the activity. Whereas some organ grinders were very likely itinerants or vagabonds, many, certainly in New York, were Italian immigrants who chose to be street performers in order to support their families.[4]

The stereotypical organ grinder was a man, bearing a medium-sized barrel organ held in front of him and supported by a hinged or removable wooden stick or leg that was strapped to the back of the organ. The strap around his neck would balance the organ, leaving one hand free to turn the crank and the other to steady the organ. A tin cup on top of the organ or in the hand of a companion, was used to solicit payments for his performance.

Moving away from the stereotype, in reality the size of the street organ varied from a tiny barrel organ with only 20 or fewer pipes, weighing only a few pounds, through medium-sized instruments containing forty or more pipes, mounted on a hand-pushed trolley, up to large ornately decorated book-operated organs, with hundreds of pipes weighing several hundred pounds.[3] The largest organs were usually mounted on a cart, and required a team of operators to move, particularly in the Netherlands when crossing the steep canal bridges of Amsterdam streets. The most elaborate organs would have mechanical figures or automata mounted on top of or in the front of the case, along with percussion instruments.

Operation

The grinder would crank the organ in any public place (either a business district or in a neighborhood), moving from place to place after collecting a few coins or in order to avoid being arrested for loitering or chased by people who do not appreciate hearing his single tune repeatedly. The grinder would often have as a companion a white-headed capuchin monkey, tethered to a string, to do tricks and attract attention,[4][9] as well as the important task of collecting money from passers-by.

In an article from 1929, George Orwell wrote of the organ-grinders of London: "To ask outright for money is a crime, yet it is perfectly legal to annoy one's fellow citizens by pretending to entertain them. Their dreadful music is the result of a purely mechanical gesture, and is only intended to keep them on the right side of the law. There are in London around a dozen firms specialising in the manufacture of piano organs, which they hire out for 15 shillings a week. The poor devil drags his instrument around from ten in the morning till eight or nine at night [–] the public only tolerates them grudgingly – and this is only possible in working-class districts, for in the richer districts the police will not allow begging at all, even when it is disguised. As a result, the beggars of London live mainly on the poor."[8]

Music lovers usually hated the organ grinders, since most grinders seemed to be tone-deaf and lacking any sense of rhythm.[citation needed] They apparently were not interested in keeping their instrument in tune or cranking at a rate suited to the music which was "programmed" in their barrel organ. This was most likely true of the organs that were rented for the day from "organ liveries". The organ grinder would pick up an organ in a small storefront shop and then walk or take the streetcar to his chosen neighborhood. After moving from block to block throughout the day, he would return the organ to the livery and pay a portion of the take to the owner.

Charles Dickens wrote to a friend that he could not write for more than half an hour without being disturbed by the most excruciating sounds imaginable, coming in from barrel organs on the street. Charles Babbage was a particularly virulent enemy of the organ grinders. He would chase them around town, complain to authorities about their noisy presence, and forever ask the police to arrest them.[10] The violinist Yehudi Menuhin, on the other hand, is quoted to have said: "we musicians must stick together" while handing an organ-grinder some change.[citation needed]

Modern usage

There are still persons today who own and sometimes operate a barrel organ on a street. They have very little in common with the calling of the organ grinder of yore. For instance, it is considered lucky for a couple in Denmark to have a barrel organ playing outside on the morning of their 25th wedding anniversary, thus creating a small niche for professional musicians or musicologists capable of tuning one of the few surviving barrel organs, and interested in maintaining an old tradition in their spare time.

A few organ grinders still remain, perhaps most famously Joe Bush in the United States.[5]

In addition to a few antique barrel organs, there are many more modern organs that have been built. These do not operate on pinned barrels anymore, but use perforated paper rolls (analogous to player pianos) or perforated cardboard book music (this method is mostly to be found in France,[11] the Netherlands or Belgium) and sometimes even electronic microchip- and/or MIDI-systems. Organ grinders are a common sight in Mexico City, and the related street organs are common in Germany and the Netherlands.

