Fortress of Klis

| Klis Fortress Tvrđava Klis | |

|---|---|

| Klis, near Split Croatia | |

Klis Fortress built into the south face of a rocky mass, barely discernible as a man-made structure, seen from the state route D1. | |

Klis Fortress Tvrđava Klis | |

| Coordinates | 43°33′36″N 16°31′25″E / 43.56°N 16.5235°E / 43.56; 16.5235 |

| Type | Fortification, mixed |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | List of rulers 1.) Small stronghold (Gradina)

2.) Royal Castle

3.) Fortress

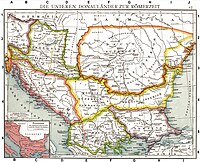

Lands ruled by Louis in the 1370s.

4.) Major strategic value

5.) Lost its main strategic weight

6.) Abandoned as a permanent military outpost

|

| Open to the public | Yes

|

| Condition | Preserved, slightly renovated |

| Site history | |

| Built | Unknown, probably in the 3rd century BC |

| Built by | Small stronghold by Illyrian tribe of Dalmatae, later expanded mostly by:

|

| Materials | Limestone |

The Klis Fortress (Croatian: Tvrđava Klis) is a medieval fortress situated above a village bearing the same name, near Split, Croatia. From its origin as a small stronghold built by the ancient Illyrian tribe Dalmatae, becoming a royal castle that was the seat of many Croatian kings, to its final development as a large fortress during the Ottoman wars in Europe, Klis Fortress has guarded the frontier, being lost and re-conquered several times throughout its more-than-two-thousand-year-long history. Due to its location on a pass that separates the mountains Mosor and Kozjak, the fortress served as a major source of defense in Dalmatia, especially against the Ottoman advance, and has been a key crossroad between the Mediterranean belt and the Balkan rear.

Contents

1 Importance

2 Location

3 History

3.1 Ancient stronghold of Illyrians and Romans

3.2 Migration period and the arrival of the Croats

3.3 Royal Castle

3.4 Knights Templar

3.5 Mongol siege

3.6 Šubić's rule

3.7 Petar Kružić and the Uskoci

3.8 Final Ottoman siege

3.9 Sanjak centre of Ottoman Bosnia

3.10 Venetian domination

4 Architecture

4.1 Fortress outskirts

4.2 Present appearance

4.2.1 First defensive line

4.2.2 Second defensive line

4.2.3 Third defensive line

5 Present day

6 In popular culture

7 Gallery

8 See also

9 Notes

10 References

11 Further reading

12 External links

Importance

Since Duke Mislav of the Duchy of Croatia made Klis Fortress the seat of his throne in the middle of the 9th century, the fortress served as the seat of many Croatia's rulers. The reign of his successor, Duke Trpimir I, the founder of the Croatian royal House of Trpimirović, is significant for spreading Christianity in the Duchy of Croatia. He largely expanded the Klis Fortress, and in Rižinice, in the valley under the fortress, he built a church and the first Benedictine monastery in Croatia. During the reign of the first Croatian king, Tomislav, Klis and Biograd na Moru were his chief residences.

In March 1242 at Klis Fortress, Tatars who were a constituent segment of the Mongol army under the leadership of Kadan suffered a major defeat while in pursuit of the Hungarian army led by King Béla IV. After their defeat by Croatian forces, the Mongols retreated, and Béla IV rewarded many Croatian towns and nobles with "substantial riches". During the Late Middle Ages, the fortress was governed by Croatian nobility, amongst whom Paul I Šubić of Bribir was the most significant. During his reign, the House of Šubić controlled most of modern-day Croatia and Bosnia. Excluding the brief possession by the forces of Bosnian King, Tvrtko I, the fortress remained in Hungaro-Croatian hands for the next several hundred years, until the 16th century.

Klis Fortress is probably best known for its defense against the Ottoman invasion of Europe in the early 16th century. Croatian captain Petar Kružić led the defense of the fortress against a Turkish invasion and siege that lasted for more than two and a half decades. During this defense, as Kružić and his soldiers fought without allies against the Turks, the military faction of Uskoks was formed, which later became famous as an elite Croatian militant sect. Ultimately, the defenders were defeated and the fortress was occupied by the Ottomans in 1537. After more than a century under Ottoman rule, in 1669, Klis Fortress was besieged and seized by the Republic of Venice, thus moving the border between Christian and Muslim Europe further east and helping to contribute to the decline of the Ottoman Empire. The Venetians restored and enlarged the fortress, but it was taken by the Austrians after Napoleon extinguished the republic itself in 1797. Today, Klis Fortress contains a museum where visitors to this historic military structure can see an array of arms, armor, and traditional uniforms.

