Asset forfeiture

Criminology and penology | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

Theory

| |||

Types of crime

| |||

Penology

| |||

Schools

| |||

Asset forfeiture or asset seizure is a form of confiscation of assets by the state. It typically applies to the alleged proceeds or instruments of crime. This applies, but is not limited, to terrorist activities, drug related crimes, and other criminal and even civil offenses. Some jurisdictions specifically use the term "confiscation" instead of forfeiture. The alleged purpose of asset forfeiture is to disrupt criminal activity by confiscating assets that potentially could have been beneficial to the individual or organization.

Contents

1 Civil and criminal law

2 Canada

3 European Union

4 United Kingdom

5 United Nations Convention against Corruption

6 United States

6.1 History

6.2 Forfeiture of terrorist finances

6.3 Use of forfeited assets

6.4 Notable forfeitures

7 See also

8 References

9 Further reading

10 External links

Civil and criminal law

This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (November 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Legal systems distinguish between criminal and civil proceedings. Criminal prosecutions regulate crimes against society as a whole or against the government. Penalties for conviction of a violation of a criminal law typically includes being sent to prison, jail or some other form of incarceration. Civil litigation involve disputes either between individuals or individuals and the government. At the conclusion of civil litigation one side can be ordered to pay money [damages] to the other side. Courts also have the authority to order one party to do or not do a specific thing in order to resolve civil disputes. Because of the potential for a loss of liberty, defendants in a criminal case will be provided an attorney at public expense if they are unable to pay for their own lawyer. The same is generally not true in civil cases although there are exceptions. In order for an individual to be found guilty of a crime the government has to provide proof beyond a reasonable doubt of the defendant's guilt. There are several different standards of proof in a civil case, the most common is a preponderance of the evidence which is described as anything over fifty percent.[1]

Civil asset forfeiture has been harshly criticized by civil liberties advocates for its greatly reduced standards for conviction, reverse onus, and financial conflicts of interests arising when the law enforcement agencies who decide whether or not to seize assets stand to keep those assets for themselves.[2][3][4][5]

Canada

Part XII.2 of the Criminal Code, a federal statute, provides a national forfeiture régime for property arising from the commission of a designated offence (i.e. most indictable offences), subsequent to conviction. Provision is also made for the use of restraint and management orders to govern such property during the course of a criminal proceeding.[6]

All provinces and territories except Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island and Yukon Territory, have also enacted statutes to provide for similar civil forfeiture régimes.[7][8] These generally provide, on a balance of probabilities basis, for the seizure of property:

- Acquired from the results of unlawful activity

- Is likely to be used to engage in unlawful activity[9]

The Supreme Court of Canada has upheld civil forfeiture laws as a valid exercise of the provincial government power over property and civil rights. The extent to which the Charter of Rights and Freedoms applies to civil forfeiture statutes is still under dispute. To the extent that such laws are applied for a "punitive" purpose, there is case law to suggest that the Charter applies.[10] In cases where evidence has been obtained illegally, courts in Alberta[11] and British Columbia[12] have excluded such evidence.

European Union

In April 2014, the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union enacted Directive 2014/42/EU on the freezing and confiscation of proceeds of crime in the European Union.[13] The directive allows the seizure and confiscation of property without a criminal conviction only under very specific circumstances.[14][15][16][17][18] Article 4 states:

- Member States shall take the necessary measures to enable the confiscation, either in whole or in part, of instrumentalities and proceeds or property the value of which corresponds to such instrumentalities or proceeds, subject to a final conviction for a criminal offence, which may also result from proceedings in absentia.

- Where confiscation on the basis of paragraph 1 is not possible, at least where such impossibility is the result of illness or absconding of the suspected or accused person, Member States shall take the necessary measures to enable the confiscation of instrumentalities and proceeds in cases where criminal proceedings have been initiated regarding a criminal offence which is liable to give rise, directly or indirectly, to economic benefit, and such proceedings could have led to a criminal conviction if the suspected or accused person had been able to stand trial.

