Law of sines

A triangle labelled with the components of the law of sines. Capital A, B and C are the angles, and lower-case a, b, c are the sides opposite them. (a opposite A, etc.)

| Trigonometry |

|---|

|

|

Reference |

|

Laws and theorems |

|

Calculus |

|

In trigonometry, the law of sines, sine law, sine formula, or sine rule is an equation relating the lengths of the sides of a triangle (any shape) to the sines of its angles. According to the law,

- asinA=bsinB=csinC=d,{displaystyle {frac {a}{sin A}},=,{frac {b}{sin B}},=,{frac {c}{sin C}},=,d,}

where a, b, and c are the lengths of the sides of a triangle, and A, B, and C are the opposite angles (see the figure to the right), while d is the diameter of the triangle's circumcircle. When the last part of the equation is not used, the law is sometimes stated using the reciprocals;

- sinAa=sinBb=sinCc.{displaystyle {frac {sin A}{a}},=,{frac {sin B}{b}},=,{frac {sin C}{c}}.}

The law of sines can be used to compute the remaining sides of a triangle when two angles and a side are known—a technique known as triangulation. It can also be used when two sides and one of the non-enclosed angles are known. In some such cases, the triangle is not uniquely determined by this data (called the ambiguous case) and the technique gives two possible values for the enclosed angle.

The law of sines is one of two trigonometric equations commonly applied to find lengths and angles in scalene triangles, with the other being the law of cosines.

The law of sines can be generalized to higher dimensions on surfaces with constant curvature.[1]

Contents

1 Proof

2 The ambiguous case of triangle solution

3 Examples

3.1 Example 1

3.2 Example 2

4 Relation to the circumcircle

4.1 Proof

4.2 Relationship to the area of the triangle

5 Curvature

5.1 Spherical case

5.2 Vector Proof

5.3 Geometric Proof

5.4 Hyperbolic case

5.5 Unified formulation

6 Higher dimensions

7 History

8 See also

9 References

10 External links

Proof

The area T of any triangle can be written as one half of its base times its height. Selecting one side of the triangle as the base, the height of the triangle relative to that base is computed as the length of another side times the sine of the angle between the chosen side and the base. Thus, depending on the selection of the base the area of the triangle can be written as any of:

- T=12b(csinA)=12c(asinB)=12a(bsinC).{displaystyle T={frac {1}{2}}b(csin A)={frac {1}{2}}c(asin B)={frac {1}{2}}a(bsin C),.}

Multiplying these by 2/abc gives

- 2Tabc=sinAa=sinBb=sinCc.{displaystyle {frac {2T}{abc}}={frac {sin A}{a}}={frac {sin B}{b}}={frac {sin C}{c}},.}

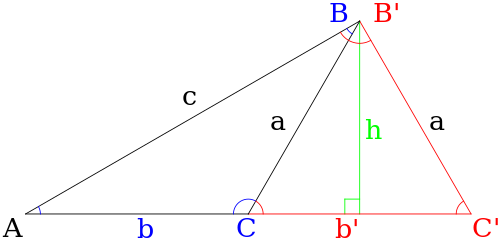

The ambiguous case of triangle solution

When using the law of sines to find a side of a triangle, an ambiguous case occurs when two separate triangles can be constructed from the data provided (i.e., there are two different possible solutions to the triangle). In the case shown below they are triangles ABC and AB′C′.

Given a general triangle, the following conditions would need to be fulfilled for the case to be ambiguous:

- The only information known about the triangle is the angle A and the sides a and c.

- The angle A is acute (i.e., A < 90°).

- The side a is shorter than the side c (i.e., a < c).

- The side a is longer than the altitude h from angle B, where h = c sin A (i.e., a > h).

If all the above conditions are true, then both angles C or C′ produce a valid triangle, meaning that both of the following are true:

- C′=arcsincsinAa or C=π−arcsincsinAa.{displaystyle C'=arcsin {frac {csin A}{a}}{text{ or }}C=pi -arcsin {frac {csin A}{a}}.}

From there we can find the corresponding B and b or B′ and b′ if required, where b is the side bounded by angles A and C and b′ bounded by A and C′.

Without further information it is impossible to decide which is the triangle being asked for.

Examples

The following are examples of how to solve a problem using the law of sines.

Example 1

Given: side a = 20, side c = 24, and angle C = 40°. Angle A is desired.

