London Bridge

Coordinates: 51°30′29″N 0°05′16″W / 51.50806°N 0.08778°W / 51.50806; -0.08778

London Bridge | |

|---|---|

London Bridge in January 2006 | |

| Coordinates | 51°30′29″N 0°05′16″W / 51.50806°N 0.08778°W / 51.50806; -0.08778 |

| Carries | Five lanes of the A3 |

| Crosses | River Thames |

| Locale | Central London |

| Maintained by | Bridge House Estates, City of London Corporation |

| Preceded by | Cannon Street Railway Bridge |

| Followed by | Tower Bridge |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Prestressed concrete box girder bridge |

| Total length | 269 m (882.5 ft) |

| Width | 32 m (105.0 ft) |

| Longest span | 104 m (341.2 ft) |

| Clearance below | 8.9 m (29.2 ft) |

| Design life | Modern bridge (1971–present) Victorian stone arch (1832–1968) Medieval stone arch (1176–1832) Various wooden bridges (AD 50–1176) |

| History | |

| Opened | 17 March 1973 (1973-03-17) |

Several bridges named London Bridge have spanned the River Thames between the City of London and Southwark, in central London. The current crossing, which opened to traffic in 1973, is a box girder bridge built from concrete and steel. It replaced a 19th-century stone-arched bridge, which in turn superseded a 600-year-old stone-built medieval structure. This was preceded by a succession of timber bridges, the first of which was built by the Roman founders of London.

The current bridge stands at the western end of the Pool of London and is positioned 30 metres (98 ft) upstream from previous alignments. The approaches to the medieval bridge were marked by the church of St Magnus-the-Martyr on the northern bank and by Southwark Cathedral on the southern shore. Until Putney Bridge opened in 1729, London Bridge was the only road-crossing of the Thames downstream of Kingston upon Thames. London Bridge has been depicted in its several forms, in art, literature, and songs, including the nursery rhyme "London Bridge Is Falling Down".

The modern bridge is owned and maintained by Bridge House Estates, an independent charity of medieval origin overseen by the City of London Corporation. It carries the A3 road, which is maintained by the Greater London Authority.[1] The crossing also delineates an area along the southern bank of the River Thames, between London Bridge and Tower Bridge, that has been designated as a business improvement district.[2]

Contents

1 History

1.1 Location

1.2 Roman bridges

1.3 Early medieval bridges

1.4 "Old" London Bridge (1209–1831)

1.5 "New" London Bridge (1831–1967)

1.5.1 Sale to Robert McCulloch

1.6 Modern London Bridge

2 Transport

3 London Bridge in literature and popular culture

4 See also

5 Notes

6 References

7 External links

History

Location

The abutments of modern London Bridge rest several metres above natural embankments of gravel, sand and clay. From the late Neolithic era the southern embankment formed a natural causeway above the surrounding swamp and marsh of the river's estuary; the northern ascended to higher ground at the present site of Cornhill. Between the embankments, the River Thames could have been crossed by ford when the tide was low, or ferry when it was high. Both embankments, particularly the northern, would have offered stable beachheads for boat traffic up and downstream – the Thames and its estuary were a major inland and Continental trade route from at least the 9th century BC.[3]

There is archaeological evidence for scattered Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age settlement nearby, but until a bridge was built there, London did not exist.[4]A few miles upstream, beyond the river's upper tidal reach, two ancient fords were in use. These were apparently aligned with the course of Watling Street, which led into the heartlands of the Catuvellauni, Britain's most powerful tribe at the time of Caesar's invasion of 54 BC. Some time before Claudius's conquest of AD 43, power shifted to the Trinovantes, who held the region northeast of the Thames Estuary from a capital at Camulodunum, nowadays Colchester in Essex. Claudius imposed a major colonia on Camulodunum, and made it the capital city of the new Roman province of Britannia. The first London Bridge was built by the Romans as part of their road-building programme, to help consolidate their conquest.[5]

