History of communism

| Part of a series on |

| Communism |

|---|

|

Concepts

|

Aspects

|

Variants

|

Internationals

|

People

|

By region

|

Related topics

|

The history of communism encompasses a wide variety of ideologies and political movements sharing the core theoretical values of common ownership of wealth, economic enterprise and property.[1]

Most modern forms of communism are grounded at least nominally in Marxism, an ideology conceived by noted sociologist Karl Marx during the mid-19th century.[2] Marxism subsequently gained a widespread following across much of Europe and throughout the late 1800s its militant supporters were instrumental in a number of failed revolutions on that continent.[1] During the same era, there was also a proliferation of communist parties which rejected armed revolution, but embraced the Marxist ideal of collective property and a classless society.[1]

Although Marxist theory suggested that the places ripest for social revolution—either through peaceful transition or by force of arms—were industrial societies, communism was mostly successful in underdeveloped countries with endemic poverty such as the Russian Empire and the Republic of China.[2] In 1917, the Bolshevik Party seized power during the Russian Revolution and created the Soviet Union, the world's first Marxist state.[3] The Bolsheviks thoroughly embraced the concept of proletarian internationalism and world revolution, seeing their struggle as an international rather than a purely regional cause.[3][2] This was to have a phenomenal impact on the spread of communism during the twentieth century as the Soviet Union installed new communist governments in Central and Eastern Europe following World War II and indirectly backed the ascension of others in the Americas, Asia and Africa.[1] Pivotal to this policy was the Communist International (also simply known as the Commintern), which was formed with the perspective of aiding and assisting communist parties around the world and fostering revolution.[3] This was one major cause of tensions during the Cold War as the United States and its military allies equated the global spread of communism with Soviet expansionism by proxy.[4]

By 1985, one-third of the world's population lived under a communist system of government in one form or another.[1] However, there was significant debate among communist ideologues as to whether most of these countries could be meaningfully considered Marxist at all.[4] Many of the basic components of the Marxist system were altered and revised by various self-styled communist regimes.[4] The failure of communist governments to live up to the ideal of a communist society as well as their general trend towards increasing authoritarianism has been linked to the decline of communism in the late 20th century.[1] With the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, several communist states repudiated or abolished the ideology altogether.[5] By the 21st century, only a small number of communist governments remained, namely Cuba, Vietnam and Laos.[1] Despite retaining a nominal commitment to communism, the People's Republic of China has essentially ceased to be governed by the principles of Marxism or Maoism, reverting to an authoritarian regime with a mixed economy.[1]

From the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 until 2017, demographers have estimated that self-styled communist governments have collectively claimed the lives of more than 68 million people through starvation, political purges, extrajudicial killings, forced labour camps, and violently implemented social engineering policies.[6]

Contents

1 History of the word communism

2 Early development (1840–1916)

2.1 Pre-Marxist communism

2.2 Karl Marx

2.3 Early development of Marxism

3 International communism: periodization

4 The early Communist states (1917–1944)

4.1 The Russian Revolution and the formation of the Soviet Union

4.2 Comintern, Mongolia and the communist uprisings in Europe

4.3 Front organisations

4.4 Stalinism in the Soviet Union

4.4.1 The Great Terror

4.5 Pre-war dissident communisms

5 Spreading communism (1945–1957)

5.1 Soviet Union

5.2 Eastern Europe

5.2.1 Hungarian Revolution of 1956

5.2.2 Prague Spring 1968

5.3 West Germany

5.4 China's Great Leap Forward

5.5 Early post-war dissident communisms

6 The Cold War and revisionism (1958–1979)

6.1 Maoism and the Cultural Revolution in China

6.2 The Cuban Revolution

6.3 African Communism

6.4 Eurocommunism

7 The collapse of the Communist Powers (1980–1992)

8 Contemporary communism (1993–present)

9 Sources

10 Further reading

10.1 Primary sources

11 External links

History of the word communism

Portrait of Victor d'Hupay (c. 1790) first theorician and founder of modern communism

"Communism" derives from the French communisme which developed out of the Latin roots communis and the suffix isme – and was in use as a word designating various social situations before it came to be associated with more modern conceptions of an economic and political organization. Semantically, communis can be translated to "of or for the community" while isme is a suffix that indicates the abstraction into a state, condition, action or doctrine, so "communism" may be interpreted as "the state of being of or for the community". This semantic constitution has led to various usages of the word in its evolution, but ultimately came to be most closely associated with Marxism, most specifically embodied in The Communist Manifesto, which proposed a particular type of communism.

The term was first created in its modern definition by the French philosopher Victor d'Hupay. In his 1777 book Projet de communauté philosophe, d'Hupay pushes the legacy of the Enlightenments to principles which he lived up to during most of his life in his bastide of Fuveau, Provence.[7] His book can be seen as a backbone of communist philosophy as d'Hupay attempts a definition of this lifestyle which he calls a "commune" and advises to "share all economic and material products between inhabitants of the commune, so that all may benefit from each other's work".[8] His friend and contemporary author Restif de la Bretonne also describes him as a "communist" in one of his books.[9]

Early development (1840–1916)

Pre-Marxist communism

Many historical groups have been considered as following forms of communism. Karl Marx and other early communist theorists believed that hunter-gatherer societies as were found in the Paleolithic were essentially egalitarian and he therefore termed their ideology to be "primitive communism". Early Christianity supported a form of common ownership based on the teachings in the New Testament which emphasised sharing amongst everyone. Other ancient Jewish sects, like the Essenes, also supported egalitarianism and communal living.[10]

In Europe, during the early modern period various groups supporting communist ideas appeared. Tommaso Campanella's 1601 work The City of the Sun propagated the concept of a society where the products of society should be shared equally.[11] Within a few centuries, during the English Civil War various groups on the side of the Roundheads propagated the redistribution of wealth on an egalitarian basis, namely the Levellers and the Diggers.[12] In the 18th century, the French philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau in his hugely influential The Social Contract (1762) outlined the basis for a political order based on popular sovereignty rather than the rule of monarchs.[13] His views proved influential during the French Revolution of 1789 in which various anti-monarchists, particularly the Jacobins, supported the idea of redistributing wealth equally among the people, including Jean-Paul Marat and Gracchus Babeuf. The latter was involved in the Conspiracy of the Equals of 1796 intending to establish a revolutionary regime based on communal ownership, egalitarianism and the redistribution of property.[14] However, the plot was detected and he and several others involved were arrested and executed. Despite this setback, the example of the French Revolutionary regime and Babeuf's doomed insurrection was an inspiration for radical French thinkers such as Compte Henri de Saint Simon, Louis Blanc, Charles Fourier and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who declared that "Property is theft!".[15] By the 1830s and 1840s the egalitarian concepts of communism and the related ideas of socialism had become widely popular in French revolutionary circles thanks to the writings of social critics and philosophers such as Pierre Leroux and Théodore Dézamy whose critiques of bourgeoisie liberalism led to a widespread intellectual rejection of laissez-faire capitalism on both economic, philosophical, and moral grounds.[16]

