Method acting

Marlon Brando's performance in Elia Kazan's film of A Streetcar Named Desire exemplified the power of Stanislavski-based acting in cinema.[1]

Method acting is a range of training and rehearsal techniques that seek to encourage sincere and emotionally expressive performances, as formulated by a number of different theatre practitioners. These techniques are built on Stanislavski's system, developed by the Russian actor and director Konstantin Stanislavski and captured in his books An Actor Prepares, Building a Character, and Creating a Role.[2]

Among those who have contributed to the development of the Method, three teachers are associated with "having set the standard of its success", each emphasizing different aspects of the approach: Lee Strasberg (the psychological aspects), Stella Adler (the sociological aspects), and Sanford Meisner (the behavioral aspects).[3] The approach was first developed when they worked together at the Group Theatre in New York.[2] All three subsequently claimed to be the rightful heirs of Stanislavski's approach.

Contents

1 From the "system" to the Method

1.1 Russia

1.2 America

1.3 Canada

1.4 United Kingdom

1.5 Australia & New Zealand

1.6 Europe & Other Countries

2 Emotion and imagination

3 Modification of Strasberg's Techniques

3.1 America

3.2 Canada

3.3 United Kingdom

3.4 Australia & New Zealand

3.5 Europe & Other

4 Critical Reception of Stanislavski's Method

4.1 America

4.2 Canada

4.3 United Kingdom

4.4 Australia & New Zealand

4.5 Europe & Other

5 Indian cinema

6 Psychological effects

7 List of method actors

8 See also

9 Notes

10 Sources

10.1 Primary sources

10.2 Secondary sources

From the "system" to the Method

"The Method" is an elaboration of the "system" of acting developed by the Russian theatre practitioner Konstantin Stanislavski. In the first three decades of the 20th century, Stanislavski organized his training, preparation, and rehearsal techniques into a coherent, systematic methodology. The "system" brought together and built on: (1) the director-centred, unified aesthetic and disciplined, ensemble approach of the Meiningen company; (2) the actor-centred realism of the Maly; (3) and the Naturalistic staging of Antoine and the independent theatre movement.[4]

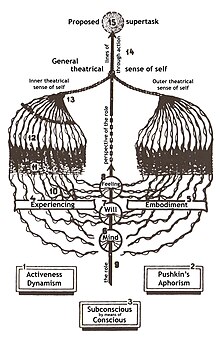

A diagram of Stanislavski's "system", based on his "Plan of Experiencing" (1935).

The "system" cultivates what Stanislavski calls the "art of experiencing" (to which he contrasts the "art of representation").[5] It mobilises the actor's conscious thought and will in order to activate other, less-controllable psychological processes—such as emotional experience and subconscious behaviour—sympathetically and indirectly.[6] In rehearsal, the actor searches for inner motives to justify action and the definition of what the character seeks to achieve at any given moment (a "task").[7] Later, Stanislavski further elaborated the "system" with a more physically grounded rehearsal process known as the "Method of Physical Action".[8] Minimising at-the-table discussions, he now encouraged an "active analysis", in which the sequence of dramatic situations are improvised.[9] "The best analysis of a play", Stanislavski argued, "is to take action in the given circumstances."[10]

As well as Stanislavski's early work, the ideas and techniques of Yevgeny Vakhtangov (a Czechoslovakian student who had died in 1922 at the age of 39) were also an important influence on the development of the Method. Vakhtangov's "object exercises" were developed further by Uta Hagen as a means for actor training and the maintenance of skills. Strasberg attributed to Vakhtangov the distinction between Stanislavski's process of "justifying" behaviour with the inner motive forces that prompt that behaviour in the character and "motivating" behaviour with imagined or recalled experiences relating to the actor and substituted for those relating to the character. Following this distinction, actors ask themselves "What would motivate me, the actor, to behave in the way the character does?" rather than the more Stanislavskian question "Given the particular circumstances of the play, how would I behave, what would I do, how would I feel, how would I react?"[11]

