Dew point

| Humidity and hygrometry | |

|---|---|

| |

| Specific concepts | |

| |

| General concepts | |

| |

| Measures and Instruments | |

| |

The dew point is the temperature to which air must be cooled to become saturated with water vapour. When further cooled, the airborne water vapor will condense to form liquid water (dew). When air cools to its dew point through contact with a surface that is colder than the air, water will condense on the surface.[1][2] When the temperature is below the freezing point of water, the dew point is called the frost point, as frost is formed rather than dew.[3] The measurement of the dew point is related to humidity. A higher dew point means there will be more moisture in the air.[2]

Contents

1 Humidity

2 Relationship to human comfort

3 Measurement

4 Extreme values

5 Calculating the dew point

5.1 Simple approximation

6 Frost point

7 See also

8 References

9 External links

Humidity

If all the other factors influencing humidity remain constant, at ground level the relative humidity rises as the temperature falls. This is because less vapor is needed to saturate the air, so vapor condenses as the temperature falls. In normal conditions, the dew point temperature will not be greater than the air temperature because relative humidity cannot exceed 100%.[4]

In technical terms, the dew point is the temperature at which the water vapor in a sample of air at constant barometric pressure condenses into liquid water at the same rate at which it evaporates.[5] At temperatures below the dew point, the rate of condensation will be greater than that of evaporation, forming more liquid water. The condensed water is called dew when it forms on a solid surface, or frost if it freezes. The condensed water is called either fog or a cloud, depending on its altitude, when it forms in the air. If the temperature is below the dew point, the vapor is called supersaturated. This can happen if there are not enough particles in the air to act as condensation nuclei.[6]

A high relative humidity implies that the dew point is closer to the current air temperature. A relative humidity of 100% indicates the dew point is equal to the current temperature and that the air is maximally saturated with water. When the moisture content remains constant and temperature increases, relative humidity decreases, but the dew point remains constant.[7]

General aviation pilots use dew point data to calculate the likelihood of carburetor icing and fog, and to estimate the height of a cumuliform cloud base.

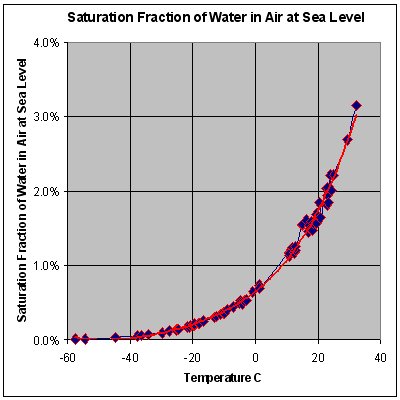

This graph shows the maximum percentage, by mass, of water vapor that air at sea-level pressure across a range of temperatures can contain. For a lower ambient pressure, a curve has to be drawn above the current curve. A higher ambient pressure yields a curve under the current curve.

Increasing the barometric pressure increases the dew point.[8] This means that, if the pressure increases, the mass of water vapour in the air must be reduced in order to maintain the same dew point. For example, consider New York (33 ft or 10 m elevation) and Denver (5,280 ft or 1,610 m elevation[9]). Because Denver is at a higher elevation than New York, it will tend to have a lower barometric pressure. This means that if the dew point and temperature in both cities are the same, the amount of water vapor in the air will be greater in Denver.

Relationship to human comfort

When the air temperature is high, the human body uses the evaporation of sweat to cool down, with the cooling effect directly related to how fast the perspiration evaporates. The rate at which perspiration can evaporate depends on how much moisture is in the air and how much moisture the air can hold. If the air is already saturated with moisture, perspiration will not evaporate. The body's thermoregulation will produce perspiration in an effort to keep the body at its normal temperature even when the rate it is producing sweat exceeds the evaporation rate, so one can become coated with sweat on humid days even without generating additional body heat (such as by exercising).

As the air surrounding one's body is warmed by body heat, it will rise and be replaced with other air. If air is moved away from one's body with a natural breeze or a fan, sweat will evaporate faster, making perspiration more effective at cooling the body. The more unevaporated perspiration, the greater the discomfort.

A wet bulb thermometer also uses evaporative cooling, so it provides a good measure for use in evaluating comfort level.

Discomfort also exists when the dew point is low (below around −30 °C or −22 °F).[citation needed] The drier air can cause skin to crack and become irritated more easily. It will also dry out the airways. The US Occupational Safety and Health Administration recommends indoor air be maintained at 20–24.5 °C (68–76 °F) with a 20–60% relative humidity, equivalent to a dew point of −4.5 to 15.5 °C (24 to 60 °F).[citation needed]

Lower dew points, less than 10 °C (50 °F), correlate with lower ambient temperatures and the body requires less cooling. A lower dew point can go along with a high temperature only at extremely low relative humidity, allowing for relatively effective cooling.