Roman bridges

The first bridge was probably a Roman military pontoon type, giving a rapid overland shortcut to Camulodunum from the southern and Kentish ports, along the Roman roads of Stane Street and Watling Street (now the A2). Around 55 AD, the temporary bridge over the Thames was replaced by a permanent timber piled bridge, maintained and guarded by a small garrison. On the relatively high, dry ground at the northern end of the bridge, a small, opportunistic trading and shipping settlement took root and grew into the town of Londinium.[6] A smaller settlement developed at the southern end of the bridge, in the area now known as Southwark. The bridge was probably destroyed along with the town in the Boudican revolt (60 AD), but both were rebuilt and Londinium became the administrative and mercantile capital of Roman Britain. The upstream fords and ferries remained in use but the bridge offered uninterrupted, mass movement of foot, horse, and wheeled traffic across the Thames, linking four major arterial road systems north of the Thames with four to the south. Just downstream of the bridge were substantial quays and depots, convenient to seagoing trade between Britain and the rest of the Roman Empire.[7][8]

Early medieval bridges

With the end of Roman rule in Britain in the early 5th century, Londinium was gradually abandoned and the bridge fell into disrepair. In the Anglo-Saxon period, the river became a boundary between the emergent, mutually hostile kingdoms of Mercia and Wessex. By the late 9th century, Danish invasions prompted at least a partial reoccupation of the site by the Saxons. The bridge may have been rebuilt by Alfred the Great soon after the Battle of Edington as part of Alfred's redevelopment of the area in his system of burhs,[9] or it may have been rebuilt around 990 under the Saxon king Æthelred the Unready to hasten his troop movements against Sweyn Forkbeard, father of Cnut the Great. A skaldic tradition describes the bridge's destruction in 1014 by Æthelred's ally Olaf,[10] to divide the Danish forces who held both the walled City of London and Southwark. The earliest contemporary written reference to a Saxon bridge is c.1016 when chroniclers mention how Cnut's ships bypassed the crossing, during his war to regain the throne from Edmund Ironside (see Battle of Brentford (1016)).

Following the Norman conquest in 1066, King William I rebuilt the bridge. The London tornado of 1091 destroyed it, also damaging St Mary-le-Bow.[11] It was repaired or replaced by King William II, destroyed by fire in 1136, and rebuilt in the reign of Stephen. Henry II created a monastic guild, the "Brethren of the Bridge", to oversee all work on London Bridge. In 1163 Peter of Colechurch, chaplain and Warden of the bridge and its Brethren, supervised the bridge's last rebuilding in timber.[12]

"Old" London Bridge (1209–1831)

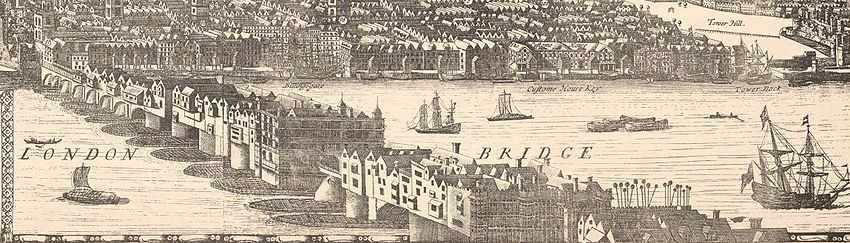

An engraving by Claes Visscher showing Old London Bridge in 1616, with what is now Southwark Cathedral in the foreground. The spiked heads of executed criminals can be seen above the Southwark gatehouse.

