Cuban Revolution

| Cuban Revolution | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Cold War | |||||||

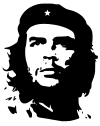

Revolutionary leaders Che Guevara (left) and Fidel Castro (right) in 1961 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

* Independent guerrilla groups * Urban militants |

Supported by: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

* Reynol Garcia | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

5,000+ combat-related deaths; unknown thousands of dissidents arrested and murdered by Batista's government; unknown number of people executed by the Rebel Army[1][2][3][4] | |||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Cuba |

|

Governorate of Cuba (1511–1519) |

Viceroyalty of New Spain (1535–1821) |

Captaincy General of Cuba (1607–1898) |

|

US Military Government (1898–1902) |

Republic of Cuba (1902–1959) |

|

Republic of Cuba (1959–) |

|

Timeline |

Topical |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism–Leninism |

|---|

|

Concepts

|

Variants

|

People

|

Literature

|

History

|

Related topics

|

|

The Cuban Revolution (Spanish: Revolución cubana) was an armed revolt conducted by Fidel Castro's revolutionary 26th of July Movement and its allies against the authoritarian government of Cuban President Fulgencio Batista. The revolution began in July 1953,[5] and continued sporadically until the rebels finally ousted Batista on 31 December 1958, replacing his government with a revolutionary socialist state. 26 July 1959 is celebrated in Cuba as the Day of the Revolution. The 26th of July Movement later reformed along communist lines, becoming the Communist Party in October 1965.[6]

The Cuban Revolution had powerful domestic and international repercussions. In particular, it transformed Cuba's relationship with the United States, although efforts to improve diplomatic relations have gained momentum in recent years.[7][8][9][10] In the immediate aftermath of the revolution, Castro's government began a program of nationalization and political consolidation that transformed Cuba's economy and civil society.[11][12] The revolution also heralded an era of Cuban intervention in foreign military conflicts, including the Angolan Civil War and the Nicaraguan Revolution.[13]

Contents

1 History

2 Early stages

3 Guerrilla warfare

4 Final offensive and rebel victory

5 Women's roles in the revolution

6 Aftermath

6.1 Reforms and nationalization

6.2 International reactions and foreign policy

6.3 Exiles and counterrevolutionary rebels

7 In popular culture

8 See also

9 References

10 Bibliography

11 Further reading

12 External links

History

In the decades following United States' invasion of Cuba in 1898, and formal independence from the U.S. on May 20, 1902, Cuba experienced a period of significant instability, enduring a number of revolts, coups and a period of U.S. military occupation. Fulgencio Batista, a former soldier who had served as the elected president of Cuba from 1940 to 1944, became president for the second time in 1952, after seizing power in a military coup and canceling the 1952 elections.[14] Although Batista had been relatively progressive during his first term,[15] in the 1950s he proved far more dictatorial and indifferent to popular concerns.[16] While Cuba remained plagued by high unemployment and limited water infrastructure,[17] Batista antagonized the population by forming lucrative links to organized crime and allowing American companies to dominate the Cuban economy, especially sugar-cane plantations and other local resources.[17][18][19] Although the US armed and politically supported the Batista dictatorship, later US presidents recognized its corruption and the justifiability of removing it.[20]

During his first term as President, Batista had not been supported by the Communist Party of Cuba,[15] but during his second term he became strongly anti-communist.[17][21] Batista developed a rather weak security bridge as an attempt to silence political opponents. In the months following the March 1952 coup, Fidel Castro, then a young lawyer and activist, petitioned for the overthrow of Batista, whom he accused of corruption and tyranny. However, Castro's constitutional arguments were rejected by the Cuban courts.[22] After deciding that the Cuban regime could not be replaced through legal means, Castro resolved to launch an armed revolution. To this end, he and his brother Raúl founded a paramilitary organization known as "The Movement", stockpiling weapons and recruiting around 1,200 followers from Havana's disgruntled working class by the end of 1952. Batista was known as a corrupt leader as he constantly pampered himself with elegant foods and exotic women.[23]

Early stages

Striking their first blow against the Batista government, Fidel and Raúl Castro gathered 69 Movement fighters and planned a multi-pronged attack on several military installations.[24] On 26 July 1953, the rebels attacked the Moncada Barracks in Santiago and the barracks in Bayamo, only to be decisively defeated by government soldiers.[5] It was hoped that the staged attack would spark a nationwide revolt against Batista's government. He had around 150 factory and farm workers. After an hour of fighting the rebel leader fled to the mountains.[25] The exact number of rebels killed in the battle is debatable; however, in his autobiography, Fidel Castro claimed that nine were killed in the fighting, and an additional 56 were executed after being captured by the Batista government.[26] Due to the government's large number of men, Hunt revised the number to be around 60 members taking the opportunity to flee to the mountains along with Castro.[27] Among the dead was Abel Santamaría, Castro's second-in-command, who was imprisoned, tortured, and executed on the same day as the attack.[28]

Numerous key Movement revolutionaries, including the Castro brothers, were captured shortly afterwards. In a highly political trial, Fidel spoke for nearly four hours in his defense, ending with the words "Condemn me, it does not matter. History will absolve me." Castro's defense was based on nationalism, the representation and beneficial programs for the non-elite Cubans, and his patriotism and justice for the Cuban community.[29] Fidel was sentenced to 15 years in the Presidio Modelo prison, located on Isla de Pinos, while Raúl was sentenced to 13 years.[30] However, in 1955, under broad political pressure, the Batista government freed all political prisoners in Cuba, including the Moncada attackers. Fidel's Jesuit childhood teachers succeeded in persuading Batista to include Fidel and Raúl in the release.[31]