People inhabiting tropical and subtropical climates acclimatize somewhat to higher dew points. Thus, a resident of Singapore or Miami, for example, might have a higher threshold for discomfort than a resident of a temperate climate like London or Chicago. People accustomed to temperate climates often begin to feel uncomfortable when the dew point gets above 15 °C (59 °F), while others might find dew points up to 18 °C (64 °F) comfortable. Most inhabitants of temperate areas will consider dew points above 21 °C (70 °F) oppressive and tropical-like, while inhabitants of hot and humid areas may not find this uncomfortable. Thermal comfort depends not just on physical environmental factors, but also on psychological factors.[10]

Dew point

Relative humidity at 32 °C (90 °F)

Over 26 °C

Over 80 °F

73% and higher

24–26 °C

75–80 °F

62–72%

21–24 °C

70–74 °F

52–61%

18–21 °C

65–69 °F

44–51%

16–18 °C

60–64 °F

37–43%

13–16 °C

55–59 °F

31–36%

10–12 °C

50–54 °F

26–30%

Under 10 °C

Under 50 °F

25% and lower

Measurement

Devices called hygrometers are used to measure dew point over a wide range of temperatures. These devices consist of a polished metal mirror which is cooled as air is passed over it. The temperature at which dew forms is, by definition, the dew point. Manual devices of this sort can be used to calibrate other types of humidity sensors, and automatic sensors may be used in a control loop with a humidifier or dehumidifier to control the dew point of the air in a building or in a smaller space for a manufacturing process.

Extreme values

A dew point of 33 °C (91 °F) was observed at 14:00 EDT on July 12, 1987, in Melbourne, Florida. A dew point of 32 °C (90 °F) has been observed in the United States on at least two other occasions: Appleton, Wisconsin, at 17:00 CDT on July 13, 1995, and New Orleans Naval Air Station at 17:00 CDT on July 30, 1987. A dew point of 35 °C (95 °F) was observed at Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, at 15:00 AST on July 8, 2003, which caused the heat index to reach 81 °C (178 °F), the highest value recorded.

Calculating the dew point

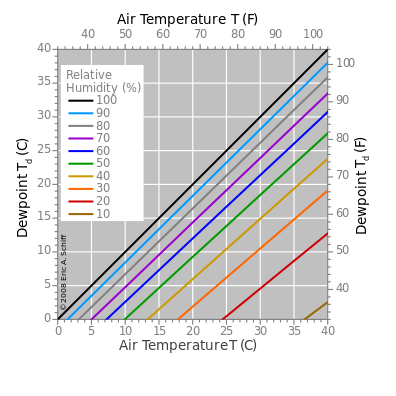

Graph of the dependence of the dew point upon air temperature for several levels of relative humidity.

A well-known approximation used to calculate the dew point, Tdp, given just the actual ("dry bulb") air temperature, T (in degrees Celsius) and relative humidity (in percent), RH, is the Magnus formula:

- γ(T,RH)=ln(RH100)+bTc+T;Tdp=cγ(T,RH)b−γ(T,RH);{displaystyle {begin{aligned}gamma (T,mathrm {RH} )&=ln left({frac {mathrm {RH} }{100}}right)+{frac {bT}{c+T}};\[8pt]T_{mathrm {dp} }&={frac {cgamma (T,mathrm {RH} )}{b-gamma (T,mathrm {RH} )}};end{aligned}}}

The more complete formulation and origin of this approximation involves the interrelated saturated water vapor pressure (in units of millibars, also called hectopascals) at T, Ps(T), and the actual vapor pressure (also in units of millibars), Pa(T), which can be either found with RH or approximated with the barometric pressure (in millibars), BPmb, and "wet-bulb" temperature, Tw is (unless declared otherwise, all temperatures are expressed in degrees Celsius):

- Ps(T)=100RHPa(T)=aebTc+T;Pa(T)=RH100Ps(T)=aeγ(T,RH)≈Ps(Tw)−BPmb0.00066(1+0.00115Tw)(T−Tw);Tdp=clnPa(T)ab−lnPa(T)a;{displaystyle {begin{aligned}P_{mathrm {s} }(T)&={frac {100}{mathrm {RH} }}P_{mathrm {a} }(T)=ae^{frac {bT}{c+T}};\[8pt]P_{mathrm {a} }(T)&={frac {mathrm {RH} }{100}}P_{mathrm {s} }(T)=ae^{gamma (T,mathrm {RH} )}\&approx P_{mathrm {s} }(T_{mathrm {w} })-BP_{mathrm {mb} }0.00066left(1+0.00115T_{mathrm {w} }right)left(T-T_{mathrm {w} }right);\[8pt]T_{mathrm {dp} }&={frac {cln {frac {P_{mathrm {a} }(T)}{a}}}{b-ln {frac {P_{mathrm {a} }(T)}{a}}}};end{aligned}}}

