HMCS Kamsack

HMCS Kamsack | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Kamsack |

| Namesake: | Kamsack, Saskatchewan |

| Ordered: | 1 February 1940 |

| Builder: | Port Arthur Shipbuilding Co. Port Arthur |

| Laid down: | 20 November 1940 |

| Launched: | 5 May 1941 |

| Commissioned: | 4 October 1941 |

| Decommissioned: | 22 July 1945 |

| Identification: | Pennant number: K171 |

| Honours and awards: | Atlantic 1942–44[1] |

| Fate: | sold to Venezuelan navy |

| Name: | Carabobo |

| Acquired: | purchased from Royal Canadian Navy |

| Commissioned: | 1945 |

| Out of service: | December 1945 |

| Fate: | wrecked December 1945 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Flower-class corvette[2] |

| Displacement: | 950 long tons (970 t; 1,060 short tons) |

| Length: | 205 ft (62.48 m) |

| Beam: | 33 ft (10.06 m) |

| Draught: | 11.5 ft (3.51 m) |

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 16 knots (29.6 km/h) |

| Range: | 3,450 nmi (6,390 km; 3,970 mi) at 12 kn (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Complement: | 6 officers, 79 men |

| Sensors and processing systems: |

|

| Armament: |

|

HMCS Kamsack was a Flower-class corvette that served with the Royal Canadian Navy during the Second World War. She served primarily in the Battle of the Atlantic as an ocean escort. She was named for Kamsack, Saskatchewan.

Contents

1 Background

2 Construction

3 Service history

3.1 War service

3.2 Postwar service

4 Notes

5 External links

Background

Flower-class corvettes like Kamsack serving with the Royal Canadian Navy during the Second World War were different from earlier and more traditional sail-driven corvettes.[3][4][5] The "corvette" designation was created by the French as a class of small warships; the Royal Navy borrowed the term for a period but discontinued its use in 1877.[6] During the hurried preparations for war in the late 1930s, Winston Churchill reactivated the corvette class, needing a name for smaller ships used in an escort capacity, in this case based on a whaling ship design.[7] The generic name "flower" was used to designate the class of these ships, which – in the Royal Navy – were named after flowering plants.[8]

Corvettes commissioned by the Royal Canadian Navy during the Second World War were named after communities for the most part, to better represent the people who took part in building them. This idea was put forth by Admiral Percy W. Nelles. Sponsors were commonly associated with the community for which the ship was named. Royal Navy corvettes were designed as open sea escorts, while Canadian corvettes were developed for coastal auxiliary roles which was exemplified by their minesweeping gear. Eventually the Canadian corvettes would be modified to allow them to perform better on the open seas.[9]

Construction

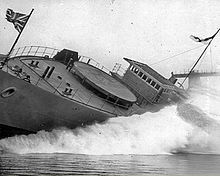

The launch of Kamsack – 5 May 1941.

Kamsack was ordered on 1 February 1940 as part of the 1939–1940 Flower-class building program. She was laid down 20 November 1940 by Port Arthur Shipbuilding Co. in Port Arthur, Ontario and launched 5 May 1941.[10]Kamsack was commissioned on 4 October 1941 in Quebec and arrived at Halifax on 13 October for workups.[11]

During her career, Kamsack had two major refits. The first refit took place at Liverpool, Nova Scotia beginning on 12 November 1942 and was completed at Halifax 18 January 1943. The second major refit took place in Baltimore, Maryland from December 1943 and took until mid-March 1944 to complete. During this second refit, Kamsack had her fo'c'sle extended.[11]

Service history

War service

Stand easy in the stoker's mess of Kamsack

After workups, Kamsack initially joined Sydney Force. However, in December 1941, she began her service with the Newfoundland Escort Force as part of escort group N13. In April 1942, Kamsack joined the Mid-Ocean Escort Force (MOEF) for two months as a part of escort group C-3. In June 1942, she transferred to the Western Local Escort Force (WLEF), with whom Kamsack would spend the rest of the war with. As a member of WLEF, in June 1943 she was assigned to escort group W-4 and in April 1944, group W-3.[11]

Postwar service

Kamsack was paid off on 22 July 1945 at Sorel, Quebec. She was quickly sold to the Venezuelan Navy who purchased her later that year. Renamed ARV Carabobo, she was wrecked during passage to Venezuela in December 1945.[2][11]

Notes

^ "Battle Honours". Britain's Navy. Retrieved 13 August 2013..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab Lenton, H.T.; Colledge, J.J (1968). British and Dominion Warships of World War II. Doubleday & Company. pp. 201, 212.

^ Ossian, Robert. "Complete List of Sailing Vessels". The Pirate King. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

^ Fitzsimons, Bernard, ed. (1978). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of 20th Century Weapons & Warfare. 11. London: Phoebus. pp. 1137–1142.

^ Jane's Fighting Ships of World War II. New Jersey: Random House. 1996. p. 68. ISBN 0-517-67963-9.

^ Blake, Nicholas; Lawrence, Richard (2005). The Illustrated Companion to Nelson's Navy. Stackpole Books. pp. 39–63. ISBN 0-8117-3275-4.

^ Chesneau, Roger; Gardiner, Robert (June 1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships (1922–1946). Naval Institute Press. p. 62. ISBN 0-87021-913-8.

^ Milner, Marc (1985). North Atlantic Run. Naval Institute Press. pp. 117–119, 142–145, 158, 175–176, 226, 235, 285–291. ISBN 0-87021-450-0.

^ Macpherson, Ken; Milner, Marc (1993). Corvettes of the Royal Canadian Navy 1939–1945. St. Catharines: Vanwell Publishing. ISBN 1-55125-052-7.

^ "HMCS Kamsack (K 171)". Uboat.net. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

^ abcd Macpherson, Ken; Burgess, John (1981). The ships of Canada's naval forces 1910–1981 : a complete pictorial history of Canadian warships. Toronto: Collins. pp. 77, 231. ISBN 0-00216-856-1.

External links

Hazegray. "Flower Class". Canadian Navy of Yesterday and Today. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

Ready, Aye, Ready. "HMCS Kamsack". Retrieved 13 August 2013.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

Comments

Post a Comment