Soon, the Castro brothers joined with other exiles in Mexico to prepare for the overthrow of Batista, receiving training from Alberto Bayo, a leader of Republican forces in the Spanish Civil War. In June 1955, Fidel met the Argentine revolutionary Ernesto "Che" Guevara, who joined his cause.[31] Raul and Castro's chief advisor Ernesto aided the initiation of Batista's amnesty.[29] The revolutionaries named themselves the "26th of July Movement", in reference to the date of their attack on the Moncada Barracks in 1953.[5]

Guerrilla warfare

While the Castro brothers and the other July 26 Movement guerrillas were training in Mexico and preparing for their amphibious deployment to Cuba, another revolutionary group followed the example of the Moncada Barracks assault. On 29 April 1956 at 12:50 PM during Sunday mass, an independent guerrilla group of around 100 rebels led by Reynol Garcia attacked the Domingo Goicuria army barracks in Matanzas province. The attack was repelled with 10 rebels and 3 soldiers killed in the fighting, and 1 rebel summarily executed by the garrison commander. Florida International University historian Miguel A. Brito was in the nearby Cathedral when the firefight began. He writes, "That day, the Cuban Revolution began for me and Matanzas."[32][33]

The yacht Granma departed from Tuxpan, Veracruz, Mexico, on 25 November 1956, carrying the Castro brothers and 80 others including Ernesto "Che" Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos, even though the yacht was only designed to accommodate 12 people with a maximum of 25. The yacht arrived in Cuba on 2 December.[34] The boat landed in Playa Las Coloradas, in the municipality of Niquero, arriving two days later than planned because the boat was heavily loaded, unlike during the practice sailing runs.[35] This dashed any hopes for a coordinated attack with the llano wing of the Movement. After arriving and exiting the ship, the band of rebels began to make their way into the Sierra Maestra mountains, a range in southeastern Cuba. Three days after the trek began, Batista's army attacked and killed most of the Granma participants – while the exact number is disputed, no more than twenty of the original eighty-two men survived the initial encounters with the Cuban army and escaped into the Sierra Maestra mountains.[36]

The group of survivors included Fidel and Raúl Castro, Che Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos. The dispersed survivors, alone or in small groups, wandered through the mountains, looking for each other. Eventually, the men would link up again – with the help of peasant sympathizers – and would form the core leadership of the guerrilla army. A number of female revolutionaries, including Celia Sanchez and Haydée Santamaría (the sister of Abel Santamaria), also assisted Fidel Castro's operations in the mountains.[37]

On the 13 March 1957, a separate group of revolutionaries – the anticommunist Student Revolutionary Directorate (RD) (Directorio Revolucionario Estudantil, DRE), composed mostly of students – stormed the Presidential Palace in Havana, attempting to assassinate Batista and decapitate the government. The attack ended in utter failure. The RD's leader, student José Antonio Echeverría, died in a shootout with Batista's forces at the Havana radio station he had seized to spread the news of Batista's anticipated death. The handful of survivors included Dr. Humberto Castello (who later became the Inspector General in the Escambray), Rolando Cubela and Faure Chomon (both later Commandantes of the 13 March Movement, centered in the Escambray Mountains of Las Villas Province).[38]

Comandante William Alexander Morgan of the Second National Front of the Escambray

While Batista increased troop deployments to the Sierra Maestra region to crush the 26 July guerrillas, the Second National Front of the Escambray kept battalions of the Constitutional Army tied up in the Escambray Mountains region. The Second National Front was led by former Revolutionary Directorate member Eloy Gutiérrez Menoyo and the "Yanqui Comandante" William Alexander Morgan. Gutiérrez Menoyo formed and headed the guerrilla band after news had broken out about Castro's landing in the Sierra Maestra, and José Antonio Echeverría had stormed the Havana Radio station. Though Morgan was dishonorably discharged from the U.S. Army, his recreating features from Army basic training made a critical difference in the Second National Front troops battle readiness.[39]

Thereafter, the United States imposed an economic embargo on the Cuban government and recalled its ambassador, weakening the government's mandate further.[40] Batista's support among Cubans began to fade, with former supporters either joining the revolutionaries or distancing themselves from Batista. Once Batista started making drastic decisions concerning Cuba's economy, he began to nationalize U.S oil refineries and other U.S properties.[41] Nonetheless, the Mafia and U.S. businessmen maintained their support for the regime.[42][43]

Batista's government often resorted to brutal methods to keep Cuba's cities under control. However, in the Sierra Maestra mountains, Castro, aided by Frank País, Ramos Latour, Huber Matos, and many others, staged successful attacks on small garrisons of Batista's troops. Castro was joined by CIA connected Frank Sturgis who offered to train Castro's troops in guerrilla warfare. Castro accepted the offer, but he also had an immediate need for guns and ammunition, so Sturgis became a gunrunner. Sturgis purchased boatloads of weapons and ammunition from CIA weapons expert Samuel Cummings' International Armament Corporation in Alexandria, Virginia. Sturgis opened a training camp in the Sierra Maestra mountains, where he taught Che Guevara and other 26th of July Movement rebel soldiers guerrilla warfare.

