Heat capacity

| Thermodynamics | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The classical Carnot heat engine | |||||||||||||||||||||

Branches

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Laws

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Systems

| |||||||||||||||||||||

System properties Note: Conjugate variables in italics

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Material properties

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Equations

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Potentials

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Scientists

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Heat capacity or thermal capacity is a measurable physical quantity equal to the ratio of the heat added to (or removed from) an object to the resulting temperature change.[1] The unit of heat capacity is joule per kelvin JK{displaystyle mathrm {tfrac {J}{K}} }

Heat capacity is an extensive property of matter, meaning that it is proportional to the size of the system. When expressing the same phenomenon as an intensive property, the heat capacity is divided by the amount of substance, mass, or volume, thus the quantity is independent of the size or extent of the sample. The molar heat capacity is the heat capacity per unit amount (SI unit: mole) of a pure substance, and the specific heat capacity, often called simply specific heat, is the heat capacity per unit mass of a material. Nonetheless some authors use the term specific heat to refer to the ratio of the specific heat capacity of a substance at any given temperature to the specific heat capacity of another substance at a reference temperature, much in the fashion of specific gravity. In some engineering contexts, the volumetric heat capacity is used.

Temperature reflects the average randomized kinetic energy of constituent particles of matter (i.e., atoms or molecules) relative to the centre of mass of the system, while heat is the transfer of energy across a system boundary into the body other than by work or matter transfer. Translation, rotation, and vibration of atoms represent the degrees of freedom of motion which classically contribute to the heat capacity of gases, while only vibrations are needed to describe the heat capacities of most solids,[2] as shown by the Dulong–Petit law. Other contributions can come from magnetic[3] and electronic[4]

degrees of freedom in solids, but these rarely make substantial contributions.

For quantum mechanical reasons, at any given temperature, some of these degrees of freedom may be unavailable, or only partially available, to store thermal energy. In such cases, the heat capacity is a fraction of the maximum. As the temperature approaches absolute zero, the heat capacity of a system approaches zero because of loss of available degrees of freedom. Quantum theory can be used to quantitatively predict the heat capacity of simple systems.

.mw-parser-output .toclimit-2 .toclevel-1 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-3 .toclevel-2 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-4 .toclevel-3 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-5 .toclevel-4 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-6 .toclevel-5 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-7 .toclevel-6 ul{display:none}

Contents

1 History

2 Units

2.1 Extensive properties

2.2 Intensive properties

2.3 Alternative unit systems

3 Measurement

3.1 Calculation from first principles

3.2 Thermodynamic relations and definition of heat capacity

3.3 Relation between heat capacities

3.3.1 Ideal gas

3.4 Specific heat capacity

3.5 Polytropic heat capacity

3.6 Dimensionless heat capacity

3.7 Heat capacity at absolute zero

3.8 Negative heat capacity (stars)

4 Theory

4.1 Factors that affect specific heat capacity

4.1.1 Degrees of freedom

4.1.2 Example of temperature-dependent specific heat capacity, in a diatomic gas

4.1.3 Per mole of different units

4.1.3.1 Per mole of molecules

4.1.3.2 Per mole of atoms

4.1.4 Corollaries of these considerations for solids (volume-specific heat capacity)

4.1.5 Other factors

4.1.5.1 Hydrogen bonds

4.1.5.2 Impurities

4.2 The simple case of the monatomic gas

4.3 Diatomic gas

4.4 General gas phase

4.5 The storage of energy into degrees of freedom

4.6 The effect of quantum energy levels in storing energy in degrees of freedom

4.7 Energy storage mode "freeze-out" temperatures

4.8 Solid phase

4.9 Liquid phase

5 Table of specific heat capacities

6 Mass heat capacity of building materials

7 See also

8 Notes

9 References

10 Further reading

11 External links

History

In a previous theory of heat common in the early modern period, heat was thought to be a measurement of an invisible fluid, known as the caloric. Bodies were capable of holding a certain amount of this fluid, hence the term heat capacity, named and first investigated by Scottish chemist Joseph Black in the 1750s.[5]

Since the development of thermodynamics in the 18th and 19th centuries, scientists have abandoned the idea of a physical caloric, and instead understand heat as a manifestation of a system's internal energy. Heat is no longer considered a fluid, but rather a transfer of disordered energy. Nevertheless, at least in English, the term "heat capacity" survives. In some other languages, the term thermal capacity is preferred, and it is also sometimes used in English.

Units

Extensive properties

In the International System of Units, heat capacity has the unit joules per Kelvin (J/K). The heat capacity (symbol C) of a system is defined as the ratio of heat transferred to or from the system and the resulting change in temperature in the system,

- C(T)=δQdT,{displaystyle C(T)={frac {delta Q}{dT}},}

where the symbol δ designates heat as a path function.

If the temperature change is sufficiently small the heat capacity may be assumed to be constant:

- C=QΔT.{displaystyle C={frac {Q}{Delta T}}.}

Heat capacity is an extensive property, meaning it depends on the extent or size of the physical system studied. A sample containing twice the amount of substance as another sample requires the transfer of twice the amount of heat (Q{displaystyle Q}

Intensive properties

For many purposes it is more convenient to report heat capacity as an intensive property, an intrinsic characteristic of a particular substance. In practice, this is most often an expression of the property in relation to a unit of mass; in science and engineering, such properties are often prefixed with the term specific.[6] International standards now recommend that specific heat capacity always refer to division by mass.[7] The units for the specific heat capacity are [c]=Jkg⋅K{displaystyle [c]=mathrm {tfrac {J}{kgcdot K}} }![[c]=mathrm {tfrac {J}{kgcdot K}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/59f89f7dd4fd480785b25d2b47db12d21704d6ec)

In chemistry, heat capacity is often specified relative to one mole, the unit of amount of substance, and is called the molar heat capacity. It has the unit [Cmol]=Jmol⋅K{displaystyle [C_{mathrm {mol} }]=mathrm {tfrac {J}{molcdot K}} }![[C_{mathrm {mol} }]=mathrm {tfrac {J}{molcdot K}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c6ce0541306c6ba08bf56f477816d781fbce85bb)

For some considerations it is useful to specify the volume-specific heat capacity, commonly called volumetric heat capacity, which is the heat capacity per unit volume and has SI units [s]=Jm3⋅K{displaystyle [s]=mathrm {tfrac {J}{m^{3}cdot K}} }![[s]=mathrm {tfrac {J}{m^{3}cdot K}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3403f2cde8935ae34e3783a4436aa4de53c51f51)

Alternative unit systems

While SI units are the most widely used, some countries and industries also use other systems of measurement. One older unit of heat is the kilogram-calorie (Cal), originally defined as the energy required to raise the temperature of one kilogram of water by one degree Celsius, typically from 14.5 to 15.5 °C. The specific average heat capacity of water on this scale would therefore be exactly 1 Cal/(C°⋅kg). However, due to the temperature-dependence of the specific heat, a large number of different definitions of the calorie came into being. Whilst once it was very prevalent, especially its smaller cgs variant the gram-calorie (cal), defined thus the specific heat of water would be 1 cal/(K⋅g), in most fields the use of the calorie is now archaic.

In the United States other units of measure for heat capacity may be quoted in disciplines such as construction, civil engineering, and chemical engineering. A still common system is the English Engineering Units in which the mass reference is pound mass and the temperature is specified in degrees Fahrenheit or Rankine. One (rare) unit of heat is the pound calorie (lb-cal), defined as the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of one pound of water by one degree Celsius. On this scale the specific heat of water would be 1 lb-cal/(K⋅lb). More common is the British thermal unit, the standard unit of heat in the U.S. construction industry. This is defined such that the specific heat of water is 1 BTU/(F°⋅lb).

The path integral Monte Carlo method is a numerical approach for determining the values of heat capacity, based on quantum dynamical principles. However, good approximations can be made for gases in many states using simpler methods outlined below. For many solids composed of relatively heavy atoms (atomic number > iron), at non-cryogenic temperatures, the heat capacity at room temperature approaches 3R = 24.94 joules per kelvin per mole of atoms (Dulong–Petit law, R is the gas constant). Low temperature approximations for both gases and solids at temperatures less than their characteristic Einstein temperatures or Debye temperatures can be made by the methods of Einstein and Debye discussed below.

Water (liquid): CP = 4185.5 J/(kg⋅K) (15 °C, 101.325 kPa)

Water (liquid): CVH = 74.539 J/(mol⋅K) (25 °C)

For liquids and gases, it is important to know the pressure to which given heat capacity data refer. Most published data are given for standard pressure. However, different standard conditions for temperature and pressure have been defined by different organizations. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) changed its recommendation from one atmosphere to the round value 100 kPa (≈750.062 Torr).[notes 1]

Measurement

It may appear that the way to measure heat capacity is to add a known amount of heat to an object, and measure the change in temperature. This works reasonably well for many solids. For precise measurements, especially for gases, other aspects of measurement become critical.

