Cost of electricity by source

The distinct ways of electricity generation can incur significantly different costs. Calculations of these costs can be made at the point of connection to a load or to the electricity grid. The cost is typically given per kilowatt-hour or megawatt-hour. It includes the initial capital, discount rate, as well as the costs of continuous operation, fuel, and maintenance. This type of calculation assists policymakers, researchers and others to guide discussions and decision making.

The levelized cost of energy (LCOE) is a measure of a power source that allows comparison of different methods of electricity generation on a consistent basis. It is an economic assessment of the average total cost to build and operate a power-generating asset over its lifetime divided by the total energy output of the asset over that lifetime. The LCOE can also be regarded as the average minimum price at which electricity must be sold in order to break-even over the lifetime of the project.

Contents

1 Cost factors

1.1 Capital costs

1.2 Levelized cost of electricity

1.3 Avoided cost

1.4 Marginal cost of electricity

1.5 External costs of energy sources

1.6 Additional cost factors

2 Current global studies

2.1 Lazard (2018)

2.2 Bloomberg (2018)

2.3 IRENA (2018)

2.4 Banks (2018)

3 Regional and historical studies

3.1 Australia

3.2 France

3.3 Germany

3.4 Japan

3.5 United Kingdom

3.6 United States

3.6.1 Energy Information Administration

3.6.2 NREL OpenEI (2015)

3.6.3 California Energy Commission (2014)

3.6.4 Lazard (2015)

3.6.5 Lazard (2016)

3.6.6 Lazard (2017)

3.7 Global

3.7.1 IEA and NEA (2015)

3.8 Other studies and analysis

3.8.1 Buffett Contract (2015)

3.8.2 Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid solar farm (2016)

3.8.3 Brookings Institution (2014)

3.8.4 Brazilian electricity mix: the Renewable and Non-renewable Exergetic Cost (2014)

4 Renewables

4.1 Photovoltaics

4.2 Solar thermal

4.3 Wind power

5 See also

6 Further reading

7 References

Cost factors

While calculating costs, several internal cost factors have to be considered.[1] Note the use of "costs," which is not the actual selling price, since this can be affected by a variety of factors such as subsidies and taxes:

Capital costs (including waste disposal and decommissioning costs for nuclear energy) – tend to be low for fossil fuel power stations; high for wind turbines, solar PV (photovoltaics); very high for waste to energy, wave and tidal, solar thermal, and nuclear.- Fuel costs – high for fossil fuel and biomass sources, low for nuclear, and zero for many renewables. Fuel costs can vary somewhat unpredictably over the life of the generating equipment, due to political and other factors.

- Factors such as the costs of waste (and associated issues) and different insurance costs are not included in the following: Works power, own use or parasitic load – that is, the portion of generated power actually used to run the station's pumps and fans has to be allowed for.

To evaluate the total cost of production of electricity, the streams of costs are converted to a net present value using the time value of money. These costs are all brought together using discounted cash flow.[2][3]

Capital costs

For power generation capacity capital costs are often expressed as overnight cost per watt. The EIA 2019 estimates are:

- gas/oil combined cycle power plant - $1000/kW [4]

- fuel cells - $7200/kW[4]

- advanced nuclear - $6000/kW[4]

- battery storage - $2000/kW[4]

- geothermal - $2800/kW[4]

- wind - $1600/kW[4]

- offshore wind - $6500/kW[4]

- solar PV (tracking)- $2000/kW[4]

- solar PV (fixed) - $1800/kW[4]

Levelized cost of electricity

The levelized cost of electricity (LCOE), also known as Levelized Energy Cost (LEC), is the net present value of the unit-cost of electricity over the lifetime of a generating asset. It is often taken as a proxy for the average price that the generating asset must receive in a market to break even over its lifetime. It is a first-order economic assessment of the cost competitiveness of an electricity-generating system that incorporates all costs over its lifetime: initial investment, operations and maintenance, cost of fuel, cost of capital.

The levelized cost is that value for which an equal-valued fixed revenue delivered over the life of the asset's generating profile would cause the project to break even. This can be roughly calculated as the net present value of all costs over the lifetime of the asset divided by the total electrical energy output of the asset.[5]

The levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) is given by:

- LCOE=sum of costs over lifetimesum of electrical energy produced over lifetime=∑t=1nIt+Mt+Ft(1+r)t∑t=1nEt(1+r)t{displaystyle mathrm {LCOE} ={frac {text{sum of costs over lifetime}}{text{sum of electrical energy produced over lifetime}}}={frac {sum _{t=1}^{n}{frac {I_{t}+M_{t}+F_{t}}{left({1+r}right)^{t}}}}{sum _{t=1}^{n}{frac {E_{t}}{left({1+r}right)^{t}}}}}}

It : investment expenditures in the year t

Mt :

operations and maintenance expenditures in the year t

Ft : fuel expenditures in the year t

Et : electrical energy generated in the year t

r :

discount rate

n :

expected lifetime of system or power station

- Note: Some caution must be taken when using formulas for the levelized cost, as they often embody unseen assumptions, neglect effects like taxes, and may be specified in real or nominal levelized cost. For example, other versions of the above formula do not discount the electricity stream.[citation needed]

Typically the LCOE is calculated over the design lifetime of a plant, which is usually 20 to 40 years, and given in the units of currency per kilowatt-hour or megawatt-day, for example AUD/kWh or EUR/kWh or per megawatt-hour, for example AUD/MWh (as tabulated below).[6] However, care should be taken in comparing different LCOE studies and the sources of the information as the LCOE for a given energy source is highly dependent on the assumptions, financing terms and technological deployment analyzed.[7] In particular, assumption of capacity factor has significant impact on the calculation of LCOE. Thus, a key requirement for the analysis is a clear statement of the applicability of the analysis based on justified assumptions.[7]

Many scholars,[specify] such as Paul Joskow, have described limits to the "levelized cost of electricity" metric for comparing new generating sources. In particular, LCOE ignores time effects associated with matching production to demand. This happens at two levels:

- Dispatchability, the ability of a generating system to come online, go offline, or ramp up or down, quickly as demand swings.

- The extent to which the availability profile matches or conflicts with the market demand profile.

Thermally lethargic technologies like coal and nuclear are physically incapable of fast ramping. Capital intensive technologies such as wind, solar, and nuclear are economically disadvantaged unless generating at maximum availability since the LCOE is nearly all sunk-cost capital investment. Intermittent power sources, such as wind and solar, may incur extra costs associated with needing to have storage or backup generation available.[8] At the same time, intermittent sources can be competitive if they are available to produce when demand and prices are highest, such as solar during summertime mid-day peaks seen in hot countries where air conditioning is a major consumer.[7] Despite these time limitations, leveling costs is often a necessary prerequisite for making comparisons on an equal footing before demand profiles are considered, and the levelized-cost metric is widely used for comparing technologies at the margin, where grid implications of new generation can be neglected.

Another limitation of the LCOE metric is the influence of energy efficiency and conservation (EEC).[9]

EEC has caused the electricity demand of many countries to remain flat or decline. Considering only the LCOE for utility scale plants will tend to maximise generation and risks overestimating required generation due to efficiency, thus "lowballing" their LCOE. For solar systems installed at the point of end use, it is more economical to invest in EEC first, then solar (resulting in a smaller required solar system than what would be needed without the EEC measures). However, designing a solar system on the basis of LCOE would cause the smaller system LCOE to increase (as the energy generation [measured in kWh] drops faster than the system cost [$]). The whole of system life cycle cost should be considered, not just the LCOE of the energy source.[9] LCOE is not as relevant to end-users than other financial considerations such as income, cashflow, mortgage, leases, rent, and electricity bills.[9] Comparing solar investments in relation to these can make it easier for end-users to make a decision, or using cost-benefit calculations "and/or an asset’s capacity value or contribution to peak on a system or circuit level".[9]

Avoided cost

The US Energy Information Administration has recommended that levelized costs of non-dispatchable sources such as wind or solar may be better compared to the avoided energy cost rather than to the LCOE of dispatchable sources such as fossil fuels or geothermal. This is because introduction of fluctuating power sources may or may not avoid capital and maintenance costs of backup dispatchable sources. Levelized Avoided Cost of Energy (LACE) is the avoided costs from other sources divided by the annual yearly output of the non-dispatchable source. However, the avoided cost is much harder to calculate accurately.[10][11]

Marginal cost of electricity

A more accurate economic assessment might be the marginal cost of electricity. This value works by comparing the added system cost of increasing electricity generation from one source versus that from other sources of electricity generation (see Merit Order).[citation needed][12]

External costs of energy sources

Typically pricing of electricity from various energy sources may not include all external costs – that is, the costs indirectly borne by society as a whole as a consequence of using that energy source.[13] These may include enabling costs, environmental impacts, usage lifespans, energy storage, recycling costs, or beyond-insurance accident effects.

