Doune Castle

| Doune Castle | |

|---|---|

| Doune, Stirling, Scotland UK grid reference NN727010 | |

Aerial view of Doune Castle and the Castle keeper's cottage | |

Doune Castle | |

| Coordinates | 56°11′07″N 4°03′01″W / 56.185158°N 4.050253°W / 56.185158; -4.050253Coordinates: 56°11′07″N 4°03′01″W / 56.185158°N 4.050253°W / 56.185158; -4.050253 |

| Type | Tower house and courtyard |

| Height | 29 metres (95 ft) to top of Lord's tower |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Historic Environment Scotland |

| Controlled by | Duke of Albany (until 1420) King of Scotland (until late 16th century) Earl of Moray |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Site history | |

| Built | c. 1400 |

| Built by | Robert Stewart, Duke of Albany |

| Materials | Stone (coursed rubble with dressed quoins) |

Doune Castle is a medieval stronghold near the village of Doune, in the Stirling district of central Scotland. The castle is sited on a wooded bend where the Ardoch Burn flows into the River Teith. It lies 8 miles (13 km) north-west of Stirling, where the Teith flows into the River Forth. Upstream, 8 miles (13 km) further north-west, the town of Callander lies at the edge of the Trossachs, on the fringe of the Scottish Highlands.

Recent research has shown that Doune Castle was originally built in the thirteenth century, then probably damaged in the Scottish Wars of Independence,[1] before being rebuilt in its present form in the late 14th century by Robert Stewart, Duke of Albany (c. 1340–1420), the son of King Robert II of Scots, and Regent of Scotland from 1388 until his death. Duke Robert's stronghold has survived relatively unchanged and complete, and the whole castle was traditionally thought of as the result of a single period of construction at this time.[2] The castle passed to the crown in 1425, when Albany's son was executed, and was used as a royal hunting lodge and dower house. In the later 16th century, Doune became the property of the Earls of Moray. The castle saw military action during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms and Glencairn's rising in the mid-17th century, and during the Jacobite risings of the late 17th century and 18th century. By 1800 the castle was ruined, but restoration works were carried out in the 1880s, prior to its passing into state care in the 20th century. It is now maintained by Historic Environment Scotland.

Due to the status of its builder, Doune reflected current ideas of what a royal castle building should be.[3] It was planned as a courtyard with ranges of buildings on each side, although only the northern and north-western buildings were completed.[4] These comprise a large tower house over the entrance, containing the rooms of the Lord and his family, and a separate tower containing the kitchen and guest rooms. The two are linked by the great hall. The stonework is almost all from the late 14th century, with only minor repairs carried out in the 1580s. The restoration of the 1880s replaced the timber roofs and internal floors, as well as interior fittings.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Regent Albany

1.2 Royal retreat

1.3 Prison and garrison

1.4 Ruin and restoration

2 Description

2.1 The Lord's tower

2.2 Great Hall and kitchen tower

2.3 Courtyard and curtain wall

2.4 Interpretation of the layout

3 In fiction and drama

3.1 Monty Python and the Holy Grail

4 References

4.1 Bibliography

5 External links

History

Doune Castle sited above the River Teith

The site at the confluence of the Ardoch Burn and the River Teith had been fortified by the Romans in the 1st century AD, although no remains are visible above ground.[3] Ramparts and ditches to the south of the present castle may be the site of an earlier fortification, as the name Doune, derived from Gaelic dùn, meaning "fort", suggests.[5] The earliest identifiable work in the castle dates from the thirteenth century,[1] but it assumed its present form during one of the most creative and productive periods of Scottish medieval architecture, between 1375 and 1425, when numerous castles were being built and remodelled, including Dirleton and Tantallon in Lothian, and Bothwell in Lanarkshire.[6]

Regent Albany

Seal of Robert Stewart, Duke of Albany and Regent of Scotland

In 1361, Robert Stewart (c. 1340–1420), son of King Robert II (reigned 1371–1390), and brother of King Robert III (reigned 1390–1406), was created Earl of Menteith, and was granted the lands on which Doune Castle now stands. Building may have started any time after this, and the castle was at least partially complete in 1381, when a charter was sealed here.[3] Robert was appointed Regent in 1388 for his elderly father, and continued to hold effective power during the reign of his infirm brother. He was created Duke of Albany in 1398. In 1406, Robert III's successor, James I, was captured by the English, and Albany became Regent once more. After this time, the number of charters issued at Doune suggest that the castle became a favoured residence.[3]