Russia

America

In America the transmission of the earliest phase of Stanislavski's work via the students of the First Studio of the Moscow Art Theatre (MAT) revolutionized acting in the West.[12] When the MAT toured the US in the early 1920s, Richard Boleslavsky, one of Stanislavski's students from the First Studio, presented a series of lectures on the "system" that were eventually published as Acting: The First Six Lessons (1933). The interest generated led to a decision by Boleslavsky and Maria Ouspenskaya (another student at the First Studio) to emigrate to the US and to establish the American Laboratory Theatre.[13]

However, the version of Stanislavski's practice these students took to the US with them was that developed in the 1910s, rather than the more fully elaborated version of the "system" detailed in Stanislavski's acting manuals from the 1930s, An Actor's Work and An Actor's Work on a Role. The first half of An Actor's Work, which treated the psychological elements of training, was published in a heavily abridged and misleadingly translated version in the US as An Actor Prepares in 1936. English-language readers often confused the first volume on psychological processes with the "system" as a whole.[14]

T

Many of the American practitioners who came to be identified with the Method were taught by Boleslavsky and Ouspenskaya at the American Laboratory Theatre.[15] The approaches to acting subsequently developed by their students—including Lee Strasberg, Stella Adler, and Sanford Meisner—are often confused with Stanislavski's "system".

Canada

United Kingdom

Australia & New Zealand

Europe & Other Countries

Emotion and imagination

Among the concepts and techniques of method acting are substitution, "as if", sense memory, affective memory, and animal work (all of which were first developed by Stanislavski). Contemporary method actors sometimes seek help from psychologists in the development of their roles.[16]

In Strasberg's approach, actors make use of experiences from their own lives to bring them closer to the experience of their characters. This technique, which Stanislavski came to call emotion memory (Strasberg tends to use the alternative formulation, "affective memory"), involves the recall of sensations involved in experiences that made a significant emotional impact on the actor. Without faking or forcing, actors allow those sensations to stimulate a response and try not to inhibit themselves.

Stanislavski's approach rejected emotion memory except as a last resort and prioritised physical action as an indirect pathway to emotional expression.[17] This can be seen in Stanislavki's notes for Leonidov in the production plan for Othello and in Benedetti's discussion of his training of actors at home and latervabroad.[17] Stanislavski confirmed this emphasis in his discussions with Harold Clurman in late 1935.[18]

In training, as distinct from rehearsal process, the recall of sensations to provoke emotional experience and the development of a vividly imagined fictional experience remained a central part both of Stanislavski's and the various Method-based approaches that developed out of it.

A widespread misconception about method acting—particularly in the popular media—equates method actors with actors who choose to remain in character even offstage or off-camera for the duration of a project.[citation needed] In his book A Dream of Passion, Strasberg wrote that Stanislavski, early in his directing career, "require[d] his actors to live 'in character' off stage", but that "the results were never fully satisfactory".[19] Stanislavski did experiment with this approach in his own acting before he became a professional actor and founded the Moscow Art Theatre, though he soon abandoned it.[20] Some method actors employ this technique, such as Daniel Day-Lewis, but Strasberg did not include it as part of his teachings and it "is not part of the Method approach".[21]

Strasberg's students included many prominent American actors of the latter half of the 20th century, including Paul Newman, Al Pacino, George Peppard, Dustin Hoffman, James Dean, Marilyn Monroe, Jane Fonda, Jack Nicholson, Mickey Rourke, among others.[22]

Modification of Strasberg's Techniques

America

Stella Adler, an actress and acting teacher whose students included Marlon Brando, Warren Beatty, and Robert De Niro, also broke with Strasberg after she studied with Stanislavski. Her version of the method is based on the idea that actors should stimulate emotional experience by imagining the scene's "given circumstances", rather than recalling experiences from their own lives. Adler's approach also seeks to stimulate the actor's imagination through the use of "as ifs", which substitute more personally affecting imagined situations for the circumstances experienced by the character.