The US Energy Information Administration predicts that coal and gas are set to be continually used to deliver the majority of the world's electricity.[14] This is expected to result in the evacuation of millions of homes in low-lying areas, and an annual cost of hundreds of billions of dollars' worth of property damage.[15][16][17][18][19][20][21]

Furthermore, with a number of island nations becoming slowly submerged underwater due to rising sea levels,[22] massive international climate litigation lawsuits against fossil fuel users are currently[when?] beginning in the International Court of Justice.[23][24]

An EU funded research study known as ExternE, or Externalities of Energy, undertaken over the period of 1995 to 2005 found that the cost of producing electricity from coal or oil would double over its present value, and the cost of electricity production from gas would increase by 30% if external costs such as damage to the environment and to human health, from the particulate matter, nitrogen oxides, chromium VI, river water alkalinity, mercury poisoning and arsenic emissions produced by these sources, were taken into account. It was estimated in the study that these external, downstream, fossil fuel costs amount up to 1%–2% of the EU’s entire Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and this was before the external cost of global warming from these sources was even included.[25][26] Coal has the highest external cost in the EU, and global warming is the largest part of that cost.[13]

A means to address a part of the external costs of fossil fuel generation is carbon pricing — the method most favored by economics for reducing global-warming emissions. Carbon pricing charges those who emit carbon dioxide (CO2) for their emissions. That charge, called a 'carbon price', is the amount that must be paid for the right to emit one tonne of CO2 into the atmosphere.[27] Carbon pricing usually takes the form of a carbon tax or a requirement to purchase permits to emit (also called "allowances").

Depending on the assumptions of possible accidents and their probabilites external costs for nuclear power vary significantly and can reach between 0.2 and 200 ct/kWh.[28] Furthermore, nuclear power is working under an insurance framework that limits or structures accident liabilities in accordance with the Paris convention on nuclear third-party liability, the Brussels supplementary convention, and the Vienna convention on civil liability for nuclear damage[29] and in the U.S. the Price-Anderson Act. It is often argued that this potential shortfall in liability represents an external cost not included in the cost of nuclear electricity; but the cost is small, amounting to about 0.1% of the levelized cost of electricity, according to a CBO study.[30]

These beyond-insurance costs for worst-case scenarios are not unique to nuclear power, as hydroelectric power plants are similarly not fully insured against a catastrophic event such as the Banqiao Dam disaster, where 11 million people lost their homes and from 30,000 to 200,000 people died, or large dam failures in general. As private insurers base dam insurance premiums on limited scenarios, major disaster insurance in this sector is likewise provided by the state.[31]

Because externalities are diffuse in their effect, external costs can not be measured directly, but must be estimated. One approach estimate external costs of environmental impact of electricity is the Methodological Convention of Federal Environment Agency of Germany. That method arrives at external costs of electricity from lignite at 10.75 Eurocent/kWh, from hard coal 8.94 Eurocent/kWh, from natural gas 4.91 Eurocent/kWh, from photovoltaic 1.18 Eurocent/kWh, from wind 0.26 Eurocent/kWh and from hydro 0.18 Eurocent/kWh.[32] For nuclear the Federal Environment Agency indicates no value, as different studies have results that vary by a factor of 1,000. It recommends the nuclear given the huge uncertainty, with the cost of the next inferior energy source to evaluate.[33] Based on this recommendation the Federal Environment Agency, and with their own method, the Forum Ecological-social market economy, arrive at external environmental costs of nuclear energy at 10.7 to 34 ct/kWh.[34]

Additional cost factors

Calculations often do not include wider system costs associated with each type of plant, such as long distance transmission connections to grids, or balancing and reserve costs. Calculations do not include externalities such as health damage by coal plants, nor the effect of CO2 emissions on the climate change, ocean acidification and eutrophication, ocean current shifts. Decommissioning costs of nuclear plants are usually not included (The USA is an exception, because the cost of decommissioning is included in the price of electricity, per the Nuclear Waste Policy Act), is therefore not full cost accounting. These types of items can be explicitly added as necessary depending on the purpose of the calculation. It has little relation to actual price of power, but assists policy makers and others to guide discussions and decision making.[citation needed]

These are not minor factors but very significantly affect all responsible power decisions:

Comparisons of life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions show coal, for instance, to be radically higher in terms of GHGs than any alternative. Accordingly, in the analysis below, carbon captured coal is generally treated as a separate source rather than being averaged in with other coal.

- Other environmental concerns with electricity generation include acid rain, ocean acidification and effect of coal extraction on watersheds.

- Various human health concerns with electricity generation, including asthma and smog, now dominate decisions in developed nations that incur health care costs publicly. A Harvard University Medical School study estimates the US health costs of coal alone at between 300 and 500 billion US dollars annually.[35]

- While cost per kWh of transmission varies drastically with distance, the long complex projects required to clear or even upgrade transmission routes make even attractive new supplies often uncompetitive with conservation measures (see below), because the timing of payoff must take the transmission upgrade into account.

Current global studies

Lazard (2018)

In November, 2018, Lazard found that not only are utility-scale solar and wind cheaper than fossil fuels, "[i]n some scenarios, alternative energy costs have decreased to the point that they are now at or below the marginal cost of conventional generation."

Overall, Lazard found "The low end levelized cost of onshore wind-generated energy is $29/MWh, compared to an average illustrative marginal cost of $36/MWh for coal. The levelized cost of utility-scale solar is nearly identical to the illustrative marginal cost of coal, at $36/MWh. This comparison is accentuated when subsidizing onshore wind and solar, which results in levelized costs of energy of $14/MWh and $32/MWh, respectively. ... The mean levelized cost of energy of utility-scale PV technologies is down approximately 13% from last year and the mean levelized cost of energy of onshore wind has declined almost 7%."[36]

Bloomberg (2018)

Bloomberg New Energy Finance estimates a "global LCOE for onshore wind [of] $55 per megawatt-hour, down 18% from the first six months of [2017], while the equivalent for solar PV without tracking systems is $70 per MWh, also down 18%." Bloomberg does not provide its global public LCOEs for fossil fuels, but it notes in India they are significantly more expensive: "BNEF is now showing benchmark LCOEs for onshore wind of just $39 per MWh, down 46% on a year ago, and for solar PV at $41, down 45%. By comparison, coal comes in at $68 per MWh, and combined-cycle gas at $93." [37][38]

IRENA (2018)

The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) released a study based on comprehensive international datasets in January 2018 which projects the fall by 2020 of the kilowatt cost of electricity from utility scale renewable projects such as onshore wind farms to a point equal or below that of electricity from conventional sources.[39]

Banks (2018)

The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) says that "renewables are now cheapest energy source", elaborating: "the Bank believes that renewable energy markets in many of the countries where it invests have reached a stage where the introduction of competitive auctions will lead both to a steep drop in electricity prices and an increase in investment." [40] The World Bank (World Bank) President Jim Yong Kim agreed on 10 October 2018: "We are required by our by-laws to go with the lowest cost option, and renewables have now come below the cost of [fossil fuels]." [41]

Regional and historical studies

Australia

| Technology | Cost with CO 2 price |

Cost without CO 2 price |

|---|---|---|

| Supercritical brown coal | $162 | $95 |

| Supercritical brown coal with CCS | $205 | $192 |

| Supercritical black coal | $135 – $145 | $84 – $94 |

| Supercritical black coal with CCS | $162 – $205 | $153 – $196 |

| Wind | $111 – $122 | $111 – $122 |

LCOEs by source in Australia in 2012.

According to various studies, the cost for wind and solar has dramatically reduced since 2006. For example, the Australian Climate Council states that over the 5 years between 2009–2014 solar costs fell by 75% making them comparable to coal, and are expected to continue dropping over the next 5 years by another 45% from 2014 prices.[43] They also found that wind has been cheaper than coal since 2013, and that coal and gas will become less viable as subsidies are withdrawn and there is the expectation that they will eventually have to pay the costs of pollution.[43]

A CO2CRC report, printed on the 27th of November 2015, titled "Wind, solar, coal and gas to reach similar costs by 2030:", provides the following updated situation in Australia. "The updated LCOE analysis finds that in 2015 natural gas combined cycle and supercritical pulverised coal (both black and brown) plants have the lowest LCOEs of the technologies covered in the study. Wind is the lowest cost large-scale renewable energy source, while rooftop solar panels are competitive with retail electricity prices. By 2030 the LCOE ranges of both conventional coal and gas technologies as well as wind and large-scale solar converge to a common range of A$50 to A$100 per megawatt hour."

