Residue theorem

| Mathematical analysis → Complex analysis |

| Complex analysis |

|---|

|

Complex numbers |

|

Complex functions |

|

Basic Theory |

|

Geometric function theory |

People |

|

|

In complex analysis, a discipline within mathematics, the residue theorem, sometimes called Cauchy's residue theorem, is a powerful tool to evaluate line integrals of analytic functions over closed curves; it can often be used to compute real integrals and infinite series as well. It generalizes the Cauchy integral theorem and Cauchy's integral formula. From a geometrical perspective, it is a special case of the generalized Stokes' theorem.

Contents

1 Statement

2 Examples

2.1 An integral along the real axis

2.2 An infinite sum

3 See also

4 References

5 External links

Statement

The statement is as follows:

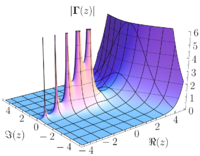

Illustration of the setting.

Let U be a simply connected open subset of the complex plane containing a finite list of points a1, ..., an, and f a function defined and holomorphic on U {a1, ..., an}. Let γ be a closed rectifiable curve in U which does not meet any of the ak, and denote the winding number of γ around ak by I(γ, ak). The line integral of f around γ is equal to 2πi times the sum of residues of f at the points, each counted as many times as γ winds around the point:

- ∮γf(z)dz=2πi∑k=1nI(γ,ak)Res(f,ak).{displaystyle oint _{gamma }f(z),dz=2pi isum _{k=1}^{n}operatorname {I} (gamma ,a_{k})operatorname {Res} (f,a_{k}).}

If γ is a positively oriented simple closed curve, I(γ, ak) = 1 if ak is in the interior of γ, and 0 if not, so

- ∮γf(z)dz=2πi∑Res(f,ak){displaystyle oint _{gamma }f(z),dz=2pi isum operatorname {Res} (f,a_{k})}

with the sum over those ak inside γ.

The relationship of the residue theorem to Stokes' theorem is given by the Jordan curve theorem. The general plane curve γ must first be reduced to a set of simple closed curves {γi} whose total is equivalent to γ for integration purposes; this reduces the problem to finding the integral of f dz along a Jordan curve γi with interior V. The requirement that f be holomorphic on U0 = U {ak} is equivalent to the statement that the exterior derivative d(f dz) = 0 on U0. Thus if two planar regions V and W of U enclose the same subset {aj} of {ak}, the regions V W and W V lie entirely in U0, and hence

- ∫V∖Wd(fdz)−∫W∖Vd(fdz){displaystyle int _{Vsmallsetminus W}d(f,dz)-int _{Wsmallsetminus V}d(f,dz)}

is well-defined and equal to zero. Consequently, the contour integral of f dz along γj = ∂V is equal to the sum of a set of integrals along paths λj, each enclosing an arbitrarily small region around a single aj — the residues of f (up to the conventional factor 2πi) at {aj}. Summing over {γj}, we recover the final expression of the contour integral in terms of the winding numbers {I(γ, ak)}.

In order to evaluate real integrals, the residue theorem is used in the following manner: the integrand is extended to the complex plane and its residues are computed (which is usually easy), and a part of the real axis is extended to a closed curve by attaching a half-circle in the upper or lower half-plane, forming a semicircle. The integral over this curve can then be computed using the residue theorem. Often, the half-circle part of the integral will tend towards zero as the radius of the half-circle grows, leaving only the real-axis part of the integral, the one we were originally interested in.

Examples

An integral along the real axis

The integral

- ∫−∞∞eitxx2+1dx{displaystyle int _{-infty }^{infty }{frac {e^{itx}}{x^{2}+1}},dx}

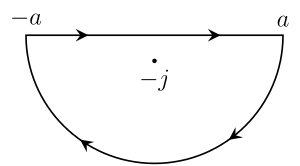

The contour C.

arises in probability theory when calculating the characteristic function of the Cauchy distribution. It resists the techniques of elementary calculus but can be evaluated by expressing it as a limit of contour integrals.