The heat capacity can be affected by many of the state variables that describe the thermodynamic system under study. These include the starting and ending temperature, as well as the pressure and the volume of the system before and after heat is added. So rather than a single way to measure heat capacity, there are actually several slightly different measurements of heat capacity. The most commonly used methods for measurement are to hold the object either at constant pressure

(CP) or at constant volume (CV). Gases and liquids are typically also measured at constant volume. Measurements under constant pressure produce larger values than those at constant volume because the constant pressure values also include heat energy that is used to do work to expand the substance against the constant pressure as its temperature increases. This difference is particularly notable in gases where values under constant pressure are typically 30% to 66.7% greater than those at constant volume. Hence the heat capacity ratio of gases is typically between 1.3 and 1.67.[8]

The specific heat capacities of substances comprising molecules (as distinct from monatomic gases) are not fixed constants and vary somewhat depending on temperature. Accordingly, the temperature at which the measurement is made is usually also specified. Examples of two common ways to cite the specific heat of a substance are as follows:[9]

- Water (liquid): CP = 4185.5 J/(kg⋅K) (15 °C, 101.325 kPa)

- Water (liquid): CVH = 74.539 J/(mol⋅K) (25 °C)

For liquids and gases, it is important to know the pressure to which given heat capacity data refer. Most published data are given for standard pressure. However, quite different standard conditions for temperature and pressure have been defined by different organizations. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) changed its recommendation from one atmosphere to the round value 100 kPa (≈750.062 Torr).[notes 1]

Calculation from first principles

The path integral Monte Carlo method is a numerical approach for determining the values of heat capacity, based on quantum dynamical principles. However, good approximations can be made for gases in many states using simpler methods outlined below. For many solids composed of relatively heavy atoms (atomic number > iron), at non-cryogenic temperatures, the heat capacity at room temperature approaches 3R = 24.94 joules per kelvin per mole of atoms (Dulong–Petit law, R is the gas constant). Low temperature approximations for both gases and solids at temperatures less than their characteristic Einstein temperatures or Debye temperatures can be made by the methods of Einstein and Debye discussed below.

Thermodynamic relations and definition of heat capacity

The internal energy of a closed system changes either by adding heat to the system or by the system performing work. Written mathematically we have

- Δesystem=ein−eout,{displaystyle Delta e_{text{system}}=e_{text{in}}-e_{text{out}},}

or

- dU=δQ−δW.{displaystyle mathrm {d} U=delta Q-delta W.}

For work as a result of an increase of the system volume we may write

- dU=δQ−PdV.{displaystyle mathrm {d} U=delta Q-P,mathrm {d} V.}

If the heat is added at constant volume, then the second term of this relation vanishes, and one readily obtains

- (∂U∂T)V=(∂Q∂T)V=CV.{displaystyle left({frac {partial U}{partial T}}right)_{V}=left({frac {partial Q}{partial T}}right)_{V}=C_{V}.}

This defines the heat capacity at constant volume, CV, which is also related to changes in internal energy. Another useful quantity is the heat capacity at constant pressure, CP. This quantity refers to the change in the enthalpy of the system, which is given by

- H=U+PV.{displaystyle H=U+PV.}

A small change in the enthalpy can be expressed as

- dH=dU+d(PV),{displaystyle mathrm {d} H=mathrm {d} U+,mathrm {d} (PV),}

- dH=δQ−δW+d(PV),{displaystyle mathrm {d} H=delta Q-delta W+,mathrm {d} (PV),}

- dH=δQ−PdV+PdV+VdP,{displaystyle mathrm {d} H=delta Q-Pmathrm {d} V+,Pmathrm {d} V+,Vmathrm {d} P,}

- dH=δQ+VdP,{displaystyle mathrm {d} H=delta Q+V,mathrm {d} P,}

and therefore, at constant pressure, we have

- (∂H∂T)P=(∂Q∂T)P=CP.{displaystyle left({frac {partial H}{partial T}}right)_{P}=left({frac {partial Q}{partial T}}right)_{P}=C_{P}.}

These two equations:

- (∂U∂T)V=(∂Q∂T)V=CV,{displaystyle left({frac {partial U}{partial T}}right)_{V}=left({frac {partial Q}{partial T}}right)_{V}=C_{V},}

- (∂H∂T)P=(∂Q∂T)P=CP{displaystyle left({frac {partial H}{partial T}}right)_{P}=left({frac {partial Q}{partial T}}right)_{P}=C_{P}}

are property relations and are therefore independent of the type of process. In other words, they are valid for any substance going through any process. Both the internal energy and enthalpy of a substance can change with the transfer of energy in many forms i.e., heat.[10]

Relation between heat capacities

Measuring the heat capacity, sometimes referred to as specific heat, at constant volume can be prohibitively difficult for liquids and solids. That is, small temperature changes typically require large pressures to maintain a liquid or solid at constant volume, implying that the containing vessel must be nearly rigid or at least very strong (see coefficient of thermal expansion and compressibility). Instead, it is easier to measure the heat capacity at constant pressure (allowing the material to expand or contract freely) and solve for the heat capacity at constant volume using mathematical relationships derived from the basic thermodynamic laws. Starting from the fundamental thermodynamic relation one can show that

- CP−CV=T(∂P∂T)V,n(∂V∂T)P,n,{displaystyle C_{P}-C_{V}=Tleft({frac {partial P}{partial T}}right)_{V,n}left({frac {partial V}{partial T}}right)_{P,n},}

where the partial derivatives are taken at constant volume and constant number of particles, and constant pressure and constant number of particles, respectively.

This can also be rewritten as

- CP−CV=VTα2βT,{displaystyle C_{P}-C_{V}=VT{frac {alpha ^{2}}{beta _{T}}},}

where

α{displaystyle alpha }is the coefficient of thermal expansion,

βT{displaystyle beta _{T}}is the isothermal compressibility.

The heat capacity ratio, or adiabatic index, is the ratio of the heat capacity at constant pressure to heat capacity at constant volume. It is sometimes also known as the isentropic expansion factor.

Ideal gas

[11]

For an ideal gas, evaluating the partial derivatives above according to the equation of state, where R is the gas constant, for an ideal gas

- PV=nRT,{displaystyle PV=nRT,}

- CP−CV=T(∂P∂T)V,n(∂V∂T)P,n,{displaystyle C_{P}-C_{V}=Tleft({frac {partial P}{partial T}}right)_{V,n}left({frac {partial V}{partial T}}right)_{P,n},}

- P=nRTV⇒(∂P∂T)V,n=nRV,{displaystyle P={frac {nRT}{V}}Rightarrow left({frac {partial P}{partial T}}right)_{V,n}={frac {nR}{V}},}

- V=nRTP⇒(∂V∂T)P,n=nRP.{displaystyle V={frac {nRT}{P}}Rightarrow left({frac {partial V}{partial T}}right)_{P,n}={frac {nR}{P}}.}

Substituting

- T(∂P∂T)V,n(∂V∂T)P,n=TnRVnRP=nRTVnRP=PnRP=nR,{displaystyle Tleft({frac {partial P}{partial T}}right)_{V,n}left({frac {partial V}{partial T}}right)_{P,n}=T{frac {nR}{V}}{frac {nR}{P}}={frac {nRT}{V}}{frac {nR}{P}}=P{frac {nR}{P}}=nR,}

this equation reduces simply to Mayer's relation:

- CP,m−CV,m=R.{displaystyle C_{P,m}-C_{V,m}=R.}

The differences in heat capacities as defined by the above Mayer relation is only exact for an ideal gas and would be different for any real gas.

Specific heat capacity

The specific heat capacity of a material on a per mass basis is

- c=∂C∂m,{displaystyle c={frac {partial C}{partial m}},}

which in the absence of phase transitions is equivalent to

- c=Em=Cm=CρV,{displaystyle c=E_{m}={frac {C}{m}}={frac {C}{rho V}},}

where

C{displaystyle C}is the heat capacity of a body made of the material in question,

m{displaystyle m}is the mass of the body,

V{displaystyle V}is the volume of the body,

ρ=mV{displaystyle rho ={frac {m}{V}}}is the density of the material.