An updated report, posted on the 27th of September 2017, titled "Renewables will be cheaper than coal in the future. Here are the numbers", indicated that a 100% renewables system is competitive with new-build supercritical (ultrasupercritical) coal, which, according to the Jacobs calculations in the report link above, would come in at around A$75(80) per MWh between 2020 and 2050. This projection for supercritical coal is consistent with other studies by the CO2CRC in 2015 (A$80 per MWh) and used by CSIRO in 2017 (A$65-80 per MWh).

France

The International Energy Agency and EDF have estimated for 2011 the following costs.[citation needed] For nuclear power, they include the costs due to new safety investments to upgrade the French nuclear plant after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster; the cost for those investments is estimated at 4 €/MWh. Concerning solar power, the estimate of 293 €/MWh is for a large plant capable of producing in the range of 50–100 GWh/year located in a favorable location (such as in Southern Europe). For a small household plant that can produce around 3 MWh/year, the cost is between 400 and 700 €/MWh, depending on location. Solar power was by far the most expensive renewable source of electricity among the technologies studied, although increasing efficiency and longer lifespan of photovoltaic panels together with reduced production costs have made this source of energy more competitive since 2011. By 2017, the cost of photovoltaic solar power had decreased to less than 50 €/MWh.

| Technology | Cost in 2011 | Cost in 2017 |

|---|---|---|

| Hydro power | 20 | |

| Nuclear (with State-covered insurance costs) | 50 | 50 |

| Nuclear EPR |

100[44] |

|

| Natural gas turbines without CO2 capture | 61 | |

| Onshore wind | 69 | 60[44] |

| Solar farms | 293 | 43.24[45] |

Germany

Comparison of the levelized cost of electricity for some newly built renewable and fossil-fuel based power stations in EuroCent per kWh (Germany, 2018)[46]

Note: employed technologies and LCOE differ by country and change over time.

In November 2013, the Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems ISE assessed the levelised generation costs for newly built power plants in the German electricity sector.[47]PV systems reached LCOE between 0.078 and 0.142 Euro/kWh in the third quarter of 2013, depending on the type of power plant (ground-mounted utility-scale or small rooftop solar PV) and average German insolation of 1000 to 1200 kWh/m² per year (GHI). There are no LCOE-figures available for electricity generated by recently built German nuclear power plants as none have been constructed since the late 1980s. An update of the ISE study was published in March 2018[46].

| ISE (2013) | ISE (2018) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technology | Low cost | High cost | Low cost | High cost |

|||

| Coal-fired power plants | brown coal | 38 | 53 | 46 | 80 |

||

| hard coal | 63 | 80 | 63 | 99 |

|||

CCGT power plants |

75 | 98 | 78 | 100 |

|||

| Wind Power | Onshore wind farms | 45 | 107 | 40 | 82 |

||

| Offshore wind farms | 119 | 194 | 75 | 138 |

|||

| Solar | PV systems | 78 | 142 | 37 | 115 |

||

| Biogas power plant | 135 | 250 | 101 | 147 |

|||

| Source: Fraunhofer ISE (2013) – Levelized cost of electricity renewable energy technologies[47] Source: Fraunhofer ISE (2018) – Stromgestehungskosten erneuerbare Energien[46] | |||||||

Japan

A 2010 study by the Japanese government (pre-Fukushima disaster), called the Energy White Paper,[citation needed] concluded the cost for kilowatt hour was ¥49 for solar, ¥10 to ¥14 for wind, and ¥5 or ¥6 for nuclear power. Masayoshi Son, an advocate for renewable energy, however, has pointed out that the government estimates for nuclear power did not include the costs for reprocessing the fuel or disaster insurance liability. Son estimated that if these costs were included, the cost of nuclear power was about the same as wind power.[48][49][50]

United Kingdom

The Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders in Scotland commissioned a former Director of Operations of the British National Grid, Colin Gibson, to produce a report on generation levelised costs that for the first time would include some of the transmission costs as well as the generation costs. This was published in December 2011.[51] The institution seeks to encourage debate of the issue, and has taken the unusual step among compilers of such studies of publishing a spreadsheet.[52]

On 27 February 2015 Vattenfall Vindkraft AS agreed to build the Horns Rev 3 offshore wind farm at a price of 10.31 Eurocent per kWh. This has been quoted as below £100 per MWh.

In 2013 in the United Kingdom for a new-to-build nuclear power plant (Hinkley Point C: completion 2023), a feed-in tariff of £92.50/MWh (around 142 USD/MWh) plus compensation for inflation with a running time of 35 years was agreed.[53][54]

The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) publishes regular estimates of the costs of different electricity generation sources, following on the estimates of the merged Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC). Levelised cost estimates for new generation projects begun in 2015 are listed in the table below.[55]

| Power generating technology | Low | Central | High |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear PWR (Pressurized Water Reactor)(a) |

82 | 93 | 121 |

|

Solar Large-scale PV (Photovoltaic) |

71 | 80 | 94 |

|

| Wind | Onshore | 47 | 62 | 76 |

| Offshore | 90 | 102 | 115 |

|

| Biomass | 85 | 87 | 88 |

|

| Natural Gas | Combined Cycle Gas Turbine | 65 | 66 | 68 |

| CCGT with CCS (Carbon capture and storage) |

102 | 110 | 123 |

|

| Open-Cycle Gas Turbine | 157 | 162 | 170 |

|

| Coal | Advanced Supercritical Coal with Oxy-comb. CCS | 124 | 134 | 153 |

IGCC (Integrated Gasification Combined Cycle) with CCS |

137 | 148 | 171 |

|

(a) new nuclear power: guaranteed strike price of £92.50/MWh for Hinkley Point C in 2023[56][57]) | ||||

United States

Energy Information Administration

Projected LCOE in the U.S. by 2020 (as of 2015) in dollars per MWh[58]

The following data are from the Energy Information Administration's (EIA) Annual Energy Outlook released in 2015 (AEO2015). They are in dollars per megawatt-hour (2013 USD/MWh). These figures are estimates for plants going into service in 2020.[11] The LCOE below is calculated based off a 30-year recovery period using a real after tax weighted average cost of capital (WACC) of 6.1%. For carbon intensive technologies 3 percentage points are added to the WACC. (This is approximately equivalent fee of $15 per metric ton of carbon dioxide CO

2)

Since 2010, the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) has published the Annual Energy Outlook (AEO), with yearly LCOE-projections for future utility-scale facilities to be commissioned in about five years' time. In 2015, EIA has been criticized by the Advanced Energy Economy (AEE) Institute after its release of the AEO 2015-report to "consistently underestimate the growth rate of renewable energy, leading to 'misperceptions' about the performance of these resources in the marketplace". AEE points out that the average power purchase agreement (PPA) for wind power was already at $24/MWh in 2013. Likewise, PPA for utility-scale solar PV are seen at current levels of $50–$75/MWh.[59] These figures contrast strongly with EIA's estimated LCOE of $125/MWh (or $114/MWh including subsidies) for solar PV in 2020.[60]

| Plant Type |

Min |

Capacity Weighted Average |

Max |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coal with 30% carbon sequestration |

128.9 |

NB |

196.3 |

| Coal with 90% carbon sequestration |

102.7 |

NB |

142.5 |

| Natural Gas-fired Conventional Combined Cycle |

52.4 |

58.6 |

83.2 |

| Natural Gas-fired Advanced Combined Cycle |

51.6 |

53.8 |

81.7 |

| Natural Gas-fired Advanced CC with CCS |

63.1 |

NB |

90.4 |

| Natural Gas-fired Conventional Combustion Turbine |

98.8 |

100.7 |

148.3 |

| Natural Gas-fired Advanced Combustion Turbine |

85.9 |

87.1 |

129.8 |

| Advanced Nuclear |

95.9 |

96.2 |

104.3 |

| Geothermal |

42.8 |

44.0 |

53.4 |

| Biomass |

84.8 |

97.7 |

125.3 |

| Wind Onshore |

43.4 |

55.8 |

75.6 |

| Wind Offshore |

136.6 |

NB |

212.9 |

| Solar PV |

58.3 |

73.7 |

143.0 |

| Solar Thermal |

176.7 |

NB |

372.8 |

| Hydro |

57.4 |

63.9 |

69.8 |

The electricity sources which had the most decrease in estimated costs over the period 2010 to 2019 were solar photovoltaic (down 88%), onshore wind (down 71%) and advanced natural gas combined cycle (down 49%).

