Béla IV of Hungary

| Béla IV | |

|---|---|

| |

King of Hungary and Croatia | |

| Reign | 21 September 1235 – 3 May 1270 |

| Coronation | 1214 14 October 1235 |

| Predecessor | Andrew II |

| Successor | Stephen V |

| Duke of Styria | |

| Reign | 1254–1258 |

| Predecessor | Ottokar V |

| Successor | Stephen |

| Born | 1206 |

| Died | 3 May 1270(1270-05-03) (aged 63–64) Rabbits' Island (now Margaret Island, Budapest) |

| Burial | Minorites' Church, Esztergom |

| Spouse | Maria Laskarina |

| Issue more... | Kunigunda Anna Elizabeth Constance Yolanda Stephen V of Hungary Margaret Béla |

| Dynasty | Árpád dynasty |

| Father | Andrew II of Hungary |

| Mother | Gertrude of Merania |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

Béla IV (1206 – 3 May 1270), also known as Béla the Great,[citation needed] was King of Hungary and Croatia between 1235 and 1270, and Duke of Styria from 1254 to 1258. Being the oldest son of King Andrew II, he was crowned upon the initiative of a group of influential noblemen in his father's lifetime in 1214. His father, who strongly opposed Béla's coronation, refused to give him a province to rule until 1220. In this year, Béla was appointed Duke of Slavonia, also with jurisdiction in Croatia and Dalmatia. Around the same time, Béla married Maria, a daughter of Theodore I Laskaris, Emperor of Nicaea. From 1226, he governed Transylvania with the title Duke. He supported Christian missions among the pagan Cumans who dwelled in the plains to the east of his province. Some Cuman chieftains acknowledged his suzerainty and he adopted the title of King of Cumania in 1233. King Andrew died on 21 September 1235 and Béla succeeded him. He attempted to restore royal authority, which had diminished under his father. For this purpose, he revised his predecessors' land grants and reclaimed former royal estates, causing discontent among the noblemen and the prelates.

The Mongols invaded Hungary and annihilated Béla's army in the Battle of Mohi on 11 April 1241. He escaped from the battlefield, but a Mongol detachment chased him from town to town as far as Trogir on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. Although he survived the invasion, the Mongols devastated the country before their unexpected withdrawal in March 1242. Béla introduced radical reforms in order to prepare his kingdom for a second Mongol invasion. He allowed the barons and the prelates to erect stone fortresses and to set up their private armed forces. He promoted the development of fortified towns. During his reign, thousands of colonists arrived from the Holy Roman Empire, Poland and other neighboring regions to settle in the depopulated lands. Béla's efforts to rebuild his devastated country won him the epithet of "second founder of the state" (Hungarian: második honalapító).

He set up a defensive alliance against the Mongols, which included Daniil Romanovich, Prince of Halych, Boleslaw the Chaste, Duke of Cracow and other Ruthenian and Polish princes. His allies supported him in occupying the Duchy of Styria in 1254, but it was lost to King Ottokar II of Bohemia six years later. During Béla's reign, a wide buffer zone—which included Bosnia, Barancs (Braničevo, Serbia) and other newly conquered regions—was established along the southern frontier of Hungary in the 1250s.

Béla's relationship with his oldest son and heir, Stephen, became tense in the early 1260s, because the elderly king favored his daughter Anna and his youngest child, Béla, Duke of Slavonia. He was forced to cede the territories of the Kingdom of Hungary east of the river Danube to Stephen, which caused a civil war lasting until 1266. Nevertheless, Béla's family was famed for his piety: he died as a Franciscan tertiary, and the veneration of his three saintly daughters—Kunigunda, Yolanda, and Margaret—was confirmed by the Holy See.

Contents

1 Childhood (1206–20)

2 Rex iunior

2.1 Duke of Slavonia (1220–26)

2.2 Duke of Transylvania (1226–35)

3 His reign

3.1 Before the Mongol invasion (1235–41)

3.2 Mongol invasion of Hungary (1241–42)

3.3 "Second Founder of the State" (1242–61)

3.4 Civil war (1261–66)

3.5 Last years (1266–70)

4 Family

5 Legacy

6 References

7 Sources

7.1 Primary sources

7.2 Secondary sources

8 External links

Childhood (1206–20)

Béla's parents—Gertrude of Merania and Andrew II of Hungary—depicted in the 13th-century Landgrafenpsalter from the Landgraviate of Thuringia

Béla was the oldest son of King Andrew II of Hungary by his first wife, Gertrude of Merania.[1][2] He was born in the second half of 1206.[1][3] Upon King Andrew's initiative, Pope Innocent III had already appealed to the Hungarian prelates and barons on 7 June to swear an oath of loyalty to the King's future son.[3][4]

Queen Gertrude showed blatant favoritism towards her German relatives and courtiers, causing widespread discontent among the native lords.[5][6] Taking advantage of her husband's campaign in the distant Principality of Halych, a group of aggrieved noblemen seized and murdered her in the forests of the Pilis Hills on 28 September 1213.[5][7] King Andrew only punished one of the conspirators, a certain Count Peter, after his return from Halych.[8] Although Béla was a child when his mother was assassinated, he never forgot her and declared his deep respect for her in many of his royal charters.[3] In his correspondence with his sister, the noted Franciscan saint, Elizabeth of Hungary, he was often counseled to restrain his anger at the nobles for the death of their mother.[citation needed]