Location

The fortress is located above a village bearing the same name, 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) from the Adriatic Sea, on a pass that separates the mountains Mosor and Kozjak, at the altitude of 360 metres (1,180 ft), northeast of Split in Croatia.[1] Owing to its strategic position, the fortress is regarded as one of the region's most important fortifications.[2]

Perched on an isolated rocky eminence, inaccessible on three sides, the fortress overlooks Split, the ancient Roman settlement of Salona, Solin, Kaštela and Trogir, and most of the central Dalmatian islands.[2][3] Historically, the fortress has controlled access to and from Bosnia, Dalmatia and inland Croatia.[2] The importance of such a position was felt by every army that invaded, or held possession of this part of Croatia.[3] Klis Fortress was a point against which their attacks were always directed, and it has been remarkable for the many sieges it withstood.[3] It has been of major strategic value in Croatia throughout history.[2]

History

Ancient stronghold of Illyrians and Romans

The ancient Illyrian tribe of Dalmatae, which held a stronghold on this spot, were the first known inhabitants who lived on the site of what is today Klis Fortress.[4] They were defeated several times, and in the year 9 AD, finally annexed by Romans.[4] Today's Klis Fortress was known to the Romans by the name of "Andetrium" or "Anderium",[5] and in later times "Clausura", which is the origin of later "Clissa" and modern "Klis".[3] To the Romans, Klis became famous for its celebrated siege by Augustus, at the time of the Illyrian revolt in Dalmatia.[6] The road that lead from Klis to Salona was called "Via Gabiniana" or "Via Gabinia", which according to an inscription found at Salona, appears to have been made by Tiberius.[3] Southeast of the fortress, the traces of a Roman camp are still visible, as well as an inscription carved on a rock; both which are supposed to be contemporary with the siege under Tiberius.[3] The description of this siege during the Illyrian Wars demonstrates that this place was strong and unreachable in those times.[6]

Migration period and the arrival of the Croats

After the fall of the Roman Empire, Barbarians plundered the region around Klis.[7] First it was ruled by Odoacer, and then by the Theodoric the Great, after he eliminated Odoacer, and set up an Ostrogothic Kingdom.[7] After Justinian I fought an almost continual war for forty years to recover the old Roman Empire, he seized Dalmatia, and Klis was from 537, a part of Byzantine Empire.[7] The name of Klis (Kleisa or Kleisoura) was first described in chapter 29 of Emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus' De Administrando Imperio.[8] While describing the Roman settlement of Salona, Constantine VII speaks of the stronghold, which may have been designed or improved, to prevent attacks on the coastal cities and roads by Slavs.[8]

Salona, the capital of the province of Dalmatia was sacked and destroyed in 614 by Avars and Slavs.[9] The population fled to Diocletian's walled palace of Split, which was able to hold up.[9] Thereafter, Split rose quickly in importance, as one of Dalmatia's major cities.[9] After a few decades, the Avars were driven out by the Croats.[9] This probably happened after 620, when in second wave Croats migrated on the invitation by the Emperor Heraclius to counter the Avar threat on the Byzantine Empire.[10]

Royal Castle

From the early 7th century on, Klis was an important Croat stronghold, and later, one of the seats of many Croatia's rulers.[2] In the 9th century, Croatian duke Mislav of the Duchy of Croatia, from 835 to 845, made the castle of Klis seat of his throne.[1] Despite Frankish overlordship, the Franks had almost no role in Croatia in the period from the 820s through 840s. After Mislav's death, starting with Duke Trpimir I, Klis was ruled by royal members of the House of Trpimirović, who were at first Dukes of the Croatian Duchy (dux Croatorum), and afterwards Kings of the Croatian Kingdom (rex Croatorum). They developed the early Roman stronghold into their capital.[2] Relations with the Byzantines greatly improved under the Croatian duke Trpimir I, who moved the dux's main residence from Nin to Klis.[11]

