Hikone screen

A group plays a sugoroku board game in a detail of the Hikone screen

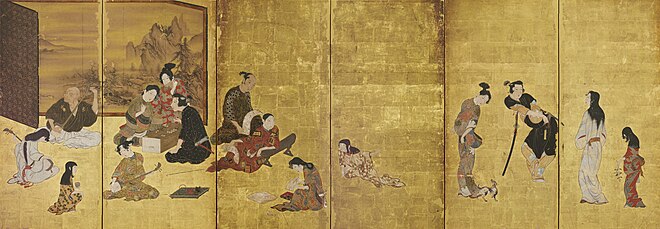

The Hikone screen (彦根屏風, Hikone byōbu) is a Japanese painted byōbu folding screen of unknown authorship made during the Kan'ei era (c. 1624–44). The 94-×-274.8-centimetre (37.0 × 108.2 in) screen folds in six parts and is painted on gold-leaf paper. It depicts people in the pleasure quarters of Kyoto playing music and games. The screen comes from the feudal Hikone Domain, ruled by the screen's owners, the Ii clan. It is owned by the city of Hikone in Shiga Prefecture, in the Ii Naochika Collection.

The work is seen as representative of early modern Japanese genre painting; some consider it the earliest work of ukiyo-e. In 1955 it was designated a National Treasure of Japan and given the official name Shihon Kinjichaku-shoku Fuzoku-zu (紙本金地著色風俗図).

Contents

1 Description

2 Analysis

3 Attribution

4 Provenance

5 Reception and legacy

6 Notes

7 References

7.1 Works cited

8 Further reading

9 External links

Description

The 94-×-274.8-centimetre (37.0 × 108.2 in) byōbu screen[1] depicts a scene in which eleven male and female figures amuse themselves. On the left, a blind man and some women play shamisens before a four-panel byōbu screen with a landscape painted on it. To their right a group of men and women play a sugoroku board game.[2]

The Hikone screen

Analysis

The manner of brushstrokes indicate the anonymous painting is in the style of the Kyō Kanō school. The activities of the figures in the Hikone screen display the traditional Four Arts of the Chinese Scholar. The clothing and personal items of the figures suggest the four seasons, as in traditional "four seasons pictures" (四季絵, shiki-e).[2]

Attribution

The work is anonymous, which would have been typical of such genre works; further, if the artist were of the Kanō or similar schools, the common subject matter would have been considered beneath the artist's dignity and thus would likely not have been signed. The screen was probably a commission, and it was customary for artists not to sign works made for those of high rank.[1]

At times the work was attributed to the painter Iwasa Matabei (1578–1650);[3] Until 1898 it was not known that Matabei had signed his paintings with the name Katsumochi, thus comparison with his actual works was not possible, and many anonymous works such as the Hikone screen were attributed to him.[4] His nickname was "Ukiyo Matabei", which was assumed to link him to the ukiyo demimonde and the ukiyo-e genre of art.[5] Works such as the Ukiyo-e Ruikō implied Matabei was the founder of the ukiyo-e,[3] and early Western scholars including Ernest Fenollosa also considered the screen a work of Matabei and an early work of ukiyo-e.[6] This attribution came to an end in 1898 with the discovery of Matabei's art name and the fact that the meaning of the word ukiyo bore different meanings before Asai Ryōi's use of it in 1661 to refer to the demimonde.[5] Paintings now known to be Matabei's are in the elegant, aristocratic Yamato-e tradition and show little of the liveliness and rich colouring associated with ukiyo-e.[7] His general association with the work nevertheless continued for generations.[8]

Provenance

As with almost all byōbu screens of the early modern period, no record remains of who commissioned the Hione screen, nor of who executed it. It is thought most likely the commission came from someone of the upper ranks of society, from the kuge aristocracy, a buke samurai house, or a machishū business leader.[9]

Ukiyo-e artist Hanegawa Chinchō (c. 1679–1754) depicted a man leaning against a panel of the Hikone screen; the caption states the screen was on display in the Shitaya neighbourhood of Edo in about 1745.[a] A record made states the painter Shibata Zeshin (1807–91) discovered the screen in the collection of an old Edo family, and later made a copy or derivative of it. The discovery is conjectured to have been c. 1833–36, and Zeshin's derivative c. 1840.[9]

Ii Naosuke (1815–60) may have first obtained the Hikone screen for the Ii clan of Hikone, of which he was the thirteenth family head.