Importantly one of Babeuf's co-conspirators, Philippe Buonarroti, survived the crackdown on the Conspiracy of the Equals, and went on to write the influential book "Babuef's Conspiracy for Equality" first published in 1828.[16] Buonarroti's works and teachings went on to inspire early Babouvist communist groups such as the Christian Communist League of the Just in 1836 led by Wilhelm Weitling which would later be merged with the Communist Correspondence Committee in Brussels.[17] This merger of the two groups in 1847 formed the Communist League, headed by German socialist labour leader Karl Schapper who then that same year tasked two founding members, Karl Marx and Fredrick Engels to write a manifesto laying out the principles of the new political party.[18]

Karl Marx

Karl Marx, founder of Marxism

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

Communism is the riddle of history solved, and it knows itself to be this solution.

— Karl Marx, 1844[19]

In the 1840s, a German philosopher and sociologist named Karl Marx (1818–1883), who was living in England after fleeing the authorities in the German states, where he was considered a political threat, began publishing books in which he outlined his theories for a variety of communism now known as Marxism. Marx was financially aided and supported by another German émigré, Friedrich Engels (1820–1895), who like Marx had fled from the German authorities in 1849.[20] Marx and Engels took on many influences from earlier philosophers and politically they were influenced by Maximilien Robespierre and several other radical figures of the French Revolution, whilst economically they were influenced by David Ricardo and philosophically they were influenced by Hegel.[21] Engels regularly met Marx at Chetham's Library in Manchester, England from 1845 and the alcove where they met remains identical to this day.[22][23] It was here that Engels relayed his experiences of industrial Manchester, chronicled in the Condition of the Working Class in England, highlighting the struggles of the working class.

Marx stated that "the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles", something that he believed was happening between the bourgeoisie (the select few upper class and upper middle class) who then controlled society and the proletariat (the working class masses) who toiled to produce everything but who had no political control. He purported the idea that human society moved through a series of progressive stages from primitive communism through to slavery, feudalism and then capitalism – and that this in turn would be replaced by communism. Therefore, for Marx communism was seen as inevitable, as well as desirable.

Marx founded the Communist Correspondence Committee in 1846 through which the various communists, socialists and other leftists across Europe could keep in contact with one another in the face of political repression. He then published The Communist Manifesto in 1848, which would prove to be one of the most influential communist texts ever written. He subsequently began work on a multi-volume epic that would examine and criticise the capitalist economy and the effect that it had upon politics, society and philosophy—the first volume of the work, which was known as Capital: Critique of Political Economy, was published in 1869. However, Marx and Engels were not only interested in writing about communism, as they were also active in supporting revolutionary activity that would lead to the creation of communist governments across Europe. They helped to found the International Workingmen's Association, which would later become known as the First International, to unite various communists and socialists – and Marx was elected to the Association's General Council.[24]

Early development of Marxism

During the latter half of the 19th century, various left-wing organisations across Europe continued to campaign against the many autocratic right-wing regimes that were then in power. In France in 1871, socialists set up a government known as the Paris Commune after the fall of Napoleon III, but they were soon overthrown and many of their members executed by counter-revolutionaries.[25] Meanwhile, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels joined the German Social-Democratic Party, which had been created in 1875, but which was outlawed in 1879 by the German government, then led by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, who deemed it to be a political threat due to its revolutionary nature and increasing number of supporters.[26] In 1890, the party was re-legalised and by this time it had fully adopted Marxist principles. It subsequently achieved a fifth of the vote in the German elections and some of its leaders, such as August Bebel and Wilhelm Liebknecht, became well-known public figures.[27]

At the time, Marxism took off not only in Germany, but it also gained popularity in Hungary, the Habsburg Monarchy and the Netherlands, although it did not achieve such success in other European nations like the United Kingdom, where Marx and Engels had been based.[28] Nonetheless, the new political ideology had gained sufficient support that an organisation was founded known as the Second International to unite the various Marxist groups around the world.[29]

.mw-parser-output .quotebox{background-color:#F9F9F9;border:1px solid #aaa;box-sizing:border-box;padding:10px;font-size:88%}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft{margin:0.5em 1.4em 0.8em 0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright{margin:0.5em 0 0.8em 1.4em}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.centered{margin:0.5em auto 0.8em auto}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft p,.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright p{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-title{background-color:#F9F9F9;text-align:center;font-size:larger;font-weight:bold}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:before{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" “ ";vertical-align:-45%;line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:after{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" ” ";line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .left-aligned{text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .right-aligned{text-align:right}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .center-aligned{text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .quotebox cite{display:block;font-style:normal}@media screen and (max-width:360px){.mw-parser-output .quotebox{min-width:100%;margin:0 0 0.8em!important;float:none!important}}

—Karl Marx, 1848[30]

However, as Marxism took off it also began to come under criticism from other European intellectuals, including fellow socialists and leftists. For instance, the Russian collectivist anarchist Mikhail Bakunin criticised what he believed were the flaws in the Marxian theory that the state would eventually dissolve under a Marxist government, instead he believed that the state would gain in power and become authoritarian. Criticism also came from other sociologists, such as the German Max Weber, who whilst admiring Marx disagreed with many of his assumptions on the nature of society. Some Marxists tried to adapt to these criticisms and the changing nature of capitalism and Eduard Bernstein emphasised the idea of Marxists bringing legal challenges against the current administrations over the treatment of the working classes rather than simply emphasising violent revolution as more orthodox Marxists did. Other Marxists opposed Bernstein and other revisionists, with many including Karl Kautsky, Otto Bauer, Rudolf Hilferding, Rosa Luxemburg, Vladimir Lenin and Georgi Plekhanov sticking steadfast to the concept of violently overthrowing what they saw as the bourgeoisie-controlled government and instead establishing a "dictatorship of the proletariat".

International communism: periodization

The Comintern's historical existence is divided among periods, regarding changes in the general policy it followed.[31][32][33]

- The War Communism period (1919–1923) which saw the forming of the International, the Russian Civil War, a general revolutionary upheaval after the October Revolution resulting in the formation of the first communist parties across the world and the defeat of workers' revolutionary movements in Germany, Hungary, Finland and Poland.