Strasberg's Method & Critcism

The charge that Strasberg's method distorted Stanislavski's system has been responsible for a considerable revivalist interest in Stanislavski's "pure" teachings. As the use of the Method has declined considerably from its peak in the mid-20th century, acting teachers claiming to teach Stanislavski's unadulterated system are becoming more numerous.[citation needed]

Canada

United Kingdom

Australia & New Zealand

Europe & Other

Critical Reception of Stanislavski's Method

America

Alfred Hitchcock described his work with Montgomery Clift in I Confess as difficult "because you know, he was a method actor". He recalled similar problems with Paul Newman in Torn Curtain.[23]Lillian Gish quipped: "It's ridiculous. How would you portray death if you had to experience it first?"[24]Charles Laughton, who worked closely for a time with Bertolt Brecht, argued that "Method actors give you a photograph", while "real actors give you an oil painting."[25]

During the filming of Marathon Man (1976), Laurence Olivier, who had lost patience with method acting two decades earlier while filming The Prince and the Showgirl (1957), was said to have quipped to Dustin Hoffman, after Hoffman stayed up all night to match his character's situation, that Hoffman should "try acting... It's so much easier."[26]

The charge that Strasberg's method distorted Stanislavski's system has been responsible for a considerable revivalist interest in Stanislavski's "pure" teachings. As the use of the Method has declined considerably from its peak in the mid-20th century, acting teachers claiming to teach Stanislavski's unadulterated system are becoming more numerous.[citation needed]

Canada

United Kingdom

Australia & New Zealand

Europe & Other

Indian cinema

In Indian cinema, a form of method acting was developed independently from American cinema. Dilip Kumar, a Hindi cinema actor who debuted in the 1940s and eventually became one of the biggest Indian movie stars of the 1950s and 1960s, was a pioneer of method acting, predating Hollywood method actors such as Marlon Brando. Kumar inspired many future Indian actors, from Amitabh Bachchan and Naseeruddin Shah to Nawazuddin Siddiqui.[27][28] Kumar, who pioneered his own form of method acting without any acting school experience,[29] was described as "the ultimate method actor" (natural actor) by the famous filmmaker Satyajit Ray.[30],

Psychological effects

When the felt emotions of a played character are not compartmentalized, they can encroach on other facets of life, often seeming to disrupt the actor’s psyche. This occurs as the actor delves into previous emotional experiences, be they joyful or traumatic.[31] The psychological effects, like emotional fatigue, comes when suppressed or unresolved raw emotions are unburied to add to the character,[32] not just from the employing personal emotions in performance.

Fatigue, or emotional fatigue, comes mainly when actors “create dissonance between their actions and their actual feelings.”.[33] A mode of acting referred to as “surface acting” involves only changing one’s actions without altering the deeper thought processes. Method acting, when employed correctly, is mainly deep acting, or changing thoughts as well as actions, proven to generally avoid excessive fatigue. Surface acting is statistically “positively associated with a negative mood and this explains some of the association of surface acting with increased emotional exhaustion.” [34] This negative mood that is created leads to fear, anxiety, feelings of shame and sleep deprivation.

Raw emotion or unresolved emotions conjured up for acting, may result in a sleep deprivation and the cyclical nature of the ensuing side effects. Sleep deprivation alone can lead to impaired function, causing some individuals to “acute episodes of psychosis.” Sleep deprivation initiates chemical changes in the brain that can lead to behavior similar to psychotic individuals.[35] These episodes can lead to more lasting psychological damage. In cases where raw emotion that has not been resolved, or traumas have been evoked before closure has been reached by the individual, the emotion can result in greater emotional instability and increased sense of anxiety, fear or shame.[36]

List of method actors

Ann Bancroft

Christian Bale[37]

Warren Beatty[38]

Marlon Brando[39]

Adrien Brody[40]

Nicolas Cage[41]

Michael Caine[42]