Andrew II betrothed Béla to an unnamed daughter of Tzar Boril of Bulgaria in 1213 or 1214, but their engagement was broken.[9][10] In 1214, the King requested the Pope to excommunicate some unnamed lords who were planning to crown Béla king.[3][11] Even so, the eight-year-old Béla was crowned in the same year, but his father did not grant him a province to rule.[12] Furthermore, when leaving for a Crusade to the Holy Land in August 1217, King Andrew appointed John, Archbishop of Esztergom, to represent him during his absence.[13][14] During this period, Béla stayed with his maternal uncle Berthold of Merania in Steyr in the Holy Roman Empire.[13] Andrew II returned from the Holy Land in late 1218.[15] He had arranged the engagement of Béla and Maria, a daughter of Theodore I Laskaris, Emperor of Nicaea.[13] She accompanied King Andrew to Hungary and Béla married her in 1220.[1]

Rex iunior

Duke of Slavonia (1220–26)

Klis Fortress (seen from its west point, toward east); Béla captured it from Domald of Sidraga, a rebellious Dalmatian nobleman in 1223

The senior king ceded the lands between the Adriatic Sea and the Dráva River—Croatia, Dalmatia and Slavonia—to Béla in 1220.[12][16] A letter of 1222 of Pope Honorius III reveals that "some wicked men" had forced Andrew II to share his realms with his heir.[17] Béla initially styled himself as "King Andrew's son and King" in his charters; from 1222 he used the title "by the Grace of God, King, son of the King of Hungary, and Duke of all Slavonia".[13]

Béla separated from his wife in the first half of 1222 upon his father's demand.[18][17] However, Pope Honorius refused to declare the marriage illegal.[19] Béla accepted the Pope's decision and took refuge in Austria from his father's anger.[20] He returned, together with his wife, only after the prelates had in the first half of 1223 persuaded his father to forgive him.[19] Having returned to his Duchy of Slavonia, Béla launched a campaign against Domald of Sidraga, a rebellious Dalmatian nobleman, and captured Domald's fortress at Klis.[19][20] Domald's domains were confiscated and distributed among his rivals, the Šubići, who had supported Béla during the siege.[21][22]

Duke of Transylvania (1226–35)

King Andrew transferred Béla from Slavonia to Transylvania in 1226.[23] In Slavonia, he was succeeded by his brother, Coloman.[24] As Duke of Transylvania, Béla adopted an expansionist policy aimed at the territories over the Carpathian Mountains.[25][26] He supported the Dominicans' proselytizing activities among the Cumans, who dominated these lands.[26][27] In 1227 he crossed the mountains and met Boricius, a Cuman chieftain, who had decided to convert to Christianity.[28] At their meeting, Boricius and his subjects were baptized and acknowledged Béla's suzerainty.[26] Within a year, the Roman Catholic Diocese of Cumania was established in their lands.[29]

Béla had long opposed his father's "useless and superfluous perpetual grants", because the distribution of royal estates destroyed the traditional basis of royal authority.[30] He started reclaiming King Andrew's land grants throughout the country in 1228.[31] The Pope supported Béla's efforts, but the King often hindered the execution of his son's orders.[31][32] Béla also confiscated the estates of two noblemen, brothers Simon and Michael Kacsics, who had plotted against his mother.[32][31]

Ruins of the fortress of Halych

Béla's youngest brother, Andrew, Prince of Halych, was expelled from his principality in the spring of 1229.[33] Béla decided to help him to regain his throne, proudly boasting that the town of Halych "would not remain on the face of the earth, for there was no one to deliver it from his hands",[34] according to the Galician–Volhynian Chronicle.[32] He crossed the Carpathian Mountains and laid siege to Halych together with his Cuman allies in 1229 or 1230.[32][28] However, he could not seize the town and withdrew his troops.[32][28] The Galician–Volhynian Chronicle writes that many Hungarian soldiers "died of many afflictions"[35] on their way home.[32]

Béla invaded Bulgaria and besieged Vidin in 1228 or 1232, but he could not capture the fortress.[33][36][37] Around the same time, he set up a new border province, the Banate of Szörény (Severin, Romania), in the lands between the Carpathians and the Lower Danube.[37][27][38] In a token of his suzerainty in the lands east of the Carpathians, Béla adopted the title "King of Cumania" in 1233.[27][26] Béla sponsored the mission of Friar Julian and three other Dominican friars who decided to visit the descendants of the Hungarians who had centuries earlier remained in Magna Hungaria, the Hungarians' legendary homeland.[39][40][41]

His reign

Before the Mongol invasion (1235–41)

Béla is crowned king (from the Illuminated Chronicle)

King Andrew died on 21 September 1235.[42] Béla, who succeeded his father without opposition, was crowned king by Robert, Archbishop of Esztergom in Székesfehérvár on 14 October.[42][43] He dismissed and punished many of his father's closest advisors.[31] For instance, he had Palatine Denis blinded and Julius Kán imprisoned.[31][40] The former was accused of having, in King Andrew's life, an adulterous liaison with Queen Beatrix, the King's young widow.[44] Béla ordered her imprisonment, but she managed to escape to the Holy Roman Empire, where she gave birth to a posthumous son, Stephen.[45] Béla and his brother Coloman considered her son a bastard.[46][47]

Béla declared that his principal purpose was "the restitution of royal rights" and "the restoration of the situation which existed in the country" in the reign of his grandfather, Béla III.[48] According to the contemporaneous Roger of Torre Maggiore, he even "had the chairs of the barons burned"[49] in order to prevent them from sitting in his presence during the meetings of the royal council.[31] Béla set up special commissions which revised all royal charters of land grants made after 1196.[48] The annulment of former donations alienated many of his subjects from the King.[31]Pope Gregory IX protested strongly at the withdrawal of royal grants made to the Cistercians and the military orders.[41][46] In exchange for Béla's renouncing of the taking back of royal estates in 1239, the Pope authorized him to employ local Jews and Muslims in financial administration, which had for decades been opposed by the Holy See.[41][50]