The reign of Mislav's successor Trpimir I, is significant for spreading Christianity in the medieval Croatian state, and for the first mention of the name "Croats" in domestic documents.[12][13] On 4 March, in 852, Trpimir I issued a "Charter in Biaći" (Latin: in loco Byaci dicitur) in Latin, confirming Mislav's donations to the Archbishopric in Split.[13] In this document Trpimir I named himself; "By the mercy of God, Duke of Croats" (Latin: Dux Chroatorum iuvatus munere divino), and his realm as the "Realm of the Croats" (Latin: Regnum Chroatorum).[13] In the same document Trpimir I mentioned Klis as his property — seat.[12] Under Klis, in Rižinice, the duke Trpimir built a church and the first Benedictine monastery in Croatia, which is known from the discovery of a stone fragment on a gable arch from an altar screen, inscribed with the duke's name and title.[12]

| “ | (Latin ... pro duce Trepimero ... – English... for Duke Trpimir ...) | ” |

Archaeological excavations found that a church dedicated to Saint Vitus was founded in the 10th century by a certain Croatian king, along with his wife, Queen Domaslava, which got destroyed during Ottoman conquests in the 16th century.[14]

A controversial Saxon theologian of the mid-9th century, Gottschalk of Orbais, spent some time at Trpimir's court between 846 and 848.[12] His work "De Trina deitate" is an important source of information for Trpimir's reign.[12] Gottschalk was a witness to the battle between Trpimir and Byzantine strategos, when Trpimir was victorious.[12] During the reign of Croatian king Tomislav, who had no permanent capital, the castle of Klis along with Biograd, were his chief residences.[15]

Knights Templar

From the early 12th century, and after the decay of the native Croatian royal family of Trpimirović, the castle of Klis was mainly governed by Croatian nobility, under the supremacy of Hungarian kings. The Kingdom of Croatia and the Kingdom of Hungary were, from 1102, in a personal union of two kingdoms, united under the Hungarian king.[Note 1][16]

Andrew II of Hungary was extremely favorably disposed towards the Templars.[17] During his participation in the Fifth Crusade, he appointed Pontius de Cruce, Master of the Order in the Hungarian Kingdom, as a regent in Croatia and Dalmatia.[17] After his return in 1219, in recognition of the great logistical and financial support which the Order had given him during the campaign, he granted the Order the estate of Gacka.[17] Even before his departure from the city of Split in 1217, he had made over to the Templars the castle of Klis (Clissa), a strategic point in the hinterland of Split (Spalato), which controlled the approaches to the town.[3][17][18] The king Andrew was reluctant to entrust the castle of Klis to any of the local magnates, knowing what great harm could come from that castle.[18] It was the king's will that Split receive the castle of Klis for the defense of their city.[18] The city of Split showed little interest in the royal favors, so the king entrusted Klis into Templars hands.[18] Shortly after this, the Templars lost Klis, and, in exchange, the king gave them the coastal town of Šibenik (Sebenico).[17]

Mongol siege

Tatars under the leadership of Kadan experienced a major failure in March 1242 at Klis Fortress, when they were hunting for Béla IV of Hungary.[4] The Tatars believed that the king was in the Klis Fortress, and so they began to attack from all sides, launching arrows and hurling spears.[19] However, the natural defenses of the fortress gave protection, and the Tatars could cause only limited harm.[19] They dismounted from their horses and began to creep up hand over hand to higher ground.[19] But the fortress defenders hurled huge stones at them, and managed to kill a great number.[19] This setback only made the Tatars more ferocious, and they came right up to the great walls and fought hand to hand.[19] They looted the houses in the outskirt of the fortress and took away much plunder, but failed to take Klis altogether.[19] Upon learning that the king was not there, they abandoned their attack, and ascending their mounts rode off in the direction of Trogir,[19] a number of them turning off toward Split.[19]

The Mongols attacked the Dalmatian cities for the next few years but eventually withdrew without major success, as the mountainous terrain and distance were not suitable for their style of warfare.[20] They pursued Béla IV from town to town in Dalmatia.[20] The Croatian nobility and Dalmatian towns such as Trogir and Rab helped Béla IV to escape.[20] After this failure, the Mongols retreated and Béla IV rewarded the Croatian towns and nobility.[20] Only the city of Split did not help Béla IV in his escape.[20]

Some historians claim that the mountainous terrain of Croatian Dalmatia was fatal for the Mongols, because they suffered great losses when attacked by the Croats from ambushes in mountain passes.[20] Other historians claim that the death of Ögedei Khan (Croatian: Ogotaj) was the only reason for retreat. Much of Croatia was plundered by the Mongols, but without any major military success.[20]Saint Margaret (January 27, 1242 – January 18, 1271), a daughter of Béla IV and Maria Laskarina, was born in Klis Fortress during the Mongol invasion of Hungary-Croatia.[2]