For gases, and also for other materials under high pressures, there is need to distinguish between different boundary conditions for the processes under consideration (since values differ significantly between different conditions). Typical processes for which a heat capacity may be defined include isobaric (constant pressure, dP=0{displaystyle {text{d}}P=0}

- cP=(∂C∂m)P,{displaystyle c_{P}=left({frac {partial C}{partial m}}right)_{P},}

- cV=(∂C∂m)V.{displaystyle c_{V}=left({frac {partial C}{partial m}}right)_{V}.}

From the results of the previous section, dividing through by the mass gives the relation

- cP−cV=α2TρβT.{displaystyle c_{P}-c_{V}={frac {alpha ^{2}T}{rho beta _{T}}}.}

A related parameter to c{displaystyle c}

- cm=Cm=cvolumetricρ.{displaystyle c_{m}={frac {C}{m}}={frac {c_{text{volumetric}}}{rho }}.}

For pure homogeneous chemical compounds with established molecular or molar mass, or a molar quantity, heat capacity as an intensive property can be expressed on a per-mole basis instead of a per-mass basis by the following equations analogous to the per mass equations:

CP,m=(∂C∂n)P{displaystyle C_{P,m}=left({frac {partial C}{partial n}}right)_{P}}= molar heat capacity at constant pressure,

CV,m=(∂C∂n)V{displaystyle C_{V,m}=left({frac {partial C}{partial n}}right)_{V}}= molar heat capacity at constant volume,

where n is the number of moles in the body or thermodynamic system. One may refer to such a per-mole quantity as molar heat capacity to distinguish it from specific heat capacity on a per-mass basis.

Polytropic heat capacity

The polytropic heat capacity is calculated at processes if all the thermodynamic properties (pressure, volume, temperature) change:

Ci,m=(∂C∂n){displaystyle C_{i,m}=left({frac {partial C}{partial n}}right)}= molar heat capacity at polytropic process.

The most important polytropic processes run between the adiabatic and the isotherm functions, the polytropic index is between 1 and the adiabatic exponent (γ or κ).

Dimensionless heat capacity

The dimensionless heat capacity of a material is

- C∗=CnR=CNk,{displaystyle C^{*}={frac {C}{nR}}={frac {C}{Nk}},}

where

C is the heat capacity of a body made of the material in question (J/K),

n is the amount of substance in the body (mol),

R is the gas constant (J/(K⋅mol)),

N is the number of molecules in the body (dimensionless),

k is Boltzmann's constant (J/(K⋅molecule)).

In the ideal gas article, dimensionless heat capacity C∗{displaystyle C^{*}}

More generally, the dimensionless heat capacity relates the logarithmic increase in temperature to the increase in the dimensionless entropy per particle S∗=S/Nk{displaystyle S^{*}=S/Nk}

- C∗=dS∗d(lnT).{displaystyle C^{*}={frac {{text{d}}S^{*}}{{text{d}}(ln T)}}.}

Alternatively, using base-2 logarithms, C* relates the base-2 logarithmic increase in temperature to the increase in the dimensionless entropy measured in bits.[12]

Heat capacity at absolute zero

From the definition of entropy

- TdS=δQ,{displaystyle T,{text{d}}S=delta Q,}

the absolute entropy can be calculated by integrating from zero to the final temperature Tf:

- S(Tf)=∫T=0TfδQT=∫0TfδQdTdTT=∫0TfC(T)dTT.{displaystyle S(T_{text{f}})=int _{T=0}^{T_{text{f}}}{frac {delta Q}{T}}=int _{0}^{T_{text{f}}}{frac {delta Q}{{text{d}}T}}{frac {{text{d}}T}{T}}=int _{0}^{T_{text{f}}}C(T),{frac {{text{d}}T}{T}}.}

The heat capacity must be zero at zero temperature for the above integral not to yield an infinite absolute entropy, which would violate the third law of thermodynamics. One of the strengths of the Debye model is that (unlike the preceding Einstein model) it predicts the proper mathematical form of the approach of heat capacity toward zero, as absolute zero temperature is approached.

Negative heat capacity (stars)

Most physical systems exhibit a positive heat capacity. However, even though it can seem paradoxical at first,[13][14] there are some systems for which the heat capacity is negative. These are inhomogeneous systems that do not meet the strict definition of thermodynamic equilibrium. They include gravitating objects such as stars and galaxies, and also sometimes some nano-scale clusters of a few tens of atoms, close to a phase transition.[15] A negative heat capacity can result in a negative temperature.

According to the virial theorem, for a self-gravitating body like a star or an interstellar gas cloud, the average potential energy Upot and the average kinetic energy Ukin are locked together in the relation

- Upot=−2Ukin.{displaystyle U_{text{pot}}=-2U_{text{kin}}.}

The total energy U (= Upot + Ukin) therefore obeys

- U=−Ukin.{displaystyle U=-U_{text{kin}}.}

If the system loses energy, for example, by radiating energy into space, the average kinetic energy actually increases. If a temperature is defined by the average kinetic energy, then the system therefore can be said to have a negative heat capacity.[16]

A more extreme version of this occurs with black holes. According to black-hole thermodynamics, the more mass and energy a black hole absorbs, the colder it becomes. In contrast, if it is a net emitter of energy, through Hawking radiation, it will become hotter and hotter until it boils away.

Theory

Factors that affect specific heat capacity

Molecules undergo many characteristic internal vibrations. Potential energy stored in these internal degrees of freedom contributes to a sample's energy content, [17][18] but not to its temperature. More internal degrees of freedom tend to increase a substance's specific heat capacity, so long as temperatures are high enough to overcome quantum effects.

For any given substance, the heat capacity of a body is directly proportional to the amount of substance it contains (measured in terms of mass or moles or volume). Doubling the amount of substance in a body doubles its heat capacity, etc.

However, when this effect has been corrected for, by dividing the heat capacity by the quantity of substance in a body, the resulting specific heat capacity is a function of the structure of the substance itself. In particular, it depends on the number of degrees of freedom that are available to the particles in the substance; each independent degree of freedom allows the particles to store thermal energy. The translational kinetic energy of substance particles which manifests as temperature change is only one of the many possible degrees of freedom, and thus the larger the number of degrees of freedom available to the particles of a substance other than translational kinetic energy, the larger will be the specific heat capacity for the substance. For example, rotational kinetic energy of gas molecules stores heat energy in a way that increases heat capacity, since this energy does not contribute to temperature.

In addition, quantum effects require that whenever energy be stored in any mechanism associated with a bound system which confers a degree of freedom, it must be stored in certain minimal-sized deposits (quanta) of energy, or else not stored at all. Such effects limit the full ability of some degrees of freedom to store energy when their lowest energy storage quantum amount is not easily supplied at the average energy of particles at a given temperature. In general, for this reason, specific heat capacities tend to fall at lower temperatures where the average thermal energy available to each particle degree of freedom is smaller, and thermal energy storage begins to be limited by these quantum effects. Due to this process, as temperature falls toward absolute zero, so also does heat capacity.

Degrees of freedom

Molecules are quite different from the monatomic gases like helium and argon. With monatomic gases, thermal energy comprises only translational motions. Translational motions are ordinary, whole-body movements in 3D space whereby particles move about and exchange energy in collisions—like rubber balls in a vigorously shaken container (see animation here [19]). These simple movements in the three dimensions of space mean individual atoms have three translational degrees of freedom. A degree of freedom is any form of energy in which heat transferred into an object can be stored. This can be in translational kinetic energy, rotational kinetic energy, or other forms such as potential energy in vibrational modes. Only three translational degrees of freedom (corresponding to the three independent directions in space) are available for any individual atom, whether it is free, as a monatomic molecule, or bound into a polyatomic molecule.

As to rotation about an atom's axis (again, whether the atom is bound or free), its energy of rotation is proportional to the moment of inertia for the atom, which is extremely small compared to moments of inertia of collections of atoms. This is because almost all of the mass of a single atom is concentrated in its nucleus, which has a radius too small to give a significant moment of inertia. In contrast, the spacing of quantum energy levels for a rotating object is inversely proportional to its moment of inertia, and so this spacing becomes very large for objects with very small moments of inertia. For these reasons, the contribution from rotation of atoms on their axes is essentially zero in monatomic gases, because the energy spacing of the associated quantum levels is too large for significant thermal energy to be stored in rotation of systems with such small moments of inertia. For similar reasons, axial rotation around bonds joining atoms in diatomic gases (or along the linear axis in a linear molecule of any length) can also be neglected as a possible "degree of freedom" as well, since such rotation is similar to rotation of monatomic atoms, and so occurs about an axis with a moment of inertia too small to be able to store significant heat energy.

In polyatomic molecules, other rotational modes may become active, due to the much higher moments of inertia about certain axes which do not coincide with the linear axis of a linear molecule. These modes take the place of some translational degrees of freedom for individual atoms, since the atoms are moving in 3-D space, as the molecule rotates. The narrowing of quantum mechanically determined energy spacing between rotational states results from situations where atoms are rotating around an axis that does not connect them, and thus form an assembly that has a large moment of inertia. This small difference between energy states allows the kinetic energy of this type of rotational motion to store heat energy at ambient temperatures. Furthermore, internal vibrational degrees of freedom also may become active (these are also a type of translation, as seen from the view of each atom). In summary, molecules are complex objects with a population of atoms that may move about within the molecule in a number of different ways (see animation at right), and each of these ways of moving is capable of storing energy if the temperature is sufficient.