After returning from Magna Hungaria in 1236, Friar Julian informed Béla of the Mongols, who had by that time reached the Volga River and were planning to invade Europe.[48] The Mongols invaded Desht-i Qipchaq—the westernmost regions of the Eurasian Steppes—and routed the Cumans.[51] Fleeing the Mongols, at least 40,000 Cumans approached the eastern borders of the Kingdom of Hungary and demanded admission in 1239.[52][53] Béla only agreed to give them shelter after their leader, Köten, promised to convert together with his people to Christianity, and to fight against the Mongols.[52][54][55] However, the settlement of masses of nomadic Cumans in the plains along the Tisza River gave rise to many conflicts between them and the local villagers.[52] Béla, who needed the Cumans' military support, rarely punished them for their robberies, rapes and other misdeeds.[52][56] His Hungarian subjects thought that he was biased in the Cumans' favor, thus "enmity emerged between the people and the king",[57] according to Roger of Torre Maggiore.[58]

Béla supported the development of towns.[42] For instance, he confirmed the liberties of the citizens of Székesfehérvár and granted privileges to Hungarian and German settlers in Bars (Starý Tekov, Slovakia) in 1237.[46]Zadar, a town in Dalmatia which had been lost to Venice in 1202, acknowledged Béla's suzerainty in 1240.[59]

Mongol invasion of Hungary (1241–42)

The Mongols gathered in the lands bordering Hungary and Poland under the command of Batu Khan in December 1240.[51][59] They demanded Béla's submission to their Great Khan Ögödei, but Béla refused to yield and had the mountain passes fortified.[54][52] The Mongols broke through the barricades erected in the Verecke Pass (Veretsky Pass, Ukraine) on 12 March 1241.[54][59]

Duke Frederick II of Austria, who arrived to assist Béla against the invaders, defeated a small Mongol troop near Pest.[52] He seized prisoners, including Cumans from the Eurasian Steppes who had been forced to join the Mongols.[52] When the citizens of Pest realized the presence of Cumans in the invading army, mass hysteria emerged.[60] The townsfolk accused Köten and their Cumans of cooperating with the enemy.[52] A riot broke out and the mob massacred Köten's retinue.[61] Köten was either slaughtered or committed suicide.[52] On hearing about Köten's fate, his Cumans decided to leave Hungary and destroyed many villages on their way towards the Balkan Peninsula.[62][63]

Mongols pursuing Béla after his catastrophic defeat in the Battle of Mohi on 11 April 1241 (from the Illuminated Chronicle)

With the Cumans' departure Béla lost his most valuable allies.[60] He could muster an army of less than 60,000 against the invaders.[64] The royal army was ill-prepared and its commanders—the barons alienated by Béla's policy—"would have liked the king to be defeated so that they would then be dearer to him",[65] according to Roger of Torre Maggiore's account.[60] The Hungarian army was virtually annihilated in the Battle of Mohi on the Sajó River on 11 April 1241.[54][66][67] A great number of Hungarian lords, prelates and noblemen were killed, and Béla himself narrowly escaped from the battlefield.[54] He fled through Nyitra to Pressburg (Nitra and Bratislava in Slovakia).[68] The triumphant Mongols occupied and ravaged most lands to the east of the Danube River by the end of June.[52][68]

Upon Duke Frederick II of Austria's invitation, Béla went to Hainburg an der Donau.[68] However, instead of helping Béla, the Duke forced him to cede three counties (most probably Locsmánd, Pozsony, and Sopron).[68][62] From Hainburg, Béla fled to Zagreb and sent letters to Pope Gregory IX, Emperor Frederick II, King Louis IX of France and other Western European monarchs, urging them to send reinforcements to Hungary.[68] In the hope of military assistance, he even accepted Emperor Frederick II's suzerainty in June.[68] The Pope declared a Crusade against the Mongols, but no reinforcements arrived.[68][69]

The Mongols crossed the frozen Danube early in 1242.[62] A Mongol detachment under the command of Kadan, a son of Great Khan Ögödei, chased Béla from town to town in Dalmatia.[70][71] Béla took refugee in the well-fortified Trogir.[70] Before Kadan laid siege to the town in March, news arrived of the Great Khan's death.[62][72] Batu Khan wanted to attend at the election of Ögödei's successor with sufficient troops and ordered the withdrawal of all Mongol forces.[73][74] Béla, who was grateful to Trogir, granted it lands near Split, causing a lasting conflict between the two Dalmatian towns.[75]

"Second Founder of the State" (1242–61)

Upon his return to Hungary in May 1242, Béla found a country in ruins.[69][74] Devastation was especially heavy in the plains east of the Danube where at least half of the villages were depopulated.[76][77] The Mongols had destroyed most traditional centers of administration, which were defended by earth-and-timber walls.[78] Only well-fortified places, such as Esztergom, Székesfehérvár and the Pannonhalma Archabbey, had successfully resisted siege.[77][78] A severe famine followed in 1242 and 1243.[79][80][81]

Ruins of the Sáros Castle (Šarišský hrad in Slovakia), a royal fortress built during the reign of Béla

Preparation for a new Mongol invasion was the central concern of Béla's policy.[76] In a letter of 1247 to Pope Innocent IV, Béla announced his plan to strengthen the Danube—the "river of confrontations"—with new forts.[82][83] He abandoned the ancient royal prerogative to build and own castles, promoting the erection of nearly 100 new fortresses by the end of his reign.[74][76] These fortresses included a new castle Béla had built at Nagysáros (Veľký Šariš, Slovakia), and another castle Béla and his wife had built at Visegrád.[76]

