Nothofagus

| Southern beeches Temporal range: 72–0 Ma PreЄ Є O S D C P T J K Pg N | |

|---|---|

| |

| The roble beech (Nothofagus obliqua) from South America | |

Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

Clade: | Angiosperms |

Clade: | Eudicots |

Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Fagales |

| Family: | Nothofagaceae Kuprian.[1] |

| Genus: | Nothofagus Blume |

| |

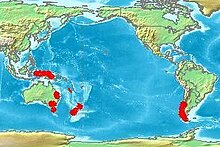

| The range of Nothofagus. | |

Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Shoots, leaves, and cupules of N. obliqua

Nothofagus, also known as the southern beeches, is a genus of 43 species[3] of trees and shrubs native to the Southern Hemisphere in southern South America (Chile, Argentina) and Australasia (east and southeast Australia, New Zealand, New Guinea and New Caledonia). The species are ecological dominants in many temperate forests in these regions.[4] Some species are reportedly naturalised in Germany and Great Britain.[2] The genus has a rich fossil record of leaves, cupules and pollen, with fossils extending into the late Cretaceous and occurring in Australia, New Zealand, Antarctica and South America.[5] In the past, they were included in the family Fagaceae, but genetic tests revealed them to be genetically distinct,[6] and they are now included in their own family, the Nothofagaceae.[7]

The leaves are toothed or entire, evergreen or deciduous. The fruit is a small, flattened or triangular nut, borne in cupules containing one to seven nuts.

Nothofagus species are used as food plants by the larvae of hepialid moths of the genus Aenetus, including A. eximia and A. virescens.

Many individual trees are extremely old, and at one time, some populations were thought to be unable to reproduce in present-day conditions where they were growing, except by suckering (clonal reproduction), being remnant forest from a cooler time. Sexual reproduction has since been shown to be possible.[8] Although the genus now mostly occurs in cool, isolated, high-altitude environments at temperate and tropical latitudes the fossil record shows that it survived in climates that appear to be much warmer than those that Nothofagus now occupies.[9]

Taxonomy

The genus is classified in these subgenera:[10]

- Subgenus Brassospora - type N. brassi (or genus Trisyngyne[11])

Nothofagus aequilateralis (New Caledonia)

Nothofagus balansae (New Caledonia)

Nothofagus baumanniae (New Caledonia)

Nothofagus brassii (New Guinea)

Nothofagus carrii (New Guinea)

Nothofagus codonandra (New Caledonia)

Nothofagus crenata (New Guinea)

Nothofagus discoidea (New Caledonia)

Nothofagus flaviramea (New Guinea)

Nothofagus grandis (New Guinea)

Nothofagus nuda (New Guinea)

Nothofagus perryi (New Guinea)

Nothofagus pseudoresinosa (New Guinea)

Nothofagus pullei (New Guinea)

Nothofagus resinosa (New Guinea)

Nothofagus rubra (New Guinea)

Nothofagus starkenborghii (New Guinea)

Nothofagus stylosa (New Guinea)

Nothofagus womersleyi (New Guinea)

Nothofagus mucronata (extinct) (Tasmania, Early Oligocene)[5]

Nothofagus serrata (extinct) (Tasmania, Early Oligocene)[5]

Nothofagus balfourensis (extinct) (Tasmania, Late Oligocene-Early Miocene)[5]

Nothofagus cooksoniae (extinct) (Tasmania, Early Oligocene)[5]

Nothofagus peduncularis (extinct) (Tasmania, Early Oligocene)[5]

Nothofagus robusta (extinct) (Tasmania, Early Oligocene)[5]

Nothofagus smithtonensis (extinct) (Tasmania, Early Oligocene)[5]

Nothofagus palustris (extinct) (New Zealand, Late Oligocene-Early Miocene)[12]

- Subgenus Fuscospora - type N. fusca (or genus Fuscospora[11])

Nothofagus alessandri (Central Chile)

Nothofagus fusca (New Zealand)

Nothofagus gunnii (Australia: Tasmania)

Nothofagus solandri (New Zealand)