The heat capacity of molecular substances (on a "per-atom" or atom-molar, basis) does not exceed the heat capacity of monatomic gases, unless vibrational modes are brought into play. The reason for this is that vibrational modes allow energy to be stored as potential energy in inter-atomic bonds in a molecule, which are not available to atoms in monatomic gases. Up to about twice as much energy (on a per-atom basis) per unit of temperature increase can be stored in a solid as in a monatomic gas, by this mechanism of storing energy in the potentials of interatomic bonds. This gives many solids about twice the atom-molar heat capacity at room temperature of monatomic gases.

However, quantum effects heavily affect the actual ratio at lower temperatures (i.e., much lower than the melting temperature of the solid), especially in solids with light and tightly bound atoms (e.g., beryllium metal or diamond). Polyatomic gases store intermediate amounts of energy, giving them a "per-atom" heat capacity that is between that of monatomic gases (3⁄2 R per mole of atoms, where R is the ideal gas constant), and the maximum of fully excited warmer solids (3 R per mole of atoms). For gases, heat capacity never falls below the minimum of 3⁄2 R per mole (of molecules), since the kinetic energy of gas molecules is always available to store at least this much thermal energy. However, at cryogenic temperatures in solids, heat capacity falls toward zero, as temperature approaches absolute zero.

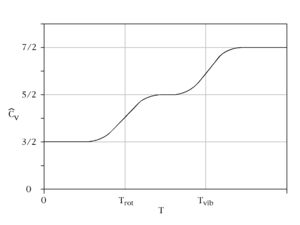

Example of temperature-dependent specific heat capacity, in a diatomic gas

To illustrate the role of various degrees of freedom in storing heat, we may consider nitrogen, a diatomic molecule that has five active degrees of freedom at room temperature: the three comprising translational motions plus two rotational degrees of freedom internally. Although the constant-volume molar heat capacity of nitrogen at this temperature is five-thirds that of monatomic gases, on a per-mole of atoms basis, it is five-sixths that of a monatomic gas. The reason for this is the loss of a degree of freedom due to the bond when it does not allow storage of thermal energy. Two separate nitrogen atoms would have a total of six degrees of freedom—the three translational degrees of freedom of each atom. When the atoms are bonded the molecule will still only have three translational degrees of freedom, as the two atoms in the molecule move as one. However, the molecule cannot be treated as a point object, and the moment of inertia has increased sufficiently about two axes to allow two rotational degrees of freedom to be active at room temperature to give five degrees of freedom. The moment of inertia about the third axis remains small, as this is the axis passing through the centres of the two atoms, and so is similar to the small moment of inertia for atoms of a monatomic gas. Thus, this degree of freedom does not act to store heat, and does not contribute to the heat capacity of nitrogen. The heat capacity per atom for nitrogen (5/2 R per mole molecules = 5/4 R per mole atoms) is therefore less than for a monatomic gas (3/2 R per mole molecules or atoms), so long as the temperature remains low enough that no vibrational degrees of freedom are activated.[20]

At higher temperatures, however, nitrogen gas gains one more degree of internal freedom, as the molecule is excited into higher vibrational modes that store thermal energy. A vibrational degree of freedom contributes a heat capacity of 1/2 R each for kinetic and potential energy, for a total of R. Now the bond is contributing heat capacity, and (because of storage of energy in potential energy) is contributing more than if the atoms were not bonded. With full thermal excitation of bond vibration, the heat capacity per volume, or per mole of gas molecules approaches seven-thirds that of monatomic gases. Significantly, this is seven-sixths of the monatomic gas value on a mole-of-atoms basis, so this is now a higher heat capacity per atom than the monatomic figure, because the vibrational mode enables for diatomic gases allows an extra degree of potential energy freedom per pair of atoms, which monatomic gases cannot possess.[21][22] See thermodynamic temperature for more information on translational motions, kinetic (heat) energy, and their relationship to temperature.

However, even at these large temperatures where gaseous nitrogen is able to store 7/6ths of the energy per atom of a monatomic gas (making it more efficient at storing energy on an atomic basis), it still only stores 7/12 ths of the maximal per-atom heat capacity of a solid, meaning it is not nearly as efficient at storing thermal energy on an atomic basis, as solid substances can be. This is typical of gases, and results because many of the potential bonds which might be storing potential energy in gaseous nitrogen (as opposed to solid nitrogen) are lacking, because only one of the spatial dimensions for each nitrogen atom offers a bond into which potential energy can be stored without increasing the kinetic energy of the atom. In general, solids are most efficient, on an atomic basis, at storing thermal energy (that is, they have the highest per-atom or per-mole-of-atoms heat capacity).

Per mole of different units

Per mole of molecules

When the specific heat capacity, c, of a material is measured (lowercase c means the unit quantity is in terms of mass), different values arise because different substances have different molar masses (essentially, the weight of the individual atoms or molecules). In solids, thermal energy arises due to the number of atoms that are vibrating. "Molar" heat capacity per mole of molecules, for both gases and solids, offer figures which are arbitrarily large, since molecules may be arbitrarily large. Such heat capacities are thus not intensive quantities for this reason, since the quantity of mass being considered can be increased without limit.

Per mole of atoms

Conversely, for molecular-based substances (which also absorb heat into their internal degrees of freedom), massive, complex molecules with high atomic count—like octane—can store a great deal of energy per mole and yet are quite unremarkable on a mass basis, or on a per-atom basis. This is because, in fully excited systems, heat is stored independently by each atom in a substance, not primarily by the bulk motion of molecules.

Thus, it is the heat capacity per-mole-of-atoms, not per-mole-of-molecules, which is the intensive quantity, and which comes closest to being a constant for all substances at high temperatures. This relationship was noticed empirically in 1819, and is called the Dulong–Petit law, after its two discoverers.[23] Historically, the fact that specific heat capacities are approximately equal when corrected by the presumed weight of the atoms of solids, was an important piece of data in favor of the atomic theory of matter.

Because of the connection of heat capacity to the number of atoms, some care should be taken to specify a mole-of-molecules basis vs. a mole-of-atoms basis, when comparing specific heat capacities of molecular solids and gases. Ideal gases have the same numbers of molecules per volume, so increasing molecular complexity adds heat capacity on a per-volume and per-mole-of-molecules basis, but may lower or raise heat capacity on a per-atom basis, depending on whether the temperature is sufficient to store energy as atomic vibration.

In solids, the quantitative limit of heat capacity in general is about 3 R per mole of atoms, where R is the ideal gas constant. This 3 R value is about 24.9 J/mole.K. Six degrees of freedom (three kinetic and three potential) are available to each atom. Each of these six contributes 1⁄2R specific heat capacity per mole of atoms.[24] This limit of 3 R per mole specific heat capacity is approached at room temperature for most solids, with significant departures at this temperature only for solids composed of the lightest atoms which are bound very strongly, such as beryllium (where the value is only of 66% of 3 R), or diamond (where it is only 24% of 3 R). These large departures are due to quantum effects which prevent full distribution of heat into all vibrational modes, when the energy difference between vibrational quantum states is very large compared to the average energy available to each atom from the ambient temperature.

For monatomic gases, the specific heat is only half of 3 R per mole, i.e. (3⁄2R per mole) due to loss of all potential energy degrees of freedom in these gases. For polyatomic gases, the heat capacity will be intermediate between these values on a per-mole-of-atoms basis, and (for heat-stable molecules) would approach the limit of 3 R per mole of atoms, for gases composed of complex molecules, and at higher temperatures at which all vibrational modes accept excitational energy. This is because very large and complex gas molecules may be thought of as relatively large blocks of solid matter which have lost only a relatively small fraction of degrees of freedom, as compared to a fully integrated solid.

For a list of heat capacities per atom-mole of various substances, in terms of R, see the last column of the table of heat capacities below.

Corollaries of these considerations for solids (volume-specific heat capacity)

Since the bulk density of a solid chemical element is strongly related to its molar mass (usually about 3 R per mole, as noted above), there exists a noticeable inverse correlation between a solid's density and its specific heat capacity on a per-mass basis. This is due to a very approximate tendency of atoms of most elements to be about the same size (and constancy of mole-specific heat capacity) resulting in a good correlation between the volume of any given solid chemical element and its total heat capacity. Another way of stating this, is that the volume-specific heat capacity (volumetric heat capacity) of solid elements is roughly a constant. The molar volume of solid elements is very roughly constant, and (even more reliably) so also is the molar heat capacity for most solid substances. These two factors determine the volumetric heat capacity, which as a bulk property may be striking in consistency. For example, the element uranium is a metal which has a density almost 36 times that of the metal lithium, but uranium's specific heat capacity on a volumetric basis (i.e. per given volume of metal) is only 18% larger than lithium's.