Jim Carrey[43]

Montgomery Clift[44]

Daniel Day-Lewis[45]

James Dean[46]

Robert De Niro[47]

Johnny Depp[48]

Leonardo DiCaprio[49]

Michael Fassbender[50]

Sally Field[51]

James Franco[52]

Ed Harris[53]

Dustin Hoffman[54]

Angelina Jolie[55]

Val Kilmer[56]

Shia LaBeouf[57]

Heath Ledger[58]

Jared Leto[59]

Paul Newman[60]

Jack Nicholson[61]

Edward Norton[62]

Gary Oldman[63]

Al Pacino[64]

Sean Penn[65]

Joaquin Phoenix[66]

Sidney Poitier[67]

Peter Sellers[68]

Andy Serkis[69]

Hilary Swank[70]

Michelle Williams[71]

See also

- List of acting techniques

Notes

^ Blum (1984, 63) and Hayward (1996, 216).

^ ab Krasner (2000b, 130).

^ Krasner (2000b, 129).

^ Benedetti (1989, 5–11, 15, 18) and (1999b, 254), Braun (1982, 59), Carnicke (2000, 13, 16, 29), Counsell (1996, 24), Gordon (2006, 38, 40–41), and Innes (2000, 53–54).

^ Benedetti (1999a, 201), Carnicke (2000, 17), and Stanislavski (1938, 16–36). Stanislavski's "art of representation" corresponds to Mikhail Shchepkin's "actor of reason" and his "art of experiencing" corresponds to Shchepkin's "actor of feeling"; see Benedetti (1999a, 202).

^ Benedetti (1999a, 170).

^ Benedetti (1999a, 182–183).

^ Benedetti (1999a, 325, 360) and (2005, 121) and Roach (1985, 197–198, 205, 211–215). The term "Method of Physical Action" was applied to this rehearsal process after Stanislavski's death. Benedetti indicates that though Stanislavski had developed it since 1916, he first explored it practically in the early 1930s; see (1998, 104) and (1999a, 356, 358). Gordon argues the shift in working-method happened during the 1920s (2006, 49–55). Vasili Toporkov, an actor who trained under Stanislavski in this approach, provides in his Stanislavski in Rehearsal (2004) a detailed account of the Method of Physical Action at work in Stanislavski's rehearsals.

^ Benedetti (1999a, 355–256), Carnicke (2000, 32–33), Leach (2004, 29), Magarshack (1950, 373–375), and Whyman (2008, 242).

^ Quoted by Carnicke (1998, 156). Stanislavski continues: "For in the process of action the actor gradually obtains the mastery over the inner incentives of the actions of the character he is representing, evoking in himself the emotions and thoughts which resulted in those actions. In such a case, an actor not only understands his part, but also feels it, and that is the most important thing in creative work on the stage"; quoted by Magarshack (1950, 375).

^ Carnicke (2009, 221).

^ Carnicke (1998, 1, 167) and (2000, 14), Counsell (1996, 24–25), Golub (1998, 1032), Gordon (2006, 71–72), Leach (2004, 29), and Milling and Ley (2001, 1–2).

^ Benedetti (1999a, 283, 286) and Gordon (2006, 71–72).

^ Benedetti (1999a, 332).

^ Krasner (2000b, 129–130).

^ Kase (2011, 125) and Hull (1985, 10).

^ ab Benedetti (1999a, 351–352).

^ Benedetti (1999a, 351–352).

^ Strasberg (1988, 44).

^ Benedetti (1999a, 18–19) and Magarshack (1950, 25, 33–34). He would disguise himself as a tramp or drunk and visit the railway station, or as a fortune-telling gypsy. As Benedetti explains, however, Stanislavski soon abandoned the technique of maintaining a characterisation in real life; it does not form a part of his "system".

^ Skog (2010, 16).

^ Gussow (1982).

^ Abramson (2015, 135).

^ Flom (2009, 241).

^ French (2008).