Nothofagus truncata (New Zealand)

Nothofagus cethanica (extinct) (Tasmania, Early Oligocene)[5]

Beech trees in New Zealand

- Subgenus Lophozonia - type N. menziesii (or genus Lophozonia[11])

Nothofagus alpina (=N. procera) (Central Chile/Argentina)

Nothofagus cunninghamii (Australia: Victoria, Tasmania)

Nothofagus glauca (Central Chile)

Nothofagus leonii (Central Chile), (likely a hybrid between N. glauca and N. oblicua)[13]

Nothofagus macrocarpa (Central Chile, prov. Argentina)

Nothofagus menziesii (New Zealand)

Nothofagus moorei (Australia: New South Wales, Queensland)

Nothofagus obliqua (Chile/Argentina)

Nothofagus smithtonensis (extinct) (Tasmania, Early Oligocene)[5]

Nothofagus muelleri (extinct) (New South Wales, Late Eocene)[5]

Nothofagus novae-zealandiae (extinct) (New Zealand, Mid-Late Miocene)[5]

Nothofagus pachyphylla (extinct) (Tasmania, Early Pleistocene)[14]

Nothofagus tasmanica (extinct) (Tasmania, Eocene - Early Oligocene)[5]

- Subgenus Nothofagus - type N. antarctica

Nothofagus antarctica (Southern Argentina and Chile)

Nothofagus betuloides (Southern Argentina and Chile)

Nothofagus dombeyi (Central Chile and Andean Patagonia-Argentina)

Nothofagus nitida (Southern Chile and probably Argentina)

Nothofagus pumilio (Argentina/Chile)

Nothofagus lobata (extinct) (Tasmania, Early Oligocene)[5]

Nothofagus bulbosa (extinct) (Tasmania, Early Oligocene)[5]

- Subgenus uncertain

Nothofagus beardmorensis (extinct) (Antarctica, either ~3 million or ~15 million years old), see Antarctica#Neogene Period (23–0.05 mya) and Meyer Desert Formation biota[15][16]

It was recently proposed that the generic classification of the Nothofagaceae should be revised, with the four subgenera elevated to full genera.[11] This proposed change is not taxonomically essential [2][17] and has not been accepted outside New Zealand.

The Nothofagus plant genus illustrates the distribution on fragments of the old supercontinent Gondwana Australia, New Guinea, New Zealand, New Caledonia, Argentina and Chile. Fossils show that the genus originated on the supercontinent.

Distribution

The pattern of distribution around the southern Pacific Rim suggests the dissemination of the genus dates to the time when Antarctica, Australia, and South America were connected in a common land-mass or supercontinent referred to as Gondwana.[18] However, genetic evidence using molecular dating methods has been used to argue that the species in New Zealand and New Caledonia evolved from species that arrived in these landmasses by dispersal across oceans.[19] There is uncertainty in molecular dates and controversy rages as to whether the distribution of Nothofagus derives from the break-up of Gondwana (i.e. vicariance), or if there has been long distance dispersal across oceans. In South America the northern limit of the genus can be construed as La Campana National Park and the Vizcachas Mountains in the central part of Chile.[20]

Beech mast

Every four to six years or so, Nothofagus produces a heavier crop of seeds and is known as the beech mast. In New Zealand, the beech mast causes an increase in the population of introduced mammals such as mice, rats, and stoats. When the rodent population collapses, the stoats begin to prey on native bird species, many of which are threatened with extinction.[21] This phenomenon is covered in more detail in the article on stoats in New Zealand.

See also

Cyttaria, genus of ascomycete fungi found on or associated with Nothofagus

Misodendrum, specialist parasites of Nothofagus

References

^ Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (2009). "An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG III". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 161 (2): 105–121. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2009.00996.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-05-25. Retrieved 2013-06-26..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ abc Kew World Checklist of Selected Plant Families

^ Christenhusz, M. J. M.; Byng, J. W. (2016). "The number of known plants species in the world and its annual increase". Phytotaxa. 261 (3): 201–217. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.261.3.1.