For utility-scale generation put into service in 2040, the EIA estimated in 2015 that there would be further reductions in the constant-dollar cost of concentrated solar power (CSP) (down 18%), solar photovoltaic (down 15%), offshore wind (down 11%), and advanced nuclear (down 7%). The cost of onshore wind was expected to rise slightly (up 2%) by 2040, while natural gas combined cycle electricity was expected to increase 9% to 10% over the period.[60]

| Estimate in $/MWh |

Coal convent'l |

Nat. Gas combined cycle |

Nuclear advanced |

Wind |

Solar |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| of year |

ref |

for year |

convent'l |

advanced |

onshore |

offshore |

PV |

CSP |

||

| 2010 | [61] | 2016 | 100.4 | 83.1 | 79.3 | 119.0 | 149.3 | 191.1 | 396.1 | 256.6 |

| 2011 | [62] | 2016 | 95.1 | 65.1 | 62.2 | 114.0 | 96.1 | 243.7 | 211.0 | 312.2 |

| 2012 | [63] | 2017 | 97.7 | 66.1 | 63.1 | 111.4 | 96.0 | N/A | 152.4 | 242.0 |

| 2013 | [64] | 2018 | 100.1 | 67.1 | 65.6 | 108.4 | 86.6 | 221.5 | 144.3 | 261.5 |

| 2014 | [65] | 2019 | 95.6 | 66.3 | 64.4 | 96.1 | 80.3 | 204.1 | 130.0 | 243.1 |

| 2015 | [60] | 2020 | 95.1 | 75.2 | 72.6 | 95.2 | 73.6 | 196.9 | 125.3 | 239.7 |

| 2016 | [66] | 2022 | NB | 58.1 | 57.2 | 102.8 | 64.5 | 158.1 | 84.7 | 235.9 |

| 2017 | [67] | 2022 | NB | 58.6 | 53.8 | 96.2 | 55.8 | NB | 73.7 | NB |

| 2018 | [68] | 2022 | NB | 48.3 | 48.1 | 90.1 | 48.0 | 124.6 | 59.1 | NB |

| 2019 | [69] | 2023 | NB | 40.8 | 40.2 | NB | 42.8 | 117.9 | 48.8 | NB |

| Nominal change 2010–2019 | NB | −48% | −49% | NB | −71% | -38% | −88% | NB |

||

Note: Projected LCOE are adjusted for inflation and calculated on constant dollars based on two years prior to the release year of the estimate. Estimates given without any subsidies. Transmission cost for non-dispatchable sources are on average much higher. NB = "Not built" (No capacity additions are expected.) | ||||||||||

NREL OpenEI (2015)

OpenEI, sponsored jointly by the US DOE and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), has compiled a historical cost-of-generation database[70] covering a wide variety of generation sources. Because the data is open source it may be subject to frequent revision.

| Plant Type (USD/MWh) | Min | Median | Max | Data Source Year |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distributed Generation | 10 | 70 | 130 | 2014 |

|

| Hydropower | Conventional | 30 | 70 | 100 | 2011 |

| Small Hydropower | 140 | 2011 |

|||

| Wind | Onshore (land based) | 40 | 80 | 2014 |

|

| Offshore | 100 | 200 | 2014 |

||

| Natural Gas | Combined Cycle | 50 | 80 | 2014 |

|

| Combustion Turbine | 140 | 200 | 2014 |

||

| Coal | Pulverized, scrubbed | 60 | 150 | 2014 |

|

| Pulverized, unscrubbed | 40 | 2008 |

|||

IGCC, gasified |

100 | 170 | 2014 |

||

| Solar | Photovoltaic | 60 | 110 | 250 | 2014 |

| CSP | 100 | 220 | 2014 |

||

| Geothermal | Hydrothermal | 50 | 100 | 2011 |

|

| Blind | 100 | 2011 |

|||

| Enhanced | 80 | 130 | 2014 |

||

| Biopower | 90 | 110 | 2014 |

||

| Fuel Cell | 100 | 160 | 2014 |

||

| Nuclear | 90 | 130 | 2014 |

||

| Ocean | 230 | 240 | 250 | 2011 |

|

Note:

Only Median value = only one data point.

Only Max + Min value = Only two data points

California Energy Commission (2014)

LCOE data from the California Energy Commission report titled "Estimated Cost of New Renewable and Fossil Generation in California".[71] The model data was calculated for all three classes of developers: merchant, investor-owned utility (IOU), and publicly owned utility (POU).

| Type |

Year 2013 (Nominal $$) ($/MWh) |

Year 2024( Nominal $$) ($/MWh) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name |

Merchant |

IOU |

POU |

Merchant |

IOU |

POU |

| Generation Turbine 49.9 MW |

662.81 |

2215.54 |

311.27 |

884.24 |

2895.90 |

428.20 |

| Generation Turbine 100 MW |

660.52 |

2202.75 |

309.78 |

881.62 |

2880.53 |

426.48 |

| Generation Turbine – Advanced 200 MW |

403.83 |

1266.91 |

215.53 |

533.17 |

1615.68 |

299.06 |

| Combined Cycle 2CTs No Duct Firing 500 MW |

116.51 |

104.54 |

102.32 |

167.46 |

151.88 |

150.07 |

| Combined Cycle 2CTs With Duct Firing 500 MW |

115.81 |

104.05 |

102.04 |

166.97 |

151.54 |

149.88 |

| Biomass Fluidized Bed Boiler 50 MW |

122.04 |

141.53 |

123.51 |

153.89 |

178.06 |

156.23 |

| Geothermal Binary 30 MW |

90.63 |

120.21 |

84.98 |

109.68 |

145.31 |

103.00 |

| Geothermal Flash 30 MW |

112.48 |

146.72 |

109.47 |

144.03 |

185.85 |

142.43 |

| Solar Parabolic Trough W/O Storage 250 MW |

168.18 |

228.73 |

167.93 |

156.10 |

209.72 |

156.69 |

| Solar Parabolic Trough With Storage 250 MW |

127.40 |

189.12 |

134.81 |

116.90 |

171.34 |

123.92 |

| Solar Power Tower W/O Storage 100 MW |

152.58 |

210.04 |

151.53 |

133.63 |

184.24 |

132.69 |

| Solar Power Tower With Storage 100 MW 6HR |

145.52 |

217.79 |

153.81 |

132.78 |

196.47 |

140.58 |

| Solar Power Tower With Storage 100 MW 11HR |

114.06 |

171.72 |

120.45 |

103.56 |

154.26 |

109.55 |

| Solar Photovoltaic (Thin Film) 100 MW |

111.07 |

170.00 |

121.30 |

81.07 |

119.10 |

88.91 |

| Solar Photovoltaic (Single-Axis) 100 MW |

109.00 |

165.22 |

116.57 |

98.49 |

146.20 |

105.56 |

| Solar Photovoltaic (Thin Film) 20 MW |

121.31 |

186.51 |

132.42 |

93.11 |

138.54 |

101.99 |

| Solar Photovoltaic (Single-Axis) 20 MW |

117.74 |

179.16 |

125.86 |

108.81 |

162.68 |

116.56 |

| Wind Class 3 100 MW |

85.12 |

104.74 |

75.8 |

75.01 |

91.90 |

68.17 |

| Wind Class 4 100 MW |

84.31 |

103.99 |

75.29 |

75.77 |

92.88 |

68.83 |

Lazard (2015)

In November 2015, the investment bank Lazard headquartered in New York, published its ninth annual study on the current electricity production costs of photovoltaics in the US compared to conventional power generators. The best large-scale photovoltaic power plants can produce electricity at 50 USD per MWh. The upper limit at 60 USD per MWh. In comparison, coal-fired plants are between 65 USD and $150 per MWh, nuclear power at 97 USD per MWh. Small photovoltaic power plants on roofs of houses are still at 184–300 USD per MWh, but which can do without electricity transport costs. Onshore wind turbines are 32–77 USD per MWh. One drawback is the intermittency of solar and wind power. The study suggests a solution in batteries as a storage, but these are still expensive so far.[72][73]

Lazard's long standing Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) report is widely considered and industry benchmark. In 2015 Lazard published its inaugural Levelized Cost of Storage (LCOS) report, which was developed by the investment bank Lazard in collaboration with the energy consulting firm, Enovation.[74]

Below is the complete list of LCOEs by source from the investment bank Lazard.[72]

| Plant Type ( USD/MWh) |

Low |

High |

|---|---|---|

| Solar PV-Rooftop Residential |

184 |

300 |

| Solar PV-Rooftop C&I |

109 |

193 |

| Solar PV-Crystalline Utility Scale |

58 |

70 |

| Solar PV-Thin Film Utility Scale |

50 |

60 |

| Solar Thermal with Storage |

119 |

181 |

| Fuel Cell |

106 |

167 |

| Microturbine |

79 |

89 |

| Geothermal |

82 |

117 |

| Biomass Direct |

82 |

110 |

| Wind |

32 |

77 |

| Energy Efficiency |

0 |

50 |

| Battery Storage |

** |

** |

| Diesel Reciprocating Engine |

212 |

281 |

| Natural Gas Reciprocating Engine |

68 |

101 |

| Gas Peaking |

165 |

218 |

| IGCC |

96 |

183 |

| Nuclear |

97 |

136 |

| Coal |

65 |

150 |

| Gas Combined Cycle |

52 |

78 |

NOTE: ** Battery Storage is no longer include in this report (2015). It has been rolled into its own separate report LCOS 1.0, developed in consultation with Enovation Partners (See charts below).