Some modern day organ grinders like to dress in period costumes, albeit not necessarily those of an organ-grinder. He would be found at an "organ rally" (such as the "MEMUSI" event in Vienna), where lots of enthusiasts would come together and entertain on the streets, but equally so at a wedding (usually performing the Lohengrin tune) or at any other event where he might be chosen over hiring an entire band or a deejay.

Larger organs are not usually turned by hand, but use an electric motor. Such larger instruments are called a fairground organ, band organ or orchestrion.

In the United Kingdom, many incorrectly use the term street organ to refer to a mechanically played, piano-like instrument also known as a barrel piano.

Varieties

Dutch street organ

The Dutch street organ Australia Fair, viewed from the front on a street corner in Sydney, Australia.

Street Organ showing full size (with people to show scale) at Floriade (Canberra) in 2013

Rear of Australia Fair. Note fanfold book playing through keyframe in centre and belt drive.

Dutch street organs (unlike the simple street organ) are large organs that play book music. They are equipped with multiple ranks of pipes and percussion. As originally built the organ was operated by the 'organ grinder' turning a large handle to operate both the bellows/reservoir and the card feed mechanism. Almost all examples in the Netherlands have now been converted to belt drive from a small battery powered motor or donkey engine, allowing the organ grinder to collect money.

Slightly smaller than the semi-trailer-sized fairground organ the Dutch street organ is nevertheless able to produce enough volume to be heard easily on a busy street corner. Modern Dutch street organs are frequently trailer mounted, and sized for towing behind a pickup or other light truck. Some have a small engine on the front of the chassis allowing them to be self-propelled.

Dutch street organs are on display at the Museum Speelklok (formerly 'Nationaal Museum van Speelklok tot Pierement') in Utrecht.

German street organ

German-style street organs are usually operated by a music roll or pinned barrel.

A street organ (locally called Werklmann) player with his paper roll-driven Berlin-style barrel organ in Vienna.

A street organ player in Warnemünde, Germany.

Play media

Play media

A Street barrel organ playing in Berlin Mitte - Nikolaiviertel (Video)

See also

Barrel organ: a mechanical organ operated by a pinned barrel rather than a Music Roll or Book music

Dance organ: an organ that plays in a dance hall, ball room or cafe

Fairground organ: an organ that plays on a fairground- Mechanical organ

References

^ ab Zeraschi, Helmut (1976). Drehorgeln. Berne and Stuttgart..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Jüttemann, Herbert (1993). Waldkircher Dreh- und Jahrmarktorgeln. Waldkircher Verlag.

^ abc de Waard, Romke (1967). From Music Boxes to Street Organs. The Vestal Press.

^ abc "The sudden demise of New York's organ grinders". Retrieved 5 January 2015.

^ ab "Joe Bush Organ Grinder". Retrieved 3 January 2015.

^ Roberts, Sam (8 February 2010), "Way Back Machine : If Not for Bias in Ariz., N.Y. Might Be Good for Organ Grinders", New York Times, retrieved 8 February 2010

^ Ord-Hume, Arthur WJG (1978). Barrel Organ: The Story of the Mechanical Organ and Its Repair. George Allen and Unwin.

^ ab George Orwell, A Kind of Compulsion, 1903–36, p.134, from 'Beggars in London', first published in Le Progrès Civique, 12 January 1929

^ "Capuchin Monkey". Retrieved 3 January 2015.

^ Babbage, Charles (1864) Passages from the Life of a Philosopher, London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, & Green, Chapter 26, page 342.

ISBN 1-85196-040-6

^ where the street organ is known as orgue de Barbarie

- Reblitz, Arthur A. The Golden Age of Automatic Musical Instruments. Woodsville, New Hampshire: Mechanical Music Press, 2001.

- Reblitz, Arthur A., Q. David Bowers. Treasures of Mechanical Music. New York: The Vestal Press, 1981.

- Smithsonian Institution. History of Music Machines. New York: Drake Publishers, 1975.

Mechanical Music Digest (since 1995)- Quotation #2796 by Winston Churchill, from Laura Moncur's Motivational Quotations

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Street organs. |

Dutch street organs, a brief summary

Video documentary: Street organ in Mexico (2 min) (in English) (in Spanish)

- A picture of a 1930s American organ grinder

Comments

Post a Comment