For greater accuracy, Ps(T) (and therefore γ(T, RH)) can be enhanced, using part of the Bögel modification, also known as the Arden Buck equation, which adds a fourth constant d:

- Ps,m(T)=ae(b−Td)(Tc+T);γm(T,RH)=ln(RH100e(b−Td)(Tc+T));Tdp=cγm(T,RH)b−γm(T,RH);{displaystyle {begin{aligned}P_{mathrm {s,m} }(T)&=ae^{left(b-{frac {T}{d}}right)left({frac {T}{c+T}}right)};\[8pt]gamma _{mathrm {m} }(T,mathrm {RH} )&=ln left({frac {mathrm {RH} }{100}}e^{left(b-{frac {T}{d}}right)left({frac {T}{c+T}}right)}right);\[8pt]T_{dp}&={frac {cgamma _{m}(T,mathrm {RH} )}{b-gamma _{m}(T,mathrm {RH} )}};end{aligned}}}

where

a = 6.1121 mb, b = 18.678, c = 257.14 °C, d = 234.5 °C.

There are several different constant sets in use. The ones used in NOAA's presentation[11] are taken from a 1980 paper by David Bolton in the Monthly Weather Review:[12]

a = 6.112 mb, b = 17.67, c = 243.5 °C.

These valuations provide a maximum error of 0.1%, for −30 °C ≤ T ≤ 35°C and 1% < RH < 100%.

Also noteworthy is the Sonntag1990,[13]

a = 6.112 mb, b = 17.62, c = 243.12 °C; for −45 °C ≤ T ≤ 60 °C (error ±0.35 °C).

Another common set of values originates from the 1974 Psychrometry and Psychrometric Charts, as presented by Paroscientific,[14]

a = 6.105 mb, b = 17.27, c = 237.7 °C; for 0 °C ≤ T ≤ 60 °C (error ±0.4 °C).

Also, in the Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology,[15] Arden Buck presents several different valuation sets, with different minimum accuracies for different temperature ranges. Two particular sets provide a range of −40 °C to +50 °C between the two, with even greater minimum accuracy than all of the other, above sets (maximum error at extremes of temperature range):

a = 6.1121 mb, b = 17.368, c = 238.88 °C; for 0 °C ≤ T ≤ 50 °C (error ≤ 0.05%).

a = 6.1121 mb, b = 17.966, c = 247.15 °C; for −40 °C ≤ T ≤ 0 °C (error ≤ 0.06%).

Simple approximation

There is also a very simple approximation that allows conversion between the dew point, temperature, and relative humidity. This approach is accurate to within about ±1 °C as long as the relative humidity is above 50%:

- Tdp≈T−100−RH5;RH≈100−5(T−Tdp);{displaystyle {begin{aligned}T_{mathrm {dp} }&approx T-{frac {100-mathrm {RH} }{5}};\[5pt]mathrm {RH} &approx 100-5(T-T_{mathrm {dp} });end{aligned}}}

This can be expressed as a simple rule of thumb:

For every 1 °C difference in the dew point and dry bulb temperatures, the relative humidity decreases by 5%, starting with RH = 100% when the dew point equals the dry bulb temperature.

The derivation of this approach, a discussion of its accuracy, comparisons to other approximations, and more information on the history and applications of the dew point are given in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society.[16]

For temperatures in degrees Fahrenheit, these approximations work out to

- Tdp,∘F≈T∘F−925(100−RH);RH≈100−259(T∘F−Tdp,∘F);{displaystyle {begin{aligned}T_{mathrm {dp,^{circ }F} }&approx T_{mathrm {{}^{circ }F} }-{tfrac {9}{25}}left(100-mathrm {RH} right);\[5pt]mathrm {RH} &approx 100-{tfrac {25}{9}}left(T_{mathrm {{}^{circ }F} }-T_{mathrm {dp,^{circ }F} }right);end{aligned}}}

For example, a relative humidity of 100% means dew point is the same as air temp. For 90% RH, dew point is 3 °F lower than air temperature. For every 10 percent lower, dew point drops 3 °F.

Frost point

The frost point is similar to the dew point in that it is the temperature to which a given parcel of humid air must be cooled, at constant atmospheric pressure, for water vapor to be deposited on a surface as ice crystals without undergoing the liquid phase (compare with sublimation). The frost point for a given parcel of air is always higher than the dew point, as the stronger bonding between water molecules on the surface of ice requires higher temperature to break.[17]

See also

- Bubble point

- Carburetor heat

- Hydrocarbon dew point

- Psychrometrics

- Thermodynamic diagrams

References

^ Glossary - NOAA's National Weather Service

^ ab John M. Wallace; Peter V. Hobbs (24 March 2006). Atmospheric Science: An Introductory Survey. Academic Press. pp. 83–. ISBN 978-0-08-049953-6..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Glossary - NOAA's National Weather Service

^ "Observed Dew Point Temperature". Department of Atmospheric Sciences (DAS) at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

^ Dew Point | Definition of dew point by Merriam-Webster

^ Skilling, Tom (20 July 2011). "Ask Tom why: Is it possible for relative humidity to exceed 100 percent?". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

^ Horstmeyer, Steve (2006-08-15). "Relative Humidity....Relative to What? The Dew Point Temperature...a better approach". Steve Horstmeyer, Meteorologist, WKRC TV, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA. Retrieved 2009-08-20.