- The New Economic Policy period (1923–1929) which marked the end of the civil war in Russia and new economic measures taken by the Bolshevik government, the toning down of the revolutionary wave in Europe and internal struggles within the Bolshevik Party and the Comintern after Lenin's death and before Stalin's absolute consolidation of power.

- The Third Period (1929–1934), an ultra-left turn which saw rapid industrialization and collectivization in the Soviet Union under Stalin's rule, the refusal by communists to cooperate with social democrats in other countries (labeling them "social fascists") and the ultimate rise of Adolf Hitler in Germany, which led to the abandonment of the hard-line policy of this period. These years also saw the complete subordination of all communist parties across the world to the directives of the Soviet Party, making the Comintern more or less an organ of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

- The Popular Front period (1934–1939) which marked the call by Comintern to all popular and democratic forces (not just communist) to unite in popular fronts against fascism. Products of this period were the popular front governments in France and Spain. However, this period was also marked by widespread purges of anyone suspected as an enemy of the Stalinist regime, both in the Soviet Union and abroad. These mass purges resulted in the breaking up of the popular front in Spain amidst the Spanish Civil War and the fall of Spain to Francisco Franco.

- The period of "advocating peace" (1939–1941), a result of the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact which resulted in the Soviet invasion of Poland. In this period, communists were advocating non-participation in World War II, labeling the war as "imperialist". A new term, "revolutionary defeatism", was coined by Comintern in this period, referring to anti-war propaganda by communists in the Western Europe against their national governments.

- The Eastern Front (World War II) period, sometimes called the Second Popular Front (1941–1943), was the last period of the Comintern, starting immediately after the German invasion of the Soviet Union, with Stalin's 3 July 1941 call to the entire free world to unite and fight Nazism by all means. This was a period of militant anti-fascism, the emergence of national liberation movements all across occupied Europe and ultimately the dissolution of the Comintern in 1943.

- The Early Cold War (1947–1960) in which the Soviet Union and the Red Army installed the communist regime's in most of Eastern Europe (except for Yugoslavia and Albania, which had independent communist regimes). A major effort to support communist party activity in Western democracies, especially Italy and France, fell short of gaining positions in the government.

- The Late Cold War (1960–1970s) in which China turned against the Soviet Union and organized alternative communist parties in many countries. Intense attention was given to revolutionary movements in the Third World, which were successful in some places such as Cuba and Vietnam. Communism was decisively defeated in other states, including Malaya and Indonesia. In 1972–1979, there was détente between the Soviet Union and the United States.

- The end of communism in Europe (1980–1992) in which Soviet client states were heavily on the defensive, as in Afghanistan and Nicaragua. The United States escalated the conflict with very heavy military spending. After a series of short-lived leaders, Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in the Kremlin and began a policy of glasnost and perestroika, designed to revive the stagnating Soviet economy. European satellites led by Poland grew increasingly independent and in 1989 they all expelled the communist leadership. East Germany merged into West Germany with Moscow's approval. At the end of 1991, the Soviet Union itself was dissolved into non-communist independent states. Many communist parties around the world either collapsed, or became independent non-communist entities. However, China, North Korea, Laos, Vietnam and Cuba maintained communist regimes. After 1980, China adopted a market oriented economy that welcomed large-scale trade and friendly relations with United States.

The early Communist states (1917–1944)

The Russian Revolution and the formation of the Soviet Union

At the start of the 20th century, the Russian Empire was an autocracy controlled by Tsar Nicholas II, with millions of the country's largely agrarian population living in abject poverty and the anti-communist historian Robert Service noted that "poverty and oppression constituted the best soil for Marxism to grow in".[34] The man responsible for largely introducing the ideology into the country was Georgi Plekhanov, although the movement itself was largely organised by a man known as Vladimir Lenin, who had for a time been exiled to a prison camp in Siberia by the Tsarist government for his beliefs.[35] A Marxist group known as the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party was formed in the country, although it soon divided into two main factions: the Bolsheviks led by Lenin and the Mensheviks led by Julius Martov. In 1905, there was a revolution against the Tsar's rule, in which workers' councils known as "soviets" were formed in many parts of the country and the Tsar was forced to implement democratic reform, introducing an elected government, the Duma.[36]

In 1917, with further social unrest against the Duma and its part in involving Russia in the First World War, the Bolsheviks took power in the October Revolution. They subsequently began remodelling the country based upon communist principles, nationalising various industries and confiscating land from wealthy aristocrats and redistributing it amongst the peasants. They subsequently pulled out of the war against Germany by signing the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which was unpopular amongst many in Russia for it gave away large areas of land to Germany. From the outset, the new government faced resistance from a myriad of forces with differing perspectives, including anarchists, social democrats, who took power in the Democratic Republic of Georgia, Socialist-Revolutionaries, who formed the Komuch in Samara, Russia, scattered tsarist resistance forces known as the White Guard, as well as Western powers. This led to the events of the Russian civil war, which the Bolsheviks won and subsequently consolidated their power over the entire country, centralising power from the Kremlin in the capital city of Moscow. In 1922, the Russian SFS Republic was officially redesignated to be the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, whilst in 1924 Lenin resigned as leader of the Soviet Union due to poor health and soon died, with Joseph Stalin subsequently taking over control.

Comintern, Mongolia and the communist uprisings in Europe

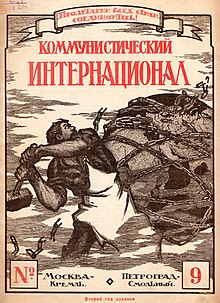

Comintern published a theoretical magazine in a variety of European languages from 1919 to 1943

In 1919, the Bolshevik government in Russia organised the creation of an international communist organisation that would act as the Third International after the collapse of the Second International in 1916 – this was known as the Communist International, although was commonly abbreviated as Comintern. Throughout its existence, Comintern would be dominated by the Kremlin despite its internationalist stance. Meanwhile, in 1921 the Soviet Union invaded its neighboring Mongolia to aid a popular uprising against the Chinese who then controlled the country, instituting a Marxist government, which declared the nation to be the Mongolian People's Republic in 1924.[37]

Comintern and other such Soviet-backed communist groups soon spread across much of the world, though particularly in Europe, where the influence of the recent Russian Revolution was still strong. In Germany, the Spartacist uprising took place in 1919, when armed communists supported rioting workers, but the government put the rebellion down violently with the use of a right-wing paramilitary group, the Freikorps, with many noted German communists, such as Rosa Luxemburg, being killed.[38] Within a few months, a group of communists seized power amongst public unrest in the German region of Bavaria, forming the Bavarian Soviet Republic, although once more this was put down violently by the Freikorps, who historians believe killed around 1200 communists and their sympathisers.[39]