After the murder of his erstwhile friend and later opponent Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury, the penitent King Henry II commissioned a new stone bridge in place of the old, with a chapel at its centre dedicated to Becket as martyr. The archbishop had been a native Londoner and a popular figure. The Chapel of St Thomas on the Bridge became the official start of pilgrimage to his Canterbury shrine; it was grander than some town parish churches, and had an additional river-level entrance for fishermen and ferrymen. Building work began in 1176, supervised by Peter of Colechurch.[12] The costs would have been enormous; Henry's attempt to meet them with taxes on wool and sheepskins probably gave rise to a later legend that London Bridge was built on wool packs.[12] It was finished by 1209 during the reign of King John; it had taken 33 years to complete. John tried to recoup the cost of building and maintenance by licensing out building plots on the bridge but this was never enough. In 1284, in exchange for loans to Edward I, the City of London acquired the Charter for the maintenance of the bridge, based on the duties and toll-rights of the former "Brethren of the Bridge".

The bridge was 26 feet (8 m) wide, and about 800–900 feet (240–270 m) long, supported by 19 irregularly spaced arches, founded on starlings set into the river-bed. It had a drawbridge to allow for the passage of tall ships, and defensive gatehouses at both ends. By 1358 it was already crowded with 138 shops. At least one two-entranced, multi-seated public latrine overhung the bridge parapets and discharged into the river below; so did an unknown number of private latrines reserved for Bridge householders or shopkeepers and bridge officials. In 1382–83 a new latrine was made (or an old one replaced) at considerable cost, at the northern end of the bridge.[13]

The buildings on London Bridge were a major fire hazard and increased the load on its arches, several of which had to be rebuilt over the centuries. In 1212, perhaps the greatest of the early fires of London broke out on both ends of the bridge simultaneously, trapping many people in the middle. Houses on the bridge were burnt during Wat Tyler's Peasants' Revolt in 1381 and during Jack Cade's rebellion in 1450. A major fire of 1633 that destroyed the northern third of the bridge formed a firebreak that prevented further damage to the bridge during the Great Fire of London (1666).

By the Tudor period there were some 200 buildings on the bridge. Some stood up to seven storeys high, some overhung the river by seven feet, and some overhung the road, to form a dark tunnel through which all traffic had to pass; this did not prevent the addition, in 1577, of the palatial Nonsuch House to the buildings that crowded the bridge. The available roadway was just 12 feet (4 m) wide, divided into two lanes, so that in each direction, carts, wagons, coaches and pedestrians shared a single file lane six feet wide. When the bridge was congested, crossing it could take up to an hour. Those who could afford the fare might prefer to cross by ferry, but the bridge structure had several undesirable effects on river traffic. The narrow arches and wide pier bases restricted the river's tidal ebb and flow, so that in hard winters, the river upstream of the bridge became more susceptible to freezing and impassable by boat. The flow was further obstructed in the 16th century by waterwheels (designed by Peter Morice) installed under the two north arches to drive water pumps, and under the two south arches to power grain mills; the difference in water levels on the two sides of the bridge could be as much as 6 feet (2 m), producing ferocious rapids between the piers resembling a weir.[14] Only the brave or foolhardy attempted to "shoot the bridge"—steer a boat between the starlings when in flood—and some were drowned in the attempt. The bridge was "for wise men to pass over, and for fools to pass under."[15]

The southern gatehouse became the scene of one of London's most notorious sights — a display of the severed heads of traitors, impaled on pikes[16] and dipped in tar and boiled to preserve them against the elements. The head of William Wallace was the first to appear on the gate, in 1305, starting a tradition that was to continue for another 355 years. Other famous heads on pikes included those of Jack Cade in 1450, Thomas More in 1535, Bishop John Fisher in the same year, and Thomas Cromwell in 1540. In 1598, a German visitor to London, Paul Hentzner, counted over 30 heads on the bridge:[17]

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

On the south is a bridge of stone eight hundred feet in length, of wonderful work; it is supported upon twenty piers of square stone, sixty feet high and thirty broad, joined by arches of about twenty feet diameter. The whole is covered on each side with houses so disposed as to have the appearance of a continued street, not at all of a bridge. Upon this is built a tower, on whose top the heads of such as have been executed for high treason are placed on iron spikes: we counted above thirty.