In addition, poorly armed irregulars known as escopeteros harassed Batista's forces in the foothills and plains of Oriente Province. The escopeteros also provided direct military support to Castro's main forces by protecting supply lines and by sharing intelligence.[44] Ultimately, the mountains came under Castro's control.[45]

In addition to armed resistance, the rebels sought to use propaganda to their advantage. A pirate radio station called Radio Rebelde ("Rebel Radio") was set up in February 1958, allowing Castro and his forces to broadcast their message nationwide within enemy territory.[46] Castro's affiliation with the New York Times journalist Herbert Matthews created a front page-worthy report on anti-communist propaganda.[47] The radio broadcasts were made possible by Carlos Franqui, a previous acquaintance of Castro who subsequently became a Cuban exile in Puerto Rico.[48]

Raúl Castro (left), with his arm around his second-in-command, Ernesto "Che" Guevara, in their Sierra de Cristal mountain stronghold in Oriente Province, Cuba, in 1958

During this time, Castro's forces remained quite small in numbers, sometimes fewer than 200 men, while the Cuban army and police force had a manpower of around 37,000.[49] Even so, nearly every time the Cuban military fought against the revolutionaries, the army was forced to retreat. An arms embargo – imposed on the Cuban government by the United States on the 14 March 1958 – contributed significantly to the weakness of Batista's forces. The Cuban air force rapidly deteriorated: it could not repair its airplanes without importing parts from the United States.[50]

Batista finally responded to Castro's efforts with an attack on the mountains called Operation Verano, known to the rebels as la Ofensiva. The army sent some 12,000 soldiers, half of them untrained recruits, into the mountains, along with his own brother Raul. In a series of small skirmishes, Castro's determined guerrillas defeated the Cuban army.[50] In the Battle of La Plata, which lasted from 11 to 21 July 1958, Castro's forces defeated a 500-man battalion, capturing 240 men while losing just three of their own.[51]

However, the tide nearly turned on the 29 July 1958, when Batista's troops almost destroyed Castro's small army of some 300 men at the Battle of Las Mercedes. With his forces pinned down by superior numbers, Castro asked for, and received, a temporary cease-fire on 1 August. Over the next seven days, while fruitless negotiations took place, Castro's forces gradually escaped from the trap. By the 8 August, Castro's entire army had escaped back into the mountains, and Operation Verano had effectively ended in failure for the Batista government.[50]

Final offensive and rebel victory

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

The enemy soldier in the Cuban example which at present concerns us, is the junior partner of the dictator; he is the man who gets the last crumb left by a long line of profiteers that begins in Wall Street and ends with him. He is disposed to defend his privileges, but he is disposed to defend them only to the degree that they are important to him. His salary and his pension are worth some suffering and some dangers, but they are never worth his life. If the price of maintaining them will cost it, he is better off giving them up; that is to say, withdrawing from the face of the guerrilla danger.

— Che Guevara, 1958[52]

Map of Cuba showing the location of the arrival of the rebels on the Granma in late 1956, the rebels' stronghold in the Sierra Maestra, and Guevara and Cienfuegos' route towards Havana via Las Villas Province in December 1958

Map showing key locations in the Sierra Maestra during the 1958 stage of the Cuban Revolution

On 21 August 1958, after the defeat of Batista's Ofensiva, Castro's forces began their own offensive. In the Oriente province (in the area of the present-day provinces of Santiago de Cuba, Granma, Guantánamo and Holguín),[53] Fidel Castro, Raúl Castro and Juan Almeida Bosque directed attacks on four fronts. Descending from the mountains with new weapons captured during the Ofensiva and smuggled in by plane, Castro's forces won a series of initial victories. Castro's major victory at Guisa, and the successful capture of several towns including Maffo, Contramaestre, and Central Oriente, brought the Cauto plains under his control.

Meanwhile, three rebel columns, under the command of Che Guevara, Camilo Cienfuegos and Jaime Vega, proceeded westward toward Santa Clara, the capital of Villa Clara Province. Batista's forces ambushed and destroyed Jaime Vega's column, but the surviving two columns reached the central provinces, where they joined forces with several other resistance groups not under the command of Castro. When Che Guevara's column passed through the province of Las Villas, and specifically through the Escambray Mountains – where the anticommunist Revolutionary Directorate forces (who became known as the 13 March Movement) had been fighting Batista's army for many months – friction developed between the two groups of rebels. Nonetheless, the combined rebel army continued the offensive, and Cienfuegos won a key victory in the Battle of Yaguajay on 30 December 1958, earning him the nickname "The Hero of Yaguajay".

On 31 December 1958, the Battle of Santa Clara took place in a scene of great confusion. The city of Santa Clara fell to the combined forces of Che Guevara, Cienfuegos, and Revolutionary Directorate (RD) rebels led by Comandantes Rolando Cubela, Juan ("El Mejicano") Abrahantes, and William Alexander Morgan. News of these defeats caused Batista to panic. He fled Cuba by air for the Dominican Republic just hours later on 1 January 1959. Comandante William Alexander Morgan, leading RD rebel forces, continued fighting as Batista departed, and had captured the city of Cienfuegos by 2 January.[54]

Castro learned of Batista's flight in the morning and immediately started negotiations to take over Santiago de Cuba. On the 2nd of January, the military commander in the city, Colonel Rubido, ordered his soldiers not to fight, and Castro's forces took over the city. The forces of Guevara and Cienfuegos entered Havana at about the same time. They had met no opposition on their journey from Santa Clara to Cuba's capital. Castro himself arrived in Havana on 8 January after a long victory march. His initial choice of president, Manuel Urrutia Lleó, took office on 3 January.[55]

Women's roles in the revolution

Raúl Castro, Vilma Espín, Jorge Risquet and José Nivaldo Causse in 1958

The importance of women's contributions to the Cuban Revolution is reflected in the very accomplishments that allowed the revolution to be successful, from the participation in the Moncada Barracks, to the Mariana Grajales all-women's platoon that served as Fidel Castro's personal security detail. Tete Puebla, second in command of the Mariana Grajales Platoon, has said:

Women in Cuba have always been on the front line of the struggle. At Moncada we had Yeye (Haydee Santamaria) and Melba (Hernandez). With the Granma (yacht) and November 30, we had Celia, Vilma, and many other compañeras. There were many women comrades who were tortured and murdered. From the beginning there were women in the Revolutionary Armed Forces. First they were simple soldiers, later sergeants. Those of us in the Mariana Grajales Platoon were the first officers. The ones who ended the war with officers' ranks stayed in the armed forces.[56]