^ "Dew Point in Compressed Air – Frequently Asked Questions" (PDF). Vaisala. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

^ "Denver Facts Guide – Today". The City and County of Denver. Archived from the original on February 3, 2007. Retrieved March 19, 2007.

^ Lin, Tzu-Ping (10 February 2009). "Thermal perception, adaptation and attendance in a public square in hot and humid regions" (PDF). Building and Environment. 44 (10): 2017–2026. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

^ Relative Humidity and Dewpoint Temperature from Temperature and Wet-Bulb Temperature

^ Bolton, David (July 1980). "The Computation of Equivalent Potential Temperature" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 108 (7): 1046–1053. Bibcode:1980MWRv..108.1046B. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1980)108<1046:TCOEPT>2.0.CO;2.

^ SHTxx Application Note Dew-point Calculation

^ "MET4 and MET4A Calculation of Dew Point". Archived from the original on May 26, 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

^ Buck, Arden L. (December 1981). "New Equations for Computing Vapor Pressure and Enhancement Factor" (PDF). Journal of Applied Meteorology. 20 (12): 1527–1532. Bibcode:1981JApMe..20.1527B. doi:10.1175/1520-0450(1981)020<1527:NEFCVP>2.0.CO;2.

^ Lawrence, Mark G. (February 2005). "The Relationship between Relative Humidity and the Dewpoint Temperature in Moist Air: A Simple Conversion and Applications". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 86 (2): 225–233. Bibcode:2005BAMS...86..225L. doi:10.1175/BAMS-86-2-225.

^ Haby, Jeff. "Frost point and dew point". Retrieved September 30, 2011.

External links

Often Needed Answers about Temp, Humidity & Dew Point from the sci.geo.meteorology

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}gamma (T,mathrm {RH} )&=ln left({frac {mathrm {RH} }{100}}right)+{frac {bT}{c+T}};\[8pt]T_{mathrm {dp} }&={frac {cgamma (T,mathrm {RH} )}{b-gamma (T,mathrm {RH} )}};end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e172e1a233ea113da9f7a276cdbc1df2a8b5a1f8)

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}P_{mathrm {s} }(T)&={frac {100}{mathrm {RH} }}P_{mathrm {a} }(T)=ae^{frac {bT}{c+T}};\[8pt]P_{mathrm {a} }(T)&={frac {mathrm {RH} }{100}}P_{mathrm {s} }(T)=ae^{gamma (T,mathrm {RH} )}\&approx P_{mathrm {s} }(T_{mathrm {w} })-BP_{mathrm {mb} }0.00066left(1+0.00115T_{mathrm {w} }right)left(T-T_{mathrm {w} }right);\[8pt]T_{mathrm {dp} }&={frac {cln {frac {P_{mathrm {a} }(T)}{a}}}{b-ln {frac {P_{mathrm {a} }(T)}{a}}}};end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2941b6d88978745c3440d6763a592f35f43955e7)

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}P_{mathrm {s,m} }(T)&=ae^{left(b-{frac {T}{d}}right)left({frac {T}{c+T}}right)};\[8pt]gamma _{mathrm {m} }(T,mathrm {RH} )&=ln left({frac {mathrm {RH} }{100}}e^{left(b-{frac {T}{d}}right)left({frac {T}{c+T}}right)}right);\[8pt]T_{dp}&={frac {cgamma _{m}(T,mathrm {RH} )}{b-gamma _{m}(T,mathrm {RH} )}};end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e3ec45d7aeb6794d84b9119136f89efd7056f5e5)

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}T_{mathrm {dp} }&approx T-{frac {100-mathrm {RH} }{5}};\[5pt]mathrm {RH} &approx 100-5(T-T_{mathrm {dp} });end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/aad60925263f7cd19bed98cf8f153d1e1c67de95)

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}T_{mathrm {dp,^{circ }F} }&approx T_{mathrm {{}^{circ }F} }-{tfrac {9}{25}}left(100-mathrm {RH} right);\[5pt]mathrm {RH} &approx 100-{tfrac {25}{9}}left(T_{mathrm {{}^{circ }F} }-T_{mathrm {dp,^{circ }F} }right);end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/072569768b77b9ec273484aa636e058497ef552e)

Comments

Post a Comment