That same year, political turmoil in Hungary following their defeat in the First World War led to a coalition government of the Social Democratic Party and the Communist Party taking control. The communists, led by Bela Kun, soon became dominant and instituted various communist reforms in the country, but the country was subsequently invaded by its neighbouring Romania within a matter of months who overthrew the government, with the communist leaders either escaping abroad or being executed.[40] In 1921, a communist revolt against the government occurred whilst supportive factory workers were on strike in Turin and Milan in northern Italy, but the government acted swiftly and put down the rebellion.[41] That same year, a further communist rebellion took place in Germany only to be crushed, but another occurred in 1923 which once again was also defeated by the government.[42] The communists of Bulgaria had also attempted an uprising in 1923, but like most of their counterparts across Europe they were defeated.[43]

Front organisations

Communist parties were tight knit organizations that exerted tight control over the members. To reach sympathisers unwilling to join the party, front organizations were created that advocated party-approved positions. The Comintern, under the leadership of Grigory Zinoviev in the Kremlin, established fronts in many countries in the 1920s and after. To coordinate their activities, the Comintern set up various international umbrella organizations (linking groups across national borders), such as the Young Communist International (youth), Profintern (trade unions),[44]Krestintern (peasants), International Red Aid (humanitarian aid), Sportintern (organized sports), etc. In Europe, front organizations were especially influential in Italy[45] and France, which in 1933 became the base for Communist front organizer Willi Münzenberg.[46] These organizations were dissolved the late 1930s or early 1940s.

The Pan-Pacific Trade Union Secretariat (PPTUS) was set up in 1927 by the Profintern (the Comintern's trade union arm) with the mission of promoting communist trade unions in China, Japan, Korea, the Philippines, Australia, New Zealand and other nations in the western Pacific.[47] Trapeznik (2009) says the PPTUS was a "Communist-front organization" and "engaged in overt and covert political agitation in addition to a number of clandestine activities".[48]

There were numerous Communist front organizations in Asia, many oriented to students and youth.[49] In Japan in the labor union movement of the 1920s, according to one historian, "The Hyogikai never called itself a communist front but in effect, this was what it was." He points out it was repressed by the government "along with other communist front groups".[50] In the 1950s, Scalapino argues, "The primary Communist-front organization was the Japan Peace Committee". It was founded in 1949.[51]

Stalinism in the Soviet Union

In 1924, Joseph Stalin, a key Bolshevik follower of Lenin, took power in the Soviet Union.[52] He was supported in his leadership by Nikolai Bukharin, but had various important opponents in the government, most notably Leon Trotsky, Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev. Stalin initiated his own process of building a communist society, creating a variant of communism known as Stalinism and as a part of this he abandoned some of the capitalist, free market policies that had been allowed to continue under Lenin, such as the New Economic Policy. He radically altered much of the Soviet Union's agricultural production, modernising it by introducing tractors and other machinery, by forced collectivisation of the farms, by forced collection of grains from the peasants in accordance with predecided targets. There was food available for industrial workers, but those peasants who refused to move starved especially in the Ukraine. The Communist Party targeted "Kulaks", who owned a little land.

Stalin took control of the Comintern, and introduced a policy in the international organisation of opposing all leftists who were not Marxists, labelling them to be "social-fascists", although many communists, such as Jules Humbert-Droz, disagreed with him on this policy, believing that the left should unite against the rise of right wing movements like fascism across Europe.[53] In the early 1930s, Stalin reversed course and promoted "popular front" movements whereby communist parties would collaborate with Socialists and other political forces. A high priority was mobilizing wide support for the Republican cause in the Spanish Civil War.[54]

The Great Terror

The "Great Terror" mainly operated from December 1936 to November 1938, although the features of arrest and summary trial followed by execution were well entrenched in the Soviet system since the days of Lenin, as Stalin systematically destroyed the older generation of pre-1918 leaders, usually on the grounds they were enemy spies or simply because they were "enemies of the people". In the Red Army, a majority of generals were executed and hundreds of thousands of other "enemies" were sent to the gulag,[55] where terrible conditions in Siberia led quickly to death.[56]

Pre-war dissident communisms

The International Right Opposition and Trotskyism are examples of dissidents who still claim communism today, but they are not the only ones. In Germany, the split in the SPD had initially led to a variety of Communist unions and parties forming, which included the councilist tendencies of the AAU-D, AAU-E and KAPD. Councilism had a limited impact outside of Germany, but a number of international organisations formed. In Spain, a fusion of Left and Right dissidents led to the formation of the POUM. Additionally, in Spain the CNT was associated with the development of the FAI political party, a non-Marxist party which stood for revolutionary communism.

Spreading communism (1945–1957)

As the Cold War took effect around 1947, the Kremlin set up new international coordination bodies including the World Federation of Democratic Youth, the International Union of Students, the World Federation of Trade Unions, the Women's International Democratic Federation and the World Peace Council. Kennedy says the, "Communist 'front' system included such international organizations as the WFTU, WFDY, IUS, WIDF and WPC, besides a host of lesser bodies bringing journalists, lawyers, scientists, doctors and others into the widespread net".[57]

The World Federation of Trade Unions (WFTU) was established in 1945 to unite trade union confederations across the world; it was based in Prague. While it had non-communist unions it was largely dominated by the Soviets. In 1949 the British, American and other non-Communist unions broke away to form the rival International Confederation of Free Trade Unions. The labor movement in Europe became so polarized between the communists unions and social democratic and Christian labor unions, whereas front operations could no longer hide the sponsorship and they became less important.[58]

Soviet Union

The devastation of the war resulted in a massive recovery program involving the rebuilding of industrial plants, housing and transportation, as well as the demobilization and migration of millions of soldiers and civilians. In the midst of this turmoil during the winter of 1946–1947, the Soviet Union experienced the worst natural famine in the 20th century.[59] There was no serious opposition to Stalin, as the secret police continued to send possible suspects to the gulag.