Béla attempted to increase the number of the soldiers and to improve their equipment.[76] He made land grants in the forested regions and obliged the new landowners to equip heavily armoured cavalrymen to serve in the royal army.[84] For instance, the so-called ten-lanced nobles of Szepes (Spiš, Slovakia) received their privileges from Béla in 1243.[85][86] He even allowed the barons and prelates to employ armed noblemen, who had previously been directly subordinated to the sovereign, in their private retinue.[87] Béla granted the Banate of Szörény to the Knights Hospitaller on 2 June 1247, but the Knights abandoned the region by 1260.[81][88]

Seal of Béla's daughter-in-law, Elizabeth the Cuman

To replace the loss of at least 15 percent of the population, who perished during the Mongol invasion and the ensuing famine, Béla promoted colonization.[79][80] He granted special liberties to the colonists, including personal freedom and favorable tax treatment.[89] Germans, Moravians, Poles, Ruthenians and other "guests" arrived from neighboring countries and were settled in depopulated or sparsely populated regions.[90] He also persuaded the Cumans, who had in 1241 left Hungary, to return and settle in the plains along the River Tisza.[86][91] He even arranged the engagement of his firstborn son, Stephen, who was crowned king-junior in or before 1246, to Elisabeth, a daughter of a Cuman chieftain.[91][92]

Béla granted the privileges of Székesfehérvár to more than 20 settlements, promoting their development into self-governing towns.[93] The liberties of the mining towns in Upper Hungary were also spelled out in Béla's reign.[94] For defensive purposes, he moved the citizens of Pest to a hill on the opposite side of the Danube in 1248.[95] Within two decades their new fortified town, Buda, became the most important center of commerce in Hungary.[96][93] Béla also granted privileges to Gradec, the fortified center of Zagreb, in 1242 and confirmed them in 1266.[97][98]

Béla adopted an active foreign policy soon after the withdrawal of the Mongols.[99][100] In the second half of 1242 he invaded Austria and forced Duke Frederick II to surrender the three counties ceded to him during the Mongol invasion.[72] On the other hand, Venice occupied Zadar in the summer of 1243.[72] Béla renounced Zadar on 30 June 1244, but Venice acknowledged his claim to one third of the customs revenues of the Dalmatian town.[72]

Béla set up a defensive alliance against the Mongols.[101] He married three of his daughters to princes whose countries were also threatened by the Mongols.[101]Rostislav Mikhailovich, a pretender to the Principality of Halych, was the first to marry, in 1243, one of Béla's daughters, Anna.[72][102] Béla supported his son-in-law to invade Halych in 1245, but Rostislav's opponent, Daniil Romanovich repulsed their attack.[103]

Tomb of Frederick the Quarrelsome, Duke of Austria in the Heiligenkreuz Abbey—he died fighting against the Hungarians in the Battle of the Leitha River on 15 June 1246

On 21 August 1245 Pope Innocent IV freed Béla of the oath of fidelity he had taken to Emperor Frederick during the Mongol invasion.[103] In the following year Duke Frederick II of Austria invaded Hungary.[88] He routed Béla's army in the Battle of the Leitha River on 15 June 1246, but perished in the battlefield.[88][104] His childless death gave rise to a series of conflicts,[100] because both his niece, Gertrude, and his sister, Margaret, made a claim to Austria and Styria.[citation needed] Béla decided to intervene in the conflict only after the danger of a second Mongol invasion had diminished by the end of the 1240s.[105] In retaliation of a former Austrian incursion into Hungary, Béla made a plundering raid into Austria and Styria in the summer of 1250.[106][107] In this year he met and concluded a peace treaty with Daniil Romanovich, Prince of Halych in Zólyom (Zvolen, Slovakia).[106] With Béla's mediation, a son of his new ally Roman married Gertrude of Austria.[108]

Béla and Daniil Romanovich united their troops and invaded Austria and Moravia in June 1252.[108][107] After their withdrawal, Ottokar, Margrave of Moravia—who had married Margaret of Austria—invaded and occupied Austria and Styria.[107] In the summer of 1253, Béla launched a campaign against Moravia and laid siege to Olomouc.[109] Daniil Romanovich, Boleslaw the Chaste of Cracow, and Wladislaw of Opole intervened on Béla's behalf, but he lifted the siege by the end of June.[110] Pope Innocent IV mediated a peace treaty, which was signed in Pressburg (Bratislava, Slovakia) on 1 May 1254.[110] In accordance with the treaty, Ottokar, who had in the meantime become King of Bohemia, ceded Styria to Béla.[110][111]

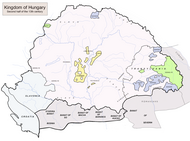

Kingdom of Hungary in the second half of the 13th century

Béla appointed his son-in-law, Rostislav Mikhailovich Ban of Macsó (Mačva, Serbia) in 1254.[110][112] Rostislav's task was the creation of a buffer zone along the southern borders.[113] He occupied Bosnia already in the year of his appointment and forced Tzar Michael Asen I of Bulgaria to cede Belgrade and Barancs (Braničevo, Serbia) in 1255.[112][114] Béla adopted the title of King of Bulgaria, but he only used it occasionally in the subsequent years.[114]

The Styrian noblemen rose up in rebellion against Béla's governor Stephen Gutkeled and routed him in early 1258.[115] Béla invaded Styria, restored his suzerainty and appointed his oldest son, Stephen, Duke of Styria.[115][116] In 1259, Batu Khan's successor, Berke, proposed an alliance by offering to marry one of his daughters to a son of Béla, but he refused the Khan's offer.[113][114]

Discontented with the rule of Béla's son, the Styrian lords sought assistance from Ottokar of Bohemia.[116] Béla and his allies—Daniil Romanovich, Boleslaw the Chaste, and Leszek the Black of Sieradz—invaded Moravia, but Ottokar vanquished them in the Battle of Kressenbrunn on 12 June 1260.[104][117][118] The defeat forced Béla to renounce Styria in favor of the King of Bohemia in the Peace of Vienna, which was signed on 31 March 1261.[104][119] On the other hand, Ottokar divorced his elderly wife, Margarete of Austria, and married Béla's granddaughter—the daughter of Rostislav Mikhailovich by Anna—Kunigunda.[104][119]