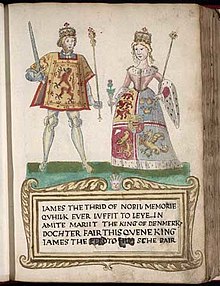

James III and his consort, Margaret of Denmark, who spent part of her widowhood at Doune

Royal retreat

Albany died in 1420, and Doune, the dukedom of Albany, and the Regency all passed to his son Murdoch (1362–1425). The ransom for James I was finally paid to the English, and the King returned in 1424, taking immediate steps to gain control of his kingdom. Albany and two of his sons were imprisoned for treason, and then executed in May 1425. Doune Castle became a royal possession, under an appointed Captain, or Keeper, and served as a retreat and hunting lodge for the Scottish monarchs. It was also used as a dower house by Mary of Guelders (c. 1434–1463), Margaret of Denmark (1456–1486), and Margaret Tudor (1489–1541), the widowed consorts of James II, James III and James IV respectively.[2]

In 1528, Margaret Tudor, now Regent of Scotland for her infant son James V, married Henry Stewart, 1st Lord Methven, a descendant of Albany. His brother, Sir James Stewart (c. 1513–1554), was made Captain of Doune Castle, and Sir James' son, also James (c. 1529–1590), was created Lord Doune in 1570.[2] Lord Doune's son, another James (c. 1565–1592), married Elizabeth Stuart, 2nd Countess of Moray around 1580, becoming Earl of Moray himself. The castle thus came to be the seat of its keepers, the Earls of Moray, who owned it until the 20th century.[2]

Mary, Queen of Scots, (reigned 1542–1567) stayed at Doune on several occasions, occupying the suite of rooms above the kitchen.[7] Doune was held by forces loyal to Mary during the brief civil war which followed her forced abdication in 1567, but the garrison surrendered to the Regent, Matthew Stewart, 4th Earl of Lennox, in 1570, after a three-day blockade.[2]George Buchanan and Duncan Nairn, Deputy Sheriff of Stirling presided over the torture and interrogation of a messenger, John Moon, at Doune on 4 October 1570. Moon was carrying letters to Mary, Queen of Scots and Mary Seton.[8]

King James VI visited Doune on occasion, and in 1581 authorised £300 to be spent on repairs and improvements,[2] the works being carried out by the master mason Michael Ewing[5] under the supervision of Robert Drummond of Carnock, Master of Work to the Crown of Scotland.[9] In 1593, a plot against James was discovered, and the King surprised the conspirators, who included the Earls of Montrose and Gowrie, at Doune Castle.[2]

James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose

Prison and garrison

Photograph of Doune Castle in 1844 by Henry Fox Talbot.

In 1607, the minister, John Munro of Tain, a dissenter against the religious plans of James VI, was imprisoned with a fellow minister at Doune, though he escaped with the contrivance of the then Constable of the Castle, who was subsequently imprisoned for aiding the dissenters. The Royalist James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose occupied Doune Castle in 1645, during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. In 1654, during Glencairn's rising against the occupation of Scotland by Oliver Cromwell, a skirmish took place at Doune between Royalists under Sir Mungo Murray, and Cromwellian troops under Major Tobias Bridge.[2] The castle was garrisoned by government troops during the Jacobite rising of 1689 of Bonnie Dundee, when repairs were ordered, and again during the rising of 1715.[7] During the Jacobite rising of 1745, Doune Castle was occupied by Charles Edward Stuart, "Bonnie Prince Charlie", and his Jacobite Highlanders. It was used as a prison for government troops captured at the Battle of Falkirk. Several prisoners, held in the rooms above the kitchen, escaped by knotting together bedsheets and climbing from the window.[2] Escapees included the author John Home, and a minister, John Witherspoon, who later moved to the American colonies and became a signatory of the United States Declaration of Independence.[10]

Ruin and restoration

Doune Castle – northeast corner

The castle deteriorated through the 18th century, and by 1800 Doune was a roofless ruin. It remained so until the 1880s, when George Stuart, 14th Earl of Moray (1816–1895) began repair works.[2] The timber roofs were replaced, and the interiors, including the panelling in the Lord's Hall, were installed.[5] The castle is now maintained by Historic Environment Scotland, having been donated to a predecessor organisation by Douglas Stuart, 20th Earl of Moray, in 1984, and is open to the public. The castle is a Scheduled Ancient Monument.[11]

