Fort Necessity National Battlefield

| Fort Necessity National Battlefield | |

|---|---|

IUCN category III (natural monument or feature)[1] | |

The reconstructed Fort Necessity | |

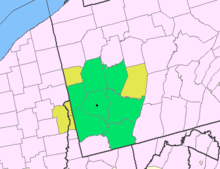

Location of Fort Necessity National Battlefield in Pennsylvania Show map of Pennsylvania  Fort Necessity National Battlefield (the US) Show map of the US | |

| Location | Wharton Township, Fayette, Pennsylvania, United States |

| Coordinates | 39°48′55″N 79°35′22″W / 39.81528°N 79.58944°W / 39.81528; -79.58944Coordinates: 39°48′55″N 79°35′22″W / 39.81528°N 79.58944°W / 39.81528; -79.58944 |

| Area | 902.8 acres (365.4 ha)[2] |

| Elevation | 1,955 ft (596 m) |

| Established | 1931-03-04[2] |

| Website | www.nps.gov/fone/ |

Fort Necessity National Battlefield | |

U.S. National Register of Historic Places | |

| Nearest city | Uniontown |

| NRHP reference # | 66000664[3] |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

Fort Necessity National Battlefield is a National Battlefield Site in Fayette County, Pennsylvania, United States, which preserves the site of the Battle of Fort Necessity. The battle, which took place on July 3, 1754, was an early battle of the French and Indian War, and resulted in the surrender of British colonial forces under Colonel George Washington, to the French and Indians, under Louis Coulon de Villiers.

The site also includes the Mount Washington Tavern, once one of the inns along the National Road, and in two separate units the grave of British General Edward Braddock, killed in 1755, and the site of the Battle of Jumonville Glen.

Contents

1 Battle of Fort Necessity (1754)

2 Park formation and structure

3 Mount Washington Tavern

4 General Braddock's grave site

5 See also

6 References

7 External links

Battle of Fort Necessity (1754)

An engraving depicting the evening council of George Washington at Fort Necessity.

After returning to the great meadows in northwestern Virginia, and what is now Fayette County, Pennsylvania, George Washington decided it prudent to reinforce his position. Supposedly named by Washington as Fort Necessity or Fort of Necessity, the structure protected a storehouse for supplies such as gunpowder, rum, and flour. The crude palisade they erected was built more to defend supplies in the fort's storehouse from Washington's own men, whom he described as "loose and idle", than as a planned defense against a hostile enemy. The sutler of Washington's force was John Fraser, who earlier had been second-in-command at Fort Prince George. Later he served as Chief Scout to General Edward Braddock and then Chief Teamster to the Forbes Expedition.

By June 13, 1754, Washington had under his command 295 colonials and the nominal command of 100 additional regular British army troops from South Carolina. Washington spent the remainder of June 1754 extending the wilderness road further west and down the western slopes of the Allegheny range into the valley of the Monongahela River. He wanted to create a river crossing point roughly 41 mi (66 km) near Redstone Creek and Redstone Old Fort.

This was a prehistoric Native American earthwork mound on a bluff overlooking the river crossing. The aboriginal mound structure may have once been part of a fortification. Five years later in the war, Fort Burd was constructed at Redstone Old Fort. The area eventually became the site of Nemacolin Castle and Brownsville, Pennsylvania—an important western jumping-off point for travelers crossing the Alleghenies in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

To reach the Ohio River basins' navigable waters as soon as possible on the Monongahela River, Washington chose to follow Nemacolin's Trail, a Native American trail which had been somewhat improved by colonists, with Nemacolin's help. He preferred this to following the ridge-hopping, high-altitude path traversed by the western part of the route that was later chosen for Braddock's Road. It jogged to the north near the fort and passed over another notch near Confluence, Pennsylvania into the valley and drainage basin of the Youghiogheny River. The Redstone destination at the terminus of Nemacolin's Trail was a natural choice for an advanced base. The location was one of the few known good crossing points where both sides of the wide deep river had low accessible banks; steep sides were characteristic of the Monongahela River valley.

Late in the day on July 3, Washington did not know the French situation. Believing his situation was impossible, he accepted surrender terms which allowed the peaceful withdrawal of his forces, which he completed on July 4, 1754.[4] The French subsequently occupied the fort and then burned it. Washington did not speak French, and stated later that if he had known that he was confessing to the "assassination" of Joseph Coulon de Jumonville, he would not have signed the surrender document.

