Mestranol

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Enovid, Norinyl, Ortho-Novum, others |

| Synonyms | Ethinylestradiol 3-methyl ether; EEME; EE3ME; CB-8027; L-33355; RS-1044; 17α-Ethynylestradiol 3-methyl ether; 17α-Ethynyl-3-methoxyestra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17β-ol; 3-Methoxy-19-norpregna-1,3,5(10)-trien-20-yn-17α-ol |

AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| MedlinePlus | a601050 |

| Routes of administration | By mouth[1] |

| Drug class | Estrogen; Estrogen ether |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number |

|

PubChem CID |

|

| IUPHAR/BPS |

|

| DrugBank |

|

| ChemSpider |

|

| UNII |

|

| KEGG |

|

| ChEBI |

|

| ChEMBL |

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.707 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H26O2 |

| Molar mass | 310.437 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) |

|

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

.mw-parser-output .nobold{font-weight:normal} (verify) | |

Mestranol, sold under the brand names Enovid, Norinyl, and Ortho-Novum among others, is an estrogen medication which has been used in birth control pills, menopausal hormone therapy, and the treatment of menstrual disorders.[1][2][3][4] It is formulated in combination with a progestin and is not available alone.[4] It is taken by mouth.[1]

Side effects of mestranol include nausea, breast tension, edema, and breakthrough bleeding among others.[5] It is an estrogen, or an agonist of the estrogen receptors, the biological target of estrogens like estradiol.[6] Mestranol is a prodrug of ethinylestradiol in the body.[6]

Mestranol was discovered in 1956 and was introduced for medical use in 1957.[7][8] It was the estrogen component in the first birth control pill.[7][8] In 1969, mestranol was replaced by ethinylestradiol in most birth control pills, although mestranol continues to be used in a few birth control pills even today.[9][4] Mestranol remains available only in a few countries, including the United States, United Kingdom, Japan, and Chile.[4]

Contents

1 Medical uses

2 Side effects

3 Pharmacology

4 Chemistry

5 History

6 Society and culture

6.1 Generic names

6.2 Brand names

6.3 Availability

7 References

Medical uses

Mestranol was employed as the estrogen component in many of the first oral contraceptives, such as mestranol/noretynodrel (brand name Enovid) and mestranol/norethisterone (brand names Ortho-Novum, Norinyl), and is still in use today.[2][3][4] In addition to its use as an oral contraceptive, mestranol has been used as a component of menopausal hormone therapy for the treatment of menopausal symptoms.[1]

Side effects

Pharmacology

Ethinylestradiol (EE), the active form of mestranol.

Mestranol is a biologically inactive prodrug of ethinylestradiol to which it is demethylated in the liver with a conversion efficiency of 70% (50 µg of mestranol is pharmacokinetically bioequivalent to 35 µg of ethinylestradiol, or ethinylestradiol being about 1.7 times as orally potent by weight as mestranol).[10][11][6] It has been found to possess about 2.3% of the relative binding affinity of estradiol (100%) for the estrogen receptor, compared to 190% for ethinylestradiol.[12]

| Estrogen | Type | EPD (mg/14 days) | EPD (mg/day) | MSD (mg/14 days) | MSD (mg/day) | TSD (mg/day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Estradiol (micronized) | Bioidentical | 60 | 4.3 | 14–28 | 1.0–2.0 | ND |

| Estradiol valerate | Bioidentical | 60 | 4.3 | 14–28 | 1.0–2.0 | ND |

| Estriol | Bioidentical | 140–150a | 10.0–10.7a | 28–84 | 2.0–6.0 | ND |

| Estriol succinate | Bioidentical | 140–150a | 10.0–10.7a | 28–84 | 2.0–6.0 | ND |