Since the volume-specific corollary of the Dulong–Petit specific heat capacity relationship requires that atoms of all elements take up (on average) the same volume in solids, there are many departures from it, with most of these due to variations in atomic size. For instance, arsenic, which is only 14.5% less dense than antimony, has nearly 59% more specific heat capacity on a mass basis. In other words; even though an ingot of arsenic is only about 17% larger than an antimony one of the same mass, it absorbs about 59% more heat for a given temperature rise. The heat capacity ratios of the two substances closely follows the ratios of their molar volumes (the ratios of numbers of atoms in the same volume of each substance); the departure from the correlation to simple volumes in this case is due to lighter arsenic atoms being significantly more closely packed than antimony atoms, instead of similar size. In other words, similar-sized atoms would cause a mole of arsenic to be 63% larger than a mole of antimony, with a correspondingly lower density, allowing its volume to more closely mirror its heat capacity behavior.

Other factors

Hydrogen bonds

Hydrogen-containing polar molecules like ethanol, ammonia, and water have powerful, intermolecular hydrogen bonds when in their liquid phase. These bonds provide another place where heat may be stored as potential energy of vibration, even at comparatively low temperatures. Hydrogen bonds account for the fact that liquid water stores nearly the theoretical limit of 3 R per mole of atoms, even at relatively low temperatures (i.e., near the freezing point of water).

Impurities

In the case of alloys, there are several conditions in which small impurity concentrations can greatly affect the specific heat. Alloys may exhibit marked difference in behaviour even in the case of small amounts of impurities being one element of the alloy; for example impurities in semiconducting ferromagnetic alloys may lead to quite different specific heat properties.[25]

The simple case of the monatomic gas

In the case of a monatomic gas such as helium under constant volume, if it is assumed that no electronic or nuclear quantum excitations occur, each atom in the gas has only 3 degrees of freedom, all of a translational type. No energy dependence is associated with the degrees of freedom that define the position of the atoms. While, in fact, the degrees of freedom corresponding to the momenta of the atoms are quadratic, and thus contribute to the heat capacity. There are N atoms, each of which has 3 components of momentum, which leads to 3N total degrees of freedom. This gives

- CV=(∂U∂T)V=32NkB=32nR,{displaystyle C_{V}=left({frac {partial U}{partial T}}right)_{V}={frac {3}{2}}N,k_{B}={frac {3}{2}}n,R,}

- CV,m=CVn=32R,{displaystyle C_{V,m}={frac {C_{V}}{n}}={frac {3}{2}}R,}

where

CV{displaystyle C_{V}}is the heat capacity at constant volume of the gas,

CV,m{displaystyle C_{V,m}}is the molar heat capacity at constant volume of the gas,

N is the total number of atoms present in the container,

n is the number of moles of atoms present in the container (n is the ratio of N and Avogadro’s number),

R is the ideal gas constant (8.3144621(75) J/(mol⋅K), equal to the product of Boltzmann’s constant kB{displaystyle k_{text{B}}}and Avogadro’s number.

The following table shows experimental molar constant-volume heat-capacity measurements taken for each noble monatomic gas (at 1 atm and 25 °C):

| Monatomic gas | CV, m (J/(mol⋅K)) | CV, m/R |

|---|---|---|

| He | 12.5 | 1.50 |

| Ne | 12.5 | 1.50 |

| Ar | 12.5 | 1.50 |

| Kr | 12.5 | 1.50 |

| Xe | 12.5 | 1.50 |

It is apparent from the table that the experimental heat capacities of the monatomic noble gases agrees with this simple application of statistical mechanics to a very high degree.

The molar heat capacity of a monatomic gas at constant pressure is then

- Cp,m=CV,m+R=52R.{displaystyle C_{p,m}=C_{V,m}+R={frac {5}{2}}R.}

Diatomic gas

Constant-volume specific heat capacity of a diatomic gas (idealised). As temperature increases, heat capacity goes from 3/2 R (translation contribution only), to 5/2 R (translation plus rotation), finally to a maximum of 7/2 R (translation + rotation + vibration)

In the somewhat more complex case of an ideal gas of diatomic molecules, the presence of internal degrees of freedom are apparent. In addition to the three translational degrees of freedom, there are rotational and vibrational degrees of freedom. In general, the number of degrees of freedom, f, in a molecule with na atoms is 3na:

- f=3na.{displaystyle f=3n_{text{a}}.}

Mathematically, there are a total of three rotational degrees of freedom, one corresponding to rotation about each of the axes of three-dimensional space. However, in practice only the existence of two degrees of rotational freedom for linear molecules will be considered. This approximation is valid because the moment of inertia about the internuclear axis is vanishingly small with respect to other moments of inertia in the molecule (this is due to the very small rotational moments of single atoms, due to the concentration of almost all their mass at their centers; compare also the extremely small radii of the atomic nuclei compared to the distance between them in a diatomic molecule). Quantum mechanically, it can be shown that the interval between successive rotational energy eigenstates is inversely proportional to the moment of inertia about that axis. Because the moment of inertia about the internuclear axis is vanishingly small relative to the other two rotational axes, the energy spacing can be considered so high that no excitations of the rotational state can occur unless the temperature is extremely high. It is easy to calculate the expected number of vibrational degrees of freedom (or vibrational modes). There are three degrees of translational freedom and two degrees of rotational freedom, therefore

- fvib=f−ftrans−frot=6−3−2=1.{displaystyle f_{text{vib}}=f-f_{text{trans}}-f_{text{rot}}=6-3-2=1.}

Each rotational and translational degree of freedom will contribute R/2 in the total molar heat capacity of the gas. Each vibrational mode will contribute R{displaystyle R}

- CV,m=3R2+R+R=7R2=3.5R,{displaystyle C_{V,m}={frac {3R}{2}}+R+R={frac {7R}{2}}=3.5R,}

where the terms originate from the translational, rotational, and vibrational degrees of freedom respectively.

Constant-volume specific heat capacity of diatomic gases (real gases) between about 200 K and 2000 K. This temperature range is not large enough to include both quantum transitions in all gases. Instead, at 200 K, all but hydrogen are fully rotationally excited, so all have at least 5/2 R heat capacity. (Hydrogen is already below 5/2, but it will require cryogenic conditions for even H2 to fall to 3/2 R). Further, only the heavier gases fully reach 7/2 R at the highest temperature, due to the relatively small vibrational energy spacing of these molecules. HCl and H2 begin to make the transition above 500 K, but have not achieved it by 1000 K, since their vibrational energy level spacing is too wide to fully participate in heat capacity, even at this temperature.

The following is a table of some molar constant-volume heat capacities of various diatomic gases at standard temperature (25 °C = 298 K)

| Diatomic gas | CV, m (J/(mol⋅K)) | CV, m/R |

|---|---|---|

| H2 | 20.18 | 2.427 |

| CO | 20.2 | 2.43 |

| N2 | 19.9 | 2.39 |

| Cl2 | 24.1 | 3.06 |

| Br2 (vapour) | 28.2 | 3.39 |

From the above table, clearly there is a problem with the above theory. All of the diatomics examined have heat capacities that are lower than those predicted by the equipartition theorem, except Br2. However, as the atoms composing the molecules become heavier, the heat capacities move closer to their expected values. One of the reasons for this phenomenon is the quantization of vibrational, and to a lesser extent, rotational states. In fact, if it is assumed that the molecules remain in their lowest-energy vibrational state because the inter-level energy spacings for vibration energies are large, the predicted molar constant-volume heat capacity for a diatomic molecule becomes just that from the contributions of translation and rotation:

- CV,m=3R2+R=5R2=2.5R,{displaystyle C_{V,m}={frac {3R}{2}}+R={frac {5R}{2}}=2.5R,}

which is a fairly close approximation of the heat capacities of the lighter molecules in the above table. If the quantum harmonic oscillator approximation is made, it turns out that the quantum vibrational energy level spacings are actually inversely proportional to the square root of the reduced mass of the atoms composing the diatomic molecule. Therefore, in the case of the heavier diatomic molecules such as chlorine or bromine, the quantum vibrational energy-level spacings become finer, which allows more excitations into higher vibrational levels at lower temperatures. This limit for storing heat capacity in vibrational modes, as discussed above, becomes 7R/2 = 3.5 R per mole of gas molecules, which is fairly consistent with the measured value for Br2 at room temperature. As temperatures rise, all diatomic gases approach this value.