Description

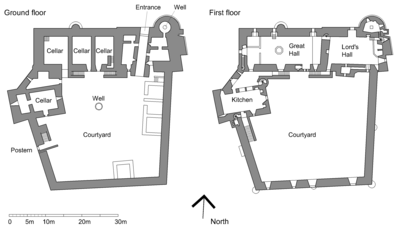

Ground floor and first floor plans of the castle

Doune occupies a strategic site, close to the geographical centre of Scotland, and only 5 miles (8.0 km) from Stirling Castle, the "crossroads of Scotland".[5] The site is naturally defended on three sides by steeply-sloping ground, and by the two rivers to east and west. The castle forms an irregular pentagon in plan, with buildings along the north and north-west sides enclosing a courtyard. It is entered from the north via a passage beneath a tower containing the principal rooms of the castle. From the courtyard, three sets of stone external stairs, which may be later additions,[12] lead up to the Lord's Hall in the tower, to the adjacent Great Hall, and to the kitchens in a second tower to the west.

The main approach, from the north, is defended by earthworks, comprising three ditches, with a rampart, or earthen wall, between. Also outside the castle walls is a vaulted passage, traditionally said to lead into the castle, but in fact accessing an 18th-century ice house.[12] There are no openings within the lower part of the castle's walls, excepting the entrance and the postern, or side gate, to the west, although there are relatively large windows on the upper storeys. Windows in the south wall suggest that further buildings were intended within the courtyard, but were never built. The stonework is of coursed sandstone rubble, with dressings in lighter Ballengeich stone.[5]

The Lord's tower

The principal tower, or gatehouse, is rectangular in plan 18 metres (59 ft) by 13 metres (43 ft), and almost 29 metres (95 ft) high,[2] with a projecting round tower on the north-east corner, beside the entrance. It comprises the Lord's Hall, and three storeys of chambers above, located over the entrance passage. The vaulted, cobbled passage, 14 metres (46 ft) long, was formerly defended by two sets of timber doors, and a yett, or hinged iron grille, remains.[5] Guardrooms on either side overlook the passage via gunloops, and also on the ground floor is a well, in the basement of the round tower.

The restored Lord's Hall

There is no direct communication between the ground floor and the Lord's Hall above, which occupies the whole first floor. This is accessed via an enclosed and gated stair from the courtyard. The hall is vaulted, and has an unusual double fireplace. The floor tiles, timber panelling, and minstrels' gallery are additions of the 1880s. It was originally thought that the connecting door to the Great Hall was also of this date, but is now accepted as being original.[5] Side rooms on the hall level include a chamber in the round tower, with a hatch above the well, and a small chamber within the south wall which overlooks both hall and courtyard. A machicolation, or "murder hole", below the hall's north window, allows objects to be dropped onto attackers in the passage.[5]

Above the hall is a second hall, forming part of the Duchess' suite of rooms. An oratory in the south wall, overlooking the courtyard, contains a piscina and credence niche. The oratory gives access to mural passages leading to the walkway along the curtain wall. The timber ceiling of the Duchess' hall, and the timber floors and roof above, are of the 1880s. The upper parts of the stonework are among the repairs dating from 1580.[5]

Great Hall and kitchen tower

The kitchen tower from the courtyard, with the steps up to the Great Hall to the right of the picture

West of the Lord's tower is the Great Hall, 20 metres (66 ft) by 8 metres (26 ft), and 12 metres (39 ft) high to its timber roof,[2] again a 19th-century replacement.[5] The hall has no fireplace, and was presumably heated by a central fire, and ventilated by means of a louvre like the one in the modern roof. No details of the original roof construction are known, however, and the restoration is conjectural.[3] Large windows light the hall, and stairs lead down to the three cellars on ground level.

The hall is accessed from the courtyard via a stair up to a triangular lobby, which in turn links the hall and kitchens by means of two large serving hatches with elliptical arches, unusual for this period.[13] The kitchen tower, virtually a tower house in its own right, is 17 metres (56 ft) by 8 metres (26 ft). The vaulted kitchen is on the hall level, above a cellar. One of the best-appointed castle kitchens in Scotland of its date,[3] it has an oven and a 5.5-metre (18 ft) wide fireplace. A stair turret, added in 1581 and possibly replacing a timber stair,[5] leads up from the lobby to two storeys of guest rooms. These include the "Royal Apartments", a suite of two bedrooms plus an audience chamber, suitable for royal visitors.[2]