Suppose t > 0 and define the contour C that goes along the real line from −a to a and then counterclockwise along a semicircle centered at 0 from a to −a. Take a to be greater than 1, so that the imaginary unit i is enclosed within the curve. Now consider the contour integral

- ∫Cf(z)dz=∫Ceitzz2+1dz.{displaystyle int _{C}{f(z)},dz=int _{C}{frac {e^{itz}}{z^{2}+1}},dz.}

Since eitz is an entire function (having no singularities at any point in the complex plane), this function has singularities only where the denominator z2 + 1 is zero. Since z2 + 1 = (z + i)(z − i), that happens only where z = i or z = −i. Only one of those points is in the region bounded by this contour. Because f(z) is

- eitzz2+1=eitz2i(1z−i−1z+i)=eitz2i(z−i)−eitz2i(z+i),{displaystyle {begin{aligned}{frac {e^{itz}}{z^{2}+1}}&={frac {e^{itz}}{2i}}left({frac {1}{z-i}}-{frac {1}{z+i}}right)\&={frac {e^{itz}}{2i(z-i)}}-{frac {e^{itz}}{2i(z+i)}},end{aligned}}}

the residue of f(z) at z = i is

- Resz=if(z)=e−t2i.{displaystyle operatorname {Res} limits _{z=i}f(z)={frac {e^{-t}}{2i}}.}

According to the residue theorem, then, we have

- ∫Cf(z)dz=2πi⋅Resz=if(z)=2πie−t2i=πe−t.{displaystyle int _{C}f(z),dz=2pi icdot operatorname {Res} limits _{z=i}f(z)=2pi i{frac {e^{-t}}{2i}}=pi e^{-t}.}

The contour C may be split into a straight part and a curved arc, so that

- ∫straightf(z)dz+∫arcf(z)dz=πe−t{displaystyle int _{mathrm {straight} }f(z),dz+int _{mathrm {arc} }f(z),dz=pi e^{-t},}

and thus

- ∫−aaf(z)dz=πe−t−∫arcf(z)dz.{displaystyle int _{-a}^{a}f(z),dz=pi e^{-t}-int _{mathrm {arc} }f(z),dz.}

Using some estimations, we have

- |∫arceitzz2+1dz|≤πa⋅suparc|eitzz2+1|≤πa⋅suparc1|z2+1|≤πaa2−1,{displaystyle left|int _{mathrm {arc} }{frac {e^{itz}}{z^{2}+1}},dzright|leq pi acdot sup _{text{arc}}left|{frac {e^{itz}}{z^{2}+1}}right|leq pi acdot sup _{text{arc}}{frac {1}{|z^{2}+1|}}leq {frac {pi a}{a^{2}-1}},}

and

- lima→∞πaa2−1=0.{displaystyle lim _{ato infty }{frac {pi a}{a^{2}-1}}=0.}

The estimate on the numerator follows since t > 0, and for complex numbers z along the arc (which lies in the upper halfplane), the argument φ of z lies between 0 and π. So,

- |eitz|=|eit|z|(cosϕ+isinϕ)|=|e−t|z|sinϕ+it|z|cosϕ|=e−t|z|sinϕ≤1.{displaystyle left|e^{itz}right|=left|e^{it|z|(cos phi +isin phi )}right|=left|e^{-t|z|sin phi +it|z|cos phi }right|=e^{-t|z|sin phi }leq 1.}

Therefore,

- ∫−∞∞eitzz2+1dz=πe−t.{displaystyle int _{-infty }^{infty }{frac {e^{itz}}{z^{2}+1}},dz=pi e^{-t}.}

If t < 0 then a similar argument with an arc C′ that winds around −i rather than i shows that

The contour C′.