Béla had originally planned to give his youngest daughter, Margaret, in marriage to King Ottokar.[120] However, Margaret, who had been living in the Monastery of the Blessed Virgin on Rabbits' Island, refused to yield.[121][122] With the assistance of her Dominican confessor, she took her final religious vows which prevented her marriage.[120] Infuriated by this act, the King, who had up to that time supported the Dominicans, favored the Franciscans in the subsequent years.[120][121] He even became a Franciscan tertiary, according to the Greater Legend of his saintly sister, Elisabeth.[123]

Civil war (1261–66)

Ruins of the Dominican Monastery of the Blessed Virgin on Rabbits' Island (Margaret Island, Budapest) where the peace treaty ending the civil war between Béla and his son, Stephen was signed on 23 March 1266

Béla and his son, Stephen jointly invaded Bulgaria in 1261.[119][124][125] They forced Tzar Constantine Tikh of Bulgaria to abandon the region of Vidin.[125] Béla returned to Hungary before the end of the campaign, which was continued by his son.[126]

Béla's favoritism towards his younger son, Béla (whom he appointed Duke of Slavonia) and daughter, Anna irritated Stephen.[127][128] The latter suspected that his father was planning to disinherit him.[129] Stephen often mentioned in his charters that he had "suffered severe persecution" by his "parents without deserving it" when referring to the roots of his conflict with his father.[129] Although some clashes took place in the autumn, a lasting civil war was avoided through the mediation of the Archbishops Philip of Esztergom and Smaragd of Kalocsa who persuaded Béla and his son to make a compromise.[130][131] According to the Peace of Pressburg, the two divided the country along the Danube: the lands to the west of the river remained under the direct rule of Béla, and the government of the eastern territories was taken over by Stephen, the king-junior.[130]

The relationship between father and son remained tense.[127] Stephen seized his mother's and sister's estates which were situated in his realm to the east of the Danube.[132] Béla's army under Anna's command crossed the Danube in the summer of 1264.[133][127] She occupied Sárospatak and captured Stephen's wife and children.[130] A detachment of the royal army, under the command of Béla's Judge royal Lawrence forced Stephen to retreat as far as the fortress at Feketehalom (Codlea, Romania) in the easternmost corner of Transylvania.[130][127] The king-junior's partisans relieved the castle and he started a counter-attack in the autumn.[130][127] In the decisive Battle of Isaszeg, he routed his father's army in March 1265.[127]

It was again the two archbishops who conducted the negotiations between Béla and his son.[130] Their agreement was signed in the Dominican Monastery of the Blessed Virgin on Rabbits' Island (Margaret Island, Budapest) on 23 March 1266.[127][130] The new treaty confirmed the division of the country along the Danube and regulated many aspects of the co-existence of Béla's regnum and Stephen's regimen, including the collection of taxes and the commoners' right to free movement.[127][130]

Last years (1266–70)

Béla's royal seal

The "nobles of all Hungary, who are called servientes regis"[134] from both the senior and the junior king's domains assembled in Esztergom in 1267.[135] Upon their request, Béla and Stephen jointly confirmed their privileges, which had first been spelled out in the Golden Bull of 1222, before 7 September.[135][136] Shortly after the meeting, Béla assigned four noblemen from each county with the task of revising property rights in Transdanubia.[135]

King Stephen Uroš I of Serbia invaded the Banate of Macsó, a region under the rule of Béla's widowed daughter, Anna.[137][138] A royal army soon routed the invaders and captured Stephen Uroš.[137][139] The Serbian monarch was forced to pay ransom before being released.[137]

Béla's favorite son, also named Béla, died in the summer of 1269.[94] On 18 January 1270 the King's youngest daughter, the saintly Margaret, also died.[94] King Béla too soon fell terminally ill.[128] On his deathbed, he asked his grandson-in-law King Ottokar II of Bohemia to assist his wife, daughter and partisans in case they were forced to leave Hungary by his son.[128] Béla died on Rabbits' Island on 3 May 1270.[136][139] Dying at 63, he exceeded in age most members of the House of Árpád.[140] He was buried in the church of the Franciscans in Esztergom, but Archbishop Philip of Esztergom had his corpse transferred to the Esztergom Cathedral.[141] The Minorites only succeeded in regaining Béla's remains after a long lawsuit.[142]

Family

.mw-parser-output table.ahnentafel{border-collapse:separate;border-spacing:0;line-height:130%}.mw-parser-output .ahnentafel tr{text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .ahnentafel-t{border-top:#000 solid 1px;border-left:#000 solid 1px}.mw-parser-output .ahnentafel-b{border-bottom:#000 solid 1px;border-left:#000 solid 1px}

| Ancestors of Béla IV of Hungary[143][144][145] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The statute of Béla's youngest daughter, Margaret, who died as a Dominican nun and was canonized in 1943, on the Minorites' Church in Saint-Pol-de-Léon in France

Béla's wife, Maria Laskarina was born in 1207 or 1208, according to historian Gyula Kristó.[146] She died in July or August 1270.[142] Their first child, Kunigunda, was born in 1224, four years after her parents' marriage.[146][147] She married to Boleslaw the Chaste, Duke of Cracow in 1246.[148]

A second daughter, Margaret followed Kunigunda in about 1225; she died unmarried before 1242.[147][149] The third daughter of Béla, Anna was born around 1226.[147][149] She and her husband, Rostislav Mikhailovich were especially favored by Béla.[147][150] Her great-grandson, Wenceslaus—a grandson of her daughter, Kunigunda by King Ottokar II of Bohemia—was King of Hungary from 1301 to 1305.[151]