Evelyn's Diary noted that the practice stopped in 1660, following the Restoration of King Charles II,[18] but heads were reported at the site as late as 1772.[19] In 1666, the Great Fire of London first destroyed the bridge's waterwheels, preventing them from pumping water to fight the fire, and then burned one third of the houses on the bridge; a gap in the building left by a previous fire in 1633 prevented the destruction of the rest.[20]

London Bridge in 1757 just before the renovation, by Samuel Scott.

By 1710, most of the houses on the bridge had been rebuilt in the Restoration style and in order to widen the roadway to 20 feet (6 metres), the new houses were built overhanging the river supported by wooden girders and struts which hid the tops of the arches.[21] In 1722 congestion was becoming so serious that the Lord Mayor decreed that "all carts, coaches and other carriages coming out of Southwark into this City do keep all along the west side of the said bridge: and all carts and coaches going out of the City do keep along the east side of the said bridge." This has been suggested as one possible origin for the practice of traffic in Britain driving on the left.[22]

The last houses to be built on the bridge were designed by George Dance the Elder in 1745,[23] but even these elegant buildings had begun to subside within a decade.[24] In 1756, the London Bridge Act gave the City Corporation the power to purchase all the properties on the bridge so that they could be demolished and the bridge improved. While this work was underway, a temporary wooden bridge was constructed to the west of London Bridge. It opened in October 1757 but caught fire and collapsed in the following April. The old bridge was reopened until a new wooden construction could be completed a year later.[25] To help improve navigation under the bridge, its two centre arches were replaced by a single wider span, the Great Arch, in 1759. The last tenant on the bridge left in 1762 when the final buildings were cleared.[26] Under the supervision of Dance the Elder, the roadway was widened to 46 feet (14 metres)[27] and a balustrade was added "in the Gothic taste" together with fourteen stone alcoves for pedestrians to shelter in.[28] However, the creation of the Great Arch had weakened the rest of the structure and constant expensive repairs were required in the following decades; this, combined with congestion both on and under bridge, often leading to fatal accidents, resulted in public pressure for a modern replacement.[29]

London Bridge from Pepper Alley Stairs by Herbert Pugh, showing the appearance of London Bridge after 1762, with the new "Great Arch" at the centre.

Old London Bridge by J. M. W. Turner, showing the new balustrade and the back of one of the pedestrian alcoves.

One of the pedestrian alcoves from the 1762 renovation, now in Victoria Park, Tower Hamlets. A similar alcove from the same source can be seen at the Guy's Campus of King's College London.

A section of balustrade from London Bridge, now at Gilwell Park in Essex.

A relief of the Hanoverian Royal Arms from a gateway over the old London Bridge now forms part of the façade of the King's Arms pub, Southwark.

"New" London Bridge (1831–1967)

The Demolition of Old London Bridge, 1832, Guildhall Gallery, London.

New London Bridge in the late 19th century.

In 1799, a competition was opened to design a replacement for the medieval bridge. Entrants included Thomas Telford; he proposed a single iron arch span of 600 feet (180 m), with 65 feet (20 m) centre clearance beneath it for masted river traffic. His design was accepted as safe and practicable, following expert testimony.[30] Preliminary surveys and works were begun, but Telford's design required exceptionally wide approaches and the extensive use of multiple, steeply inclined planes, which would have required the purchase and demolition of valuable adjacent properties.[31] A more conventional design of five stone arches, by John Rennie, was chosen instead. It was built 100 feet (30 m) west (upstream) of the original site by Jolliffe and Banks of Merstham, Surrey,[32] under the supervision of Rennie's son. Work began in 1824 and the foundation stone was laid, in the southern coffer dam, on 15 June 1825.[citation needed]

Spare corbels for London bridge left behind at Swelltor Quarry on Dartmoor, Devon. They lie beside the former narrow gauge Plymouth and Dartmoor Railway.