- ∫−∞∞eitzz2+1dz=πet,{displaystyle int _{-infty }^{infty }{frac {e^{itz}}{z^{2}+1}},dz=pi e^{t},}

and finally we have

- ∫−∞∞eitzz2+1dz=πe−|t|.{displaystyle int _{-infty }^{infty }{frac {e^{itz}}{z^{2}+1}},dz=pi e^{-left|tright|}.}

(If t = 0 then the integral yields immediately to elementary calculus methods and its value is π.)

An infinite sum

The fact that π cot(πz) has simple poles with residue 1 at each integer can be used to compute the sum

- ∑n=−∞∞f(n).{displaystyle displaystyle sum _{n=-infty }^{infty }f(n).}

Consider, for example, f(z) = z−2. Let ΓN be the rectangle that is the boundary of [−N − 1/2, N + 1/2]2 with positive orientation, with an integer N. By the residue formula,

- 12πi∫ΓNf(z)πcot(πz)dz=Resz=0+∑n=−Nn≠0Nn−2.{displaystyle {frac {1}{2pi i}}int _{Gamma _{N}}f(z)pi cot(pi z),dz=operatorname {Res} limits _{z=0}+sum _{n=-N atop nneq 0}^{N}n^{-2}.}

The left-hand side goes to zero as N → ∞ since the integrand has order O(N−2). On the other hand,[1]

- z2cot(z2)=1−B2z22!+⋯;B2=16.{displaystyle {frac {z}{2}}cot left({frac {z}{2}}right)=1-B_{2}{frac {z^{2}}{2!}}+cdots ;qquad B_{2}={frac {1}{6}}.}

(In fact, z/2 cot(z/2) = iz/1 − e−iz − iz/2.) Thus, the residue Resz = 0 is −π2/3. We conclude:

- ∑n=1∞1n2=π26{displaystyle sum _{n=1}^{infty }{frac {1}{n^{2}}}={frac {pi ^{2}}{6}}}

which is a proof of the Basel problem.

The same trick can be used to establish

- πcot(πz)=limN→∞∑n=−NN(z−n)−1,{displaystyle pi cot(pi z)=lim _{Nto infty }sum _{n=-N}^{N}(z-n)^{-1},}

that is, the Eisenstein series.

We take f(z) = (w − z)−1 with w a non-integer and we shall show the above for w. The difficulty in this case is to show the vanishing of the contour integral at infinity. We have:

- ∫ΓNπcot(πz)zdz=0{displaystyle int _{Gamma _{N}}{frac {pi cot(pi z)}{z}},dz=0}

since the integrand is an even function and so the contributions from the contour in the left-half plane and the contour in the right cancel each other out. Thus,

- ∫ΓNf(z)πcot(πz)dz=∫ΓN(1w−z+1z)πcot(πz)dz{displaystyle int _{Gamma _{N}}f(z)pi cot(pi z),dz=int _{Gamma _{N}}left({frac {1}{w-z}}+{frac {1}{z}}right)pi cot(pi z),dz}

goes to zero as N → ∞.

See also

- Cauchy's integral formula

- Glasser's master theorem

- Jordan's lemma

- Methods of contour integration

- Morera's theorem

- Nachbin's theorem

- Residue at infinity

- Logarithmic form

References

^ Whittaker, E. T.; Watson, G. N. (1902). A Course of Modern Analysis. Cambridge University Press. § 7.2..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Ahlfors, Lars (1979), Complex Analysis, McGraw Hill, ISBN 0-07-085008-9

Mitronivić, Dragoslav; Kečkić, Jovan (1984), The Cauchy method of residues: Theory and applications, D. Reidel Publishing Company, ISBN 90-277-1623-4

Lindelöf, Ernst (1905), Le calcul des résidus et ses applications à la théorie des fonctions, Editions Jacques Gabay (published 1989), ISBN 2-87647-060-8

External links

Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001) [1994], "Cauchy integral theorem", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

Residue theorem in MathWorld

Comments

Post a Comment