Relations with the United States and Britain went from friendly to hostile, as they denounced Stalin's political controls over eastern Europe and his blockade of Berlin. By 1947, the Cold War had begun. Stalin himself believed that capitalism was a hollow shell and would crumble under increased non-military pressure exerted through proxies in countries like Italy. He greatly underestimated the economic strength of the West and instead of triumph saw the West build up alliances that were designed to permanently stop or "contain" Soviet expansion. In early 1950, Stalin gave the go-ahead for North Korea's invasion of South Korea, expecting a short war. He was stunned when the Americans entered and defeated the North Koreans, putting them almost on the Soviet border. Stalin supported China's entry into the Korean war, which drove the Americans back to the prewar boundaries, but which escalated tensions. The United States decided to mobilize its economy for a long contest with the Soviets, built the hydrogen bomb and strengthened the NATO alliance that covered Western Europe.[60]

According to Gorlizki and Khlevniuk (2004), Stalin's consistent and overriding goal after 1945 was to consolidate the nation's superpower status and in the face of his growing physical decrepitude to maintain his own hold on total power. Stalin created a leadership system that reflected historic czarist styles of paternalism and repression, yet was also quite modern. At the top, personal loyalty to Stalin counted for everything. However, Stalin also created powerful committees, elevated younger specialists and began major institutional innovations. In the teeth of persecution, Stalin's deputies cultivated informal norms and mutual understandings which provided the foundations for collective rule after his death.[61]

Eastern Europe

The military success of the Red Army in Central and Eastern Europe led to a consolidation of power in communist hands. In some cases, such as Czechoslovakia, this led to an enthusiastic support for socialism inspired by the Communist Party and a Social Democratic Party willing to fuse. In other cases, such as Poland or Hungary, the fusion of the Communist Party with the Social Democratic party was forcible and accomplished through undemocratic means. In many cases, the communist parties of Central Europe were faced with a population initially quite willing to reign in market forces, institute limited nationalisation of industry and supporting the development of intensive social welfare states, whereas broadly the population largely supported socialism. However, the purges of non-communist parties which supported socialism, combined with forced collectivisation of agriculture and a Soviet-bloc wide recession in 1953 led to deep unrest. This unrest first surfaced in Berlin in 1953, where Brecht ironically suggested that the Party ought to elect a new People. However, Khrushchev's Secret Speech of 1956 opened up internal debate, even if members were unaware, in both the Polish and Hungarian Communist Parties. This led to the Polish Crisis of 1956 which was resolved through change in Polish leadership and a negotiation between the Soviet and Polish parties over the direction of the Polish economy.

Hungarian Revolution of 1956

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 was a major challenge to Moscow's control of Eastern Europe.[62] This revolution saw general strikes, the formation of independent workers councils, the restoration of the Social Democratic Party as a party for revolutionary communism of a non-Soviet variety and the formation of two underground independent communist parties. The mainstream Communist Party was controlled for a period of about a week by non-Soviet aligned leaders. Two non-communist parties which supported the maintenance of socialism also regained their independence. This flowering of dissenting communism was crushed by a combination of a military invasion supported by heavy artillery and airstrikes; mass arrests, at least a thousand juridical executions and an uncounted number of summary executions; the crushing of the Central Workers Council of Greater Budapest; mass refugee flight; and a worldwide propaganda campaign. The effect of the Hungarian Revolution on other communist parties varied significantly, resulting in large membership losses in Anglophone communist parties.[63]

Prague Spring 1968

The Czechoslovak Communist Party began an ambitious reform agenda under Alexander Dubček. The plan to limit central control and make the economy more independent of the party threatened bedrock beliefs. On 20 August 1968, Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev ordered a massive military invasion by Warsaw Pact forces that destroyed the threat of internal liberalization.[64] At the same time, the Soviets threatened retaliation against the British-French-Israeli invasion of Egypt. The upshot was a collapse of any tendency toward détente, and the resignations of more intellectuals from Parties in the West.[65]

West Germany

West Germany (and West Berlin) were centers of East-West conflict during the Cold War and numerous communist fronts were established. For example, the Society for German–Soviet Friendship (GfDSF) had 13,000 members in West Germany, but it was banned in 1953 by some Länder as a communist front.[66] The Democratic Cultural League of Germany started off as a series of genuinely pluralistic bodies, but in 1950–1951 came under the control of communists. By 1952, the U.S. Embassy counted 54 "infiltrated organizations", which started independently, as well as 155 "front organizations", which had been Communist inspired from their start.[67]

The Association of the Victims of the Nazi Regime was set up to rally West Germans under the antifascist banner, but had to be dissolved when Moscow discovered it had been infiltrated by "Zionist agents".[68]

China's Great Leap Forward

Chairman Mao Zedong proclaiming the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949

Mao Zedong and the Communist Party came to power in China in 1949, as the Nationalists fled to the island of Taiwan. In 1950–1953, China engaged in a large-scale but undeclared war with the United States, South Korea and United Nations forces in the Korean War. It ended in a military stalemate, but it gave Mao the opportunity to identify and purge elements in China that seemed supportive of capitalism. At first there was close cooperation with Stalin, who sent in technical experts to aid the industrialization process along the line of the Soviet model of the 1930s.[69] After Stalin's death in 1953, relations with Moscow soured—Mao thought Stalin's successors had betrayed the Communist ideal. Mao charged that Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev was the leader of a "revisionist clique" which had turned against Marxism and Leninism was now setting the stage for the restoration of capitalism.[70] The two nations were at sword's point by 1960. Both began forging alliances with communist supporters around the globe, thereby splitting the worldwide movement into two hostile camps.[71]

Rejecting the Soviet model of rapid urbanization, Mao Zedong and his top aide Deng Xiaoping launched the "Great Leap Forward" in 1957–1961 with the goal of industrializing China overnight, using the peasant villages as the base rather than large cities.[72] Private ownership of land ended and the peasants worked in large collective farms that were now ordered to start up heavy industry operations, such as steel mills. Plants were built in remote locations, despite the lack of technical experts, managers, transportation or needed facilities. Industrialization failed, but the main result was a sharp unexpected decline in agricultural output, which led to mass famine and millions of deaths. The years of the Great Leap Forward in fact saw economic regression, with 1958 through 1961 being the only years between 1953 and 1983 in which China's economy saw negative growth. Political economist Dwight Perkins argues, "Enormous amounts of investment produced only modest increases in production or none at all. […] In short, the Great Leap was a very expensive disaster".[73] Deng, put in charge of rescuing the economy, adopted pragmatic policies that the idealistic Mao disliked. Mao for a while was in the shadows, but he returned to center stage and purged Deng and his allies in the "cultural revolution" (1966–1969).[74]

Early post-war dissident communisms

Following the Second World War, Trotskyism was wracked by increasing internal divisions over analysis and strategy. This was combined with an industrial impotence that was widely recognised. Additionally, the success of Soviet-aligned parties in Europe and Asia led to the persecution of Trotskyite intellectuals, such as the infamous purge of Vietnamese Trotskyists. The war had also strained social democratic parties in the West. In some cases, such as Italy, significant bodies of membership of the Social Democratic Party were inspired by the possibility of achieving advanced socialism. In Italy this group, combined with dissenting communists, began to discuss theory centred on the experience of work in modern factories, leading to Autonomist Marxism. In the United States, this theoretical development was paralleled by the Johnston-Forrest tendency, whereas in France a similar impulse occurred.