^ Veblen, Thomas; Hill, Robert; Read, Jennifer (1996). Ecology and Biogeography of Nothofagus Forests. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06423-0.

^ abcdefghijklmno Hill, Robert (2001). "Biogeography, evolution and palaeoecology of Nothofagus (Nothofagaceae): The contribution of the fossil record". Australian Journal of Botany. 49 (3): 321. doi:10.1071/BT00026.

^ Manos PS, Steele KP (1997) Phylogenetic analyses of 'higher' Hamamelididae based on plastid sequence data. American Journal of Botany 84, 1407-1419. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2446139

^ Manos, Paul (1997). "Phylogenetic analyses of 'higher' Hamamelididae based on plastid sequence data". American Journal of Botany. 84 (10): 1407–1419. doi:10.2307/2446139. JSTOR 2446139.

^ http://cgi.cse.unsw.edu.au/~lambert/cgi-bin/clim/2005/07/

^ Carpenter, RJ; Jordan, GJ; Macphail, MK; Hill, RS (2012). "Near-tropical early eocene terrestrial temperatures at the Australo-Antarctic margin, western Tasmania". Geology. 40 (3): 267–270. Bibcode:2012Geo....40..267C. doi:10.1130/G32584.1.

^ Nothofagus website (in French)

^ abcd Heenan, P.B.; Smissen, R.D. (2013). "Revised circumscription of Nothofagus and recognition of the segregate genera Fuscospora, Lophozonia, and Trisyngyne (Nothofagaceae)". Phytotaxa. 146 (1): 1–31. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.146.1.1.

^ Carpenter, RJ; Bannister, JM; Lee, DE; Jordan, GJ (2014). "Nothofagus subgenus Brassospora (Nothofagaceae) leaf fossils from New Zealand: A link to Australia and New Guinea?". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 174 (4): 503–515. doi:10.1111/boj.12143.

^ San Martín, José; Donoso, Claudio (1995). "Estructura florística e impacto antrópico en el bosque Maulino de Chile" [Floristic structure and human impact on the Maulino forest of Chile]. In Armesto, Juan J.; Villagrán, Carolina; Arroyo, Mary Kalin. Ecología de los bosques nativos de Chile (in Spanish). Santiago de Chile: Editorial Universitaria. pp. 153–167. ISBN 978-9561112841.

^ Jordan, GJ (1999). "A new Early Pleistocene species of Nothofagus and the climatic implications of co-occurring Nothofagus fossils". Australian Systematic Botany. 12 (6): 757–765. doi:10.1071/sb98025.

^ Hill, R.S.; Harwood, D.M.; Webb, P.-N. (1996). "Nothofagus beardmorensis (Nothofagaceae), a new species based on leaves from the Pliocene Sirius Group, Transantarctic Mountains, Antarctica". Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 94 (1–2): 11–24. doi:10.1016/S0034-6667(96)00003-6.

^ Nothofagus beardmorensis Nothofagaceae, a new species based on leaves from the Pliocene Sirius Group, Transantarctic Mountains, Antarctica

^ Hill, RS; Jordan, GJ; Macphail, MK (2015). "Why we should retain Nothofagus sensu lato". Australian Systematic Botany. 28 (3): 190–193. doi:10.1071/sb15026.

^

Native Forest Network (2003) Gondwana Forest Sanctuary

^ Knapp, M; Stockler, K; Havell, D; Delsuc, F; Sebastiani, F; Lockhart, PJ (2005). "Relaxed molecular clock provides evidence for long-distance dispersal of Nothofagus (Southern Beech)". PLoS Biology. 3 (1): 38–43. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030014. PMC 539330. PMID 15660155.

^ C. Michael Hogan (2008) Chilean Wine Palm: Jubaea chilensis, GlobalTwitcher.com, ed. Nicklas Stromberg Archived 2012-10-17 at the Wayback Machine

^ "Beech forest: Native plants". Department of Conservation. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

Wikispecies has information related to Nothofagus |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nothofagus. |

Comments

Post a Comment