Below are the LCOSs for different battery technologies. This category has traditionally been filled by Diesel Engines. These are "Behind the meter" applications.[75]

| Purpose |

Type |

Low ($/MWh) |

High ($/MWh) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MicroGrid |

Flow Battery |

429 |

1046 |

| MicroGrid |

Lead-Acid |

433 |

946 |

| MicroGrid |

Lithium-Ion |

369 |

562 |

| MicroGrid |

Sodium |

411 |

835 |

| MicroGrid |

Zinc |

319 |

416 |

| Island |

Flow Battery |

593 |

1231 |

| Island |

Lead-Acid |

700 |

1533 |

| Island |

Lithium-Ion |

581 |

870 |

| Island |

Sodium |

663 |

1259 |

| Island |

Zinc |

523 |

677 |

| Commercial and Industrial |

Flow Battery |

349 |

1083 |

| Commercial and Industrial |

Lead-Acid |

529 |

1511 |

| Commercial and Industrial |

Lithium-Ion |

351 |

838 |

| Commercial and Industrial |

Sodium |

444 |

1092 |

| Commercial and Industrial |

Zinc |

310 |

452 |

| Commercial Appliance |

Flow Battery |

974 |

1504 |

| Commercial Appliance |

Lead-Acid |

928 |

2291 |

| Commercial Appliance |

Lithium-Ion |

784 |

1363 |

| Commercial Appliance |

Zinc |

661 |

833 |

| Residential |

Flow Battery |

721 |

1657 |

| Residential |

Lead-Acid |

1101 |

2238 |

| Residential |

Lithium-Ion |

1034 |

1596 |

| All of the above Traditional Method |

Diesel Reciprocating Engine |

212 |

281 |

Below are the LCOSs for different battery technologies. This category has traditionally been filled by Natural Gas Engines. These are "In front of the meter" applications.[75]

| Purpose |

Type |

Low ($/MWh) |

High ($/MWh) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transmission System |

Compressed Air |

192 |

192 |

| Transmission System |

Flow Battery |

290 |

892 |

| Transmission System |

Lead-Acid |

461 |

1429 |

| Transmission System |

Lithium-Ion |

347 |

739 |

| Transmission System |

Pumped Hydro |

188 |

274 |

| Transmission System |

Sodium |

396 |

1079 |

| Transmission System |

Zinc |

230 |

376 |

| Peaker Replacement |

Flow Battery |

248 |

927 |

| Peaker Replacement |

Lead-Acid |

419 |

1247 |

| Peaker Replacement |

Lithium-Ion |

321 |

658 |

| Peaker Replacement |

Sodium |

365 |

948 |

| Peaker Replacement |

Zinc |

221 |

347 |

| Frequency Regulation |

Flywheel |

276 |

989 |

| Frequency Regulation |

Lithium-Ion |

211 |

275 |

| Distribution Services |

Flow Battery |

288 |

923 |

| Distribution Services |

Lead-Acid |

516 |

1692 |

| Distribution Services |

Lithium-Ion |

400 |

789 |

| Distribution Services |

Sodium |

426 |

1129 |

| Distribution Services |

Zinc |

285 |

426 |

| PV Integration |

Flow Battery |

373 |

950 |

| PV Integration |

Lead-Acid |

402 |

1068 |

| PV Integration |

Lithium-Ion |

355 |

686 |

| PV Integration |

Sodium |

379 |

957 |

| PV Integration |

Zinc |

245 |

345 |

| All of the above Traditional Method |

Gas Peaker |

165 |

218 |

Lazard (2016)

On December 15, 2016 Lazard released version 10[76] of their LCOE report and version 2[77] of their LCOS report.

| Type |

Low ($/MWh) |

High ($/MWh) |

|---|---|---|

| Solar PV-Rooftop Residential |

138 |

222 |

| Solar PV-Rooftop C&I |

88 |

193 |

| Solar PV-Community |

78 |

135 |

| Solar PV-Crystalline Utility Scale |

49 |

61 |

| Solar PV-Thin Film Utility Scale |

46 |

56 |

| Solar Thermal Tower with Storage |

119 |

182 |

| Fuel Cell |

106 |

167 |

| Microturbine |

76 |

89 |

| Geothermal |

79 |

117 |

| Biomass Direct |

77 |

110 |

| Wind |

32 |

62 |

| Diesel Reciprocating Engine |

212 |

281 |

| Natural Gas Reciprocating Engine |

68 |

101 |

| Gas Peaking |

165 |

217 |

| IGCC |

94 |

210 |

| Nuclear |

97 |

136 |

| Coal |

60 |

143 |

| Gas Combined Cycle |

48 |

78 |

Lazard (2017)

On November 2, 2017 the investment bank Lazard released version 11[78] of their LCOE report and version 3[79] of their LCOS report.[80]

| Generation Type |

Low ($/MWh) |

High ($/MWh) |

|---|---|---|

| Solar PV - Rooftop Residential |

187 |

319 |

| Solar PV - Rooftop C&I |

85 |

194 |

| Solar PV - Community |

76 |

150 |

| Solar PV - Crystalline Utility Scale |

46 |

53 |

| Solar PV - Thin Film Utility Scale |

43 |

48 |

| Solar Thermal Tower with Storage |

98 |

181 |

| Fuel Cell |

106 |

167 |

| Microturbine |

59 |

89 |

| Geothermal |

77 |

117 |

| Biomass Direct |

55 |

114 |

| Wind |

30 |

60 |

| Diesel Reciprocating Engine |

197 |

281 |

| Natural Gas Reciprocating Engine |

68 |

106 |

| Gas Peaking |

156 |

210 |

| IGCC |

96 |

231 |

| Nuclear |

112 |

183 |

| Coal |

60 |

143 |

| Gas Combined Cycle |

42 |

78 |

Below are the unsubsidized LCOSs for different battery technologies for "Behind the Meter" (BTM) applications.[79]

| Use Case |

Storage Type |

Low ($/MWh) |

High ($/MWh) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial |

Lithium-Ion |

891 |

985 |

| Commercial |

Lead-Acid |

1057 |

1154 |

| Commercial |

Advanced Lead |

950 |

1107 |

| Residential |

Lithium-Ion |

1028 |

1274 |

| Residential |

Lead-Acid |

1160 |

1239 |

| Residential |

Advanced Lead |

1138 |

1188 |

Below are the Unsubsidized LCOSs for different battery technologies "Front of the Meter" (FTM) applications.[79]

| Use Case |

Storage Type |

Low ($/MWh) |

High ($/MWh) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peaker Replacement |

Flow Battery(V) |

209 |

413 |

| Peaker Replacement |

Flow Battery(Zn) |

286 |

315 |

| Peaker Replacement |

Lithium-Ion |

282 |

347 |

| Distribution |

Flow Battery(V) |

184 |

338 |

| Distribution |

Lithium-Ion |

272 |

338 |

| Microgrid |

Flow Battery(V) |

273 |

406 |

| Microgrid |

Lithium-Ion |

383 |

386 |

Note: Flow battery value range estimates

Global

IEA and NEA (2015)

The International Energy Agency and the Nuclear Energy Agency published a joint study in 2015 on LCOE data internationally.[81][82]

Other studies and analysis

Buffett Contract (2015)

In a power purchase agreement in the United States in July 2015 for a period of 20 years of solar power will be paid 3.87 UScent per kilowatt hour (38.7 USD/MWh). The solar system, which produces this solar power, is in Nevada (USA) and has 100 MW capacity.[83]

Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid solar farm (2016)

In the spring of 2016 a winning bid of 2.99 US cents per kilowatt-hour of photovoltaic solar energy was achieved for the next (800 MW capacity) phase of the Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid solar farm in Dubai.[84]

Brookings Institution (2014)