The Cold War and revisionism (1958–1979)

Maoism and the Cultural Revolution in China

The Cultural Revolution was an upheaval that targeted intellectuals and party leaders from 1966 through 1976. Mao's goal was to purify communism by removing pro-capitalists and traditionalists by imposing Maoist orthodoxy within the Communist Party. The movement paralyzed China politically and weakened the country economically, culturally and intellectually for years. Millions of people were accused, humiliated, stripped of power and either imprisoned, killed or most often sent to work as farm laborers. Mao insisted that these "revisionists" be removed through violent class struggle. The two most prominent militants were Marshall Lin Biao of the army and Mao's wife Jiang Qing. China's youth responded to Mao's appeal by forming Red Guard groups around the country. The movement spread into the military, urban workers and the Communist Party leadership itself. It resulted in widespread factional struggles in all walks of life. In the top leadership, it led to a mass purge of senior officials who were accused of taking a "capitalist road", most notably Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping. During the same period, Mao's personality cult grew to immense proportions. After Mao's death in 1976, the survivors were rehabilitated and many returned to power.[75]

The Cuban Revolution

The Cuban Revolution was a successful armed revolt led by Fidel Castro's 26th of July Movement against the regime of Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista. It ousted Batista on 1 January 1959, replacing his regime with Castro's revolutionary government. Castro's government later reformed along communist lines, becoming the present Communist Party of Cuba in October 1965.[76] The United States response was highly negative, leading to a failed invasion attempt in 1961. The Soviets decided to protect its ally by stationing nuclear weapons in Cuba in 1962. In the Cuban Missile Crisis, the United States vehemently opposed the Soviet Union move. There was serious fear of nuclear war for a few days, but a compromise was reached by which Moscow publicly removed its weapons and the United States secretly removed its from bases in Turkey and promised never to invade.[77]

African Communism

Monument to Marxism built by the Derg in Addis Abba

During the Decolonization of Africa, the Soviet Union took a keen interest in that continent's independence movements and initially hoped that the cultivation of communist client states there would deny their economic and strategic resources to the West.[78] Soviet foreign policy with regards to Africa assumed that newly independent African governments would be receptive to Marxist ideology and that the Soviets would have the resources to make them attractive as development partners.[78] During the 1970s, the ruling parties of several sub-Saharan African states formally embraced communism, including Burkina Faso, the People's Republic of Benin, the People's Republic of Mozambique, the People's Republic of the Congo, the People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia and the People's Republic of Angola.[79] Most of these regimes ensured the selective adoption and flexible application of Marxist theory set against a broad ideological commitment to Marxism or Leninism.[79] The adoption of communism was often seen as a means to an end and used to justify the extreme centralization of power.[79]

Angola was perhaps the only African state which made a longstanding commitment to orthodox Marxism,[80] but this was severely hampered by its own war-burdened economy, rampant corruption and practical realities which allowed a few foreign companies to wield considerable influence despite the elimination of the domestic Angolan private sector and a substantial degree of central economic planning.[81][82] Both Angola and Ethiopia built new social and political communist institutions modeled closely after those in the Soviet Union and Cuba.[5] However, after the collapse of the Soviet Union their regimes either dissolved due to civil conflict or voluntarily repudiated communism in favour of social democracy.[5]

Eurocommunism

An important trend in several countries in Western Europe from the late 1960s into the 1980s was "Eurocommunism". It was strongest in Spain's PCE, Finland's party and especially in Italy's PCI, where it drew on the ideas of Antonio Gramsci. It was developed by members of the Communist Party who were disillusioned with both the Soviet Union and China and sought an independent program. They accepted liberal parliamentary democracy and free speech, as well as with some conditions accepted a capitalist market economy. They did not speak of the destruction of capitalism, but sought to win the support of the masses and by a gradual transformation of the bureaucracies. In 1978, Spain's PCE replaced the historic "Marxist–Leninist" catchphrase with the new slogan, "Marxist, democratic and revolutionary". The movement faded in the 1980s and collapsed with the fall of communism in Eastern Europe in 1989.[83]

The collapse of the Communist Powers (1980–1992)

Contemporary communism (1993–present)

With the fall of the communist governments in the Soviet Union and the eastern bloc, the power that the state-based Marxist ideologies held on the world was weakened, but there are still many communist movements of various types and sizes around the world. Three other communist nations, particularly those in eastern Asia, the People's Republic of China, Vietnam and Laos, all moved toward market economies, but without major privatization of the state sector during the 1980s and 1990s (see Socialism with Chinese characteristics and doi moi for more details).[citation needed]Spain, France, Portugal and Greece have very publicly strong communist movements that play an open and active leading role in the vast majority of their labor marches and strikes, as well as also anti-austerity protests, all of which are large, pronounced events with much visibility. Also, worldwide marches on International Workers Day sometimes give a clearer picture of the size and influence of current communist movements, particularly within Europe.

Cuba has recently emerged from the crisis sparked by the fall of the Soviet Union given the growth in its volume of trade with its new allies Venezuela and China (the former of whom has recently adopted a "socialism of the 21st century" according to Hugo Chavez). Various other countries throughout South and Latin America have also taken similar shifts to more clearly socialistic policies and rhetoric in a phenomenon academics are calling the "pink tide".

North Korea has had less success in coping with the collapse of the Soviet bloc than its counterparts, which led that government to "supersede" its original Marxism–Leninism with an ideology called Juche. However, Cuba does apparently have an ambassador to North Korea and China still protects North Korean territorial integrity even as it simultaneously refuses to supply the state with material goods or other significant assistance.

In Nepal, the Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist–Leninist) leader Man Mohan Adhikari briefly became Prime Minister and national leader from 1994 to 1995 and the Maoist guerrilla leader Prachanda was elected Prime Minister by the Constituent Assembly of Nepal in 2008. Prachanda has since been deposed as Prime Minister, leading the Maoists to abandon their legalistic approach and return to their typical street actions and militancy and to lead sporadic general strikes using their quite substantial influence on the Nepalese labor movement. These actions have oscillated between mild and intense, only the latter of which tends to make world news. They consider Prachanda's removal to be unjust.

The previous national government of India depended on the parliamentary support of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) and CPI(M) leads the state governments in West Bengal, Kerala and Tripura. The armed wing of the Communist Party of India (Maoist) is fighting a war against the government of India and is active in half the country, but the Indian government has recently declared[when?] the Maoists its chief objective to eliminate.