^ Hamilton, Alan (17 May 1982). "The Times Profile: Laurence Olivier at Seventy-Five". The Times. p. 8.The American actor Dustin Hoffman, playing a victim of imprisonment and torture in the film The Marathon Man, prepared himself for his role by keeping himself awake for two days and nights. He arrived at the studio disheveled and drawn to be met by his co-star, Laurence Olivier. "Dear boy, you look absolutely awful," exclaimed the First Lord of the Theatre. "Why don't you try acting? It's so much easier." Never was a grosser untruth spoken in jest. Laurence Kerr Olivier . . . would be the last man on earth to regard his chosen profession as easy.

.mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Before Brando, There Was Dilip Kumar, The Quint, December 11, 2015

^ "'Even actors of today have influences of Dilip Kumar'". Rediff. 11 November 2012.

^ Kumar, Dilip (2014). Dilip Kumar: The Substance and the Shadow. Hay House. p. 12. ISBN 9789381398968.

^ "Unmatched innings". The Hindu. 24 January 2012. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 9 January 2015.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

^ Hamden, Raymond. “Clinical and Forensic Psychology.”

^ Grandey, Alicia A. “When ‘The Show Must Go On’: Surface Acting As Determinants of Emotional Exhaustion and Peer-Rated Service Delivery.”

^ Grandey, Alicia A. “When ‘The Show Must Go On’: Surface Acting As Determinants of Emotional Exhaustion and Peer-Rated Service Delivery.”

^ Judge, Timothy A. “Is Emotional Labor More Difficult for Some than for Others? A Multi-level, Experience-sampling Study.”

^ Hamden, Raymond. “Clinical and Forensic Psychology.”

^ Konin, Elly A. “Acting Emotions: Shaping Emotions on Stage.”

^ Method Acting: Method or Madness?

^ Warren Beatty went full method by directing Rules Don’t Apply as Howard Hughes

^ Method To The Madness: 3 Actors That Took Method Acting To The Next Level

^ Extreme weight loss and tooth extraction: when method acting goes too far

^ Getting Schooled on ‘Caginess’ by a Nicolas Cage Expert

^ Michael Caine 'uses painful secret to cry on set'

^ The Documentary That Reveals Just How Method Jim Carrey Went to Play Andy Kaufman

^ Montgomery Clift: The Original Method Actor

^ Method Acting: Method or Madness?

^ Remembering James Dean: From Method Actor to Screen Idol

^ The Method Acting of Robert De Niro

^ Johnny Depp - There's method in his madness

^ Extreme weight loss and tooth extraction: when method acting goes too far

^ ‘If you talk to anyone on set they don’t take me seriously at all – much to my dismay’

^ Sally Field Just As Method As Daniel Day-Lewis, She Says

^ Method Actor James Franco Stayed in Character as Tommy Wiseau, and Seth Rogen Couldn't Handle It

^ The 10 Best Ed Harris Movie Performances

^ Method acting can go too far – just ask Dustin Hoffman

^ Acting advice from Angelina Jolie - StandBy Method Acting Studio

^ Extreme weight loss and tooth extraction: when method acting goes too far

^ Tom Hardy Understands Shia LaBeouf’s Extreme Method Acting: ‘Drama Is Not Known to Attract Stable Types’

^ Method Acting: Method or Madness?

^ 9 Times Jared Leto Went Full Method for a Role

^ METHOD ACTING IS NOT ABOUT LOSING YOURSELF IN A CHARACTER

^ Case Study: Jack Nicholson’s Method Acting

^ Edward Norton On Why Method Acting Is Misunderstood — Hamptons Film Festival

^ HARRY POTTER AND THE SCARY GARY OLDMAN METHOD ACTING LESSON

^ Al Pacino demonstrates the magic of Method acting in the 'naturalistic fairy tale' Manglehorn

^ Method Acting: 5 Actors Who Turned It Into an Art Form

^ Is Method Acting Destroying Actors?