United Kingdom

In the UK, asset forfeiture proceedings are initiated under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002. These fall into various types. Firstly there are confiscation proceedings. A confiscation order is a court order made in the Crown Court requiring a convicted defendant to pay a specified amount of money to the state by a specified date. Secondly, there are cash forfeiture proceedings, which take place (in England and Wales) in the Magistrates Court with a right of appeal to the Crown Court, having been brought by either the police or Customs. Thirdly, there are civil recovery proceedings that are brought by the National Crime Agency "NCA". Neither cash forfeiture proceedings nor proceedings for a civil recovery order require a prior criminal conviction.

In Scotland, confiscation proceedings are initiated by the procurator fiscal or Lord Advocate through the Sheriff Court or High Court of Justiciary. Cash forfeiture and civil recovery are brought by the Civil Recovery Unit of the Scottish Government in the Sheriff Court, with appeals to the Court of Session.

United Nations Convention against Corruption

To facilitate international cooperation in confiscation, the United Nations Convention against Corruption encourages state parties to consider taking the necessary measures to allow confiscation of the proceeds of corruption without a criminal conviction in cases in which the offender cannot be prosecuted by reason of death, flight or absence or in other appropriate cases.[19][20]

United States

There are two types of forfeiture (confiscation) cases, criminal and civil. Approximately half of all forfeiture cases practiced today are civil, although many of those are filed in parallel to a related criminal case.[citation needed] In civil forfeiture cases, the US Government sues the item of property, not the person; the owner is effectively a third-party claimant. The burden is on the Government to establish that the property is subject to forfeiture by a "preponderance of the evidence." If it is successful, the owner may yet prevail by establishing an "innocent owner" defense.

Federal civil forfeiture cases usually start with a seizure of property followed by the mailing of a notice of seizure from the seizing agency (generally the DEA or FBI) to the owner. The owner then has 35 days to file a claim with the seizing agency. The owner must file this claim to later protect his property in court. Once the claim is filed with the agency, the U.S. Attorney has 90 days to review the claim and to file a civil complaint in U.S. District Court. The owner then has 35 days to file a judicial claim in court asserting his ownership interest. Within 21 days of filing the judicial claim, the owner must also file an answer denying the allegations in the complaint. Once done, the forfeiture case is fully litigated in court.[21]

In civil cases, the owner need not be judged guilty of any crime; it is possible for the Government to prevail by proving that someone other than the owner used the property to commit a crime (this claim seems outdated and as such would be contradicted by the "innocent owner" defense).[citation needed] In contrast, criminal forfeiture is usually carried out in a sentence following a conviction and is a punitive act against the offender.

The United States Marshals Service is responsible for managing and disposing of properties seized and forfeited by Department of Justice agencies. It currently manages around $2.4 billion worth of property. The United States Treasury Department is responsible for managing and disposing of properties seized by Treasury agencies. The goal of both programs is to maximize the net return from seized property by selling at auctions and to the private sector and then using the property and proceeds to repay victims of crime and, if any funds remain after compensating victims, for law enforcement purposes.

History

Congress has incrementally expanded the government's authority to disrupt and dismantle criminal enterprises and their money laundering activities since the early 1970s. They have done this by enacting various anti-money laundering and forfeiture laws such as the RICO Act of 1970 and the US Patriot Act of 2001. The concepts of asset forfeiture goes back thousands of years and has been recorded throughout history on many different occasions.[22]

In 2015 a number of criminal justice reformers, including Koch family foundations and the ACLU, announced plans to reduce asset forfeiture in the United States due to the disproportionate penalty it places on low-income alleged wrongdoers. The forfeiture of private property often results in the deprivation of the majority of a person's wealth.[23]

Forfeiture of terrorist finances

It is difficult for authorities to track, confiscate, and disrupt terrorist organization finances because they may come from a variety of sources—such as other countries, supporting sympathizers, crime, or legal businesses. Terrorist groups can profit from many crimes—such as black mail, robbery, extortion, fraud, drug trafficking, etc. If discovered and proven terrorist assets, authorities can confiscate property to disrupt terrorist activities. Understanding what constitutes 'terrorist property' is important, because these offenses are widely defined by the 2000 Act as;"

- Property or money that is likely to be used for the purposes of terrorism (including any resources of an organization)