In Cyprus, the veteran communist Dimitris Christofias of AKEL won the 2008 presidential election.

In Moldova, the communist party won the 2001, 2005 and 2009 parliamentary elections. However, the April 2009 Moldovan elections results, in which the communists supposedly won a third time, were massively protested (including an attack on the Parliament and Presidency buildings by angry crowds) and another round was held on July 29 in which three opposition parties (the Liberals, Liberal-Democrats and Democrats) won and formed the Alliance for European Integration. However, failing to elect the president, new parliamentary elections were held in November 2010 which resulted in roughly the same representation in the Parliament. According to Ion Marandici, a Moldovan political scientist, the Moldovan communists differ from those in other countries because they managed to appeal to the ethnic minorities and the anti-Romanian Moldovans. After tracing the adaptation strategy of the Party of Communists from Moldova, he finds confirming evidence for five of the factors contributing to the electoral success, already mentioned in the theoretical literature on former communist parties: the economic situation, the weakness of the opponents, the electoral laws, the fragmentation of the political spectrum and the legacy of the old regime. However, Marandici identified seven additional explanatory factors at work in the Moldovan case: the foreign support for certain political parties, separatism, the appeal to the ethnic minorities, the alliance-building capacity, the reliance on the Soviet notion of the Moldovan identity, the state-building process and the control over a significant portion of the media. It is due to these seven additional factors that the successor party in Moldova managed to consolidate and expand its constituency. According to Marandici, in the post-Soviet area the Moldovan communists are the only ones who have been in power for so long and did not change the name of the party.[84]

In Ukraine and Russia, the communists came second in the 2002 and 2003 elections, respectively. The party remains strong in Russia, but in Ukraine following the 2014 Russian invasion of Ukraine and Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation the Ukrainian parliamentary election, 2014 resulted in the loss of its 32 members and no parliamentary representation by the Communist Party of Ukraine.[85]

In the Czech Republic, the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia came third in the 2002 elections, as did the Communist Party of Portugal in 2005.

In South Africa, the South African Communist Party (SACP) is a member of the Tripartite alliance alongside the African National Congress and the Congress of South African Trade Unions. Sri Lanka has communist ministers in their national governments.

In Zimbabwe, former President Robert Mugabe of the Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front, the country's longstanding leader, is a professed Marxist.[86][87]

Colombia is in the midst of a civil war which has been waged since 1966 between the Colombian government and aligned rightwing paramilitaries against two communist guerrilla groups: the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia–People's Army (FARC–EP) and the National Liberation Army (ELN).

The Philippines is still experiencing a low scale guerrilla insurgency by the New People's Army.

Sources

^ abcdefgh Lansford, Thomas (2007). Communism. New York: Cavendish Square Publishing. pp. 9–24, 36–44. ISBN 978-0761426288..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ abc Leopold, David (2015). Freeden, Michael; Stears, Marc; Sargent, Lyman Tower, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 20–38. ISBN 978-0198744337.

^ abc Schwarzmantle, John (2017). Breuilly, John, ed. The Oxford Handbook of the History of Nationalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 643–651. ISBN 978-0198768203.

^ abc MacFarlane, S. Neil (1990). Katz, Mark, ed. The USSR and Marxist Revolutions in the Third World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 6–11. ISBN 978-0812216202.

^ abc Dunn, Dennis (2016). A History of Orthodox, Islamic, and Western Christian Political Values. Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan. pp. 126–131. ISBN 978-3319325668.

^ Stephen Kotkin (3 November 2017). "Communism's Bloody Century". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 4 November 2017. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

^ "Vie d'Hupay"

^ Cassely, 2016: Aix insolite et secrète JonGlez p. 192-193 (références Bibliothèque nationale de France)

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 31 January 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2017.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ Service (2007:14-15)

^ Service (2007:15)

^ Service (2007:16)

^ David Priestland (2010) The Red Flag: Communism and the Making of the Modern World. Penguin: 5–7

^ David Priestland (2010) The Red Flag: Communism and the Making of the Modern World. Penguin: 18-19

^ Service (2007:16-17)

^ ab Paul E Corcoran; Christian Fuchs (25 August 1983). Before Marx: Socialism and Communism in France, 1830–48. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 3-5,22. ISBN 978-1-349-17146-0.

^ Franz Mehring, Karl Marx: The Story of His Life. Edward Fitzgerald, trans. London: George Allen and Unwin, 1936; pg. 139.

^ Christian Fuchs (23 October 2015). Reading Marx in the Information Age: A Media and Communication Studies Perspective on Capital. Routledge. p. 357. ISBN 978-1-317-36449-8.

^ Private Property and Communism by Karl Marx, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844

^ Service (2007:24-25)

^ Service (2007:13)

^ "101 Treasures of Chetham's". Chetham's Library. Archived from the original on 10 November 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2011.Philosophers Karl Marx and Frederich Engels met to research their Communist theory in Chetham's Library

^ "War and cotton lent Chetham's its name in Manchester". BBC News. 2 March 2010. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

^ Service (2007:27-28)

^ Service (2007:28)

^ Service (2007:29)

^ Service (2007:36)

^ Service (2007:39-41)

^ Service (2007:36-37)

^ Chapter IV. Position of the Communists in Relation to the Various Existing Opposition Parties by Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto

^ Richard Pipes, Communism: A History (2003)

^ David Priestland, The Red Flag: A History of Communism (2010)

^ Robert Service, Comrades: Communism: A World History (2011)

^ Service (2007:46)

^ Service (2007:48-49)

^ Service (2007:50-51)

^ Service (2007:115-116)

^ Service (2007:86)

^ Service (2007:90-92)

^ Service (2007:86-90)

^ Service (2007:92-94)

^ Service (2007:95-96)

^ Service (2007:117-118)

^ Ian Birchall, "Profintern: Die Rote Gewerkschaftsinternationale 1920–1937," Historical Materialism, 2009, Vol. 17 Issue 4, pp 164-176, review (in English) of a German language study by Reiner Tosstorff.

^ Joan Urban, Moscow and the Italian Communist Party: from Togliatti to Berlinguer (1986) p. 157

^ Julian Jackson, The Popular Front in France (1990) p. x

^ Harvey Klehr, John Earl Haynes, and Fridrikh Igorevich Firsov, The Secret World of American Communism (1996) p 42

^ Alexander Trapeznik, "'Agents of Moscow' at the Dawn of the Cold War: The Comintern and the Communist Party of New Zealand," Journal of Cold War Studies Volume 11, Number 1, Winter 2009 pp. 124-49 quote on p 144

^ For listings of front organizations in East Asia see Malcolm Kennedy, History of Communism in East Asia (Praeger Publishers, 1957) pp 118, 127-8, 130, 277, 334, 355, 361-7, 374, 415, 421, 424, 429, 439, 444, 457-8, 470, 482

^ Stephen S. Large, Organized Workers and Socialist Politics in Interwar Japan (2010) p. 85

^ Robert A. Scalapino, The Japanese Communist Movement 1920-1967 (1967) p 117

^ Archie Brown, The Rise & Fall of Communism (2010) pp62-77.