General gas phase

The specific heat of the gas is best conceptualized in terms of the degrees of freedom of an individual molecule. The different degrees of freedom correspond to the different ways in which the molecule may store energy. The molecule may store energy in its translational motion according to the formula:

- E=12m(vx2+vy2+vz2){displaystyle E={frac {1}{2}},mleft(v_{x}^{2}+v_{y}^{2}+v_{z}^{2}right)}

where m is the mass of the molecule and [vx,vy,vz]{displaystyle [v_{x},v_{y},v_{z}]}![[v_x,v_y,v_z]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/61a890598143c1f2deb07aa3133a853eb24afcc7)

In addition, a molecule may have rotational motion. The kinetic energy of rotational motion is generally expressed as

- E=12(I1ω12+I2ω22+I3ω32){displaystyle E={frac {1}{2}},left(I_{1}omega _{1}^{2}+I_{2}omega _{2}^{2}+I_{3}omega _{3}^{2}right)}

where I is the moment of inertia tensor of the molecule, and [ω1,ω2,ω3]{displaystyle [omega _{1},omega _{2},omega _{3}]}![[omega_1,omega_2,omega_3]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/503be3f5e3d2e1b0c7ef311075105c640b340173)

The motions of the atoms in a molecule which are not part of its gross translational motion or rotation may be classified as vibrational motions. It can be shown that if there are n atoms in the molecule, there will be as many as v=3n−3−nr{displaystyle v=3n-3-n_{r}}

For example, triatomic nitrous oxide N2O will have only 2 degrees of rotational freedom (since it is a linear molecule) and contains n=3 atoms: thus the number of possible vibrational degrees of freedom will be v = (3⋅3) − 3 − 2 = 4. There are four ways or "modes" in which the three atoms can vibrate, corresponding to 1) A mode in which an atom at each end of the molecule moves away from, or towards, the center atom at the same time, 2) a mode in which either end atom moves asynchronously with regard to the other two, and 3) and 4) two modes in which the molecule bends out of line, from the center, in the two possible planar directions that are orthogonal to its axis. Each vibrational degree of freedom confers TWO total degrees of freedom, since vibrational energy mode partitions into 1 kinetic and 1 potential mode. This would give nitrous oxide 3 translational, 2 rotational, and 4 vibrational modes (but these last giving 8 vibrational degrees of freedom), for storing energy. This is a total of f = 3 + 2 + 8 = 13 total energy-storing degrees of freedom, for N2O.

For a bent molecule like water H2O, a similar calculation gives 9 − 3 − 3 = 3 modes of vibration, and 3 (translational) + 3 (rotational) + 6 (vibrational) = 12 degrees of freedom.

The storage of energy into degrees of freedom

If the molecule could be entirely described using classical mechanics, then the theorem of equipartition of energy could be used to predict that each degree of freedom would have an average energy in the amount of (1/2)kT, where k is Boltzmann's constant, and T is the temperature. Our calculation of the constant-volume heat capacity would be straightforward. Each molecule would be holding, on average, an energy of (f/2)kT, where f is the total number of degrees of freedom in the molecule. Note that Nk = R if N is Avogadro's number, which is the case in considering the heat capacity of a mole of molecules. Thus, the total internal energy of the gas would be (f/2)NkT, where N is the total number of molecules. The heat capacity (at constant volume) would then be a constant (f/2)Nk, the mole-specific heat capacity would be (f/2)R, the molecule-specific heat capacity would be (f/2)k, and the dimensionless heat capacity would be just f/2. Here again, each vibrational degree of freedom contributes 2f. Thus, a mole of nitrous oxide would have a total constant-volume heat capacity (including vibration) of (13/2)R by this calculation.

In summary, the molar heat capacity (mole-specific heat capacity) of an ideal gas with f degrees of freedom is given by

- CV,m=f2R.{displaystyle C_{V,m}={frac {f}{2}}R.}

This equation applies to all polyatomic gases, if the degrees of freedom are known.[26]

The constant-pressure heat capacity for any gas would exceed this by an extra R (see Mayer's relation, above). As example Cp would be a total of (15/2)R for nitrous oxide.

The effect of quantum energy levels in storing energy in degrees of freedom

The various degrees of freedom cannot generally be considered to obey classical mechanics, however. Classically, the energy residing in each degree of freedom is assumed to be continuous—it can take on any positive value, depending on the temperature. In reality, the amount of energy that may reside in a particular degree of freedom is quantized: It may only be increased and decreased in finite amounts. A good estimate of the size of this minimum amount is the energy of the first excited state of that degree of freedom above its ground state. For example, the first vibrational state of the hydrogen chloride (HCl) molecule has an energy of about 5.74 × 10−20 joule. If this amount of energy were deposited in a classical degree of freedom, it would correspond to a temperature of about 4156 K.

If the temperature of the substance is so low that the equipartition energy of (1/2)kT is much smaller than this excitation energy, then there will be little or no energy in this degree of freedom. This degree of freedom is then said to be “frozen out". As mentioned above, the temperature corresponding to the first excited vibrational state of HCl is about 4156 K. For temperatures well below this value, the vibrational degrees of freedom of the HCl molecule will be frozen out. They will contain little energy and will not contribute to the thermal energy or the heat capacity of HCl gas.

Energy storage mode "freeze-out" temperatures

It can be seen that for each degree of freedom there is a critical temperature at which the degree of freedom “unfreezes” and begins to accept energy in a classical way. In the case of translational degrees of freedom, this temperature is that temperature at which the thermal wavelength of the molecules is roughly equal to the size of the container. For a container of macroscopic size (e.g. 10 cm) this temperature is extremely small and has no significance, since the gas will certainly liquify or freeze before this low temperature is reached. For any real gas translational degrees of freedom may be considered to always be classical and contain an average energy of (3/2)kT per molecule.

The rotational degrees of freedom are the next to “unfreeze". In a diatomic gas, for example, the critical temperature for this transition is usually a few tens of kelvins, although with a very light molecule such as hydrogen the rotational energy levels will be spaced so widely that rotational heat capacity may not completely "unfreeze" until considerably higher temperatures are reached. Finally, the vibrational degrees of freedom are generally the last to unfreeze. As an example, for diatomic gases, the critical temperature for the vibrational motion is usually a few thousands of kelvins, and thus for the nitrogen in our example at room temperature, no vibration modes would be excited, and the constant-volume heat capacity at room temperature is (5/2)R/mole, not (7/2)R/mole. As seen above, with some unusually heavy gases such as iodine gas I2, or bromine gas Br2, some vibrational heat capacity may be observed even at room temperatures.

It should be noted that it has been assumed that atoms have no rotational or internal degrees of freedom. This is in fact untrue. For example, atomic electrons can exist in excited states and even the atomic nucleus can have excited states as well. Each of these internal degrees of freedom are assumed to be frozen out due to their relatively high excitation energy. Nevertheless, for sufficiently high temperatures, these degrees of freedom cannot be ignored. In a few exceptional cases, such molecular electronic transitions are of sufficiently low energy that they contribute to heat capacity at room temperature, or even at cryogenic temperatures. One example of an electronic transition degree of freedom which contributes heat capacity at standard temperature is that of nitric oxide (NO), in which the single electron in an anti-bonding molecular orbital has energy transitions which contribute to the heat capacity of the gas even at room temperature.

An example of a nuclear magnetic transition degree of freedom which is of importance to heat capacity, is the transition which converts the spin isomers of hydrogen gas (H2) into each other. At room temperature, the proton spins of hydrogen gas are aligned 75% of the time, resulting in orthohydrogen when they are. Thus, some thermal energy has been stored in the degree of freedom available when parahydrogen (in which spins are anti-aligned) absorbs energy, and is converted to the higher energy ortho form. However, at the temperature of liquid hydrogen, not enough heat energy is available to produce orthohydrogen (that is, the transition energy between forms is large enough to "freeze out" at this low temperature), and thus the parahydrogen form predominates. The heat capacity of the transition is sufficient to release enough heat, as orthohydrogen converts to the lower-energy parahydrogen, to boil the hydrogen liquid to gas again, if this evolved heat is not removed with a catalyst after the gas has been cooled and condensed. This example also illustrates the fact that some modes of storage of heat may not be in constant equilibrium with each other in substances, and heat absorbed or released from such phase changes may "catch up" with temperature changes of substances, only after a certain time. In other words, the heat evolved and absorbed from the ortho-para isomeric transition contributes to the heat capacity of hydrogen on long time-scales, but not on short time-scales. These time scales may also depend on the presence of a catalyst.