Courtyard and curtain wall

Projecting stones on the south wall of the kitchen block, known as tuskings, and four pointed-arched windows in the south curtain wall, suggest that further ranges of buildings were planned. The large, eastern-most window, may have been intended for a chapel, and it is recorded that a chapel dedicated to the 8th-century monk Saint Fillan was located at Doune Castle, but the lack of foundations suggest that there was no large building in this part of the castle.[5] The foundations which do exist were excavated in September 2002, revealing a structure which was interpreted as a kiln or oven against the south wall.[12] The central well is around 18 metres (59 ft) deep.[2]

The curtain wall is 2 metres (6.6 ft) thick, and 12 metres (39 ft) high.[2] A walkway along the top of the wall is protected by parapets on both sides, and is carried over the pitched roofs of the hall and gatehouse by steep steps. Open, round turrets are located at each corner, with semicircular projections at the midpoint of each wall. A square turret with machicolations is located above the postern gate in the west wall.[5]

The south wall of Doune Castle rising above the river bank

Interpretation of the layout

The Lord's tower is a secure, private set of rooms, probably intended for the sole use of the Lord and his family, and with its own lines of defence. The architectural historian W. Douglas Simpson interpreted this arrangement as being the product of the "bastard feudalism" of the 14th century.[14] During this period, Lords were required to defend their castles by means of mercenaries, rather than the vassals of the earlier feudal system, and Simpson suggested that the Lord of Doune designed his tower to be defensible against his own, potentially rebellious, garrison. This interpretation is no longer widely accepted by historians, and the castle is instead seen as a development towards more integrated courtyard buildings, such as the royal palace of Linlithgow, which was constructed through the 15th and early 16th century.[5] The layout of Doune has similarities with those of the contemporary castles at Tantallon and Bothwell, and appears, at various scales, in other buildings of the period.[1][3]

In fiction and drama

Doune Castle in an 1804 engraving in the publication Scotia Depicta preceding Scott's depiction of the castle in his novel Waverley

Doune Castle has featured in several literary works, including the 17th-century ballad, "The Bonny Earl of Murray", which relates the murder of The 2nd Earl of Moray, by The 6th Earl of Huntly, in 1592.[15] In Sir Walter Scott's first novel, Waverley (1814), the protagonist Edward Waverley is brought to Doune Castle by the Jacobites. Scott's romantic novel describes the "gloomy yet picturesque structure", with its "half-ruined turrets".[16]

The castle was used as a location in MGM's 1952 historical film Ivanhoe which featured Robert Taylor and Elizabeth Taylor.[17] The BBC adaptation of Ivanhoe in 1996 also featured Doune as a location. The castle was used as a set for Winterfell in the first season of the TV series Game of Thrones (2011–present), an adaptation of the A Song of Ice and Fire series of novels by George R. R. Martin.[18]

The castle was used as a stand-in for the fictional "Castle Leoch" in the TV adaptation of the Outlander series of novels.[19]

The castle was also used as a location in Outlaw King [20]. Outlaw King is a 2018 historical action drama film about Robert the Bruce, the 14th-century Scottish King who launched a guerilla war against the larger English army. The film largely takes place during the 3-year historical period from 1304, when Bruce decides to rebel against the rule of Edward I over Scotland, thus becoming an "outlaw", up to the 1307 Battle of Loudoun Hill. Outlaw King was co-written, produced, and directed by David Mackenzie. It stars Chris Pine, Aaron Taylor-Johnson, Florence Pugh, Billy Howle, Tony Curran, Callan Mulvey, Stephen Dillane, and Alan Cooney.

It premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival on September 6, 2018, and was released on November 9, 2018, by Netflix.

[21]

Monty Python and the Holy Grail

The east wall of Doune Castle, where the opening scene of Monty Python and the Holy Grail takes place

The British comedy film Monty Python and the Holy Grail – a parody of the legends of King Arthur by the Monty Python team – was filmed on location in Scotland in 1974. The film's producers had gained permission from the National Trust for Scotland to film scenes at several of their Scottish castles, as well as the permission of Lord Moray to film at Doune Castle. However, the National Trust later withdrew their permission, leaving the producers with little time to find new locations. Instead, they decided to use different parts of Doune Castle to depict the various fictional castles in the film, relying on tight framing of shots to maintain the illusion.

Scenes featuring Doune Castle include:[22]

- At the start of the film, King Arthur (Graham Chapman) and Patsy (Terry Gilliam) approach the east wall of Doune Castle and argue with soldiers of the garrison.

- The song and dance routine "Knights of the Round Table" at "Camelot" was filmed in the Great Hall.