Before the Mariana Grajales Platoon was established, the revolutionary women of the Sierra Maestra were not organized for combat and primarily helped with cooking, mending clothes, and tending to the sick, frequently acting as couriers, as well as teaching guerillas to read and write.[57]

Haydée Santamaría and Melba Hernandez were the only women who participated in the attack on the Moncada Barracks, afterward acting alongside Natalia Revuelta, and Lidia Castro (Fidel Castro's sister) to form alliances with anti-Batista organizations, as well as the assembly and distribution of "History Will Absolve Me".[58]Celia Sanchez and Vilma Espin were leading strategists and highly skilled combatants who held essential roles throughout the revolution. Tete Puebla, founding member and second in command of the Mariana Grajales Platoon, said of Celia Sanchez, "When you speak of Celia, you've got to speak of Fidel, and vice versa. Celia's ideas touched almost everything in the Sierra.[56]

Aftermath

Our revolution is endangering all American possessions in Latin America. We are telling these countries to make their own revolution.

— Che Guevara, October 1962[59]

Fidel Castro during a visit to Washington, D.C., shortly after the Cuban Revolution in 1959

On 15 April 1959, Castro began an 11-day visit to the United States, at the invitation of the American Society of Newspaper Editors.[60] He said during his visit: "I know the world thinks of us, we are Communists, and of course I have said very clear that we are not Communists; very clear."[61]

Hundreds of Batista-era agents, policemen and soldiers were put on public trial, accused of human rights abuses, war crimes, murder, and torture. About 200 of the accused people were convicted of political crimes by revolutionary tribunals and then executed by firing squad; others received long sentences of imprisonment. A notable example of revolutionary justice occurred after the capture of Santiago, where Raúl Castro directed the execution of more than seventy Batista POWs.[62] For his part in taking Havana, Che Guevara was appointed supreme prosecutor in La Cabaña Fortress. This was part of a large-scale attempt by Fidel Castro to cleanse the security forces of Batista loyalists and potential opponents of the new revolutionary government. Though many were killed or imprisoned, others were fortunate enough to be dismissed from the army and police without prosecution, and some high-ranking officials of the Batista administration were exiled as military attachés.[62] Most scholars agree that those executed were probably guilty as accused, but the trials did not follow due process.[63]

Reforms and nationalization

During its first decade in power, the Castro government introduced a wide range of progressive social reforms. Laws were introduced to provide equality for black Cubans and greater rights for women, while there were attempts to improve communications, medical facilities, health, housing, and education. In addition, there were touring cinemas, art exhibitions, concerts, and theatres. By the end of the 1960s, all Cuban children were receiving some education (compared with less than half before 1959), unemployment and corruption were reduced, and great improvements were made in hygiene and sanitation.[64] Fidel dedicated many of his years to the equality among Afro-Cubans and the wealthy white people of Cuba. His anti-discrimination legislation was his first and major attempt to give equality to the people of Cuba. His many reforms (healthcare, education, and equality) gave opportunities to those Afro-Cubans who lived in poverty because of the racial discrimination in Cuba.[65]

The equal right of all citizens to health, education, work, food, security, culture, science, and wellbeing - that is, the same rights we proclaimed when we began our struggle, in addition to those which emerge from our dreams of justice and equality for all inhabitants of our world - is what I wish for all.

— Fidel Castro[66]

Castro's government was entirely based on his ideologies of equality and fair measures for the people of Cuba. After he considered to have done everything in his power toward equality, he passed a legislation that counter-attacked his past anti-discrimination legislation. This law made it illegal to even mention discrimination or the topic of equality.[65]

Fidel Castro (far left) and Che Guevara (centre) lead a memorial march in Havana on 5 March 1960 for the victims of the La Coubre freight ship explosion

According to geographer and Cuban Comandante Antonio Núñez Jiménez, 75% of Cuba's best arable land was owned by foreign individuals or foreign (mostly American) companies at the time of the revolution. One of the first policies of the newly formed Cuban government was eliminating illiteracy and implementing land reforms. Land reform efforts helped to raise living standards by subdividing larger holdings into cooperatives. Comandante Sori Marin, who was nominally in charge of land reform, objected and fled, but was eventually executed when he returned to Cuba with arms and explosives, intending to overthrow the Castro government.[67][68]

Shortly after taking power, Castro also created a revolutionary militia to expand his power base among the former rebels and the supportive population. Castro also created the informant Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDRs) in late September 1960. Local CDRs were tasked with keeping "vigilance against counter-revolutionary activity", keeping a detailed record of each neighborhood's inhabitants' spending habits, level of contact with foreigners, work and education history, and any "suspicious" behavior.[69] Among the increasingly persecuted groups were homosexual men.[70]

In February 1959, the Ministry for the Recovery of Misappropriated Assets (Ministerio de Recuperación de Bienes Malversados) was created. Cuba began expropriating land and private property under the auspices of the Agrarian Reform Law of 17 May 1959. Farms of any size could be and were seized by the government, while land, businesses, and companies owned by upper- and middle-class Cubans were nationalized (notably, including the plantations owned by Fidel Castro's family). By the end of 1960, the revolutionary government had nationalized more than $25 billion worth of private property owned by Cubans.[11] The Castro government formally nationalized all foreign-owned property, particularly American holdings, in the nation on 6 August 1960.[12]

In 1961, the Cuban government nationalized all property held by religious organizations, including the dominant Roman Catholic Church. Hundreds of members of the church, including a bishop, were permanently expelled from the nation, as the new Cuban government declared itself officially atheist. Education also saw significant changes – private schools were banned and the progressively socialist state assumed greater responsibility for children.[71] The Cuban government also began to expropriate from mafia leaders and taking millions in cash. Before Meyer Lansky fled Cuba, he was said to be worth an estimated $20M, that would be $163,685,121 in 2016. When he died in 1983, his family was shocked that his estate was worth less than $10K. Before he died Lansky said Cuba "ruined" him.[72]