Šubić's rule

The weakening of royal authority under Stephen V of Hungary allowed the House of Šubić to regain their former role in Dalmatia.[21] In 1274, Stjepko Šubić of Bribir died, and Paul I Šubić of Bribir succeeded him as the family elder.[21] Soon, Ladislaus IV of Hungary, recognizing the balance of power in Dalmatia, named Paul I as Ban of Croatia and Dalmatia.[21] Ladislaus IV died in 1290 leaving no sons, and a civil war between rival candidates, pro-Hungarian Andrew III of Hungary, and pro-Croatian Charles Martel of Anjou, started.[22] Charles Martel's father Charles II of Naples, awarded all Croatia from Gvozd Mountain (Croatian: Petrova Gora) to the river Neretva mouth hereditary to Paul I Šubić of Bribir.[22] Thus, Charles converted Paul's personal position as Ban into a hereditary one for the Šubić family.[22] All the other nobles in this region, were to be vassals of Paul Šubić.[22] In response, Andrew III in 1293 issued a similar charter for Paul Šubić.[22] During this struggle over the throne, George I Šubić of Bribir, Ban Paul's brother went to Italy, visiting the pope and the Naples court.[23] In August 1300, George I returned to Split, bringing Charles Robert with him.[23] Paul Šubić accompanied Charles Robert (later known as Charles I of Hungary) to Zagreb, where he was recognized as king; then they proceeded to Esztergom, where, in 1301, the Archbishop of Esztergom crowned him as King of Hungary and Croatia.[23]

Paul I Šubić, Ban of Croatia and Dalmatia, became Lord of all of Bosnia in 1299.[24] Although supporting the king, Paul I continued to act independently, and ruled over a large portion of modern-day Croatia and Bosnia.[24] He appointed his brothers as commissars of Dalmatian cities, and gave Split to his brother Mladen I Šubić, and Šibenik, Nin, Trogir and Omiš to his brother George I Šubić.[24] After George I Šubić died in 1302, his brother Mladen I Šubić ruled as a Bosnian Ban over Bosnia from Klis Fortress, until he was killed in a battle during 1304.[24] Then, Šubić gave the Klis Fortress to his son Mladen II Šubić, who ruled over Bosnia like his uncle Mladen I.[24]George II Šubić and his son, Mladen III Šubić, ruled over Klis Fortress until the late 14th century.[24] During summer-long festivities in Klis Fortress, open to the whole population, Mladen III Šubić gave his sister's Jelena Šubić hand in marriage to Vladislaus of Bosnia, from the House of Kotromanić.[20] Jelena Šubić gave birth to the first Bosnian King, Tvrtko I, who later inherited the fortress.[4]

Petar Kružić and the Uskoci

Owing to its location, Klis Fortress was an important defensive position during the Ottoman conquest of the Balkans.[25] The fortress stands along the route by which the Ottomans could penetrate the mountain barrier separating the coastal lowlands from around Split, from Turkish-held Bosnia.[25] The Croat feudal lord Petar Kružić gathered together a garrison composed of Croat refugees, who used the base at Klis both to hold the Turks at bay, and to engage in marauding and piracy against coastal shipping.[25] Although nominally accepting the sovereignty of the Habsburg king Ferdinand who had obtained the Croatian crown in 1527,[Note 2] Kružić and his freebooting Uskoks were a law unto themselves.[25]

When a large Turkish force threatened the fortress, Kružić appealed to Ferdinand I for help, but the Emperor's attention was diverted by a Turkish invasion into Slavonia.[25] For more than two and half decades, Captain Kružić, also called (Prince of Klis), defended the fortress against the Turkish invasion.[4] Kružić led the defense of Klis, and with his soldiers fought almost alone against the Ottomans, as they hurled army after army against the fortress.[4] No troops would come from the Hungarian king, as they were defeated by the Ottomans at the Battle of Mohács in 1526, and the Venetians baulked at sending any help.[4] Only the popes were willing to provide some men and money.[4]

Final Ottoman siege

Pope Paul III claimed some rights in Klis, and in September, 1536, there was talk in the Curia of strengthening the defenses of the fortress.[27] The Pope notified Ferdinand that he was willing to share the costs of maintaining a proper garrison in Klis.[27] Ferdinand I did send aid to Klis and was apparently hopeful of holding the fortress, when the Turks again laid siege to it.[27] Ferdinand I recruited men from Trieste and elsewhere in the Habsburg lands, and Pope Paul III sent soldiers from Ancona.[27] There were about 3,000 infantry in the reinforcements, which made a sizeable relief force, that were commanded by Petar Kružić, Niccolo dalla Torre, and a papal commissioner Jacomo Dalmoro d'Arbe.[27] On March 9, 1537, they disembarked near Klis, at a place called S. Girolamo, with fourteen pieces of artillery.[27] After Ibrahim's death, Suleiman the Magnificent sent 8,000 men under the command of Murat-beg Tardić (Amurat Vaivoda), a Croatian renegade who had been born in Šibenik, to go and lay siege to Klis fortress (Clissa), and fight against Petar Kružić.[28] An initial encounter of the Christian relief force with the Turks was indecisive, but, on March 12, they were overwhelmed by the arrival of a great number of Turks.[27]