Béla's fourth child, Catherina died unmarried before 1242.[151] Next, Elisabeth was born; she was given in marriage to Henry XIII, Duke of Bavaria in about 1245.[147] Her son, Otto was crowned King of Hungary in 1305, but was forced to leave the country by the end of 1307.[152] Elisabeth's sister, Constance married, around 1251, Lev Danylovich, second son of Prince Daniil Romanovich of Halych.[153][72] Béla's seventh daughter, Yolanda became the wife of Bolesław the Pious, Duke of Greater Poland.[147]

Béla's first son, Stephen was born in 1239.[154] He succeeded his father.[155] Béla's youngest daughter, Margaret was born during the Mongol invasion in 1242.[122] Dedicated to God by her parents at birth, she spent her life in humility in the Monastery of the Blessed Virgin on Rabbits' Island and died as a Dominican nun.[122] The King's youngest (namesake) son, Béla was born between around 1243 and 1250.[156]

The Greater Legend of Saint Elisabeth of Hungary (Béla's sister) described Béla's family as a company of saints.[157] It wrote that the "blessed royal family of the Hungarians is adorned with resplendent pearls that irradiate all the earth".[157] In fact, the Holy See sanctioned the veneration of three daughters of Béla and his wife: Kunigunda was beatified in 1690,[158] Yolanda in 1827;[159] and Margaret was canonized in 1943.[160] A fourth daughter, Constance also became subject to a local cult in Lemberg (Lviv, Ukraine), according to the Legend of her sister, Kunigunda.[123]

The following family tree presents Béla's offspring, and some of his relatives mentioned in the article.[161]

Andrew II of Hungary ∞(1)Gertrude of Merania ∞(2)Yolanda de Courtenay ∞(3)Beatrice d'Este | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (1) Béla IV ∞Maria Laskarina | (1) St Elisabeth | (1) Coloman, Duke of Slavonia | (1) Andrew, Prince of Halych | (1) and (2) two daughters | (3) Stephen the Posthumous | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

St Kunigunda ∞Boleslav V of Cracow | Margaret | Anna ∞Rostislav Mikhailovich | Catherina | Elisabeth ∞Henry XIII of Bavaria | Constance ∞Lev Danylovich | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Blessed Yolanda ∞Boleslav of Greater Poland | Stephen V of Hungary ∞Elisabeth the Cuman | Saint Margaret | Béla, Duke of Slavonia ∞Kunigunde of Brandenburg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Legacy

Béla's statue (Heroes' Square, Budapest)

Bryan Cartledge writes that Béla "reorganised the structure of government, re-established the rule of law, repopulated a devastated countryside, encouraged the growth of towns, created the new royal town of Buda and revived the commercial life of the country" during his over three-decade-long reign.[91] Béla's posthumous epithet—the "second founder of the state" (Hungarian: második honalapító)—shows that posterity attributed to him Hungary's survival of the Mongol invasion.[162] On the other hand, the Illuminated Chronicle notes that Béla "was a man of peace, but in the conduct of armies and battles the least fortunate"[163] when narrating Béla's defeat in the Battle of Kressenbrunn.[117] The same chronicle preserved the next epigram which was written on his tomb:[117]

.mw-parser-output .quotebox{background-color:#F9F9F9;border:1px solid #aaa;box-sizing:border-box;padding:10px;font-size:88%}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft{margin:0.5em 1.4em 0.8em 0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright{margin:0.5em 0 0.8em 1.4em}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.centered{margin:0.5em auto 0.8em auto}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft p,.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright p{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-title{background-color:#F9F9F9;text-align:center;font-size:larger;font-weight:bold}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:before{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" “ ";vertical-align:-45%;line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:after{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" ” ";line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .left-aligned{text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .right-aligned{text-align:right}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .center-aligned{text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .quotebox cite{display:block;font-style:normal}@media screen and (max-width:360px){.mw-parser-output .quotebox{min-width:100%;margin:0 0 0.8em!important;float:none!important}}

King, duke, and queen, whom threefold joys attend.

So long as might thy power, King Béla, last,

fraud hid itself, peace flourished, virtue reigned."

Illuminated Chronicle[164]

References

^ abc Almási 1994, p. 92.

^ Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 247, Appendix 4.

^ abcd Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 247.

^ Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 127.

^ ab Bartl et al. 2002, p. 30.

^ Makkai 1994a, p. 24.

^ Molnár 2001, p. 33.

^ Engel 2001, p. 91.

^ Fine 1994, p. 102.

^ Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 131.

^ Engel 2001, pp. 93–94.

^ ab Engel 2001, p. 94.

^ abcd Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 248.

^ Kontler 1999, p. 76.

^ Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 133.

^ Kristó & Makk 1996, pp. 248–249.

^ ab Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 249.

^ Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 136.

^ abc Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 137.

^ ab Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 250.

^ Fine 1994, p. 150.

^ Magaš 2007, p. 66.

^ Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 251.

^ Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 138.

^ Curta 2006, pp. 405–406.

^ abcd Engel 2001, p. 95.

^ abc Makkai 1994b, p. 193.

^ abc Curta 2006, p. 406.

^ Curta 2006, p. 407.

^ Engel 2001, pp. 91–93, 98.

^ abcdefg Engel 2001, p. 98.

^ abcdef Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 252.

^ ab Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 139.

^ The Galician-Volynian Chronicle (year 1230), p. 37.

^ The Galician-Volynian Chronicle (year 1230), p. 38.

^ Curta 2006, p. 387.

^ ab Fine 1994, p. 129.

^ Curta 2006, p. 388.

^ Kontler 1999, p. 77.

^ ab Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 144.

^ abc Cartledge 2011, p. 28.

^ abc Bartl et al. 2002, p. 31.

^ Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 254.

^ Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 255.

^ Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 254-255.

^ abc Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 145.

^ Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 282.

^ abc Makkai 1994a, p. 25.

^ Master Roger's Epistle (ch. 4), p. 143.

^ Engel 2001, pp. 96–98.

^ ab Curta 2006, p. 409.

^ abcdefghij Cartledge 2011, p. 29.

^ Grousset 1970, p. 264.

^ abcde Curta 2006, p. 410.

^ Chambers 1979, p. 91.

^ Engel 2001, p. 99.

^ Master Roger's Epistle (ch. 3), p. 141.

^ Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 256.

^ abc Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 147.

^ abc Makkai 1994a, p. 26.

^ Engel 2001, pp. 99–100.

^ abcd Engel 2001, p. 100.

^ Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, pp. 147–148.

^ Kristó 2003, pp. 158–159.

^ Master Roger's Epistle (ch. 28), p. 181.

^ Chambers 1979, pp. 95, 102–104.

^ Kirschbaum 1996, p. 44.

^ abcdefg Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 148.

^ ab Molnár 2001, p. 34.

^ ab Tanner 2010, p. 21.

^ Curta 2006, pp. 409, 411.

^ abcdef Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 149.

^ Grousset 1970, pp. 267–268.

^ abc Cartledge 2011, p. 30.

^ Fine 1994, pp. 150–151.

^ abcde Engel 2001, p. 104.

^ ab Makkai 1994a, p. 27.

^ ab Engel 2001, p. 103.

^ ab Kontler 1999, p. 78.

^ ab Engel 2001, pp. 103–104.

^ ab Sălăgean 2005, p. 234.

^ Sălăgean 2005, p. 235.

^ Curta 2006, p. 414.

^ Engel 2001, pp. 104–105.

^ Bartl et al. 2002, p. 32.

^ ab Engel 2001, p. 105.

^ Makkai 1994a, p. 29.

^ abc Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 151.

^ Engel 2001, p. 112.

^ Molnár 2001, pp. 37–38.

^ abc Cartledge 2011, p. 31.

^ Kristó & Makk 1996, pp. 257, 263, 268.

^ ab Kontler 1999, p. 81.

^ abc Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 163.

^ Molnár 2001, p. 36.

^ Molnár 2001, p. 37.

^ Tanner 2010, p. 22.

^ Fine 1994, p. 152.

^ Almási 1994, p. 93.

^ ab Engel 2001, p. 106.

^ ab Bárány 2012, p. 353.

^ Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 263.

^ ab Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 150.

^ abcd Žemlička 2011, p. 107.

^ Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 264.

^ ab Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 152.

^ abc Kristó 2003, p. 176.

^ ab Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 153.

^ Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, pp. 153–154.

^ abcd Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 154.

^ Žemlička 2011, p. 108.

^ ab Fine 1994, p. 159.

^ ab Bárány 2012, p. 355.

^ abc Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 155.

^ ab Kristó 2003, p. 177.

^ ab Makkai 1994a, p. 30.

^ abc Kristó 2003, p. 179.

^ Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 109.

^ abc Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 157.

^ abc Klaniczay 2002, p. 277.

^ ab Kontler 1999, p. 99.

^ abc Engel 2001, p. 97.

^ ab Klaniczay 2002, p. 231.

^ Kristó 2003, pp. 180–181.

^ ab Fine 1994, p. 174.

^ Zsoldos 2007, p. 18.

^ abcdefgh Sălăgean 2005, p. 236.

^ abc Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 265.

^ ab Zsoldos 2007, p. 11.

^ abcdefgh Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 158.

^ Zsoldos 2007, p. 21.

^ Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 159.

^ Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 160.

^ The Laws of the Medieval Kingdom of Hungary, 1000–1301 (1267:Preamble), p. 40.

^ abc Engel 2001, p. 120.

^ ab Bartl et al. 2002, p. 33.

^ abc Fine 1994, p. 203.

^ Kristó 2003, p. 182.

^ ab Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 162.

^ Engel 2001, p. 107.

^ Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, pp. 163–164.

^ ab Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 164.

^ Kristó & Makk 1996, pp. 246, 248, 257, Appendices 4–5.

^ Almási 1994, p. 234.

^ Runciman 1989, p. 345, Appendix III.

^ ab Kristó 2003, p. 248.

^ abcdef Klaniczay 2002, p. 439.

^ Klaniczay 2002, p. 207.

^ ab Kristó 2003, p. 248, Appendix 5.

^ Kristó 2003, pp. 248, 263, Appendix 5.

^ ab Kristó 2003, p. Appendix 5.

^ Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, pp. 190–191.

^ Kristó 2003, p. 263, Appendix 5.

^ Kristó 2003, p. 257, Appendix 5.

^ Kristó 2003, p. 271.

^ Zsoldos 2007, pp. 13–15.

^ ab Klaniczay 2002, p. 232.

^ Diós, István. "Árpádházi Boldog Kinga [Blessed Kunigunda of the Árpáds]". A szentek élete [Lives of Saints]. Szent István társulat. Retrieved 8 April 2014..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Diós, István. "Árpádházi Boldog Jolán [Blessed Yolanda of the Árpáds]". A szentek élete [Lives of Saints]. Szent István társulat. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

^ Diós, István. "Árpádházi Szent Margit [Saint Margaret of the Árpáds]". A szentek élete [Lives of Saints]. Szent István társulat. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

^ Kristó & Makk 1996, pp. 248, 263, Appendices 4–5.

^ Cartledge 2011, pp. 30–31.

^ The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 178.126), p. 140.

^ The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 179.127), p. 141.

Sources

Primary sources

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Master Roger's Epistle to the Sorrowful Lament upon the Destruction of the Kingdom of Hungary by the Tatars (Translated and Annotated by János M. Bak and Martyn Rady) (2010). In Rady, Martyn; Veszprémy, László; Bak, János M. (2010). Anonymus and Master Roger. CEU Press.