In July 1961, the Integrated Revolutionary Organizations (IRO) was formed by the merger of Fidel Castro's 26th of July Movement, the People's Socialist Party led by Blas Roca, and the Revolutionary Directorate of 13 March led by Faure Chomón.[73]

On 26 March 1962, the IRO became the United Party of the Cuban Socialist Revolution (PURSC) which, in turn, became the modern Communist Party of Cuba on 3 October 1965, with Castro as First Secretary. Castro remained the ruler of Cuba, first as Prime Minister and, from 1976, as President, until his retirement in February 20, 2008.[74] His brother Raúl officially replaced him as President later that same month.[75]

International reactions and foreign policy

I believe that there is no country in the world, including the African regions, including any and all the countries under colonial domination, where economic colonization, humiliation and exploitation were worse than in Cuba, in part owing to my country's policies during the Batista regime. I believe that we created, built and manufactured the Castro movement out of whole cloth and without realizing it. I believe that the accumulation of these mistakes has jeopardized all of Latin America. The great aim of the Alliance for Progress is to reverse this unfortunate policy. This is one of the most, if not the most, important problems in America foreign policy. I can assure you that I have understood the Cubans. I approved the proclamation which Fidel Castro made in the Sierra Maestra, when he justifiably called for justice and especially yearned to rid Cuba of corruption. I will go even further: to some extent it is as though Batista was the incarnation of a number of sins on the part of the United States. Now we shall have to pay for those sins. In the matter of the Batista regime, I am in agreement with the first Cuban revolutionaries.

— U.S. President John F. Kennedy, interview with Jean Daniel, 24 October 1963[76]

.mw-parser-output .quotebox{background-color:#F9F9F9;border:1px solid #aaa;box-sizing:border-box;padding:10px;font-size:88%}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft{margin:0.5em 1.4em 0.8em 0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright{margin:0.5em 0 0.8em 1.4em}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.centered{margin:0.5em auto 0.8em auto}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft p,.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright p{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-title{background-color:#F9F9F9;text-align:center;font-size:larger;font-weight:bold}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:before{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" “ ";vertical-align:-45%;line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:after{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" ” ";line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .left-aligned{text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .right-aligned{text-align:right}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .center-aligned{text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .quotebox cite{display:block;font-style:normal}@media screen and (max-width:360px){.mw-parser-output .quotebox{min-width:100%;margin:0 0 0.8em!important;float:none!important}}

-– Walter Lippmann, Newsweek, 27 April 1964[77]

The Cuban Revolution was a crucial turning point in U.S.-Cuban relations. Although the United States government was initially willing to recognize Castro's new government,[78] it soon came to fear that Communist insurgencies would spread through the nations of Latin America, as they had in Southeast Asia.[79] Castro, meanwhile, resented the Americans for providing aid to Batista's government during the revolution.[78] After the revolutionary government nationalized all U.S. property in Cuba in August 1960, the American Eisenhower administration froze all Cuban assets on American soil, severed diplomatic ties and tightened its embargo of Cuba.[7][12][80] The Key West–Havana ferry shut down. In 1961, the U.S. government backed an armed counterrevolutionary assault on the Bay of Pigs with the aim of ousting Castro, but the counterrevolutionaries were swiftly defeated by the Cuban military.[79] The U.S. Embargo against Cuba – the longest-lasting single foreign policy in American history[81] – is still in force as of 2018, although it has undergone a partial loosening in recent years, only to be recently strengthened in 2017.[7] The U.S. began efforts to normalize relations with Cuba in the mid-2010s,[9][82] and formally reopened its embassy in Havana after over half a century in August 2015.[10]

Propaganda poster in Havana, 2012

Castro's victory and post-revolutionary foreign policy had global repercussions. Influenced by the expansion of the Soviet Union into Europe after the 1917 Russian Revolution, Castro immediately sought to "export" his revolution to other countries in the Caribbean and beyond, sending weapons to Algerian rebels as early as 1960.[13] In the following decades, Cuba became heavily involved in supporting Communist insurgencies and independence movements in many developing countries, sending military aid to insurgents in Ghana, Nicaragua, Yemen and Angola, among others.[13] Castro's intervention in the Angolan Civil War in the 1970s and 1980s was particularly significant, involving as many as 60,000 Cuban soldiers.[13][83]

Following the American embargo, the Soviet Union became Cuba's main ally.[12] The two Communist countries quickly developed close military and intelligence ties, culminating in the stationing of Soviet nuclear weapons in Cuba in 1962, an act which triggered the Cuban Missile Crisis. Cuba maintained close links to the Soviets until the Soviet Union's collapse in 1991. The end of Soviet economic aid led to an economic crisis and famine known as the Special Period in Cuba.[84]

Exiles and counterrevolutionary rebels

Luis Posada Carriles

In the wake of the revolution, thousands of disaffected anti-Batista rebels, former Batista supporters, and campesinos (peasants) fled to Cuba's Las Villas province, where an anticommunist underground had been forming since early 1960. Operating out of the Escambray Mountains, these counterrevolutionary rebels, also known as Alzados, made a number of unsuccessful attempts to overthrow the Cuban government, including the abortive, United States-backed Bay of Pigs Invasion of 1961.[79] In the aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, the United States promised not to invade Cuba in the future; in compliance with this agreement, the U.S. withdrew all support from the Alzados, effectively crippling the resource-starved resistance.[85] The counterrevolutionary conflict, known abroad as the Escambray Rebellion, lasted until about 1965, and has since been branded the War Against the Bandits by the Cuban government.[85]

Luis Posada and CORU are widely considered responsible for the 1976 bombing of a Cuban airliner that killed 73 people.[86][87]