The attempts to relieve the citadel ended in farce.[29] Badly-drilled reinforcements sent by the Habsburgs fled in the fear of Turks, and their attempts to re-board their boats at Solin bay caused many vessels to sink.[29] Niccolo dalla Torre and the papal commissioner managed to escape.[28] Kružić himself – who had left the fortress to make contact with the reinforcements was captured and executed: the sight of his head on a stick was too much for the remaining defenders of Klis, who were now willing to give up the fortress in return for safe passage north.[29] After Petar Kružić's death, and with a lack of water supplies, the Klis defenders finally surrendered to the Ottomans in exchange for their freedom, on March 12, 1537.[4] Many of the citizens fled the town, while the Uskoci retreated to the city of Senj, where they continued fighting the Turkish invaders.[4]

Sanjak centre of Ottoman Bosnia

During the Ottoman wars in Europe, Klis Fortress was, for a century, an administrative centre or sanjak (Kilis Sancağı) of the Bosnia Eyalet.[4] On April 7, 1596, Split noblemen Ivan Alberti and Nikola Cindro, along with Uskoci, Poljičani, and Kaštelani irregulars, organized an occupation of Klis.[4] Assisted by dissident elements of the Turkish garrison, they succeeded.[4][30] Bey Mustafa responded by bringing more than 10,000 soldiers under the fortress.[4] General Ivan Lenković, leading 1,000 Uskoci, came in relief of the 1,500 Klis defenders.[4] During the battle, Ivan Lenković and his men retreated after he was wounded in battle, and the fortress was lost to the Turks, on May 31.[4] Nevertheless, this temporary relief resounded in Europe and among the local population.[4]

Petar Kružić fighting the Ottomans

From the well-fortified position in the Klis Fortress, the Turks were a constant threat to the Venetians and to the local Croatian population in the surrounding area. In 1647, after the Turkish success at Novigrad, the Turks were said to have 30,000 troops ready to attack Split.[31] The Signoria send off two thousand soldiers with munitions and provisions to the threatened area.[31] Although Split and Zadar were strong fortresses, they were clearly in danger.[31]

Venetian domination

In 1420, the Anjou contender Ladislaus of Naples was defeated and forced to sail away for Naples. Upon his departure he sold his "rights" to Dalmatia to the Venetian Republic for the relatively meager sum of 100,000 ducats. However, Klis and Klis Fortress remained parts of the Kingdom of Croatia.[2] From that time, the Venetians were eager to take control over Klis, as the fortress was one of the region's most important strategic points.[4]

The Venetians fought for decades before they finally managed to re-take Klis.[4] During the Candian War (1645–1669), the Venetians in Dalmatia enjoyed the support of the local population, particularly the Morlachs (Morlacchi).[4] Venetian commander Leonardo Foscolo seized several forts, retook Novigrad, temporarily captured the Knin Fortress, and managed to compel the garrison of Klis Fortress to surrender. At the same time, a month-long siege of the Šibenik Fortress by the Ottomans in August and September failed.[32][33]

From 1669, Klis Fortress was in the possession of the Venetians, and it remained so until the fall of the Venetian state.[4] The Venetians restored and enlarged the fortress during their rule.[2] After another, the seventh war with the Turks from 1714 to 1718, the Venetians were able to advance up to the present Bosnian/Croatian border, taking in the whole Sinjsko field and Imotski.[25] Thereafter the Turkish menace was laid to rest and Venice had no serious challenge to its authority in Dalmatia, until Napoleon extinguished the republic itself in 1797.[25] The border between Christian and Muslim Europe had been moved further east, and the fortress lost its main strategic importance.[2] Subsequently, Klis was taken by the Austrians.[4] The last military occupation of Klis Fortress was by Axis powers during World War II.[2]

Architecture

A view from the south-west at late afternoon

Klis Fortress seen from its west point, toward east.