ISBN 978-963-9776-95-1.

The Galician-Volynian Chronicle (An annoted translation by George A. Perfecky) (1973). Wilhelm Fink Verlag.

The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle: Chronica de Gestis Hungarorum (Edited by Dezső Dercsényi) (1970). Corvina, Taplinger Publishing.

ISBN 0-8008-4015-1.

The Laws of the Medieval Kingdom of Hungary, 1000–1301 (Translated and Edited by János M. Bak, György Bónis, James Ross Sweeney with an essay on previous editions by Andor Czizmadia, Second revised edition, In collaboration with Leslie S. Domonkos) (1999). Charles Schlacks, Jr. Publishers. pp. 1–11.

ISBN 1-884445-29-2.

Secondary sources

Almási, Tibor (1994). "IV. Béla; Gertrúd". In Kristó, Gyula; Engel, Pál; Makk, Ferenc. Korai magyar történeti lexikon (9–14. század) [Encyclopedia of the Early Hungarian History (9th–14th centuries)] (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 92–93, 234. ISBN 963-05-6722-9.

Bárány, Attila (2012). "The Expansion of the Kingdom of Hungary in the Middle Ages (1000–1490)". In Berend, Nóra. The Expansion of Central Europe in the Middle Ages. Ashgate Variorum. pp. 333–380. ISBN 978-1-4094-2245-7.

Bartl, Július; Čičaj, Viliam; Kohútova, Mária; Letz, Róbert; Segeš, Vladimír; Škvarna, Dušan (2002). Slovak History: Chronology & Lexicon. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, Slovenské Pedegogické Nakladatel'stvo. ISBN 0-86516-444-4.

Cartledge, Bryan (2011). The Will to Survive: A History of Hungary. C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-1-84904-112-6.

Chambers, James (1979). The Devil's Horsemen: The Mongol Invasion of Europe. Atheneum. ISBN 978-0-7858-1567-9.

Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89452-4.

Engel, Pál (2001). The Realm of St Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895–1526. I.B. Tauris Publishers. ISBN 1-86064-061-3.

Érszegi, Géza; Solymosi, László (1981). "Az Árpádok királysága, 1000–1301 [The Monarchy of the Árpáds, 1000–1301]". In Solymosi, László. Magyarország történeti kronológiája, I: a kezdetektől 1526-ig [Historical Chronology of Hungary, Volume I: From the Beginning to 1526] (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 79–187. ISBN 963-05-2661-1.

Fine, John V. A (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4.

Grousset, René (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

Kirschbaum, Stanislav J. (1996). A History of Slovakia: The Struggle for Survival. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-6929-9.

Klaniczay, Gábor (2002). Holy Rulers and Blessed Princes: Dynastic Cults in Medieval Central Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42018-0.

Kontler, László (1999). Millennium in Central Europe: A History of Hungary. Atlantisz Publishing House. ISBN 963-9165-37-9.

Kristó, Gyula; Makk, Ferenc (1996). Az Árpád-ház uralkodói [Rulers of the House of Árpád] (in Hungarian). I.P.C. Könyvek. ISBN 963-7930-97-3.

Kristó, Gyula (2003). Háborúk és hadviselés az Árpádok korában [Wars and Tactics under the Árpáds] (in Hungarian). Szukits Könyvkiadó. ISBN 963-9441-87-2.

Magaš, Branka (2007). Croatia Through History. SAQI. ISBN 978-0-86356-775-9.

Makkai, László (1994a). "Transformation into a Western-type state, 1196–1301". In Sugar, Peter F.; Hanák, Péter; Frank, Tibor. A History of Hungary. Indiana University Press. pp. 23–33. ISBN 963-7081-01-1.

Makkai, László (1994b). "The Emergence of the Estates (1172–1526)". In Köpeczi, Béla; Barta, Gábor; Bóna, István; Makkai, László; Szász, Zoltán; Borus, Judit. History of Transylvania. Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 178–243. ISBN 963-05-6703-2.

Molnár, Miklós (2001). A Concise History of Hungary. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66736-4.

Runciman, Steven (1989). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East 1100–1187. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-06162-8.

Sălăgean, Tudor (2005). "Regnum Transilvanum. The assertion of the Congregational Regime". In Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Nägler, Thomas. The History of Transylvania, Vol. I. (Until 1541). Romanian Cultural Institute (Center for Transylvanian Studies). pp. 233–246. ISBN 973-7784-00-6.

Tanner, Marcus (2010). Croatia: A Nation Forged in War. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-16394-0.

Žemlička, Josef (2011). "The Realm of Přemysl Ottokar II and Wenceslas II". In Pánek, Jaroslav; Tůma, Oldřich. A History of the Czech Lands. Charles University in Prague. pp. 106–116. ISBN 978-80-246-1645-2.

Zsoldos, Attila (2007). Családi ügy: IV. Béla és István ifjabb király viszálya az 1260-as években [A family affair: The Conflict between Béla IV and King-junior Stephen in the 1260s] (in Hungarian). História, MTA Történettudományi Intézete. ISBN 978-963-9627-15-4.

External links

Béla IV Encyclopædia Britannica

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Béla IV of Hungary. |

Béla IV of Hungary House of Árpád Born: 29 November 1206 Died: 3 May 1270 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

Vacant Title last held by Andrew | Duke of Slavonia 1220–1226 | Succeeded by Coloman |

New creation | Duke of Transylvania 1226–1235 | Vacant Title next held by Stephen |

| Preceded by Andrew II | King of Hungary and Croatia 1235–1270 | Succeeded by Stephen V |

| Preceded by Ottokar as opposing claimant | Duke of Styria 1254–1258 | |

Comments

Post a Comment