Between 1959 and 1980, an estimated 500,000 Cubans left the island for the United States, for both political and economic reasons; 125,000 left in 1980 alone, when the Cuban government briefly permitted any Cubans who wished to leave to do so.[88] By 2010, the Cuban American community numbered over 1.9 million, 67% of whom lived in the state of Florida.[89] As a voting bloc, Cuban Americans have traditionally been strongly opposed to ending the U.S. embargo of Cuba, but in recent years there has been growing support for diplomatic engagement among the younger generations.[90]

In popular culture

- The Cuban Revolution, including Batista's resignation and flight into exile, plays a major role in the plot of the 1974 film The Godfather Part II.[91]

- The 1987 video game Guevara, released in the United States as Guerrilla War, features Castro and Guevara fighting in the jungle against the forces of an unnamed dictator.[92][93]

- The Cuban dissident and exile Reinaldo Arenas wrote about Castro's persecution of homosexuals in his 1992 autobiography Antes Que Anochezca, which became the basis for the 2000 film Before Night Falls.[94]

Steven Soderbergh's 2008 film Che, a two-part biopic about Che Guevara, depicts the rise of Castro's movement and Guevara's role in the Cuban Revolution.[95]

- The 2010 video game Call of Duty: Black Ops features a level set in Havana in 1961, in which players must attempt to assassinate Castro. The level was condemned by the Cuban government.[96]

- The 2013 strategic board game Cuba Libre by US wargaming publisher GMT Games puts players into the roles of the involved parties in the Revolution and lets them reenact the conflict alongside a randomized storyline of the key historical events.[97][98]

See also

- Communist revolution

- Cuban thaw

- History of Cuba

- Latin American wars of independence

References

^ Jacob Bercovitch and Richard Jackson (1997). International Conflict: A Chronological Encyclopedia of Conflicts and Their Management, 1945–1995. Congressional Quarterly.

^ Singer, Joel David and Small, Melvin (1974). The Wages of War, 1816–1965. Inter-University Consortium for Political Research.

^ Eckhardt, William, in Sivard, Ruth Leger (1987). World Military and Social Expenditures, 1987–88 (12th edition). World Priorities.

^ https://havanatimes.org/?p=123355

^ abc Faria, Miguel A., Jr. (27 July 2004). "Fidel Castro and the 26th of July Movement". Newsmax Media. Retrieved 14 August 2015..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "Cuba Marks 50 Years Since 'Triumphant Revolution'". Jason Beaubien. NPR. 1 January 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

^ abc "Cuba receives first US shipment in 50 years". Al Jazeera. 14 July 2012. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

^ "On Cuba Embargo, It's the U.S. and Israel Against the World – Again". New York Times. 28 October 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

^ ab "Cuba off the U.S. terrorism list: Goodbye to a Cold War relic". Los Angeles Times. 17 April 2015. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

^ ab "US flag raised over reopened Cuba embassy in Havana". BBC News. 15 August 2015. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

^ ab Lazo, Mario (1970). American Policy Failures in Cuba – Dagger in the Heart. Twin Circle Publishing Co.: New York. pp. 198–200, 204. Library of Congress Card Catalog Number: 68-31632.

^ abcd Gary B. Nash, Julie Roy Jeffrey, John R. Howe, Peter J. Frederick, Allen F. Davis, Allan M. Winkler, Charlene Mires and Carla Gardina Pestana. The American People, Concise Edition: Creating a Nation and a Society, Combined Volume (6th edition, 2007). New York: Longman.

^ abcd "Makers of the Twentieth Century: Castro". History Today. 1981. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

^ "From the archive, 11 March 1962: Batista's revolution". The Guardian. 11 March 2013. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

^ ab Julia E. Sweig (2004). Inside the Cuban Revolution. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01612-5.

^ Arthur Meier Schlesinger (1973). The Dynamics of World Power: A Documentary History of the United States Foreign Policy 1985–1993. McGraw-Hill. p. 512. ISBN 0-07-079729-3.

^ abc "Remarks of Senator John F. Kennedy at Democratic Dinner, Cincinnati, Ohio, October 6, 1960". John F. Kennedy Presidential Library. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

^ "Fulgencio Batista". HistoryOfCuba.com. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

^ Díaz-Briquets, Sergio & Pérez-López, Jorge F. (2006). Corruption in Cuba: Castro and beyond. University of Texas Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-292-71482-3.CS1 maint: Uses authors parameter (link)

^ New Republic, 14 Dec. 1963, Jean Daniel "Unofficial Envoy: An Historic Report from Two Capitals," page 16 US President John F. Kennedy said: "I approved the proclamation which Fidel Castro made in the Sierra Maestra, when he justifiably called for justice and especially yearned to rid Cuba of corruption. I will even go further: to some extent it is as though Batista was the incarnation of a number of sins on the part of the United States. Now we shall have to pay for those sins. In the matter of the Batista regime, I am in agreement with the first Cuban revolutionaries."

^ James Stuart Olson (2000). Historical Dictionary of the 1950s. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 67–68. ISBN 0-313-30619-2.

^ "Biography of Fidel Castro". About.com. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

^ Bourne, Peter G. (1986). Fidel: A Biography of Fidel Castro. New York City: Dodd, Mead & Company. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-0-396-08518-8.

^ "Historical sites: Moncada Army Barracks and". CubaTravelInfo. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

^ Hunt, Michael H. (2004). The World Transformed: 1945 to the present. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 257. ISBN 9780199371020.

^ Castro (2007), p. 133

^ Hunt, Michael (2014). The World Transformed 1945 to the Present. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 257.

^ Castro (2007), p. 672

^ ab Hunt, Michael (2014). The World Transformed 1945 to the Present. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 258.