Klis Fortress is one of the most valuable surviving examples of defensive architecture in Dalmatia.[2] The fortress is a remarkably comprehensive structure with three long rectangular defensive lines, consisting of three defensive stone walls, which are surrounding a central strongpoint, the "Položaj maggiore" at its eastern, highest end.[29] "Položaj maggiore" or "Grand position" is a mixed Croatian-Italian term, dating from the time when Leonardo Foscolo captured the fortress for the Venetians in 1648.[29] At that time, a village started to spread below the ramparts.[34] The structures of the fortress are mostly irregular, as they were constructed to suit the natural topography.[3] On the hills around Klis, there are several small towers, built by the Turks to keep the fortress under surveillance.[3]

Fortress outskirts

The Klis Fortress rises on a bare cliff divided into two parts.[2] The first, lower part is on the west, out topped by Mount Greben from the north.[2] The second, higher part is on the east, and includes the Tower "Oprah", whose name most likely refers to a specific part in the defense.[2] In this section which was not topped by any side, was located the flat of the Commander.[2] The only entrance into the fortress is from the western side.[2] On the southwest side of the fortress, and below it was a resort (part of the modern village of Klis) called "borgo" or "suburbium", surrounded by double walls with 100–200 towers.[2] A similar but smaller resort (also part of modern village of Klis) existed below Mount Greben on a plateau called Megdan.[2] This included lazarettoes and quarantines which were in Turkish times called "nazanama".[2] There were also many inns for travellers, which were used for isolation during epidemics.[2] Thus, the coastal towns, primarily the city of Split was protected from epidemics that came from Bosnia.[2] Near the fortress, there were several sources of drinking water, and the closest was the "Holy Biblical Magi" whose importance was invaluable during long sieges.[2]

Present appearance

View towards Split.

The fortress was built into the south face of a rocky mass, and is barely discernible from the distance as a man-made structure.[34] The defensive capabilities of the fortress have been tested through history in many military operations.[2] During the centuries of its use, the structure served various armies and has undergone a number of renovations, to keep up with the development of arms.[2] The original appearance of the fortress is no longer known, due to the structural changes undertaken by Croatian nobility, Turks, Venetians and Austrians.[2] The present day aspect of a mostly stone fortress dates back to the restructuring work carried out by the Venetians in the 17th century.[34]

First defensive line

Many buildings of the Klis Fortress which are from 17th through 19th centuries are partially or entirely preserved.[2] The Fortress actually consists of three parts, enclosed by walls with separate entrances.[2] The first main entrance was built by the Austrians in the early 19th century, on the place of an earlier Venetian entrance.[2] Left of the entrance there is a fortification erected by the Venetians in the early 18th century.[2] Also, near the main entrance there is a "position Avanzato" built in 1648, which was repeatedly renewed afterwards.[2] On the ground floor of the fortification there is a narrow over-vaulted corridor, which is called a Casemate.[2]

Second defensive line

Oprah tower guarding a second entrance.

The second entrance which was significantly damaged in the siege of 1648, leads to the former medieval part of the fortress previously ruled by a Croatian nobility.[2] After 1648, Venetians fully restored the second entrance, but its present appearance was made by the Austrians during the early 19th century.[2] Along the northern wall near the second entrance, there is fortress-tower called "Oprah", the most important medieval fortification of the western part of the fortress.[2] It was mentioned for the first time in 1355, but later the Venetians made the lower crown on it.[2] Nearby of the entrance are artillery barracks, built by the Austrians in the first half of the 19th century.[2] In 1931 its upper floor was ruined, so now only the ground floor remains.[2]

Third defensive line

Entrance to the third defensive line, through the third gate in a medieval tower.

Cannon in the castle

The third entrance leads to the former medieval part built in the early Middle Ages.[2] The Venetians renewed it several times after conquest in 1648, and the last upgrade was in 1763.[2] Within this part of the fortress there is the side tower, built during the 18th century, and completed in 1763.[2] Following is a repository of weapons built in the mid-17th century and old powder magazine from the 18th century.[2] "House of Dux" later called governor's residence was rebuilt in the mid-17th century on the foundations of the oldest buildings from the period of Croatian kings.[2] Austrians repaired this building, and there were placed commandments unity of the fortress and Engineering.[2] On the top point of the fortress there was a "New gunpowder storage", built in the early 19th century.[2]