Less exotic phase-changes may contribute to the heat-capacity of substances and systems, as well, as (for example) when water is converted back and forth from solid to liquid or gas form. Phase changes store heat energy entirely in breaking the bonds of the potential energy interactions between molecules of a substance. As in the case of hydrogen, it is also possible for phase changes to be hindered as the temperature drops, thus they do not catch up and become apparent, without a catalyst. For example, it is possible to supercool liquid water to below the freezing point, and not observe the heat evolved when the water changes to ice, so long as the water remains liquid. This heat appears instantly when the water freezes.

Solid phase

The dimensionless heat capacity divided by three, as a function of temperature as predicted by the Debye model and by Einstein's earlier model. The horizontal axis is the temperature divided by the Debye temperature. Note that, as expected, the dimensionless heat capacity is zero at absolute zero, and rises to a value of three as the temperature becomes much larger than the Debye temperature. The red line corresponds to the classical limit of the Dulong–Petit law

For matter in a crystalline solid phase, the Dulong–Petit law, which was discovered empirically, states that the molar heat capacity assumes the value 3 R. Indeed, for solid metallic chemical elements at room temperature, molar heat capacities range from about 2.8 R to 3.4 R. Large exceptions at the lower end involve solids composed of relatively low-mass, tightly bonded atoms, such as beryllium at 2.0 R, and diamond at only 0.735 R. The latter conditions create larger quantum vibrational energy spacing, thus many vibrational modes have energies too high to be populated (and thus are "frozen out") at room temperature. At the higher end of possible heat capacities, heat capacity may exceed R by modest amounts, due to contributions from anharmonic vibrations in solids, and sometimes a modest contribution from conduction electrons in metals. These are not degrees of freedom treated in the Einstein or Debye theories.

The theoretical maximum heat capacity for multi-atomic gases at higher temperatures, as the molecules become larger, also approaches the Dulong–Petit limit of 3 R, so long as this is calculated per mole of atoms, not molecules. The reason for this behavior is that, in theory, gases with very large molecules have almost the same high-temperature heat capacity as solids, lacking only the (small) heat capacity contribution that comes from potential energy that cannot be stored between separate molecules in a gas.

The Dulong–Petit limit results from the equipartition theorem, and as such is only valid in the classical limit of a microstate continuum, which is a high temperature limit. For light and non-metallic elements, as well as most of the common molecular solids based on carbon compounds at standard ambient temperature, quantum effects may also play an important role, as they do in multi-atomic gases. These effects usually combine to give heat capacities lower than 3 R per mole of atoms in the solid, although in molecular solids, heat capacities calculated per mole of molecules in molecular solids may be more than 3 R. For example, the heat capacity of water ice at the melting point is about 4.6 R per mole of molecules, but only 1.5 R per mole of atoms. As noted, heat capacity values far lower than 3 R "per atom" (as is the case with diamond and beryllium) result from “freezing out” of possible vibration modes for light atoms at suitably low temperatures, just as happens in many low-mass-atom gases at room temperatures (where vibrational modes are all frozen out). Because of high crystal binding energies, the effects of vibrational mode freezing are observed in solids more often than liquids: for example the heat capacity of liquid water is twice that of ice at near the same temperature, and is again close to the 3 R per mole of atoms of the Dulong–Petit theoretical maximum.

Liquid phase

A general theory of the heat capacity of liquids has not yet been achieved, and is still an active area of research. It was long thought that phonon theory is not able to explain the heat capacity of liquids, since liquids only sustain longitudinal, but not transverse phonons, which in solids are responsible for 2/3 of the heat capacity. However, Brillouin scattering experiments with neutrons and with X-rays, confirming an intuition of Yakov Frenkel,[27] have shown that transverse phonons do exist in liquids, albeit restricted to frequencies above a threshold called the Frenkel frequency. Since most energy is contained in these high-frequency modes, a simple modification of the Debye model is sufficient to yield a good approximation to experimental heat capacities of simple liquids.[28]

Amorphous materials can be considered a type of liquid at temperatures above the glass transition temperature. Below the glass transition temperature amorphous materials are in the solid (glassy) state form. The specific heat has characteristic discontinuities at the glass transition temperature which are caused by the absence in the glassy state of percolating clusters made of broken bonds (configurons) that are present only in the liquid phase.[29] Above the glass transition temperature percolating clusters formed by broken bonds enable a more floppy structure and hence a larger degree of freedom for atomic motion which results in a higher heat capacity of liquids. Below the glass transition temperature there are no extended clusters of broken bonds and the heat capacity is smaller because the solid-state (glassy) structure of amorphous material is more rigid.

The discontinuities in the heat capacity are typically used to detect the glass transition temperature where a supercooled liquid transforms to a glass.

Table of specific heat capacities

Note that the especially high molar values, as for paraffin, gasoline, water and ammonia, result from calculating specific heats in terms of moles of molecules. If specific heat is expressed per mole of atoms for these substances, none of the constant-volume values exceed, to any large extent, the theoretical Dulong–Petit limit of 25 J⋅mol−1⋅K−1 = 3 R per mole of atoms (see the last column of this table). Paraffin, for example, has very large molecules and thus a high heat capacity per mole, but as a substance it does not have remarkable heat capacity in terms of volume, mass, or atom-mol (which is just 1.41 R per mole of atoms, or less than half of most solids, in terms of heat capacity per atom).

In the last column, major departures of solids at standard temperatures from the Dulong–Petit law value of 3 R, are usually due to low atomic weight plus high bond strength (as in diamond) causing some vibration modes to have too much energy to be available to store thermal energy at the measured temperature. For gases, departure from 3 R per mole of atoms in this table is generally due to two factors: (1) failure of the higher quantum-energy-spaced vibration modes in gas molecules to be excited at room temperature, and (2) loss of potential energy degree of freedom for small gas molecules, simply because most of their atoms are not bonded maximally in space to other atoms, as happens in many solids.

| Substance | Phase | Isobaric mass heat capacity cP J⋅g−1⋅K−1 | Isobaric molar heat capacity CP,m J⋅mol−1⋅K−1 | Isochore molar heat capacity CV,m J⋅mol−1⋅K−1 | Isobaric volumetric heat capacity CP,v J⋅cm−3⋅K−1 | Isochore atom-molar heat capacity in units of R CV,am atom-mol−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Air (Sea level, dry, 0 °C (273.15 K)) | gas | 1.0035 | 29.07 | 20.7643 | 0.001297 | ~ 1.25 R |

| Air (typical room conditionsA) | gas | 1.012 | 29.19 | 20.85 | 0.00121 | ~ 1.25 R |