The screen came into the collection of the Ii clan of the city of Hikone—its modern namesake—in what is now Shiga Prefecture no earlier than the late Edo period (1853–67). There is no record of the screen having been at the Ii residence in Edo,[b][9] though as it neither appears in the family records in Hikone it is presumed it remained in the capital until the Shōwa period.[10]

Tea master Takahashi Yoshio (1861–1937) recorded a Noh event at the Ii residence on 30 June 1912 at which Ii Naotada (1881–1947, fifteenth head of the family) had numerous art objects on display, including the Hikone screen; an unnamed member of the family told him "the famous ukiyo Matabei's Hikone screen" had first been obtained by Ii Naosuke (1815–60, thirteenth head of the family), who interested himself in curios and objets d'art.[10]

Reception and legacy

The Hikone screen resides in the Hikone Castle Museum

The work has been considered a masterpiece of Japanese genre painting since at least the mid-17th century. It has been widely copied, sometimes with variations, and some of the copies themselves have found renown.[1] In 1955 it was designated a National Treasure of Japan and given the official name Shihon Kinjichaku-shoku Fuzoku-zu (紙本金地著色風俗図).

Notes

^ The date given is Enkyō 2 (1 February 1745 – 22 January 1746).[9]

^ Under the sankin-kōtai system during the Edo period the Ii family would have been required to maintain a residence in Edo.

References

^ abc Kondo 1961, p. 144.

^ ab Kikuchi 1963, p. 106.

^ ab Kita 1999, pp. 44–45.

^ Kita 1999, p. 47.

^ ab Kita 1999, p. 50.

^ Kita 1999, pp. 44–45, 51.

^ Kita 1999, p. 48.

^ Kita 1999, p. 51.

^ abcd Takagi 2008, p. 104.

^ ab Takagi 2008, p. 105.

Works cited

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Kikuchi, Sadao (1963). Ukiyo-e. Hoikusha. ISBN 978-4-586-50021-5..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Kondo, Ichitaro (1961). Japanese Genre Painting: The Lively Art of Renaissance Japan,. translated by Roy Andrew Miller. Tuttle Publishing – via Questia. (Subscription required (help)).

Kita, Sandy (1999). The Last Tosa: Iwasa Katsumochi Matabei, Bridge to Ukiyo-e. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1826-5.

Takagi, Fumie (2008). "彦根屏風ー伝来と研究史". In Hikone Castle Museum; Tokyo Research Institute for Cultural Properties. Kokuhō Hikone byōbu jp:国宝彦根屛風 [Hikone Screen: A Japanese National Treasure]. Chuokoron-Shinsha. pp. 101–120. ISBN 978-4-8055-0557-1.

Further reading

Shirono, Seiji (2008). "光学的手法による国宝・彦根屏風の調査". In Hikone Castle Museum; Tokyo Research Institute for Cultural Properties. Kokuhō Hikone byōbu jp:国宝彦根屛風 [Hikone Screen: A Japanese National Treasure]. Chuokoron-Shinsha. pp. 121–124. ISBN 978-4-8055-0557-1.

Hayakawa, Yasuhiro (2008). "彦根屏風の色彩材料調査". In Hikone Castle Museum; Tokyo Research Institute for Cultural Properties. Kokuhō Hikone byōbu jp:国宝彦根屛風 [Hikone Screen: A Japanese National Treasure]. Chuokoron-Shinsha. pp. 125–144. ISBN 978-4-8055-0557-1.

Emura, Tomoko (2008). "彦根屏風の表現について". In Hikone Castle Museum; Tokyo Research Institute for Cultural Properties. Kokuhō Hikone byōbu jp:国宝彦根屛風 [Hikone Screen: A Japanese National Treasure]. Chuokoron-Shinsha. pp. 145–160. ISBN 978-4-8055-0557-1.

Takegami, Yukihiro (2008). "彦根屏風修理報告". In Hikone Castle Museum; Tokyo Research Institute for Cultural Properties. Kokuhō Hikone byōbu jp:国宝彦根屛風 [Hikone Screen: A Japanese National Treasure]. Chuokoron-Shinsha. pp. 161–170. ISBN 978-4-8055-0557-1.

External links

Details at the National Treasures of Japan website (in Japanese)

Comments

Post a Comment