| Conjugated estrogens | Natural | 60 | 4.3 | 8.4–17.5 | 0.625–1.25 | 7.5 |

| Ethinylestradiol | Synthetic | 1.0–1.5 | 0.071–0.11 | 0.28 | 0.02 | 0.1 |

| Mestranol | Synthetic | 1.5–2.0 | 0.11–0.13 | 0.35 | 0.025 | ND |

| Quinestrol | Synthetic | 2.0–4.0 | 0.14–0.29 | ND | ND | ND |

| Diethylstilbestrol | Synthetic | 20–30 | 1.4–2.1 | ND | ND | 3 |

| Diethylstilbestrol dipropionate | Synthetic | 15–20 | 1.1–1.4 | ND | ND | ND |

| Dienestrol diacetate | Synthetic | 40–60 | 2.9–4.3 | ND | ND | ND |

Addendum: The ovulation-inhibiting dose (OID) of ethinylestradiol is 0.1 mg/day.[13]Footnotes: a = Taken in divided doses three times per day. Abbreviations: EPD = Endometrial proliferation dose. MSD = Menopausal substitution dose. TSD = Testosterone suppression dose (minimum dosage required to consistently suppress testosterone levels into the castrate range in men). Sources: [14][15][16][17][18] | ||||||

Chemistry

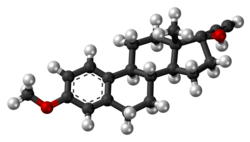

Mestranol, also known as ethinylestradiol 3-methyl ether (EEME) or as 17α-ethynyl-3-methoxyestra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17β-ol, is a synthetic estrane steroid and a derivative of estradiol.[19][20][21] It is specifically a derivative of ethinylestradiol (17α-ethynylestradiol) with a methyl ether at the C3 position.[19][20]

History

In April 1956, noretynodrel was investigated, in Puerto Rico, in the first large-scale clinical trial of a progestogen as an oral contraceptive.[7][8] The trial was conducted in Puerto Rico due to the high birth rate in the country and concerns of moral censure in the United States.[22] It was discovered early into the study that the initial chemical syntheses of noretynodrel had been contaminated with small amounts (1–2%) of the 3-methyl ether of ethinylestradiol (noretynodrel having been synthesized from ethinylestradiol).[7][8] When this impurity was removed, higher rates of breakthrough bleeding occurred.[7][8] As a result, mestranol, that same year (1956),[23] was developed and serendipitously identified as a very potent synthetic estrogen (and eventually as a prodrug of ethinylestradiol), given its name, and added back to the formulation.[7][8] This resulted in Enovid by G. D. Searle & Company, the first oral contraceptive and a combination of 9.85 mg noretynodrel and 150 μg mestranol per pill.[7][8]

Around 1969, mestranol was replaced by ethinylestradiol in most combined oral contraceptives due to widespread panic about the recently uncovered increased risk of venous thromboembolism with estrogen-containing oral contraceptives.[9] The rationale was that ethinylestradiol was approximately twice as potent by weight as mestranol and hence that the dose could be halved, which it was thought might result in a lower incidence of venous thromboembolism.[9] Whether this actually did result in a lower incidence of venous thromboembolism has never been assessed.[9]

Society and culture

Generic names

Mestranol is the generic name of the drug and its INN, USAN, USP, BAN, DCF, and JAN, while mestranolo is its DCIT.[19][20][1][4]

Brand names

Mestranol has been marketed under a variety of brand names, mostly or exclusively in combination with progestins, including Devocin, Enavid, Enovid, Femigen, Mestranol, Norbiogest, Ortho-Novin, Ortho-Novum, Ovastol, and Tranel among others.[2][19][24][20] Today, it continues to be sold in combination with progestins under brand names including Lutedion, Necon, Norinyl, Ortho-Novum, and Sophia.[4]

Availability

Mestranol remains available only in the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, and Chile.[4] It is only marketed in combination with progestins, such as norethisterone.[4]

References

^ abcde I.K. Morton; Judith M. Hall (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 177–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ abc Lara Marks (2010). Sexual Chemistry: A History of the Contraceptive Pill. Yale University Press. pp. 75–. ISBN 978-0-300-16791-7.