^ "Chronicle of an Unforgettable Agony: Cuba's Political Prisons". Contacto Magazine. September 1996. Archived from the original on 28 January 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

^ ab Castro (2007), p. 174

^ {{cite web|title=Uprising In Cuba Quickly Quelled, Ten Listed Dead|url=https://newspaperarchive.com/florence-morning-news-apr-30-1956-p-1/%7Cpublisher=Florence Morning News|accessdate=25 Jan 2019

^ "Finally, Cuba's Matanzas gets some respect". Victoria Advocate. Retrieved 5 May 2010....the world knows about the Moncada attack in Oriente province that made Fidel Castro famous, but few have heard of the attack on the Goicuria Barracks in Matanzas on April 29, 1956. That event caught the young Bretos on a Sunday outing to mass at the cathedral with his Aunt Nena. He remembers the scene vividly: the staccato gun fire, the military fighter that roared by, the news that all the rebels had been killed, the photographs of the colonel in charge who smiled proudly over the corpses and of a prisoner being shot in cold blood, the latter image published in the Spanish edition of Life. "That day," Bretos writes, "the Cuban Revolution began for me and Matanzas."

^ "Cuban Revolution: The Voyage of the Granma". Latin American History. Retrieved 24 December 2014.The yacht, designed for only 12 passengers and supposedly with a maximum capacity of 25, also had to carry fuel for a week as well as food and weapons for the soldiers.

^ Castro (2007), p. 182

^ Thomas (1998)

^ "Opiniones: Haydee Santamaría, una mujer revolucionaria" (in Spanish). La Ventana. 2 July 2004. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

^ Faria (2002), pp. 40–41

^ American Comandante, 2015 episode of American Experience

^ Louis A. Pérez. Cuba and the United States.

^ Hunt, Michael (2014). The World Transformed 1945 to the Present. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 260.

^ English (2008)[page needed]

^ "The Batista-Lansky Alliance: How the mafia and a Cuban dictator built Havana's casinos". Cigar Aficionado. May 2001. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

^ Dewitt, Don A. (2011). U.S. Marines at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. iUniverse via Google Books. p. 31.

^ Mallin, Jay (2018). Covering Castro: Rise and Decline of Cuba's Communist Dictator. New York: Taylor & Francis. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-351-29418-8.

^ "About Us". Radio Rebelde. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

^ Hunt, Michael (2014). The World Transformed 1945 to the Present. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 267. ISBN 9780199371020.

^ "Carlos Franqui". Daily Telegraph. 24 May 2010. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

^ "Batista Says Manpower Edge Lacking". Park City Daily News. Google News Archive. 1 January 1959. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

^ abc "Air war over Cuba 1956–1959". ACIG.org. 30 November 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

^ "1958: Battle of La Plata (El Jigüe)". Cuba 1952–1959. 15 December 2009. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

^ The Life & Times of Che Guevara by David Sandison (1996). Paragon.

ISBN 0-7525-1776-7. p. 41.

^ Brown & Tucker (2013), p. 127

^ Faria (2002), p. 69

^ Thomas (1998), pp. 691–93

^ ab Puebla, Teté, and Mary-Alice Waters. Marianas in Combat: Teté Puebla & the Mariana Grajales Women's Platoon in Cuba's Revolutionary War, 1956-58. New York: Pathfinder, 2003.

^ Puebla, Teté, and Mary-Alice Waters. Marianas in Combat: Teté Puebla & the Mariana Grajales Women's Platoon in Cuba's Revolutionary War, 1956-58. New York: Pathfinder, 2003

^ Shayne, Julie D. The Revolution Question: Feminisms in El Salvador, Chile, and Cuba. Rutgers University Press, 2004.

^ "Attack us at your Peril, Cocky Cuba Warns US". Henry Brandon. The Sunday Times. 28 October 1962. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

^ Glass, Andrew (15 April 2013). "Fidel Castro visits the U.S., April 15, 1959". Politico. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

^ "Cuban Revolution". 1959 Year in Review. United Press International. 1959. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

^ ab Clark (1992), pp. 53–70

^ Chase, Michelle (2010). "The Trials". In Greg Grandin; Joseph Gilbert. A Century of Revolution. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. pp. 163–98. ISBN 0822347377. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

^ Mastering Modern World History by Norman Lowe, second edition.

^ ab Espina, Rodrigo (March 2006). "Raza y desigualdad en Cuba actual" (PDF).

^ "Fidel Castro Quotes".

^ Font (1995), pp. 80-81

^ Lazo (1968), pp. 288

^ Clark (1992), pp. 131–158

^ Young, Allen (1982). Gays under the Cuban revolution. Grey Fox Press. ISBN 0-912516-61-5.

^ Faria (2002), pp. 215–28

^ "Fidel Castro a mixed legacy that includes fighting the mafia". 26 November 2016.

^ Kantor, Myles B. (14 June 2002). "Interview With Dr. Miguel Faria (Part I)". Newsmax Media. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

^ "Fidel Castro Resigns as Cuba's President". New York Times. 20 February 2008. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

^ "Raúl Castro becomes Cuban president". New York Times. 24 February 2008. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

^ "Jean Daniel Bensaid: Biography" . Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

^ "Cuba Once More" by Walter Lippmann. Newsweek. 27 April 1964. p. 23.

^ ab Gleijeses, Piero (2002). Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington and Africa, 1959–1976. University of North Carolina Press. p. 14.

^ abc "Ahead Of Bay Of Pigs, Fears Of Communism". NPR. 17 April 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

^ Faria (2002), p. 105

^ "Washington and the Cuban Revolution Today: Ballad of a Never-Ending Policy – Part I: The Myth of the Miami Lobby". Dissident Voice. 22 June 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

^ "Obama hails 'new chapter' in US-Cuba ties". BBC News. 17 December 2014. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

^ "La Guerras Secretas de Fidel Castro" Archived 18 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish). CubaMatinal.com. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

^ "Parrot diplomacy". The Economist. 24 July 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

^ ab "Cuba: Intelligence and the Bay of Pigs". Stanford University. 26 September 2002. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

^ Bardach, Ann Louis; Rohter, Larry (July 13, 1998). "A Bomber's Tale: Decades of Intrigue". The New York Times. The New York Times Company.