In 2014, the Brookings Institution published The Net Benefits of Low and No-Carbon Electricity Technologies which states, after performing an energy and emissions cost analysis, that "The net benefits of new nuclear, hydro, and natural gas combined cycle plants far outweigh the net benefits of new wind or solar plants", with the most cost effective low carbon power technology being determined to be nuclear power.[85][86]

Brazilian electricity mix: the Renewable and Non-renewable Exergetic Cost (2014)

Exergy costs of Integrated Brazilian Electricity Mix

As long as exergy stands for the useful energy required for an economic activity to be accomplished, it is reasonable to evaluate the cost of the energy on the basis of its exergy content. Besides, as exergy can be considered as measure of the departure of the environmental conditions, it also serves as an indicator of environmental impact, taking into account both the efficiency of supply chain (from primary exergy inputs) and the efficiency of the production processes. In this way, exergoeconomy can be used to rationally distribute the exergy costs and CO

2 emission cost among the products and by-products of a highly integrated Brazilian electricity mix. Based on the thermoeconomy methodologies, some authors[87] have shown that exergoeconomy provides an opportunity to quantify the renewable and non-renewable specific exergy consumption; to properly allocate the associated CO

2 emissions among the streams of a given production route; as well as to determine the overall exergy conversion efficiency of the production processes. Accordingly, the non-renewable unit exergy cost (cNR) [kJ/kJ] is defined as the rate of non-renewable exergy necessary to produce one unit of exergy rate/flow rate of a substance, fuel, electricity, work or heat flow, whereas the Total Unit Exergy Cost (cT) includes the Renewable (cR) and Non-Renewable Unit Exergy Costs. Analogously, the CO

2 emission cost (cCO

2) [gCO

2/kJ] is defined as the rate of CO

2 emitted to obtain one unit of exergy rate/flow rate.[87]

Renewables

Photovoltaics

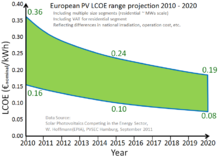

European PV LCOE range projection 2010–2020 (in €-cts/kWh)[88]

Price history of silicon PV cells since 1977

Photovoltaic prices have fallen from $76.67 per watt in 1977 to nearly $0.23 per watt in August 2017, for crystalline silicon solar cells.[89][90] This is seen as evidence supporting Swanson's law, which states that solar cell prices fall 20% for every doubling of cumulative shipments. The famous Moore's law calls for a doubling of transistor count every two years.

By 2011, the price of PV modules per MW had fallen by 60% since 2008, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance estimates, putting solar power for the first time on a competitive footing with the retail price of electricity in some sunny countries; an alternative and consistent price decline figure of 75% from 2007 to 2012 has also been published,[91] though it is unclear whether these figures are specific to the United States or generally global. The levelised cost of electricity (LCOE) from PV is competitive with conventional electricity sources in an expanding list of geographic regions,[7] particularly when the time of generation is included, as electricity is worth more during the day than at night.[92] There has been fierce competition in the supply chain, and further improvements in the levelised cost of energy for solar lie ahead, posing a growing threat to the dominance of fossil fuel generation sources in the next few years.[93] As time progresses, renewable energy technologies generally get cheaper,[94][95] while fossil fuels generally get more expensive:

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

The less solar power costs, the more favorably it compares to conventional power, and the more attractive it becomes to utilities and energy users around the globe. Utility-scale solar power [could in 2011] be delivered in California at prices well below $100/MWh ($0.10/kWh) less than most other peak generators, even those running on low-cost natural gas. Lower solar module costs also stimulate demand from consumer markets where the cost of solar compares very favourably to retail electric rates.[96]

In the year 2015, First Solar agreed to supply solar power at 3.87 cents/kWh levelised price from its 100 MW Playa Solar 2 project which is far cheaper than the electricity sale price from conventional electricity generation plants.[97] From January 2015 through May 2016, records have continued to fall quickly, and solar electricity prices, which have reached levels below 3 cents/kWh, continue to fall.[98] In August 2016, Chile announced a new record low contract price to provide solar power for $29.10 per megawatt-hour (MWh).[99] In September 2016, Abu Dhabi announced a new record breaking bid price, promising to provide solar power for $24.2 per MWh[100] In October 2017, Saudi Arabia announced a further low contract price to provide solar power for $17.90 per MWh.[101]

With a carbon price of $50/ton (which would raise the price of coal-fired power by 5c/kWh), solar PV is cost-competitive in most locations. The declining price of PV has been reflected in rapidly growing installations, totaling a worldwide cumulative capacity of 297 GW by end 2016. According to some estimates total investment in renewables for 2011 exceeded investment in carbon-based electricity generation.[102]

In the case of self consumption, payback time is calculated based on how much electricity is not brought from the grid. Additionally, using PV solar power to charge DC batteries, as used in Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles and Electric Vehicles, leads to greater efficiencies, but higher costs. Traditionally, DC generated electricity from solar PV must be converted to AC for buildings, at an average 10% loss during the conversion. Inverter technology is rapidly improving and current equipment has reached 99% efficiency for small scale residential,[103] while commercial scale three-phase equipment can reach well above 98% efficiency. However, an additional efficiency loss occurs in the transition back to DC for battery driven devices and vehicles, and using various interest rates and energy price changes were calculated to find present values that range from $2,057.13 to $8,213.64 (analysis from 2009).[104]

It is also possible to combine solar PV with other technologies to make hybrid systems, which enable more stand alone systems. The calculation of LCOEs becomes more complex, but can be done by aggregating the costs and the energy produced by each component. As for example, PV and cogen and batteries [105] while reducing energy- and electricity-related greenhouse gas emissions as compared to conventional sources.[106]

Solar thermal

LCOE of solar thermal power with energy storage which can operate round the clock on demand, has fallen to AU$78/MWh (US$61/MWh) in August 2017.[107] Though solar thermal plants with energy storage can work as stand alone systems, combination with solar PV power can deliver further cheaper power.[108] Cheaper and dispatchable solar thermal storage power need not depend on costly or polluting coal/gas/oil/nuclear based power generation for ensuring stable grid operation.[109][110]

When a solar thermal storage plant is forced to idle due to lack of sunlight locally during cloudy days, it is possible to consume the cheap excess infirm power from solar PV, wind and hydro power plants (similar to a lesser efficient, huge capacity and low cost battery storage system) by heating the hot molten salt to higher temperature for converting the stored thermal energy in to electricity during the peak demand hours when the electricity sale price is profitable.[111][112]

Wind power

.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbinner{display:flex;flex-direction:column}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .trow{display:flex;flex-direction:row;clear:left;flex-wrap:wrap;width:100%;box-sizing:border-box}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{margin:1px;float:left}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .theader{clear:both;font-weight:bold;text-align:center;align-self:center;background-color:transparent;width:100%}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbcaption{text-align:left;background-color:transparent}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .text-align-left{text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .text-align-right{text-align:right}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .text-align-center{text-align:center}@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbinner{width:100%!important;box-sizing:border-box;max-width:none!important;align-items:center}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .trow{justify-content:center}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{float:none!important;max-width:100%!important;box-sizing:border-box;text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbcaption{text-align:center}}

NREL projection: the LCOE of U.S. wind power will decline by 25% from 2012 to 2030.[113]

- Current land-based wind

In the windy great plains expanse of the central United States new-construction wind power costs in 2017 are compellingly below costs of continued use of existing coal burning plants. Wind power can be contracted via a power purchase agreement at two cents per kilowatt hour while the operating costs for power generation in existing coal-burning plants remain above three cents.[114]

- Current offshore wind

In 2016 the Norwegian Wind Energy Association (NORWEA) estimated the LCoE of a typical Norwegian wind farm at 44 €/MWh, assuming a weighted average cost of capital of 8% and an annual 3,500 full load hours, i.e. a capacity factor of 40%. NORWEA went on to estimate the LCoE of the 1 GW Fosen Vind onshore wind farm which is expected to be operational by 2020 to be as low as 35 €/MWh to 40 €/MWh.[115] In November 2016, Vattenfall won a tender to develop the Kriegers Flak windpark in the Baltic Sea for 49.9 €/MWh,[116] and similar levels were agreed for the Borssele offshore wind farms. As of 2016, this is the lowest projected price for electricity produced using offshore wind.