^ ab Robert W. Blum (22 October 2013). Adolescent Health Care: Clinical Issues. Elsevier Science. pp. 216–. ISBN 978-1-4832-7738-7.

^ abcdefghi https://www.drugs.com/international/mestranol.html

^ Wittlinger, H. (1980). "Clinical Effects of Estrogens": 67–71. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-67568-3_10.

^ abc Donna Shoupe (7 November 2007). The Handbook of Contraception: A Guide for Practical Management. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 23–. ISBN 978-1-59745-150-5.EE is about 1.7 times as potent as the same weight of mestranol.

^ abcdefg Walter Sneader (23 June 2005). Drug Discovery: A History. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 202–. ISBN 978-0-471-89979-2.

^ abcdefg Gretchen M. Lentz; Rogerio A. Lobo; David M. Gershenson; Vern L. Katz (2012). Comprehensive Gynecology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 224–. ISBN 0-323-06986-X.

^ abcd Jeffrey K. Aronson (21 February 2009). Meyler's Side Effects of Endocrine and Metabolic Drugs. Elsevier. pp. 224–. ISBN 978-0-08-093292-7.

^ Faigle, Johann W.; Schenkel, Lotte (1998). "Pharmacokinetics of estrogens and progestogens". In in Fraser; Ian S. Estrogens and Progestogens in Clinical Practice. London: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 273–294. ISBN 0-443-04706-5.

^ Tommaso Falcone; William W. Hurd (2007). Clinical Reproductive Medicine and Surgery. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 388–. ISBN 0-323-03309-1.

^ Blair RM, Fang H, Branham WS, Hass BS, Dial SL, Moland CL, Tong W, Shi L, Perkins R, Sheehan DM (March 2000). "The estrogen receptor relative binding affinities of 188 natural and xenochemicals: structural diversity of ligands". Toxicol. Sci. 54 (1): 138–53. PMID 10746941.

^ N. Rietbrock; A.H. Staib; D. Loew (11 March 2013). Klinische Pharmakologie: Arzneitherapie. Springer-Verlag. pp. 426–. ISBN 978-3-642-57636-2.

^ Lauritzen C (September 1990). "Clinical use of oestrogens and progestogens". Maturitas. 12 (3): 199–214. doi:10.1016/0378-5122(90)90004-P. PMID 2215269.

^ Alfred S. Wolf; H.P.G. Schneider (12 March 2013). Östrogene in Diagnostik und Therapie. Springer-Verlag. pp. 78–. ISBN 978-3-642-75101-1.

^ Gunther Göretzlehner; Christian Lauritzen; Thomas Römer; Winfried Rossmanith (1 January 2012). Praktische Hormontherapie in der Gynäkologie. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 44–. ISBN 978-3-11-024568-4.

^ Karl Knörr; Fritz K. Beller; Christian Lauritzen (17 April 2013). Lehrbuch der Gynäkologie. Springer-Verlag. pp. 212–213. ISBN 978-3-662-00942-0.

^ Scott WW, Menon M, Walsh PC (April 1980). "Hormonal Therapy of Prostatic Cancer". Cancer. 45 Suppl 7: 1929–1936. doi:10.1002/cncr.1980.45.s7.1929. PMID 29603164.

^ abcd J. Elks (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 775–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

^ abcd Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 656–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

^ A. Labhart (6 December 2012). Clinical Endocrinology: Theory and Practice. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 575–. ISBN 978-3-642-96158-8.

^ Marcus Filshie; John Guillebaud (22 October 2013). Contraception: Science and Practice. Elsevier Science. pp. 12–. ISBN 978-1-4831-6366-6.

^ Billingsley FS (1969). "Lactation suppression utilizing norethynodrel with mestranol". J Fla Med Assoc. 56 (2): 95–7. PMID 4884828.

^ William Andrew Publishing (22 October 2013). Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia, 3rd Edition. Elsevier. pp. 2109–. ISBN 978-0-8155-1856-3.

Comments

Post a Comment