The old bridge continued in use while the new bridge was being built, and was demolished after the latter opened in 1831. New approach roads had to be built, which cost three times as much as the bridge itself. The total costs, around £2.5 million (£223 million in 2018),[33] were shared by the British Government and the Corporation of London.

Rennie's bridge was 928 feet (283 m) long and 49 feet (15 m) wide, constructed from Haytor granite. The official opening took place on 1 August 1831; King William IV and Queen Adelaide attended a banquet in a pavilion erected on the bridge.

In 1896 the bridge was the busiest point in London, and one of its most congested; 8,000 pedestrians and 900 vehicles crossed every hour.[16] It was widened by 13 feet (4.0 m), using granite corbels.[34] Subsequent surveys showed that the bridge was sinking an inch (about 2.5 cm) every eight years, and by 1924 the east side had sunk some three to four inches (about 9 cm) lower than the west side. The bridge would have to be removed and replaced.

Sale to Robert McCulloch

Rennie's "New" London Bridge during its reconstruction at Lake Havasu City, Arizona, March 1971.

Rennie's "New" London Bridge rebuilt, Lake Havasu City, 2003.

In 1967, the Common Council of the City of London placed the bridge on the market and began to look for potential buyers. Council member Ivan Luckin had put forward the idea of selling the bridge, and recalled: "They all thought I was completely crazy when I suggested we should sell London Bridge when it needed replacing." On 18 April 1968, Rennie's bridge was purchased by the Missourian entrepreneur Robert P. McCulloch of McCulloch Oil for US$2,460,000. The claim that McCulloch believed mistakenly that he was buying the more impressive Tower Bridge was denied by Luckin in a newspaper interview.[35] As the bridge was taken apart, each piece was meticulously numbered. The blocks were then shipped via the Panama Canal to California and trucked from Long Beach to Arizona. The bridge was reconstructed by Sundt Construction at Lake Havasu City, Arizona, and re-dedicated on 10 October 1971. The reconstruction of Rennie's London Bridge spans the Bridgewater Channel canal that leads from the Uptown area of Lake Havasu City and follows McCulloch Boulevard onto an island that has yet to be named.

The London Bridge that was rebuilt at Lake Havasu City consists of a frame with stones from Rennie's London Bridge used as cladding. The cladding stones used are 150 to 200 millimetres (6 to 8 inches) thick. Some of the stones from the bridge were left behind at Merrivale Quarry at Princetown in Devon.[36] When Merrivale Quarry was abandoned and flooded in 2003, some of the remaining stones were sold in an online auction.[37]

Modern London Bridge

The current London Bridge was designed by architect Lord Holford and engineers Mott, Hay and Anderson.[38] It was constructed by contractors John Mowlem and Co from 1967 to 1972,[38] and opened by Queen Elizabeth II on 17 March 1973.[39] It comprises three spans of prestressed-concrete box girders, a total of 928 feet (283 m) long. The cost of £4 million (£55.5 million in 2018),[33] was met entirely by the Bridge House Estates charity. The current bridge was built in the same location as Rennie's bridge, with the previous bridge remaining in use while the first two girders were constructed upstream and downstream. Traffic was then transferred onto the two new girders, and the previous bridge demolished to allow the final two central girders to be added.[40]

The current London Bridge, pictured in January 1987. The skyscraper in the background is the National Westminster Tower (Tower 42), opened six years earlier.

In 1984, the British warship HMS Jupiter collided with London Bridge, causing significant damage to both the ship and the bridge.

On Remembrance Day 2004, several bridges in London were furnished with red lighting as part of a night-time flight along the river by wartime aircraft. London Bridge was the one bridge not subsequently stripped of the illuminations, which are regularly switched on at night.

