Vladimir-Suzdal

Grand Duchy of Vladimir* Владимиро-Су́здальское кня́жество Vladimiro-Suzdal'skoye knyazhestvo | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1157–1331 | |||||||||

Seal of Alexander Nevsky | |||||||||

Principality of Vladimir-Suzdal (Rostov-Suzdal) within Kievan Rus' in the 11th century | |||||||||

| Status | Vassal state of the Golden Horde (from 1238) | ||||||||

| Capital | Vladimir | ||||||||

| Common languages | Old East Slavic | ||||||||

| Religion | Russian Orthodox Christianity | ||||||||

| Government | Principality | ||||||||

| Grand Duke of Vladimir | |||||||||

• 1157–1175 (first) | Andrey Bogolyubsky | ||||||||

• 1328–1331 (last) | Alexander of Suzdal | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 1157 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1331 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

*Since 1169 after sacking Kiev, the Duchy of Vladimir-Suzdal became the Grand Duchy of Vladimir-Suzdal. | |||||||||

Part of a series on the | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Russia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vladimir-Suzdal (Russian: Владимирско-Су́здальская, Vladimirsko-Suzdal'skaya), also Vladimir-Suzdalian Rus'[1][2] formally known as the Grand Duchy of Vladimir[3] (1157–1331) (Russian: Владимиро-Су́здальское кня́жество, Vladimiro-Suzdal'skoye knyazhestvo; Latin: Volodimeriae[4]), was one of the major principalities that succeeded Kievan Rus' in the late 12th century, centered in Vladimir-on-Klyazma. With time the principality grew into a grand duchy divided into several smaller principalities. After being conquered by the Mongol Empire, the principality became a self-governed state headed by its own nobility. A governorship of principality, however, was prescribed by a Khan declaration (jarlig) issued from the Golden Horde to a noble family of any of smaller principalities.

Vladimir-Suzdal is traditionally perceived as a cradle of the Great Russian language and nationality, and it gradually evolved into the Grand Duchy of Moscow.

Contents

1 Origin

1.1 Rostov principality

1.2 Rostov-Suzdal

2 Rise of Vladimir

3 Mongol yoke

4 Further reading

5 See also

6 References

7 External links

Origin

Rostov principality

The first notable administrators in the Rostov region presumably were the sons of Vladimir the Great, Boris and Gleb, and later Yaroslav the Wise. The principality occupied a vast territory in the northeast of Kievan Rus', approximately bounded by the Volga, Oka, and Northern Dvina rivers. Until the decline of Kievan Rus' in the 12th-13th centuries the territory was also commonly called Zalesie, literally depicting a region beyond woodland. Scarce historical information exists for the area during that time. The foundation of the city of Rostov has been lost in the span of time. According to the archeologist Andrei Leontiev, who specializes in the history of the region, the Rostov land until the 10th century was already under the control of Rostov city, while Sarskoye Gorodishche was a tribal center of the native Merya people.

In the 10th century an eparchy was established in Rostov. One of the first known princes was Yaroslav the Wise and later Boris Vladimirovich. At that time Rostov was the major center of the Eastern Orthodox Christianity in the region dominated mostly by shamanism. Until the 11th century Rostov was often associated with the Great Novgorod. Evidently the spread of Eastern Orthodox Christianity to the lands of the Great Perm was successfully conducted from Rostov. Rostov was the regional capital, including other important towns included Suzdal, Yaroslavl, and Belozersk.

Rostov-Suzdal

Vladimir Monomakh, son of the Grand Prince of Vsevolod I, inherited the rights to the principality in 1093. As the Grand Prince of Kiev he appointed his son George I to rule the northeastern lands and in 1125 moved its capital from Rostov to Suzdal, after which the Principality was referred to as Rostov-Suzdal.[5] During the 11th and 12th centuries when southern parts of Rus' were systematically raided by Turkic nomads, their inhabitants began to migrate northward. In the formerly wooded areas, known as Zalesye, many new settlements were established. The foundations of Pereslavl, Kostroma, Dmitrov, Moscow, Yuriev-Polsky, Uglich, Tver, Dubna, and many others were assigned (either by chronicle or popular legend) to George I, whose sobriquet ("the Long-Armed") alludes to his dexterity in manipulating the politics of far-away Kiev. Sometime in 1108 Monomakh strengthened and rebuilt the town of Vladimir on the Klyazma River, 31 km south of Suzdal. During the rule of George I the principality gained military strength, and in the Suzdal-Ryazan war of 1146 it conquered the Ryazan Principality. Later in the 1150s Yuri occupied Kiev a couple of times as well. From that time the lands of the northeastern Rus' played an important role in the politics of Kievan Rus'.