Using the law of sines, we conclude that

- sinA20=sin40∘24.{displaystyle {frac {sin A}{20}}={frac {sin 40^{circ }}{24}}.}

- A=arcsin(20sin40∘24)≈32.39∘.{displaystyle A=arcsin left({frac {20sin 40^{circ }}{24}}right)approx 32.39^{circ }.}

Note that the potential solution A = 147.61° is excluded because that would necessarily give A + B + C > 180°.

Example 2

If the lengths of two sides of the triangle a and b are equal to x, the third side has length c, and the angles opposite the sides of lengths a, b, and c are A, B, and C respectively then

- A=B=180∘−C2=90∘−C2sinA=sinB=sin(90∘−C2)=cos(C2)csinC=asinA=xcos(C2)ccos(C2)sinC=x{displaystyle {begin{aligned}&A=B={frac {180^{circ }-C}{2}}=90^{circ }-{frac {C}{2}}\[6pt]&sin A=sin B=sin left(90^{circ }-{frac {C}{2}}right)=cos left({frac {C}{2}}right)\[6pt]&{frac {c}{sin C}}={frac {a}{sin A}}={frac {x}{cos left({frac {C}{2}}right)}}\[6pt]&{frac {ccos left({frac {C}{2}}right)}{sin C}}=xend{aligned}}}

Relation to the circumcircle

In the identity

- asinA=bsinB=csinC,{displaystyle {frac {a}{sin A}}={frac {b}{sin B}}={frac {c}{sin C}},}

the common value of the three fractions is actually the diameter of the triangle's circumcircle which dates back to Ptolemy.[2][3]

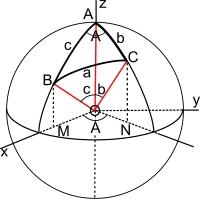

Deriving the ratio of the sine law equal to the circumscribing diameter. Note that triangle ADB passes through the center of the circumscribing circle.

Proof

As shown in the figure, let's have a circle with inscribed△ABC{displaystyle bigtriangleup ABC}

- sinD=oppositehypotenuse=c2R{displaystyle sin D={frac {text{opposite}}{text{hypotenuse}}}={frac {c}{2R}}}

Angles ∠C{displaystyle angle C}

- sinD=sinC=c2R{displaystyle sin D=sin C={frac {c}{2R}}}

Rearranging,

- 2R=csinC{displaystyle 2R={frac {c}{sin C}}}

Repeating the process of creating △ADB{displaystyle bigtriangleup ADB}

asinA=bsinB=csinC=2R{displaystyle {frac {a}{sin A}}={frac {b}{sin B}}={frac {c}{sin C}}=2R}

where R{displaystyle R}

Relationship to the area of the triangle

The area of a triangle can be solved by T=0.5absinθ{displaystyle T=0.5absin theta }

- T=12ab⋅c2R{displaystyle T={frac {1}{2}}abcdot {frac {c}{2R}}}

Taking R{displaystyle R}

T=abc4R{displaystyle T={frac {abc}{4R}}}

It can also be shown that this quantity is equal to

- abc2T=abc2s(s−a)(s−b)(s−c)=2abc(a2+b2+c2)2−2(a4+b4+c4),{displaystyle {begin{aligned}{frac {abc}{2T}}&={frac {abc}{2{sqrt {s(s-a)(s-b)(s-c)}}}}\[6pt]&={frac {2abc}{sqrt {{(a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2})}^{2}-2(a^{4}+b^{4}+c^{4})}}},end{aligned}}}

where T is the area of the triangle and s is the semiperimeter

- s=a+b+c2.{displaystyle s={frac {a+b+c}{2}}.}

The second equality above readily simplifies to Heron's formula for the area. Neatly, it can be written as

- R=abc4T{displaystyle R={frac {abc}{4T}}}

where R is the radius of the triangle's circumcircle.

Curvature

The law of sines takes on a similar form in the presence of curvature.

Spherical case

In the spherical case, the formula is:

- sinAsinα=sinBsinβ=sinCsinγ.{displaystyle {frac {sin A}{sin alpha }}={frac {sin B}{sin beta }}={frac {sin C}{sin gamma }}.}

Here, α, β, and γ are the angles at the center of the sphere subtended by the three arcs of the spherical surface triangle a, b, and c, respectively. A, B, and C are the surface angles opposite their respective arcs.