- Historic levels

In 2004, wind energy cost a fifth of what it did in the 1980s, and some expected that downward trend to continue as larger multi-megawatt turbines were mass-produced.[117] As of 2012[update] capital costs for wind turbines are substantially lower than 2008–2010 but are still above 2002 levels.[118] A 2011 report from the American Wind Energy Association stated, "Wind's costs have dropped over the past two years, in the range of 5 to 6 cents per kilowatt-hour recently.... about 2 cents cheaper than coal-fired electricity, and more projects were financed through debt arrangements than tax equity structures last year.... winning more mainstream acceptance from Wall Street's banks.... Equipment makers can also deliver products in the same year that they are ordered instead of waiting up to three years as was the case in previous cycles.... 5,600 MW of new installed capacity is under construction in the United States, more than double the number at this point in 2010. 35% of all new power generation built in the United States since 2005 has come from wind, more than new gas and coal plants combined, as power providers are increasingly enticed to wind as a convenient hedge against unpredictable commodity price moves."[119]

This cost has additionally reduced as wind turbine technology has improved. There are now longer and lighter wind turbine blades, improvements in turbine performance and increased power generation efficiency. Also, wind project capital and maintenance costs have continued to decline.[120] For example, the wind industry in the USA in 2014 was able to produce more power at lower cost by using taller wind turbines with longer blades, capturing the faster winds at higher elevations. This opened up new opportunities in Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio. The price of power from wind turbines built 300 to 400 ft (91 to 122 m) above the ground can now compete with conventional fossil fuels like coal. Prices have fallen to about 4 cents per kilowatt-hour in some cases and utilities have been increasing the amount of wind energy in their portfolio, saying it is their cheapest option.[121]

See also

- Electricity pricing

- Comparisons of life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions

- Distributed generation

- Economics of new nuclear power plants

- Demand response

- Intermittent energy source

- National Grid Reserve Service

- Nuclear power in France

- List of thermal power station failures

- Calculating the cost of the UK Transmission network: Estimating cost per kWh of transmission

- List of countries by electricity production from renewable sources

- List of U.S. states by electricity production from renewable sources

- Environmental concerns with electricity generation

- Grid parity

Further reading

Economic Value of U.S. Fossil Fuel Electricity Health Impacts. United States Environmental Protection Agency.

The Hidden Costs of Electricity: Comparing the Hidden Costs of Power Generation Fuels. Civil Society Institute.

Lazard’s Levelized Cost of Energy Analysis – Version 11.0 (Nov. 2017)

References

^ A Review of Electricity Unit Cost Estimates

Working Paper, December 2006 – Updated May 2007 Archived January 8, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

^ "Cost of wind, nuclear and gas powered generation in the UK". Claverton-energy.com. Retrieved 2012-09-04..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "David Millborrows paper on wind costs". Claverton-energy.com. Retrieved 2012-09-04.

^ abcdefghi https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/aeo/assumptions/pdf/table_8.2.pdf

^ Nuclear Energy Agency/International Energy Agency/Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development Projected Costs of Generating Electricity (2005 Update)

^ K. Branker, M. J.M. Pathak, J. M. Pearce, doi:10.1016/j.rser.2011.07.104 A Review of Solar Photovoltaic Levelized Cost of Electricity, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 15, pp.4470–4482 (2011). Open access

^ abcd Branker, K.; Pathak, M.J.M.; Pearce, J.M. (2011). "A Review of Solar Photovoltaic Levelized Cost of Electricity". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 15 (9): 4470–4482. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2011.07.104.

Open access

^ Comparing the Costs of Intermittent and Dispatchable Electricity-Generating Technologies", by Paul Joskow, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, September 2011

^ abcd Bronski, Peter (29 May 2014). "You Down With LCOE? Maybe You, But Not Me:Leaving behind the limitations of levelized cost of energy for a better energy metric". RMI Outlet. Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI). Archived from the original on 28 October 2016. Retrieved 28 October 2016.Desirable shifts in how we as a nation and as individual consumers—whether a residential home or commercial real estate property—manage, produce, and consume electricity can actually make LCOE numbers look worse, not better. This is particularly true when considering the influence of energy efficiency...If you’re planning a new, big central power plant, you want to get the best value (i.e., lowest LCOE) possible. For the cost of any given power-generating asset, that comes through maximizing the number of kWh it cranks out over its economic lifetime, which runs exactly counter to the highly cost-effective energy efficiency that has been a driving force behind the country’s flat and even declining electricity demand. On the flip side, planning new big, central power plants without taking continued energy efficiency gains (of which there’s no shortage of opportunity—the February 2014 UNEP Finance Initiative report Commercial Real Estate: Unlocking the energy efficiency retrofit investment opportunity identified a $231–$300 billion annual market by 2020) into account risks overestimating the number of kWh we’d need from them and thus lowballing their LCOE... If I’m a homeowner or business considering purchasing rooftop solar outright, do I care more about the per-unit value (LCOE) or my total out of pocket (lifetime system cost)?...The per-unit value is less important than the thing considered as a whole...LCOE, for example, fails to take into account the time of day during which an asset can produce power, where it can be installed on the grid, and its carbon intensity, among many other variables. That’s why, in addition to [levelized avoided cost of energy (LACE)], utilities and other electricity system stakeholders...have used benefit/cost calculations and/or an asset’s capacity value or contribution to peak on a system or circuit level.

^ US Energy Information Administration, Levelized cost of new generation resources, 28 January 2013.

^ ab "U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) – Source". Retrieved 25 November 2016.

^ "Marginal Energy Price Analyses". Energy Efficiency Standards (DOE).

^ ab "Subsidies and costs of EU energy. Project number: DESNL14583" Pages: 52. EcoFys, 10 October 2014. Accessed: 20 October 2014. Size: 70 pages in 2MB.

^ International Energy Outlook: Electricity "Although coal-fired generation increases by an annual average of only 1.9 percent, it remains the largest source of electricity generation through 2035. In 2008, coal-fired generation accounted for 40 percent of world electricity supply; in 2035, its share decreases to 37 percent, as renewables, natural gas, and nuclear power all are expected to advance strongly during the projection and displace the need for coal-fired-generation in many parts of the world. World net coal-fired generation grows by 67 percent, from 7.7 trillion kilowatthours in 2008 to 12.9 trillion kilowatthours in 2035." Archived August 22, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

^ "BBC NEWS – Business – The economic impact of global warming". 2002-10-14. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

^ O'Loughlin, Toni (27 October 2009). "Climate change threatens Australia's coastal lifestyle, report warns". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

^ Tufts Civil Engineer Predicts Boston’s Rising Sea Levels Could Cause Billions Of Dollars In Damage

^ Rising Sea Levels' cost on Boston

^ "Tufts University slide 28, note projected Bangladesh evacuation". Retrieved 25 November 2016.

^ "The Hidden Costs of Fossil Fuels". Retrieved 25 November 2016.

^ "Climate Change Effects – Rising Sea Level in depth". Archived from the original on 21 September 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

^ "Short Sharp Science: Five nations under threat from climate change". Retrieved 25 November 2016.

^ "BBC News – ASIA-PACIFIC – Tiny Pacific nation takes on Australia". 2002-03-04. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

^ Boom, Keely. "See you in court: the rising tide of international climate litigation". Retrieved 25 November 2016.

^ New research reveals the real costs of electricity in Europe

^ ExternE-Pol, External costs of current and advanced electricity systems, associated with emissions from the operation of power plants and with the rest of the energy chain, final technical report. See figure 9, 9b and figure 11

^ IPCC, Glossary A-D: "Climate price", in IPCC AR4 SYR 2007.

^ Viktor Wesselak, Thomas Schabbach, Thomas Link, Joachim Fischer: Regenerative Energietechnik. Springer 2013,

ISBN 978-3-642-24165-9, p. 27.

^ Publications: Vienna Convention on Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage. International Atomic Energy Agency.

^ Nuclear Power's Role in Generating Electricity Congressional Budget Office, May 2008.

^ Availability of Dam Insurance Archived 2016-01-08 at the Wayback Machine 1999

^ Methodenkonvention 2.0 zur Schätzung von Umweltkosten B, Anhang B: Best-Practice-Kostensätze für Luftschadstoffe, Verkehr, Strom -und Wärmeerzeugung (PDF; 886 kB). Studie des Umweltbundesamtes (2012). Abgerufen am 23. Oktober 2013.

^ Ökonomische Bewertung von Umweltschäden METHODENKONVENTION 2.0 ZUR SCHÄTZUNG VON UMWELTKOSTEN (PDF; 799 kB), S. 27–29. Studie des Umweltbundesamtes (2012). Abgerufen am 23. Oktober 2013.

^ Externe Kosten der Atomenergie und Reformvorschläge zum Atomhaftungsrecht (PDF; 862 kB), 9/2012. Forum Ökologisch-Soziale Marktwirtschaft e.V. im Auftrag von Greenpeace Energy eG und dem Bundesverband Windenergie e.V. Abgerufen am 23. Oktober 2013.

^ "New Harvard Study Examines Cost of Coal". Environment.harvard.edu. 2011-02-17. Retrieved 2012-09-04.