The oldest remaining building with the dome and minaret, was a former square-shaped Turkish mosque, built after the conquest of Klis in 1537 on the foundations of an earlier Old Croatian Catholic chapel.[34] after occupation in 1648, the Venetians pulled down the minaret and converted it into a Roman Catholic church, dedicated to St. Vitus (Croatian: Crkva St. Vida).[2][34] It is a simple constructed square with the octagonal stone roof. There used to be three Altars, dedicated to St. Vid, Virgin Mary and St. Barbara, but today the church has no inventory.[2] In the church there is a Baroque stone sink from the 17th century, which served as a baptistery, where there is engraved the year of 1658.[2] West of the church is the bastion of Bembo, the largest artillery position in the third defense line and in the whole fortress.[2] It has wide holes for guns, and was built in the mid-17th century on the site of former Kružić's tower, and the defensive positions of Speranza.[2]

Present day

The Klis Fortress has been developed as a visitor attraction by the "Kliški uskoci" re-enactment association in Klis with the aid of the conservation department of the Ministry of Culture in Split.[35] Visitors to the historic military structure can see an array of arms, armor, and traditional uniforms in a building which was formerly an Austrian armory.[35] Klis is remembered in a Croatian byword based on the resistance of Klis and the strength of its people: It is difficult for Klis because it is on the rock and it is difficult for the rock because Klis is on it.[2]

In popular culture

The fortress was used in a 1972 historical film Eagle in a Cage, portraying Saint Helena.

Klis is also being used as a location for the fictional city of Meereen in the HBO series Game of Thrones.[36]

Gallery

"Kliški uskoci" re-enactment

Croatians battling the Ottomans

Large crowds gather to view the battle

Game of Thrones film set

View from the top of the fortress

See also

- List of castles in Croatia

- List of rulers of Croatia

- Timeline of Croatian history

Notes

- Footnotes

^ The actual nature of the relationship is inexplicable in modern terms because it varied from time to time. (Bellamy (2003), p. 38.) Sometimes Croatia acted as an independent agent and at other times as a vassal of Hungary. (Bellamy (2003), p. 38.) However, Croatia retained a large degree of internal independence. (Bellamy (2003), p. 38.) The degree of Croatian autonomy fluctuated throughout the centuries as did its borders. (Singleton (1989), p. 29.)

^ The Croatian nobles met in 1527 at Cetin and elected Ferdinand as their king, and confirmed the succession to him and his heirs. In return for the throne, Archduke Ferdinand promised to respect the historic rights, freedoms, laws, and customs the Croats had when united with the Hungarian kingdom and to defend Croatia from Ottoman invasion.[26] Between 1526 and the 1550s, the Kingdom of Hungary was embroiled in a succession dispute as well as the Little War.

- Citations

^ ab Hrvatski leksikon (1996), p. 470.

^ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzaaabacadaeafagahaiajakalamanaoapaqarasatauavawaxay "Klis –vrata Dalmacije" [Klis – A gateway to Dalmatia] (PDF). Građevinar (in Croatian). Zagreb: Croatian Society of Civil Engineers. 53 (9): 605–611. September 2001. ISSN 0350-2465. Retrieved 2009-12-17..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ abcdefghi Wilkinson (1848), pp. 169–172.

^ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuv Listeš, Srećko. "Povijest Klisa". klis.hr (in Croatian). Službene stranice Općine Klis. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

^ Royal Geographical Society (1856), p. 589.

^ ab Collection (1805), pp. 111–116.

^ abc Fine (The early medieval Balkans – 1991), p. 22.

^ ab Curta (2006), pp. 100–101.

^ abcd Fine (The early medieval Balkans – 1991), pp. 34–35.

^ Constantine Porphyrogenitus, De Administrando Imperio, ed. Gy. Moravcsik, trans. R.J.H. Jenkins, rev. ed., Washington, Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies, 1967.

^ Fine (The early medieval Balkans – 1991), p. 257.

^ abcdef Curta (2006), p. 139.

^ abc Hrvatski leksikon (1996), p. 1022.

^ http://www.historiografija.hr/Budak_HZ_2-2012.pdf

^ Fine (The early medieval Balkans – 1991), p. 263.

^ Regional Surveys of the World (1996), p. 271.

^ abcde Hunyadi and Laszlovszky (2001), p. 137.

^ abcd Archdeacon (2006), pp. 161–163.

^ abcdefgh Archdeacon (2006), p. 299.

^ abcdefgh Klaić V., Povijest Hrvata, Knjiga Prva, Druga, Treća, Četvrta i Peta Zagreb 1982. (in Croatian)

^ abc Fine (The Late Medieval Balkans – 1994), p. 206.