Vector Proof

Consider a unit sphere with three unit vectors OA, OB and OC drawn from the origin to the vertices of the triangle. Thus the angles α, β, and γ are the angles a, b, and c, respectively. The arc BC subtends an angle of magnitude a at the centre. Introduce a Cartesian basis with OA along the z-axis and OB in the xz-plane making an angle c with the z-axis. The vector OC projects to ON in the xy-plane and the angle between ON and the x-axis is A. Therefore, the three vectors have components:

- OA=(001),OB=(sinc0cosc),OC=(sinbcosAsinbsinAcosb).{displaystyle mathbf {OA} ={begin{pmatrix}0\0\1end{pmatrix}},quad mathbf {OB} ={begin{pmatrix}sin c\0\cos cend{pmatrix}},quad mathbf {OC} ={begin{pmatrix}sin bcos A\sin bsin A\cos bend{pmatrix}}.}

The scalar triple product, OA · (OB × OC) is the volume of the parallelepiped formed by the position vectors of the vertices of the spherical triangle OA, OB and OC. This volume is invariant to the specific coordinate system used to represent OA, OB and OC. The value of the scalar triple product OA · (OB × OC) is the 3 × 3 determinant with OA, OB and OC as its rows. With the z-axis along OA the square of this determinant is

- (OA⋅(OB×OC))2=(det(OA,OB,OC))2=(|001sinc0coscsinbcosAsinbsinAcosb|)2=(sinbsincsinA)2.{displaystyle {begin{aligned}{bigl (}mathbf {OA} cdot (mathbf {OB} times mathbf {OC} ){bigr )}^{2}&={bigl (}det(mathbf {OA} ,mathbf {OB} ,mathbf {OC} ){bigr )}^{2}\[4pt]&=left({begin{vmatrix}0&0&1\sin c&0&cos c\sin bcos A&sin bsin A&cos bend{vmatrix}}right)^{2}=left(sin bsin csin Aright)^{2}.end{aligned}}}

Repeating this calculation with the z-axis along OB gives (sin c sin a sin B)2, while with the z-axis along OC it is (sin a sin b sin C)2. Equating these expressions and dividing throughout by (sin a sin b sin c)2 gives

- sin2Asin2a=sin2Bsin2b=sin2Csin2c=V2sin2asin2bsin2c,{displaystyle {frac {sin ^{2}A}{sin ^{2}a}}={frac {sin ^{2}B}{sin ^{2}b}}={frac {sin ^{2}C}{sin ^{2}c}}={frac {V^{2}}{sin ^{2}asin ^{2}bsin ^{2}c}},}

where V is the volume of the parallelepiped formed by the position vector of the vertices of the spherical triangle.

It is easy to see how for small spherical triangles, when the radius of the sphere is much greater than the sides of the triangle, this formula becomes the planar formula at the limit, since

- limα→0sinαα=1{displaystyle lim _{alpha rightarrow 0}{frac {sin alpha }{alpha }}=1}

and the same for sin β and sin γ.

Geometric Proof

Consider a unit circle with:

OA=OB=OC=1{displaystyle OA=OB=OC=1}

Construct point D{displaystyle D}

Construct point A′{displaystyle A'}

It can therefore be seen that ∠ADA′=B{displaystyle angle ADA'=B}

Notice that A′{displaystyle A'}

By basic trigonometry, we have:

AD=sinc{displaystyle AD=sin c}

AE=sinb{displaystyle AE=sin b}

But AA′=ADsinB=AEsinC{displaystyle AA'=ADsin B=AEsin C}

Combining them we have:

sincsinB=sinbsinC{displaystyle sin csin B=sin bsin C}

sinBsinb=sinCsinc{displaystyle {frac {sin B}{sin b}}={frac {sin C}{sin c}}}

By applying similar reasoning, we obtain the spherical law of sine:

sinAsina=sinBsinb=sinCsinc{displaystyle {frac {sin A}{sin a}}={frac {sin B}{sin b}}={frac {sin C}{sin c}}}

Hyperbolic case

In hyperbolic geometry when the curvature is −1, the law of sines becomes

- sinAsinha=sinBsinhb=sinCsinhc.{displaystyle {frac {sin A}{sinh a}}={frac {sin B}{sinh b}}={frac {sin C}{sinh c}},.}

In the special case when B is a right angle, one gets

- sinC=sinhcsinhb{displaystyle sin C={frac {sinh c}{sinh b}}}

which is the analog of the formula in Euclidean geometry expressing the sine of an angle as the opposite side divided by the hypotenuse.