An old Postcard of the Mount Washington Tavern.

Park formation and structure

During the Great Depression of the 20th century, attempts to preserve the location of Fort Necessity were undertaken. On March 4, 1931, Congress declared the location a National Battlefield Site under management of the War Department. Transferred to the National Park Service in 1933, the park was redesignated a National Battlefield on August 10, 1961. As with all historic sites administered by the National Park Service, the battlefield was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966.

Subsequent archaeological research helped to uncover the majority of the original fort position, shape and design. A replica of the fort was constructed on site in the 1970s. A new visitor center, which also is home to a National Road interpretive center, opened on October 8, 2005. The battlefield and fort are currently being improved.

Mount Washington Tavern

The Mount Washington Tavern, built as a stagecoach stop for early travelers on the National Road.

On a hillside adjacent to the battlefield and within the boundaries of the park is Mount Washington Tavern, a classic example of the many inns once lining the National Road, the United States' first federally funded highway.

The land on which the tavern was built was originally owned by George Washington. In 1770 he purchased the site on which he had commanded his first battle. Around the 1830s, Judge Nathanial Ewing of Uniontown constructed the tavern. James Sampey acquired the tavern in 1840. It was operated by his family until the railroad construction boom caused the National Road to decline in popularity, rendering the inn unprofitable.

In 1855, it was sold to the Fazenbaker family. They used it as a private home for the next 75 years, until the Commonwealth Of Pennsylvania purchased the property in 1932. In 1961 the National Park Service purchased the property from the state, making the building a part of Fort Necessity. The Mount Washington Tavern demonstrates the standard features of an early American tavern, including a simple barroom that served as a gathering place, a more refined parlor that was used for relaxation, and bedrooms in which numerous people would crowd to catch up on sleep.

General Braddock's grave site

The grave of General Edward Braddock.

Dedication Plaque

In a separate unit of the park, lying about one mile (1.6 km) northwest of the battlefield, is the grave of General Edward Braddock. The British commander led a major expedition to the area in 1755 which included the construction of Braddock's Road, a useful but inadequate wilderness road through western Pennsylvania. Braddock was severely wounded in the Battle of the Monongahela as the British advanced toward Fort Duquesne.

He and his forces fled along the wilderness road to a site near Great Meadows. Braddock died on July 13, 1755, and was buried in an elaborate ceremony officiated by George Washington. He was buried under the road in order to hide the location of his grave from the enemy French and Indians. [5] In 1804 Braddock's remains were discovered by men making repairs to the wilderness road.[citation needed] A marker was erected in 1913.

See also

- Joseph Coulon de Jumonville

- Jumonville

References

^ "Fort Necessity National Battlefield". Protected Planet. IUCN. Retrieved 6 May 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab "Home Page for the Stewardship and Partnerships Team". National Park Service; Philadelphia Support Office. Retrieved 2009-06-30.

^ National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Retrieved 2013-07-16.

^ Leckie, 276

^ Fort Necessity - National Park Service

- Bibliography

Ellis, Joseph J. (2008) [2004]. George Washington: His Excellency. London.

Leckie, Robert (2006). A Few Acres of Snow: The Saga of the French and Indian Wars. Edison, NJ: Castle Books. ISBN 0-7858-2100-7.

Stotz, Charles Morse (2005). Outposts Of The War For Empire: The French And English In Western Pennsylvania: Their Armies, Their Forts, Their People 1749-1764. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 0-8229-4262-3.

External links

National Park Service. "Fort Necessity National Battlefield". U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2006-06-29.

National Park Service. "Battlefield History". Retrieved 2006-06-29.

Fort Necessity & National Battlefield Education & Interpretive Center, Christopher Chadbourne and Associates, Inc. (Exhibit Design)- National Register nomination form

- Map links

- Main unit (Fort Necessity): 39°48′55″N 79°35′22″W / 39.81528°N 79.58944°W / 39.81528; -79.58944

- Braddock Grave unit: 39°49′57″N 79°36′4″W / 39.83250°N 79.60111°W / 39.83250; -79.60111

- Jumonville Glen unit: 39°53′15″N 79°38′38″W / 39.88750°N 79.64389°W / 39.88750; -79.64389

- Main unit (Fort Necessity): 39°48′55″N 79°35′22″W / 39.81528°N 79.58944°W / 39.81528; -79.58944

Comments

Post a Comment