The current London Bridge is often shown in films, news and documentaries showing the throng of commuters journeying to work into the City from London Bridge Station (south to north). An example of this is actor Hugh Grant crossing the bridge north to south during the morning rush hour, in the 2002 film About a Boy.

On 11 July 2009, as part of the annual Lord Mayor's charity Appeal and to mark the 800th anniversary of Old London Bridge's completion in the reign of King John, the Lord Mayor and Freemen of the City drove a flock of sheep across the bridge, supposedly by ancient right.[41]

London Bridge facing South towards The Shard

London Bridge with new barriers installed in 2017

On 3 June 2017, London Bridge was the target of a terrorist attack. Three Islamist terrorists used a rented van to ram pedestrians walking across the bridge, killing three. The attackers then drove their vehicle to nearby Borough Market, where they stabbed multiple people, five of whom died. Armed police arrived on scene and shot the three suspects dead. In addition to the eight innocent people killed in the attack, 48 were injured.[42] As a response, security barriers were installed between the bridge's pavement and road.[43]

Transport

The nearest London Underground stations are Monument, at the northern end of the bridge, and London Bridge at the southern end. London Bridge station is also served by National Rail.

London Bridge in literature and popular culture

- The nursery rhyme "London Bridge Is Falling Down" has been speculatively connected to several of the bridge's historic collapses.

- Rennie's Old London Bridge is a prominent landmark in T.S. Eliot's masterpiece "The Waste Land", wherein he compares the shuffling commuters across London Bridge to the hell-bound souls of Dante's Limbo.

Gary P. Nunn's song "London Homesick Blues" includes the lyrics, "Even London Bridge has fallen down, and moved to Arizona, now I know why." [44]

- London Bridge is named in the World War II song "The King is Still in London" by Roma Campbell-Hunter & Hugh Charles.[45]

See also

- Bridge (ward)

- List of Roman bridges

- Roman bridge

- List of crossings of the River Thames

- List of bridges in London

Notes

^ "Statutory Instrument 2000 No. 1117 – The GLA Roads Designation Order 2000". Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 2 May 2011..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

[permanent dead link]

^ "About us". TeamLondonBridge. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

^ Merrifield, Ralph, London, City of the Romans, University of California Press, 1983, pp. 1 – 4. The terraces were formed by glacial sediment towards the end of the last Ice Age.

^ D. Riley, in Burland, J.B., Standing, J.R., Jardine, F.M., Building Response to Tunnelling: Case Studies from Construction of the Jubilee line Extension, London, Volume 1, Thomas Telford, 2001, pp. 103 – 104.

^ The site of the new bridge determined the location of London itself. The alignment of Watling Street with the ford at Westminster (crossed via Thorney Island) is basis for a mooted earlier Roman "London", sited in the vicinity of Park Lane. See Margary, Ivan D., Roman Roads in Britain, Vol. 1, South of the Foss Way – Bristol Channel, Phoenix House Lts, London, 1955, pp. 46 – 47.

^ Margary, Ivan D., Roman Roads in Britain, Vol. 1, South of the Foss Way – Bristol Channel, Phoenix House Lts, London, 1955, pp. 46 – 48.

^ Jones, B., and Mattingly, D., An Atlas of Roman Britain, Blackwell, 1990, pp.168 – 172.

^ Merrifield, Ralph, London, City of the Romans, University of California Press, 1983, p. 31.

^ Jeremy Haslam, 'The Development of London of London by King Alfred: A Reassessment'; Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, 61 (2010), 109–44. Retrieved 2 August 2014

^ Snorri Sturluson (c. 1230), Heimskringla. There is no reference to this event in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. See: Hagland, Jan Ragnar; Watson, Bruce (Spring 2005). "Fact or folklore: the Viking attack on London Bridge" (PDF). London Archaeologist. 12: 328–33.