- Proceeds of the commission of acts of terrorism

- Proceeds of acts actually carried out for the purposes of terrorism."[24]

The 2000 Act brought a new system for the forfeiture of terrorist cash. This was modeled on the UK's drug-trafficking cash seizure process and allowed for the seizure of cash for 48 hours by a constable, customs officer or immigration officer if reasonable grounds were found for suspecting that it was intended to be used for terrorism or was terrorist property. An officer who seized the assets or cash could apply to a magistrates' court for an order authorizing its continued detention to give time for further investigation into where it came from. The magistrates' court is generally satisfied on the balance of probabilities that the cash was intended to be used for the purposes of terrorism or was terrorist property, then it could make a forfeiture order.[24]

Use of forfeited assets

The assets that are forfeited for criminal and civil offenses are used "to put more cops on the street," according to former United States President George H. W. Bush.[25] The assets are dispersed among the law enforcement community for things such as paying the attorneys involved in the forfeiture case, police vehicles, meth-lab clean up, and other equipment and furniture.[22]

Notable forfeitures

- In 1965, the United States Supreme Court overturned the seizure of a vehicle by the Government of Pennsylvania in One 1958 Plymouth Sedan v. Pennsylvania seized using illegally obtained evidence.

- In 1996, the Supreme Court in Bennis v. Michigan upheld the seizure of a vehicle as contraband, despite the owner's use of the innocent owner defense.

USA v. $124,700 August 18, 2006 case from the Eighth Circuit Court on civil forfeiture of $124,700- After the Madoff investment scandal had surfaced, Bernard Madoff was ordered to forfeit $170 billion, although it is believed that he did not have anywhere close to that amount. His wife, Ruth, although not charged, agreed to forfeit about $80 million in assets.[26]

- In 2009, Lloyds Bank forfeited $350 million in connection with violations of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) (falsified outgoing wire transfers to persons on U.S. sanctions lists).[27]

- In 2009, Credit Suisse, a Swiss corporation, forfeited $536 million in connection with violations of IEEPA.[28]

- In 2010, Barclays Bank forfeited $298 million in connection with violations of the IEEPA and the Trading with the Enemy Act.[29]

- In 2010, ABN Amro Bank forfeited $500 million in connection with violations of the IEEPA and the Trading with the Enemy Act.[30]

- In 2013, an appellate court overruled the civil forfeiture of Motel Caswell by Boston-area federal prosecutors in United States v. 434 Main Street, Tewksbury, Mass. Despite a number of previous drug crimes committed on the property by outside parties, the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts ruled that the "resolution of the crime problem should not be to simply take [the owner's] Property."[31]

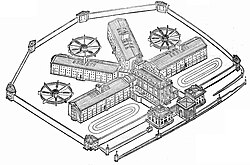

- On April 17, 2014, the State of Texas seized the YFZ Ranch, a one time Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (FLDS) community that housed as many as 700 people when it was raided by Texas on March 29, 2008.[32][33] Under Texas law, authorities can seize property that was used to commit or facilitate certain criminal conduct.[32][33]

See also

- Amercement

- Asset freezing

- Bennis v. Michigan

- Eminent domain

- Equitable sharing

- Forfeiture Endangers American Rights

- Operation Protect Our Children

References

^ "Preponderance of the Evidence". Wex. Cornell Law School. Retrieved 16 December 2017..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "The Forfeiture Racket". Reason.com. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

^ "A truck in the dock". The Economist. May 27, 2010.

^ Kevin Drum (2010-04-07). "Civil Asset Forfeiture". Mother Jones. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

^ Osburn, Judy. "Forfeiture Endangers American Rights". FEAR. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

^ "Criminal Code, RSC 1985, c C-46, Part XII.2". Retrieved 2012-04-29.

^ John Thompson (2010-05-07). "Fighting civil forfeiture". Yukon News. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

^ Joshua Alan Krane (2010). "Forfeited: Civil Forfeiture and the Canadian Constitution" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-04-29.

^ "Civil Forfeiture in Ontario" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-05-14. Retrieved 2012-04-29.

^ "Civil Forfeiture & the Charter - Civil Forfeiture in Canada".