^ abcde Fine (The Late Medieval Balkans – 1994), pp. 207–208.

^ abc Fine (The Late Medieval Balkans – 1994), pp. 208–209.

^ abcdef Fine (The Late Medieval Balkans – 1994), pp. 209–210.

^ abcdefg Singleton (1989), pp. 60–62.

^ R. W. Seton -Watson:The southern Slav question and the Habsburg Monarchy page 18

^ abcdefg Setton (1984), p. 421.

^ ab Spandouginos (1997), p. 75.

^ abcde Bousfield (2003), p. 313.

^ Setton (1984), p. 9.

^ abc Setton (1984), p. 144.

^ Fraser (1854), pp. 244–245.

^ Setton (1991), pp. 148–149.

^ abcde Foster (2004), p. 215.

^ ab Mihovilović, Sreten. "Otvorena "Uskočka oružarnica"". kliskiuskoci.hr (in Croatian). Povijesna postrojba „Kliški uskoci“. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

^ http://winteriscoming.net/2013/09/new-set-photos-from-klis-and-dubrovnik/

References

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Archdeacon, Thomas of Split (2006). History of the Bishops of Salona and Split – Historia Salonitanorum atque Spalatinorum pontificum (in Latin and English). Budapest: Central European University Press. ISBN 9789637326592.

Bellamy, Alex J (2003). The Formation of Croatian National Identity: A Centuries-old Dream. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-6502-X.

Bousfield, Jonathan (2003). The Rough Guide to Croatia. London: Rough Guides. ISBN 9781843530848.

Collection (1805). A Collection of Modern and Contemporary Voyages & Travels Vol I. London: Oxford University.

Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89452-4.

Fine, John Van Antwerp (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Michigan: The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

Fine, John Van Antwerp (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Michigan: The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0472100798.

Foster, Jane (2004). Footprint Croatia. Footprint Travel Guides. ISBN 1-903471-79-6.

Fraser, Robert William (1854). Turkey, Ancient and Modern. A History of the Ottoman Empire From the Period of Its Establishment to the Present Time. Edinburgh: Adam & Charles Black – Harvard University. ISBN 978-1-4021-2562-1.

Hrvatski Opći Leksikon (in Croatian). Zagreb: Miroslav Krleža Lexicographical Institute. 1996. ISBN 953-6036-62-2.

Hunyadi and Laszlovszky, Zsolt and József (2001). The Crusades and the Military Orders: Expanding the Frontiers of Medieval Latin Christianity. Budapest: Central European University Press. Dept. of Medieval Studies. ISBN 963-9241-42-3.

Klaić, Vjekoslav (1985). Povijest Hrvata: Knjiga Prva, Druga, Treća, Četvrta i Peta (in Croatian). Zagreb: Nakladni zavod Matice hrvatske. ISBN 9788640100519.

Regional Surveys of the World (1996). Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States, Fourth Edition. London: Europa Publications Limited. ISBN 1-85743-058-1.

Royal Geographical Society (Great Britain) (1856). A Gazetteer of the World: AA-Brazey. London, Dublin: A. Fullarton & Co. – Oxford University.

Setton, Kenneth Meyer (1984). The Papacy and the Levant, 1204–1571: The Sixteenth Century, Vol. III. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. ISBN 0-87169-161-2.

Setton, Kenneth Meyer (1991). Venice, Austria, and the Turks in the Seventeenth Century. Philadelphia: Diane Publishing. ISBN 0-87169-192-2.

Singleton, Frederick Bernard (1989). A Short History of the Yugoslav Peoples. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521274852.

Spandouginos, Theodore (1997). On the Origin of the Ottoman Emperors. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521585101.

Wilkinson, Sir John Gardner (2005) [1848]. Dalmatia and Montenegro: With a Journey to Mostar in Herzegovina. I. London: John Murray – Harvard College Library. ISBN 9781446043615.

Further reading

Listeš, Srećko (1998). Klis: Prošlost, Toponimi, Govor (in Croatian). Klis: Hrvatsko društvo Trpimir. ISBN 9789539675132.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Klis Fortress. |

Musulin, Nedjeljko (2009-11-04). "Kliška tvrđava, najveći muzej na otvorenome, pristupačnija turistima - Kliški uskoci opet čuvaju puteve do Dalmacije" [Klis fortress, the largest museum in the open, more accessible to tourists - Uskoci of Klis guard the roads of Dalmatia once again] (PDF). Vjesnik (in Croatian). Retrieved 2011-03-13.

- Webcam from top of the Klis fortress

Comments

Post a Comment