^ Lettieri, Mike (June 1, 2007). "Posada Carriles, Bush's Child of Scorn". Washington Report on the Hemisphere. 27 (7/8).

^ "Cuban Exile Community". LatinAmericanStudies.org. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

^ "Hispanics of Cuban Origin in the United States, 2010". Pew Research. 27 June 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

^ "Latino millennials want to end Cuba embargo". CNN. 24 October 2012. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

^ "Film locations for The Godfather Part 2 (1974)". Movie-Locations.com. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

^ Scott Sharkey. "EGM's Top Ten Videogame Politicians: Election time puts us in a voting mood". Electronic Gaming Monthly 234 (November 2008): 97.

^ "Guerrilla War/Guevara". Hardcore Gaming 101. 18 October 2013. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

^ "Antes Que Anochezca = Before Night Falls". Publishers Weekly. 3 February 1992. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

^ "Che: Part One". The Observer. 4 January 2009. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

^ "Call of Duty: Black Ops upsets Cuba with Castro mission". The Guardian. 11 November 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

^ "Cuba Libre". GMT Games. Archived from the original on 18 April 2014. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

^ "Cuba Libre". BoardGameGeek.com. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

Bibliography

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Brown, Gates; Tucker, Spencer C. (2013). "Cuban Revolution". In Tucker, Spencer C. Encyclopedia of Insurgency and Counterinsurgency: A New Era of Modern Warfare: A New Era of Modern Warfare. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-280-9.

Castro, Fidel (2007). Ignacio Ramonet, ed. Fidel Castro: My Life. Translated by Andrew Hurley. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-102626-8.

Clark, Juan (1992). Cuba: Mito y Realidad: Testimonios de un Pueblo. Miami: Saeta Ediciones. ISBN 978-0-917049-16-3.

English, T. J. (2008). Havana Nocturne: How the Mob Owned Cuba and Then Lost It to the Revolution. William Morrow. ISBN 0-06-114771-0.

Font, Fabián Escalante (1995). The Secret War: CIA Covert Operations Against Cuba, 1959-62. Ocean Front. ISBN 1875284869.

Faria, Miguel A., Jr. (2002). Cuba in Revolution: Escape from a Lost Paradise. Milledgeville, GA: Hacienda Pub Inc. ISBN 0-9641077-3-2.

Lazo, Mario (1968). Dagger in the heart: American policy failures in Cuba. New York: Twin Circle.

Thomas, Hugh (1998). Cuba: The Pursuit of Freedom. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80827-7.

Further reading

- Thomas M. Leonard (1999). Castro and the Cuban Revolution. Greenwood Press.

ISBN 0-313-29979-X. - Julio García Luis (2008). Cuban Revolution Reader: A Documentary History of Key Moments in Fidel Castro's Revolution. Ocean Press.

ISBN 1-920888-89-6.

Samuel Farber (2012). Cuba Since the Revolution of 1959: A Critical Assessment. Haymarket Books.

ISBN 9781608461394.

Joseph Hansen (1994). Dynamics of the Cuban Revolution: A Marxist Appreciation. Pathfinder Press.

ISBN 0-87348-559-9.

Julia E. Sweig (2004). Inside the Cuban Revolution: Fidel Castro and the Urban Underground. Harvard University Press.

ISBN 0-674-01612-2.

Thomas C. Wright (2000). Latin America in the Era of the Cuban Revolution. Praeger Paperback.

ISBN 0-275-96706-9.- Marifeli Perez-Stable (1998). The Cuban Revolution: Origins, Course, and Legacy. Oxford University Press.

ISBN 0-19-512749-8. - Geraldine Lievesley (2004). The Cuban Revolution: Past, Present and Future Perspectives. Palgrave Macmillan.

ISBN 0-333-96853-0.

Teo A. Babun (2005). The Cuban Revolution: Years of Promise. University Press of Florida.

ISBN 0-8130-2860-4.- Antonio Rafael de la Cova (2007). The Moncada Attack: Birth of the Cuban Revolution. University of South Carolina Press.

ISBN 1-57003-672-1. - Samuel Farber (2006). The Origins of the Cuban Revolution Reconsidered. The University of North Carolina Press.

ISBN 0-8078-5673-8. - Jules R. Benjamin (1992). The United States and the Origins of the Cuban Revolution. Princeton University Press.

ISBN 0-691-02536-3. - Comite central del Partido comunista de Cuba: Comisión de orientación revolucionaria (1972). Rencontre symbolique entre deux processus historiques [i.e., de Cuba et de Chile]. La Habana, Cuba: Éditions politiques.

- David M. Watry (2014). Diplomacy at the Brink: Eisenhower, Churchill, and Eden in the Cold War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

ISBN 9780807157183.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cuban Revolution. |

- Fidel Castro. "What Cuba's Rebels Want" at Archive.today (archived 17 April 2009). The Nation via Internet Archive. 30 November 1957.

"The Cuban Revolution (1952–1958)". Latin American Studies Organization.- Michael Voss. "Reliving Cuba's Revolution". BBC. 29 December 2008.

"The History of Socialist Revolution in Cuba (1953–1959)". World History Archives.- Arthur Brice. "Memories of Boyhood in the Heat of the Cuban Revolution". CNN. 2009.

"1959 – 2009: Celebrating 50 years of the Cuban Revolution". Cuba Solidarity Campaign.- A film clip "Castro Triumphs. Havana Crowds Hail Success Of Revolt, 1959/01/05 (1959)" is available at the Internet Archive.

Comments

Post a Comment