- The servery and kitchen appear as "Castle Anthrax", where Sir Galahad the Chaste (Michael Palin) is chased by seductive girls.

- The wedding disrupted by Sir Lancelot (John Cleese) was filmed in the courtyard and Great Hall.

- The Duchess' hall was used for filming the Swamp Castle scene where the prince is being held in a tower by very dumb guards.

- The Trojan Rabbit scene was filmed in the entryway and into the courtyard.

The only other castles used for filming were Castle Stalker in Argyll, also privately owned, which appears as "Castle Aaaaarrrrrrggghhh" at the end of the film, and (briefly) Kidwelly Castle in Wales and Bodiam Castle in East Sussex. The DVD version of Monty Python and the Holy Grail includes a documentary, In Search of the Holy Grail Filming Locations, in which Michael Palin and Terry Jones revisit Doune and other sites used for filming. Doune Castle has become a place of pilgrimage for fans of Monty Python and the film, it used to hold an annual "Monty Python Day" but it no longer does this.[23]

References

^ abc Oram, pp. 54–55

^ abcdefghijklmno Salter, pp. 82–84

^ abcdefg Fawcett, pp. 7–11

^ Tabraham, pp. 144–45

^ abcdefghijklmn Gifford and Walker, pp. 378–82

^ Fawcett, p. 3

^ ab Coventry, pp. 253–54

^ Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 3 (1903), pp. 384–85: A Diurnal of Remarkable Occurents in Scotland, Bannatyne Club (1833), pp. 185–86

^ Pringle, p. 8: Fraser, William, The Red Book of Menteith, vol. 2 (1880), 419–21, no. 125.

^ "John Witherspoon". The History of the Presbyterian Church. Archived from the original on February 20, 2008. Retrieved 2007-12-30..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Doune Castle (SM12765)". Retrieved 19 February 2019.

^ abc "Doune Castle, NMRS Number: NN70SW 1". CANMORE. RCAHMS. Retrieved 2008-10-17.

^ MacGibbon and Ross, pp. 418–29

^ Simpson, pp. 73–83

^ "The Bonny Earl o' Moray". Retrieved 2008-10-14.

^ Scott, Walter (1814). "Chapter IX: A Nocturnal Adventure". Waverley. Retrieved 2008-10-14.

^ "Visit Scotland: Stage and Screen". Retrieved 2009-01-10.

^ "Medieval keep becomes film set". BBC News. 23 October 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-25.

^ Visit Scotland - Outlander Filming Locations

^ Outlaw King - Netflix

^ Behind the scenes - Historic Scotland

^ "Monty Python and the Holy Grail – Doune Castle". Scotland: the Movie Location Guide. Archived from the original on 2014-12-11. Retrieved 2008-10-24.

^ "Python fans in castle pilgrimage". BBC News. 4 September 2005. Retrieved 2008-10-14.

Bibliography

Fawcett, Richard (1994). Scottish Architecture from the accession of the Stewarts to the Reformation, 1371–1560. Architectural History of Scotland. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-0465-4.

Fraser, William (1880). The Red Book of Menteith. Edinburgh.

Gifford, John; Walker, Frank Arneil (2002). Stirling and Central Scotland. Buildings of Scotland. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09594-5.

MacGibbon, David; Ross, Thomas (1887). The Domestic and Castellated Architecture of Scotland. Vol. I. David Douglas. ISBN 0-901824-18-6.

Oram, Richard (2011). "The Great House in Late Medieval Scotland: Courtyards and Towers c. 1300 – c. 1400"". In Airs, M.; Barnwell, P.S. The Medieval Great House. Rewley House Studies in the Historic Environment. Shaun Tyas. pp. 43–60. ISBN 978-1-907730-07-8.

Pringle, R. Denys (1987). Doune Castle. HMSO.

Salter, Mike (1994). The Castles of the Heartland of Scotland. Folly Publications. ISBN 1-871731-18-6.

Simpson, W. Douglas (1938). "Doune Castle" (PDF). Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 72: 73–83.

Tabraham, Chris (1997). Scotland's Castles. B.T. Batsford/Historic Scotland. ISBN 0-7134-8147-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Doune Castle. |

- Doune Castle – site information from Historic Environment Scotland

Engraving of Doune Castle by James Fittler in the digitised copy of Scotia Depicta, or the antiquities, castles, public buildings, noblemen and gentlemen's seats, cities, towns and picturesque scenery of Scotland (1804) at National Library of Scotland

Comments

Post a Comment