^ "Alberta (Minister of Justice) v Willis, 2015 ABQB 328 – Examination for Discovery Does Not Breach Charter Right to Silence - Civil Forfeiture in Canada".

^ "British Columbia (Director of Civil Forfeiture) v. Huynh, 2013 BCSC 980 – Civil Forfeiture Engages "Exactly the Same Charter Principles" as Criminal Law - Civil Forfeiture in Canada".

^ "EUR-Lex - 32014L0042 - EN - EUR-Lex".

^ Nielsen, Nikolaj (25 February 2014). "EU to donate criminal assets to charity". EUobserver.

^ "European Parliament Passes New EU Rules To Crack Down On Crime Profits". rttnews.com. 25 February 2014.

^ "How seizing criminal assets could leave everyone better off - except criminals". European Parliament. 25 February 2014.

^ "Cecilia Malmström welcomes European Parliament's vote on new EU rules to crack down on crime profits" (Press release). European Commission. 25 February 2014.

^ "Making it easier to confiscate criminal assets EU-wide" (Press release). EPP Group. EurActiv. 25 February 2014.

^ Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on the freezing and confiscation of proceeds of crime in the European Union Archived March 3, 2014, at the Wayback Machine (COM/2012/085) at EUR-Lex

^ United Nations Convention against Corruption § 54(1)(c)

^ 18 United States Code 983(a) & Rule G, Supplemental Rules for Admiralty or Maritime Claims and Asset Forfeiture Actions

^ ab "In Depth: Where the Money Goes: Forfeiture proceeds buy small luxuries, but no slush". Chris D Edoardo & A.D. Hopk. Las Vegas Review–Journal. Las Vegas, Nevada. 1 Apr 2001. p. 27A.

^ Hudetz, Mary (Oct 15, 2015). "Forfeiture reform aligns likes of billionaire Charles Koch, ACLU". The Topeka Capital Journal.

^ ab "The Confiscation, Forfeiture and Disruption of Terrorist Finances". Bell, R.E.. Journal of Money Laundering Control. 7.2 (Autumn 2003): 105–25.

^ http://mediatrackers.org/assets/uploads/2012/07/DCCC2012JudyBiggertIL11-ResearchBook.pdf

^ "Report: Ruth Madoff Agrees To Forfeit $80M". CBS News. June 28, 2009.

^ "Lloyds TSB Bank Plc Agrees to Forfeit $350 Million in Connection with Violations of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act". U.S. Department of Justice. 2009-01-09. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

^ "Credit Suisse Agrees to Forfeit $536 Million in Connection with Violations of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act and New York State Law" (Press release). U.S. Department of Justice. 2009-12-16. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

^ "Barclays Bank PLC Agrees to Forfeit $298 Million in Connection with Violations of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act and the Trading with the Enemy Act" (Press release). U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation. 18 August 2010. Archived from the original on 24 September 2010. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

^ "Former ABN Amro Bank N.V. Agrees to Forfeit $500 Million in Connection with Conspiracy to Defraud the U.S. & with Violation of Bank Secrecy Act". Washington: Financialtaskforce.org. 2010-05-10. Archived from the original on 2010-05-23. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

^ "Triumphant motel owner slams Carmen Ortiz". Boston Herald. 2013-08-07. Retrieved 2013-08-07.

^ ab "Texas Seizes Polygamist Warren Jeffs' Ranch". Eldorado, Texas: NBC. Associated Press. April 17, 2014. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

^ ab Carlisle, Nate (April 17, 2014). "Texas takes possession of polygamous ranch". The Salt Lake Tribune. Eldorado, Texas: MediaNews Group. Retrieved April 17, 2014.

Further reading

Levy, Leonard Williams (1996). A License to Steal: The Forfeiture of Property. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-2242-6.

Stillman, Sarah (2013). "The Use and Abuse of Civil Forfeiture". The New Yorker.

External links

Last Week Tonight on YouTube – John Oliver, October 5, 1014

Introduction to forfeiture laws – Legal Information Institute, Cornell University

List of offenses that trigger federal forfeiture (page 2)

Crime and Forfeiture – Congressional Research Service

South Africa's constitutional safeguards are in tatters – Professor Robert Vivian.

Comments

Post a Comment