^ "Tornado extremes". Tornado and Storm Research Organisation. Archived from the original on 14 August 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

^ abc Thornbury, Walter, Old and New London, 1872, vol.2, p.10

^ Sabine, Ernest L., "Latrines and Cesspools of Mediaeval London," Speculum, Vol. 9, No. 3 (Jul. 1934), pp. 305–306, 315. Earliest evidence for the multi-seated public latrine is from a court case of 1306.

^ Pierce, p.45 and Jackson, p.77

^ Rev. John Ray, "Book of Proverbs", 1670, cited in Jackson, p.77

^ ab Dunton, Larkin (1896). The World and Its People. Silver, Burdett. p. 23.

^ "Vision of Britain - Paul Hentzner - Arrival and London". www.visionofbritain.org.uk.

^ Evelyn, John. Evelyn's Diary. Entry: 10 April 1696

^ Timbs, John. Curiosities of London. p.705, 1885. Available: books.google.com. Accessed: 29 September 2013

^ Pierce 2001, p. 206

^ Pierce 2001, p. 216

^ Ways of the World: A History of the World's Roads and of the Vehicles That Used Them, M. G. Lay & James E. Vance, Rutgers University Press 1992, p. 199.

^ Pierce 2001, pp. 235-6

^ Pierce 2001, p. 252

^ Pierce 2001, p. 252-256

^ Pierce 2001, p. 258-259

^ Pierce 2001, p. 260

^ Pierce 2001, pp. 261-263

^ Pierce 2001, p. 278-279

^ "Article on Iron Bridges". Encyclopedia Britannica. 1857.

^ Smiles, Samuel. The Life of Thomas Telford. ISBN 1404314857.

^ A fragment from the old bridge is set into the tower arch inside St Katharine's Church, Merstham.

^ ab UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

^ A dozen granite corbels prepared for this widening went unused, and still lie near Swelltor Quarry on the disused railway track a couple of miles south of Princetown on Dartmoor.

^ How London Bridge Was Sold To The States (from This Is Local London)

^ "London Bridge is still here! – 21/12/1995 – Contract Journal". Archived from the original on 6 May 2008.

^ "Merrivale Quarry, Whitchurch, Tavistock District, Devon, England, UK". www.mindat.org.

^ ab "Carillion accepts award for London Bridge project". Building talk. 14 November 2007. Archived from the original on 20 April 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

^ "Where Thames Smooth Waters Glide".

^ Yee, plate 65 and others

^ The Lord Mayor's Appeal

^ "'Van hits pedestrians' on London Bridge in 'major incident'". BBC. 3 June 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

^ Forster, Katie (5 June 2017). "London terror attack: Security barriers installed on three bridges in capital". The Independent. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

^ "London Homesick Blues". International Lyrics Playground. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

^ Huntley, Bill. "The King is Still in London". International Lyrics Playground. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

References

- Jackson, Peter, London Bridge – A Visual History, Historical Publications, revised edition, 2002,

ISBN 0-948667-82-6. - Murray, Peter & Stevens, Mary Anne, Living Bridges – The inhabited bridge, past, present and future, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1996,

ISBN 3-7913-1734-2. - Pierce, Patricia, Old London Bridge – The Story of the Longest Inhabited Bridge in Europe, Headline Books, 2001,

ISBN 0-7472-3493-0. - Watson, Bruce, Brigham, Trevor and Dyson, Tony, London Bridge: 2000 years of a river crossing, Museum of London Archaeology Service,

ISBN 1-901992-18-7. - Yee, Albert, London Bridge – Progress Drawings, no publisher, 1974,

ISBN 978-0-904742-04-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to London Bridge. |

- The London Bridge Museum and Educational Trust

Views of Old London Bridge ca. 1440, BBC London

- Southwark Council page with more info about the bridge

- Virtual reality tour of Old London Bridge

- Old London Bridge, Mechanics Magazine No. 318, September 1829

- The London Bridge Experience

The bridge that crossed an ocean (And the man who moved it) BBC News, 23 September 2018

Comments

Post a Comment