^ METHOD ACTING IS NOT ABOUT LOSING YOURSELF IN A CHARACTER

^ The Man Who Never Was: The Paradoxes and Genius of Peter Sellers

^ The Method gone bananas? How motion capture actors are embracing their inner ape

^ Extreme weight loss and tooth extraction: when method acting goes too far

^ Michelle Williams: I was born to play Marilyn

Sources

Primary sources

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Adler, Stella. 2000. The Art of Acting. Ed. Howard Kissel. New York: Applause.

ISBN 978-1-55783-373-0.

Adler, Stella. 1990. The Technique of Acting. New York: Bantam.

ISBN 978-0-553-34932-0.

Hagen, Uta and Haskel Frankel. 1973. Respect for Acting. New York: Macmillan.

ISBN 0-02-547390-5.

Hagen, Uta. 1991. A Challenge for the Actor. New York: Scribner.

ISBN 0-684-19040-0.

Meisner, Sanford, and Dennis Longwell. 1987. Sanford Meisner on Acting. New York: Vintage.

ISBN 978-0-394-75059-0.

Stanislavski, Konstantin. 1936. An Actor Prepares. London: Methuen, 1988.

ISBN 0-413-46190-4.

Stanislavski, Konstantin. 1938. An Actor's Work: A Student's Diary. Trans. and ed. Jean Benedetti. London and New York: Routledge, 2008.

ISBN 0-415-42223-X.

Stanislavski, Konstantin. 1957. An Actor's Work on a Role. Trans. and ed. Jean Benedetti. London and New York: Routledge, 2010.

ISBN 0-415-46129-4.

Strasberg, Lee. 1965. Strasberg at the Actors Studio: Tape-Recorded Sessions. Ed. Robert H. Hethmon. New York: Theater Communications Group.

Strasberg, Lee. 1987. A Dream of Passion: The Development of the Method. Ed. Evangeline Morphos. New York: Plume, 1988.

ISBN 978-0-452-26198-3.

Strasberg, Lee. 2010. The Lee Strasberg Notes. Ed. Lola Cohen. London: Routledge.

ISBN 978-0-415-55186-1.

Secondary sources

- Abramson, Leslie H. 2015. Hitchcock and the Anxiety of Authorship.. New York: Palgrave.

ISBN 978-1-137-30970-9. - Banham, Martin, ed. 1998. The Cambridge Guide to Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

ISBN 0-521-43437-8. - Benedetti, Jean. 1989. Stanislavski: An Introduction. Revised edition. Original edition published in 1982. London: Methuen.

ISBN 0-413-50030-6. - Benedetti, Jean. 1998. Stanislavski and the Actor. London: Methuen.

ISBN 0-413-71160-9. - Benedetti, Jean. 1999a. Stanislavski: His Life and Art. Revised edition. Original edition published in 1988. London: Methuen.

ISBN 0-413-52520-1. - Benedetti, Jean. 1999b. "Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theatre, 1898–1938". In Leach and Borovsky (1999, 254–277).

- Blum, Richard A. 1984. American Film Acting: The Stanislavski Heritage. Studies in Cinema 28. Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Press.

- Braun, Edward. 1982. "Stanislavsky and Chekhov". The Director and the Stage: From Naturalism to Grotowski. London: Methuen.

ISBN 0-413-46300-1. p. 59–76. - Carnicke, Sharon M. 1998. Stanislavsky in Focus. Russian Theatre Archive Ser. London: Harwood Academic Publishers.

ISBN 90-5755-070-9. - Carnicke, Sharon M. 2000. "Stanislavsky's System: Pathways for the Actor". In Hodge (2000, 11–36).

- Carnicke, Sharon M. 2009. Stanislavsky in Focus: An Acting Master for the Twenty-First Century. 2nd ed. of Carnicke (1998). Routledge Theatre Classics. London: Routledge.

ISBN 978-0-415-77497-0. - Counsell, Colin. 1996. Signs of Performance: An Introduction to Twentieth-Century Theatre. London and New York: Routledge.