- See also hyperbolic triangle.

Unified formulation

Define a generalized sine function, depending also on a real parameter K:

- sinKx=x−Kx33!+K2x55!−K3x77!+⋯.{displaystyle sin _{K}x=x-{frac {Kx^{3}}{3!}}+{frac {K^{2}x^{5}}{5!}}-{frac {K^{3}x^{7}}{7!}}+cdots .}

The law of sines in constant curvature K reads as[1]

- sinAsinKa=sinBsinKb=sinCsinKc.{displaystyle {frac {sin A}{sin _{K}a}}={frac {sin B}{sin _{K}b}}={frac {sin C}{sin _{K}c}},.}

By substituting K = 0, K = 1, and K = −1, one obtains respectively the Euclidean, spherical, and hyperbolic cases of the law of sines described above.

Let pK(r) indicate the circumference of a circle of radius r in a space of constant curvature K. Then pK(r) = 2π sinKr. Therefore the law of sines can also be expressed as:

- sinApK(a)=sinBpK(b)=sinCpK(c).{displaystyle {frac {sin A}{p_{K}(a)}}={frac {sin B}{p_{K}(b)}}={frac {sin C}{p_{K}(c)}},.}

This formulation was discovered by János Bolyai.[5]

Higher dimensions

For an n-dimensional simplex (i.e., triangle (n = 2), tetrahedron (n = 3), pentatope (n = 4), etc.) in n-dimensional Euclidean space, the absolute value of the polar sine of the normal vectors of the faces that meet at a vertex, divided by the hyperarea of the face opposite the vertex is independent of the choice of the vertex. Writing V for the hypervolume of the n-dimensional simplex and P for the product of the hyperareas of its (n−1)-dimensional faces, the common ratio is

- (nV)n−1(n−1)!P.{displaystyle {frac {(nV)^{n-1}}{(n-1)!P}}.}

For example, a tetrahedron has four triangular faces. The absolute value of the polar sine of the normal vectors to the three faces that share a vertex, divided by the area of the fourth face will not depend upon the choice of the vertex:

- |psin(n2,n3,n4)|Area1=|psin(n1,n3,n4)|Area2=|psin(n1,n2,n4)|Area3=|psin(n1,n2,n3)|Area4=(3Volumetetrahedron)22! Area1Area2Area3Area4.{displaystyle {begin{aligned}&{frac {{bigl |}operatorname {psin} (mathbf {n_{2}} ,mathbf {n_{3}} ,mathbf {n_{4}} ){bigr |}}{mathrm {Area} _{1}}}={frac {{bigl |}operatorname {psin} (mathbf {n_{1}} ,mathbf {n_{3}} ,mathbf {n_{4}} ){bigr |}}{mathrm {Area} _{2}}}={frac {{bigl |}operatorname {psin} (mathbf {n_{1}} ,mathbf {n_{2}} ,mathbf {n_{4}} ){bigr |}}{mathrm {Area} _{3}}}={frac {{bigl |}operatorname {psin} (mathbf {n_{1}} ,mathbf {n_{2}} ,mathbf {n_{3}} ){bigr |}}{mathrm {Area} _{4}}}\[4pt]={}&{frac {(3operatorname {Volume} _{mathrm {tetrahedron} })^{2}}{2!~mathrm {Area} _{1}mathrm {Area} _{2}mathrm {Area} _{3}mathrm {Area} _{4}}},.end{aligned}}}

History

According to Ubiratàn D'Ambrosio and Helaine Selin, the spherical law of sines was discovered in the 10th century. It is variously attributed to Abu-Mahmud Khojandi, Abu al-Wafa' Buzjani, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi and Abu Nasr Mansur.[6]

Ibn Muʿādh al-Jayyānī's The book of unknown arcs of a sphere in the 11th century contains the general law of sines.[7] The plane law of sines was later stated in the 13th century by Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī. In his On the Sector Figure, he stated the law of sines for plane and spherical triangles, and provided proofs for this law.[8]

According to Glen Van Brummelen, "The Law of Sines is really Regiomontanus's foundation for his solutions of right-angled triangles in Book IV, and these solutions are in turn the bases for his solutions of general triangles."[9] Regiomontanus was a 15th-century German mathematician.