| Aluminium | solid | 0.897 | 24.2 | 2.422 | 2.91 R | |

| Ammonia | liquid | 4.700 | 80.08 | 3.263 | 3.21 R | |

Animal tissue (incl. human)[30] | mixed | 3.5 | 3.7* | |||

| Antimony | solid | 0.207 | 25.2 | 1.386 | 3.03 R | |

| Argon | gas | 0.5203 | 20.7862 | 12.4717 | 1.50 R | |

| Arsenic | solid | 0.328 | 24.6 | 1.878 | 2.96 R | |

| Beryllium | solid | 1.82 | 16.4 | 3.367 | 1.97 R | |

Bismuth[31] | solid | 0.123 | 25.7 | 1.20 | 3.09 R | |

| Cadmium | solid | 0.231 | 26.02 | 3.13 R | ||

Carbon dioxide CO2[26] | gas | 0.839* | 36.94 | 28.46 | 1.14 R | |

| Chromium | solid | 0.449 | 23.35 | 2.81 R | ||

| Copper | solid | 0.385 | 24.47 | 3.45 | 2.94 R | |

| Diamond | solid | 0.5091 | 6.115 | 1.782 | 0.74 R | |

| Ethanol | liquid | 2.44 | 112 | 1.925 | 1.50 R | |

Gasoline (octane) | liquid | 2.22 | 228 | 1.64 | 1.05 R | |

Glass[31] | solid | 0.84 | 2.1 | |||

| Gold | solid | 0.129 | 25.42 | 2.492 | 3.05 R | |

Granite[31] | solid | 0.790 | 2.17 | |||

| Graphite | solid | 0.710 | 8.53 | 1.534 | 1.03 R | |

| Helium | gas | 5.1932 | 20.7862 | 12.4717 | 1.50 R | |

| Hydrogen | gas | 14.30 | 28.82 | 1.23 R | ||

Hydrogen sulfide H2S[26] | gas | 1.015* | 34.60 | 1.05 R | ||

| Iron | solid | 0.412 | 25.09[32] | 3.537 | 3.02 R | |

| Lead | solid | 0.129 | 26.4 | 1.44 | 3.18 R | |

| Lithium | solid | 3.58 | 24.8 | 1.912 | 2.98 R | |

Lithium at 181 °C[33] | liquid | 4.379 | 30.33 | 2.242 | 3.65 R | |

| Magnesium | solid | 1.02 | 24.9 | 1.773 | 2.99 R | |

| Mercury | liquid | 0.1395 | 27.98 | 1.888 | 3.36 R | |

Methane at 2 °C | gas | 2.191 | 35.69 | 0.85 R | ||

Methanol[34] | liquid | 2.14 | 68.62 | 1.38 R | ||

Molten salt (142–540 °C)[35] | liquid | 1.56 | 2.62 | |||

| Nitrogen | gas | 1.040 | 29.12 | 20.8 | 1.25 R | |

| Neon | gas | 1.0301 | 20.7862 | 12.4717 | 1.50 R | |

| Oxygen | gas | 0.918 | 29.38 | 21.0 | 1.26 R | |

Paraffin wax C25H52 | solid | 2.5 (ave) | 900 | 2.325 | 1.41 R | |

Polyethylene (rotomolding grade)[36][37] | solid | 2.3027 | ||||

Silica (fused) | solid | 0.703 | 42.2 | 1.547 | 1.69 R | |

Silver[31] | solid | 0.233 | 24.9 | 2.44 | 2.99 R | |

| Sodium | solid | 1.230 | 28.23 | 3.39 R | ||

| Steel | solid | 0.466 | 3.756 | |||

| Tin | solid | 0.227 | 27.112 | 1.659 | 3.26 R | |

| Titanium | solid | 0.523 | 26.060 | 2.6384 | 3.13 R | |

Tungsten[31] | solid | 0.134 | 24.8 | 2.58 | 2.98 R | |

| Uranium | solid | 0.116 | 27.7 | 2.216 | 3.33 R | |

Water at 100 °C (steam) | gas | 2.080 | 37.47 | 28.03 | 1.12 R | |

Water at 25 °C | liquid | 4.1813 | 75.327 | 74.53 | 4.1796 | 3.02 R |

Water at 100 °C | liquid | 4.1813 | 75.327 | 74.53 | 4.2160 | 3.02 R |

Water at −10 °C (ice)[31] | solid | 2.05 | 38.09 | 1.938 | 1.53 R | |

Zinc[31] | solid | 0.387 | 25.2 | 2.76 | 3.03 R | |

| Substance | Phase | Isobaric mass heat capacity cP J⋅g−1⋅K−1 | Isobaric molar heat capacity CP,m J⋅mol−1⋅K−1 | Isochore molar heat capacity CV,m J⋅mol−1⋅K−1 | Isobaric volumetric heat capacity CP,v J⋅cm−3⋅K−1 | Isochore atom-molar heat capacity in units of R CV,am atom-mol−1 |

A Assuming an altitude of 194 metres above mean sea level (the world–wide median altitude of human habitation), an indoor temperature of 23 °C, a dewpoint of 9 °C (40.85% relative humidity), and 760 mm–Hg sea level–corrected barometric pressure (molar water vapor content = 1.16%).

*Derived data by calculation. This is for water-rich tissues such as brain. The whole-body average figure for mammals is approximately 2.9 J⋅cm−3⋅K−1

[38]

Mass heat capacity of building materials

(Usually of interest to builders and solar designers)

| Substance | Phase | cP J⋅g−1⋅K−1 |

|---|---|---|

| Asphalt | solid | 0.920 |

| Brick | solid | 0.840 |

| Concrete | solid | 0.880 |

Glass, silica | solid | 0.840 |

Glass, crown | solid | 0.670 |

Glass, flint | solid | 0.503 |

Glass, pyrex | solid | 0.753 |

| Granite | solid | 0.790 |

| Gypsum | solid | 1.090 |

Marble, mica | solid | 0.880 |

| Sand | solid | 0.835 |

| Soil | solid | 0.800 |

| Water | liquid | 4.1813 |

| Wood | solid | 1.7 (1.2 to 2.9) |

| Substance | Phase | cP J g−1 K−1 |

See also

- Quantum statistical mechanics

- Heat capacity ratio

- Statistical mechanics

- Thermodynamic equations

- Thermodynamic databases for pure substances

- Heat equation

- Heat transfer coefficient

- Heat of mixing

- Latent heat

- Material properties (thermodynamics)

Joback method (Estimation of heat capacities)

Specific heat of melting (Enthalpy of fusion)

Specific heat of vaporization (Enthalpy of vaporization)- Volumetric heat capacity

- Thermal mass

- R-value (insulation)

- Storage heater

- Frenkel line

Notes

^ ab IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "Standard Pressure". doi:10.1351/goldbook.S05921. Besides being a round number, this had a very practical effect: relatively few[quantify] people live and work at precisely sea level; 100 kPa equates to the mean pressure at an altitude of about 112 metres (which is closer to the 194–metre, world–wide median altitude of human habitation[citation needed]).

References

^ Halliday, David; Resnick, Robert (2013). Fundamentals of Physics. Wiley. p. 524..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Kittel, Charles (2005). Introduction to Solid State Physics (8th ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey, USA: John Wiley & Sons. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-471-41526-8.

^ Blundell, Stephen (2001). Magnetism in Condensed Matter. Oxford Master Series in Condensed Matter Physics (1st ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey, USA: Oxford University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-19-850591-4.

^ Kittel, Charles (2005). Introduction to Solid State Physics (8th ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey, USA: John Wiley & Sons. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-471-41526-8.

^ Laider, Keith J. (1993). The World of Physical Chemistry. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-855919-1.

^ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, Physical Chemistry Division. "Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry" (PDF). Blackwell Sciences. p. 7.The adjective specific before the name of an extensive quantity is often used to mean divided by mass.

^ International Bureau of Weights and Measures (2006), The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (8th ed.), ISBN 92-822-2213-6, archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-14

^ Lange's Handbook of Chemistry, 10th ed. page 1524

^ "Water – Thermal Properties". Engineeringtoolbox.com. Retrieved 2013-10-31.

^ Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach by Yunus A. Cengal and Michael A. Boles.

^ Yunus A. Cengel and Michael A. Boles,Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach, 7th Edition, McGraw-Hill, 2010,

ISBN 007-352932-X.

^ Fraundorf, P. (2003). "Heat capacity in bits". American Journal of Physics. 71 (11): 1142. arXiv:cond-mat/9711074. Bibcode:2003AmJPh..71.1142F. doi:10.1119/1.1593658.

^ D. Lynden-Bell; R. M. Lynden-Bell (Nov 1977). "On the negative specific heat paradox". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 181 (3): 405–419. Bibcode:1977MNRAS.181..405L. doi:10.1093/mnras/181.3.405.

^ Lynden-Bell, D. (Dec 1998). "Negative Specific Heat in Astronomy, Physics and Chemistry". Physica A. 263 (1–4): 293–304. arXiv:cond-mat/9812172v1. Bibcode:1999PhyA..263..293L. doi:10.1016/S0378-4371(98)00518-4.

^ Schmidt, Martin; Kusche, Robert; Hippler, Thomas; Donges, Jörn; Kronmüller, Werner; Issendorff, von, Bernd; Haberland, Hellmut (2001). "Negative Heat Capacity for a Cluster of 147 Sodium Atoms". Physical Review Letters. 86 (7): 1191–4. Bibcode:2001PhRvL..86.1191S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.1191. PMID 11178041.

^ See e.g., Wallace, David (2010). "Gravity, entropy, and cosmology: in search of clarity" (preprint). British Journal for the Philosophy of Science. 61 (3): 513. arXiv:0907.0659. Bibcode:2010BJPS...61..513W. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.314.5655. doi:10.1093/bjps/axp048. Section 4 and onwards.

^ Reif, F. (1965). Fundamentals of statistical and thermal physics. McGraw-Hill. pp. 253–254.

^ Charles Kittel; Herbert Kroemer (2000). Thermal physics. Freeman. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-7167-1088-2.

^ Media:Translational motion.gif

^ Smith, C. G. (2008). Quantum Physics and the Physics of large systems, Part 1A Physics. University of Cambridge.

^ The comparison must be made under constant-volume conditions—CvH— thus no work is performed. Nitrogen’s CvH (100 kPa, 20 °C) = 20.8 J mol−1 K−1 vs. the monatomic gases which equal 12.4717 J mol−1 K−1. Citations: Freeman’s, W. H. "Physical Chemistry Part 3: Change Exercise 21.20b, Pg. 787" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-27.

^ Georgia State University. "Molar Specific Heats of Gases".

^ Petit A.-T., Dulong P.-L. (1819). "Recherches sur quelques points importants de la Théorie de la Chaleur". Annales de Chimie et de Physique. 10: 395–413.

^ "The Heat Capacity of a Solid" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-11.

^ Hogan, C. (1969). "Density of States of an Insulating Ferromagnetic Alloy". Physical Review. 188 (2): 870. Bibcode:1969PhRv..188..870H. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.188.870.