ISBN 0-415-10643-5. - Daily Telegraph, The. 2013. "The Method Madness of Daniel Day-Lewis". The Daily Telegraph 23 January 2013. Web. Accessed 13 August 2016.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. 2013. "Stella Adler (American Actress)". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Web. 27 October 2011.

- Flom, Eric L. 2009. Silent Film Stars on the Stages of Seattle: A History of Performances by Hollywood Notables. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

ISBN 978-0-7864-3908-9. - French, Philip. 2008. "Philip French's Screen Legends: Charles Laughton". The Guardian. 21 September 2008. Web. Accessed 31 August 2016.

- Gallagher-Ross, Jacob. 2018. "Theaters of the Everyday". Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

ISBN 978-0810136663. - Golub, Spencer. 1998. "Stanislavsky, Konstantin (Sergeevich)". In Banham (1998, 1032–1033).

- Gordon, Marc. 2000. "Salvaging Strasberg at the Fin de Siècle". In Krasner (2000, 43–60).

- Gordon, Robert. 2006. The Purpose of Playing: Modern Acting Theories in Perspective. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P.

ISBN 0-472-06887-3. - Gussow, Mel. 1982. "Obituary: Lee Strasberg of Actors Studio Dead". The New York Times 18 February 1982. Web. Accessed 4 March 2014.

- Hayward, Susan. 1996. Key Concepts in Cinema Studies. Key Concepts ser. London: Routledge.

ISBN 978-0-415-10719-8. - Hodge, Alison, ed. 2000. Twentieth-Century Actor Training. London and New York: Routledge.

ISBN 0-415-19452-0. - Hull, S. Loraine. 1985. Strasberg's Method as Taught by Lorrie Hull. Woodbridge, CN: Ox Bow.

ISBN 0-918024-39-0. - Innes, Christopher, ed. 2000. A Sourcebook on Naturalist Theatre. London and New York: Routledge.

ISBN 0-415-15229-1. - Kase, Larina. 2011. Clients, Clients, and More Clients!: Create an Endless Stream of New Business with the Power of Psychology. New York: McGraw–Hill.

ISBN 0-07-177100-X. - Krasner, David, ed. 2000a. Method Acting Reconsidered: Theory, Practice, Future. New York: St. Martin's P.

ISBN 978-0-312-22309-0. - Krasner, David. 2000b. "Strasberg, Adler, Meisner: Method Acting". In Hodge (2000, 129–150).

- Leach, Robert. 2004. Makers of Modern Theatre: An Introduction. London: Routledge.

ISBN 0-415-31241-8. - Leach, Robert, and Victor Borovsky, eds. 1999. A History of Russian Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

ISBN 0-521-43220-0.

Lewis, Robert. 2003. Slings and Arrows: Theater in My Life. New York: Hal Leonard Corporation.

ISBN 1-55783-244-7.

Magarshack, David. 1950. Stanislavsky: A Life. London and Boston: Faber, 1986.

ISBN 0-571-13791-1.- Milling, Jane, and Graham Ley. 2001. Modern Theories of Performance: From Stanislavski to Boal. Basingstoke, Hampshire and New York: Palgrave.

ISBN 0-333-77542-2. - Roach, Joseph R. 1985. The Player's Passion: Studies in the Science of Acting. Theater:Theory/Text/Performance Ser. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P.

ISBN 0-472-08244-2. - Skog, Jason. 2010. Acting: A Practical Guide to Pursuing the Art. Mankato, MN: Compass Point.

ISBN 978-0-7565-4364-8. - Toporkov, Vasily Osipovich. 2001. Stanislavski in Rehearsal: The Final Years. Trans. Jean Benedetti. London: Methuen.

ISBN 0-413-75720-X. - Whyman, Rose. 2008. The Stanislavsky System of Acting: Legacy and Influence in Modern Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

ISBN 978-0-521-88696-3.

Comments

Post a Comment