^ Service (2007:167)

^ Brown, The Rise and Fall of Communism, pp 88-90

^ Anne Applebaum, Gulag: A History. 2003. 736 pp. excerpt and text search

^ The exact number of victims is unknown by a factor of 10, from several million upwards to 20 million. Service says 1.5 million were arrested and 200,000 were eventually released. Service ch 31 esp p.356. The lowest estimates by Getty give more than 300,000 executions in each of the years 1937 and 1938. J. Arch Getty and Roberta T. Manning, eds., Stalinist Terror: New Perspectives (1993)

^ Malcolm Kennedy, History of Communism in East Asia (Praeger Publishers, 1957) p 126

^ Anthony Carew, "The Schism within the World Federation of Trade Unions: Government and Trade-Union Diplomacy," International Review of Social History, Dec 1984, Vol. 29 Issue 3, pp 297-335

^ Yoram Gorlizki and Oleg Khlevniuk, Stalin and the Soviet Ruling Circle, 1945-1953 (2004) pp 3ff

^ John Lewis Gaddis, A New History of the Cold War (2006)

^ Yoram Gorlizki, and Oleg Khlevniuk. Stalin and the Soviet Ruling Circle, 1945-1953 (2004) online edition

^ Erwin Schmidl, et al. The Hungarian Revolution 1956 (2006)

^ Brown, The Rise and Fall of Communism pp 278-92

^ Günter Bischof et al., eds. (2010). The Prague Spring and the Warsaw Pact Invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. Rowman & Littlefield.CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

^ Maude Bracke, Which Socialism, Whose Détente? West European Communism and the Czechoslovak Crisis of 1968 (2009)

^ Patrick Major, The Death of the KPD: Communism and Anti-Communism in West Germany, 1945-1956 (Oxford University Press, 1997) p. 215

^ Major, The Death of the KPD: Communism and Anti-Communism in West Germany, 1945-1956 pp 217–18

^ Vojtech Mastny, The Cold War and Soviet Insecurity: The Stalin Years (Oxford U.P., 1998) p. 162

^ Brown, Archie. The Rise and Fall of Communism. pp. 179–93. ISBN 0-0618-8548-7.

^ John Gittings (2006). The Changing Face of China:From Mao to Market. Oxford U.P. p. 40.

^ Lorenz M. Luthi (2010). The Sino-Soviet Split: Cold War in the Communist World. Princeton U.P.

^ Brown, Archie. The Rise and Fall of Communism. pp. 316–32. ISBN 0-0618-8548-7.

^ Dwight Heald Perkins (1984). China's economic policy and performance during the Cultural Revolution and its aftermath. Harvard Institute for International Development,. p. 12.

^ Ezra F. Vogel (2011). Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China. Harvard University Press. pp. 40–42.

^ Brown, The Rise & Fall of Communism, pp 324-32

^ Marifeli Perez-Stable, The Cuban Revolution: Origins, Course, and Legacy (3rd ed. 2011)

^ Brown, The Rise and fall of Communism, pp 293-312

^ ab Magyar, Karl; Danopoulos, Constantine (2002) [1994]. Prolonged Wars: A Post Nuclear Challenge. Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific. pp. 260–271. ISBN 978-0898758344.

^ abc Markakis, John; Waller, Michael (1986). Military Marxist Regimes in Africa. New York: Routledge Books. pp. 131–134. ISBN 978-0714632957.

^ Johnson, Elliott; Walker, David; Gray, Daniel (2014). Historical Dictionary of Marxism. Historical Dictionaries of Religions, Philosophies, and Movements (2nd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 294. ISBN 978-1-4422-3798-8.

^ Ferreira, Manuel (2002). Brauer, Jurgen; Dunne, J. Paul, eds. Arming the South: The Economics of Military Expenditure, Arms Production and Arms Trade in Developing Countries. Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan. pp. 251–255. ISBN 978-0-230-50125-6.

^ Akongdit, Addis Ababa Othow (2013). Impact of Political Stability on Economic Development: Case of South Sudan. Bloomington: AuthorHouse Ltd, Publishers. pp. 74–75. ISBN 978-1491876442.

^ David Priestland (2009). The Red Flag: A History of Communism. Grove Press. pp. 497–99.

^ Marandici, Ion, The Factors Leading to the Electoral Success, Consolidation and Decline of the Moldovan Communists' Party During the Transition Period (23 April 2010). Presented at the Midwestern Political Science Association Convention from April 2010. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1809029

^ People's Front 0.33% ahead of Poroshenko Bloc with all ballots counted in Ukraine elections - CEC Archived 12 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine., Interfax-Ukraine (8 November 2014)

^ Lunch with the Mugabes

^ From Liberator to Tyrant: Recollections of Mugabe

Further reading

Brown, Archie. The Rise & Fall of Communism. Vintage, London, 2010.

ISBN 978-1-84595-067-5

Davin, Delia (2013). Mao: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford UP.

- Pathak, Rakesh, and Yvonne Berliner. Communism in Crisis 1976-89 (2012), textbook

Pipes, Richard. Communism: A History (2003)- Pons, Silvio and Robert Service, eds. A Dictionary of 20th-Century Communism (Princeton University Press, 2010). 944 pp.

ISBN 978-0-691-13585-4 online review

- Priestland, David. The Red Flag: A History of Communism (2010)

Service, Robert. Comrades: Communism: A World History (Pan MacMillan, 2008) 571 pages;

ISBN 0-330-43968-5

- Sandle, Mark. Communism (2nd ed. 2011), short introduction

Service, Robert. Lenin: A Biography (2000) excerpt and text search

Taubman, William. Khrushchev: The Man and His Era (2004) excerpt and text search

- Tucker, Robert C. Stalin as Revolutionary, 1879-1929 (1973); Stalin in Power: The Revolution from Above, 1929-1941. (1990) online edition a standard biography; online at ACLS e-books

These

Primary sources

- Daniels, Robert V., ed. A Documentary History of Communism in Russia: From Lenin to Gorbachev (1993)

External links

BBC animation showing fall of Communism in Europe

The Red Flag: Communism and the Making of the Modern World – book review by Quentin Peel for The Financial Times

Comments

Post a Comment