^ "Levelized Cost of Energy and Levelized Cost of Storage 2018". November 8, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

^ "Tumbling Costs for Wind, Solar, Batteries Are Squeezing Fossil Fuels". London and New York: Bloomberg New Energy Finance. March 28, 2018. Retrieved July 28, 2018.Latest BNEF study of comparative costs worldwide shows an 18% improvement in the competitiveness of onshore wind and solar in the last year, and new and rapidly developing roles for batteries.

^ "Solar and wind now the cheapest power source says BloombergNEF". London and New York. 1 September 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

^ Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2017. Abu Dhabi: International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). January 2018. ISBN 978-92-9260-040-2. Retrieved June 14, 2018.The trend is clear: by 2020, all mainstream renewable power generation technologies can be expected to provide average costs at the lower end of the fossil-fuel cost range. In addition, several solar PV and wind power projects will provide some of the lowest-cost electricity from any source.

^ "EBRD says renewables are now cheapest energy source". October 2018.

^ CIVIL SOCIETY TOWNHALL 2018. October 2018.

^ "The Australian Energy Technology Assessment (AETA) 2012". Office of the Chief Economist. Bureau of Resources and Energy Economics (BREE). Retrieved 28 October 2016.

^ ab The Climate Council The global renewable energy boom: how Australia is missing out, 2014

^ ab http://www.occitanie.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/5-couts_des_enr_22-11-2017.pdf

^ "One simple chart shows why an energy revolution is coming — and who is likely to come out on top". Business Insider France (in French). Retrieved 2018-10-17.

^ abc "Studie: Stromgestehungskosten erneuerbare Energien - März 2018". Fraunhofer ISE. 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

^ ab "Levelized cost of electricity renewable energy technologies" (PDF). Fraunhofer ISE. 2013. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

^ Johnston, Eric, "Son's quest for sun, wind has nuclear interests wary", Japan Times, 12 July 2011, p. 3.

^ Bird, Winifred, "Powering Japan's future", Japan Times, 24 July 2011, p. 7.

^ Johnston, Eric, "Current nuclear debate to set nation's course for decades", Japan Times, 23 September 2011, p. 1.[dead link]

^ "Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders in Scotland report" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-09-04.

^ "Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders in Scotland data". Iesisenergy.org. Retrieved 2012-09-04.

^ Electricity Market Reform – Delivery Plan Department of Energy and Climate Change, December 2013

^ Carsten Volkery: Kooperation mit China: Großbritannien baut erstes Atomkraftwerk seit Jahrzehnten, In: Spiegel Online vom 21. Oktober 2013.

^ "ELECTRICITY GENERATION COSTS" (PDF). www.gov.uk. BEIS. November 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

^ "UK nuclear power plant gets go-ahead". BBC News. 21 October 2013.

^ Roland Gribben and Denise Roland (21 October 2013). "Hinkley Point nuclear power plant to create 25,000 jobs, says Cameron". London: Daily Telegraph.

^ "U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) – Source". www.eia.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-02.

^ "New Report: Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Will Grow, Provide Options for Clean Power Plan Compliance Based on Cost Competitiveness—Official Projections Fail to Capture Market Realities, Skewing Policy Considerations". PR newswire. 22 June 2015.

^ abc US Energy Information Administration, Levelized cost and levelized avoided cost of new generation resources in the Annual Energy Outlook 2015, 14 April 2015

^ US Energy Information Administration, 2016 Levelized cost of new generation resources in the Annual Energy Outlook 2010, 26 April 2010

^ US Energy Information Administration, Levelized cost of new generation resources in the Annual Energy Outlook 2011, 26 April 2011

^ US Energy Information Administration, Levelized cost of new generation resources in the Annual Energy Outlook 2012, 12 July 2012

^ US Energy Information Administration, Levelized cost of new generation resources in the Annual Energy Outlook 2013, 28 January 2013

^ US Energy Information Administration, Levelized cost and levelized avoided cost of new generation resources in the Annual Energy Outlook 2014, 17 April 2014

^ Levelized cost and levelized avoided cost of new generation resources, US Energy Information Administration, Annual Energy Audit 2016, 5 August 2016.

^ Levelized cost and levelized avoided cost of new generation resources, US Energy Information Administration, Annual Energy Outlook 2017, April 2017.

^ Levelized cost and levelized avoided cost of new generation resources, US Energy Information Administration, Annual Energy Outlook 2018, March 2018.

^ Levelized cost and levelized avoided cost of new generation resources, US Energy Information Administration, Annual Energy Outlook 2018, March 2018.

^ OpenEI Transparent Cost Database. Accessed 06/19/2015.

^ http://www.energy.ca.gov/2014publications/CEC-200-2014-003/CEC-200-2014-003-SF.pdf

^ ab [1] November 2014

^ Solar and Wind Outshine Fossil Fuels November 2014

^ "Lazard Press Release" (PDF). Lazard. 2016-12-16. Retrieved 2017-11-06.

^ ab https://www.lazard.com/media/2391/lazards-levelized-cost-of-storage-analysis-10.pdf

^ https://www.lazard.com/media/438038/levelized-cost-of-energy-v100.pdf

^ https://www.lazard.com/media/438042/lazard-levelized-cost-of-storage-v20.pdf

^ "Lazard's Levelized Cost of Energy Analysis - Version 11.0" (PDF). Lazard. 2017-11-02. Retrieved 2017-11-04.

^ abc "Lazard's Levelized Cost of Storage Analysis - Version 3.0" (PDF). Lazard. 2017-11-02. Retrieved 2017-11-04.

^ "Lazard Press Release November 2, 2017" (PDF). Lazard. 2017-11-02. Retrieved 2017-11-04.

^

IEA and NEA (2015). Projected costs of generating electricity: 2015 edition — Executive summary (PDF). Paris, France: International Energy Agency (IEA), Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA), and Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Retrieved 2016-11-08.CS1 maint: Uses authors parameter (link)

^

IEA and NEA (2015). Projected costs of generating electricity: 2015 edition. Paris, France: International Energy Agency (IEA), Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA), and Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). ISBN 978-92-64-24443-6.CS1 maint: Uses authors parameter (link)

^ Buffett strikes cheapest electricity price in US with Nevada solar farm July 2015

^ "MESIA und DEWA melden Rekordgebot bei Photovoltaik-Ausschreibung: 0,0299 USD/kWh Solarstrom" (in German). solarserver.de. 2016-05-01. p. 1. Retrieved 2016-05-11.

^ "Sun, wind and drain". The Economist. 26 July 2014. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

^ THE NET BENEFITS OF LOW AND NO-CARBON ELECTRICITY TECHNOLOGIES. MAY 2014, Charles Frank PDF Archived August 14, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

^ ab Flórez-Orrego, Daniel; Silva, Julio A.M.; Oliveira Jr, Silvio de (2014). "Renewable and non-renewable exergy cost and specific CO

2 emission of electricity generation: The Brazilian case". Energy Conversion and Management. 85: 619–629. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2014.04.058.

^ "Solar Photovoltaics Competing in the Energy Sector—On the road to competitiveness" (PDF). European Photovoltaic Industry Association. September 2011. p. 18. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 26, 2013. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

^ "Price Quotes". Retrieved 23 August 2017.

^ "Sunny Uplands: Alternative energy will no longer be alternative". The Economist. 21 November 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-28.

^ Ken Wells (October 25, 2012), "Solar Energy Is Ready. The U.S. Isn't", Bloomberg Businessweek, businessweek.com, retrieved November 1, 2012

^ "Utilities' Honest Assessment of Solar in the Electricity Supply". Retrieved 25 November 2016.

^ "Renewables Investment Breaks Records". Renewable Energy World. 29 August 2011.

^ Renewable energy costs drop in '09 Reuters, November 23, 2009.

^ Solar Power 50% Cheaper By Year End – Analysis Reuters, November 24, 2009.

^ Arno Harris (31 August 2011). "A Silver Lining in Declining Solar Prices". Renewable Energy World.

^ "NV Energy buys utility-scale solar at record low price under 4 cents/kWh". Retrieved 23 July 2015.

^ New Record Set for World's Cheapest Solar, Now Undercutting Coal (2.99 cents/kWh United Arab Emirates, easily besting coal, which came in at 4.501 cents per kilowatt-hour under a 25-year power purchase agreement, with chart of solar prices in 2015 to May, 2016)

^ EcoWatch (22 August 2016). "Great news!". Retrieved 25 November 2016.

^ "UPDATE – Abu Dhabi confirms USD 24.2/MWh bid in solar tender – SeeNews Renewables". Retrieved 25 November 2016.