See also

- Gersonides

Half-side formula – for solving spherical triangles

- Law of cosines

- Law of tangents

- Law of cotangents

Mollweide's formula – for checking solutions of triangles- Solution of triangles

- Surveying

References

^ ab "Generalized law of sines". mathworld..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Coxeter, H. S. M. and Greitzer, S. L. Geometry Revisited. Washington, DC: Math. Assoc. Amer., pp. 1–3, 1967

^ ab "Law of Sines". www.pballew.net. Retrieved 2018-09-18.

^ Mr. T's Math Videos (2015-06-10), Area of a Triangle and Radius of its Circumscribed Circle, retrieved 2018-09-18

^ Katok, Svetlana (1992). Fuchsian groups. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 22. ISBN 0-226-42583-5.

^ Sesiano just lists al-Wafa as a contributor. Sesiano, Jacques (2000) "Islamic mathematics" pp. 137–157, in Selin, Helaine; D'Ambrosio, Ubiratan (2000), Mathematics Across Cultures: The History of Non-western Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 1-4020-0260-2

^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Abu Abd Allah Muhammad ibn Muadh Al-Jayyani", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

^ Berggren, J. Lennart (2007). "Mathematics in Medieval Islam". The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook. Princeton University Press. p. 518. ISBN 978-0-691-11485-9.

^ Glen Van Brummelen (2009). "The mathematics of the heavens and the earth: the early history of trigonometry". Princeton University Press. p.259.

ISBN 0-691-12973-8

External links

Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001) [1994], "Sine theorem", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

The Law of Sines at cut-the-knot

- Degree of Curvature

- Finding the Sine of 1 Degree

- Generalized law of sines to higher dimensions

- Law of Sines - ProofWiki

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}&A=B={frac {180^{circ }-C}{2}}=90^{circ }-{frac {C}{2}}\[6pt]&sin A=sin B=sin left(90^{circ }-{frac {C}{2}}right)=cos left({frac {C}{2}}right)\[6pt]&{frac {c}{sin C}}={frac {a}{sin A}}={frac {x}{cos left({frac {C}{2}}right)}}\[6pt]&{frac {ccos left({frac {C}{2}}right)}{sin C}}=xend{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2328329b896839b2f5094298ee5291377b352f06)

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}{frac {abc}{2T}}&={frac {abc}{2{sqrt {s(s-a)(s-b)(s-c)}}}}\[6pt]&={frac {2abc}{sqrt {{(a^{2}+b^{2}+c^{2})}^{2}-2(a^{4}+b^{4}+c^{4})}}},end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b0791f9e5aaf7e592ffdd98ae27e4b34555d1a68)

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}{bigl (}mathbf {OA} cdot (mathbf {OB} times mathbf {OC} ){bigr )}^{2}&={bigl (}det(mathbf {OA} ,mathbf {OB} ,mathbf {OC} ){bigr )}^{2}\[4pt]&=left({begin{vmatrix}0&0&1\sin c&0&cos c\sin bcos A&sin bsin A&cos bend{vmatrix}}right)^{2}=left(sin bsin csin Aright)^{2}.end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b2d15bd24a2d8e3df9e3b7478c66840e397f1e40)

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}&{frac {{bigl |}operatorname {psin} (mathbf {n_{2}} ,mathbf {n_{3}} ,mathbf {n_{4}} ){bigr |}}{mathrm {Area} _{1}}}={frac {{bigl |}operatorname {psin} (mathbf {n_{1}} ,mathbf {n_{3}} ,mathbf {n_{4}} ){bigr |}}{mathrm {Area} _{2}}}={frac {{bigl |}operatorname {psin} (mathbf {n_{1}} ,mathbf {n_{2}} ,mathbf {n_{4}} ){bigr |}}{mathrm {Area} _{3}}}={frac {{bigl |}operatorname {psin} (mathbf {n_{1}} ,mathbf {n_{2}} ,mathbf {n_{3}} ){bigr |}}{mathrm {Area} _{4}}}\[4pt]={}&{frac {(3operatorname {Volume} _{mathrm {tetrahedron} })^{2}}{2!~mathrm {Area} _{1}mathrm {Area} _{2}mathrm {Area} _{3}mathrm {Area} _{4}}},.end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/673dfe8c9ced0f9be24b0a0751af902b91784adc)

Comments

Post a Comment