Rise of Vladimir

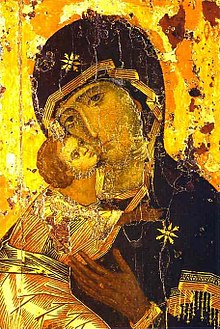

The veneration of the Theotokos as a holy protectress of Vladimir was introduced by Prince Andrew, who dedicated to Her many churches and installed in his palace a revered image, known as Theotokos of Vladimir.

George's son Andrew the Pious significantly increased Vladimir's power at the expense of the nearby princely states, which he treated with contempt. After burning down Kiev, then the metropolitan seat of Rus', in 1169, he enthroned his younger brother. For Andrew, his capital of Vladimir was a far greater concern, as he embellished it with white stone churches and monasteries. Prince Andrew was murdered by boyars in his suburban residence at Bogolyubovo in 1174.

After a brief interregnum, Andrew's brother Vsevolod III secured the throne. He continued most of his brother's policies and once again subjugated Kiev in 1203. Vsevolod's chief enemies, however, were the Southern Ryazan Principality, which appeared to stir discord in the princely family, and the mighty Turkic state of Volga Bulgaria, which bordered Vladimir-Suzdal to the east. After several military campaigns, Ryazan was burnt to the ground, and the Bulgars were forced to pay tribute.

Vsevolod's death in 1212 precipitated a serious dynastic conflict. His eldest son Konstantin gained the support of powerful Rostovan boyars and Mstislav the Bold of Kiev and expelled the lawful heir, his brother George, from Vladimir to Rostov. George managed to return to the capital six years later, upon Konstantin's death. George proved to be a shrewd ruler who decisively defeated Volga Bulgaria and installed his brother Yaroslav in Novgorod. His reign, however, ended when the Mongol hordes under Batu Khan took and burnt Vladimir in 1238. Thereupon they proceeded to devastate other major cities of Vladimir-Suzdal during the Mongol invasion of Kievan Rus'.

Mongol yoke

Assumption Cathedral in Vladimir was built in 1158–1160 and functioned as the mother church of Kievan Rus' in the 13th century.

None of the cities of the principality managed to regain the power of the Great Kievan Rus' after the Mongol invasion. Vladimir became a vassal of the Mongol Empire, later succeeded by the Golden Horde, with the Grand Prince appointed by the Great Khan. Even the popular Alexander Nevsky of Pereslavl had to go to the Khan's capital in Karakorum in order to be installed as the Grand Prince in Vladimir. As many factions strove for power, the principality rapidly disintegrated into eleven tiny states: Moscow, Tver, Pereslavl, Rostov, Yaroslavl, Uglich, Belozersk, Kostroma, Nizhny Novgorod, Starodub-upon-Klyazma, and Yuriev-Polsky. All of them nominally acknowledged the suzerainty of the Grand Prince of Vladimir, but his effective authority became progressively weaker.

By the end of the century, only three cities — Moscow, Tver, and Nizhny Novgorod — still contended for the title of Grand Prince of Vladimir. Once installed, however, they chose to remain in their own cities rather than moving to Vladimir. The Grand Duchy of Moscow gradually came to eclipse its rivals. When the metropolitan of Kievan Rus' moved his chair from Vladimir to Moscow in 1325, it became clear that Moscow had effectively succeeded Vladimir as the chief centre of power in the north-east remnant of Kievan Rus'.

Further reading

- William Craft Brumfield. A History of Russian Architecture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993) .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

ISBN 978-0-521-40333-7 (Chapter Three: "Vladimir and Suzdal Before the Mongol Invasion")

See also

- Zalesye

- List of early East Slavic states

Grand Duke of Vladimir / ru:Список князей Владимирских

- Darughachi

References

^ J., Halperin, Charles (1985). Russia and the Golden Horde : the Mongol impact on medieval Russian history. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 85. ISBN 0253350336. OCLC 11814554.

^ A.),, Buckley, Mary (Mary E. The politics of unfree labour in Russia : human trafficking and labour migration. Cambridge, United Kingdom. p. 34. ISBN 9781108419963. OCLC 992788554.

^ "RUSSIA, Slavic Languages, Orthodox Calendar, Russian Battleships". Friesian.com. Retrieved 2013-07-28.The word in Russian is Knyaz which is different from the word borrowed from German for "duke", gertsog (i.e. herzog), and from Latin for "prince", prints. The problem seems to be that in modern times a brother of the Tsar was always a Velikii Knyaz and this was translated "Grand Duke" by analogy to the tradition of giving the title Duke to the brothers of the Kings of England and France. This ambiguity exists in other regional languages, where either "prince" or "duke" can also translate kníze in Czech, knez in Croatian, ksiaze in Polish, knieza in Slovakian, kunigaikshtis in Lithuanian, and voivode in Hungarian.

^ Introduction into the Latin epigraphy (Введение в латинскую эпиграфику).

^ Yury Dolgoruky in Grand Soviet Encyclopedia

External links

(in Russian) History of Vladimir-Suzdal Principality in the Grand Soviet Encyclopedia

Comments

Post a Comment